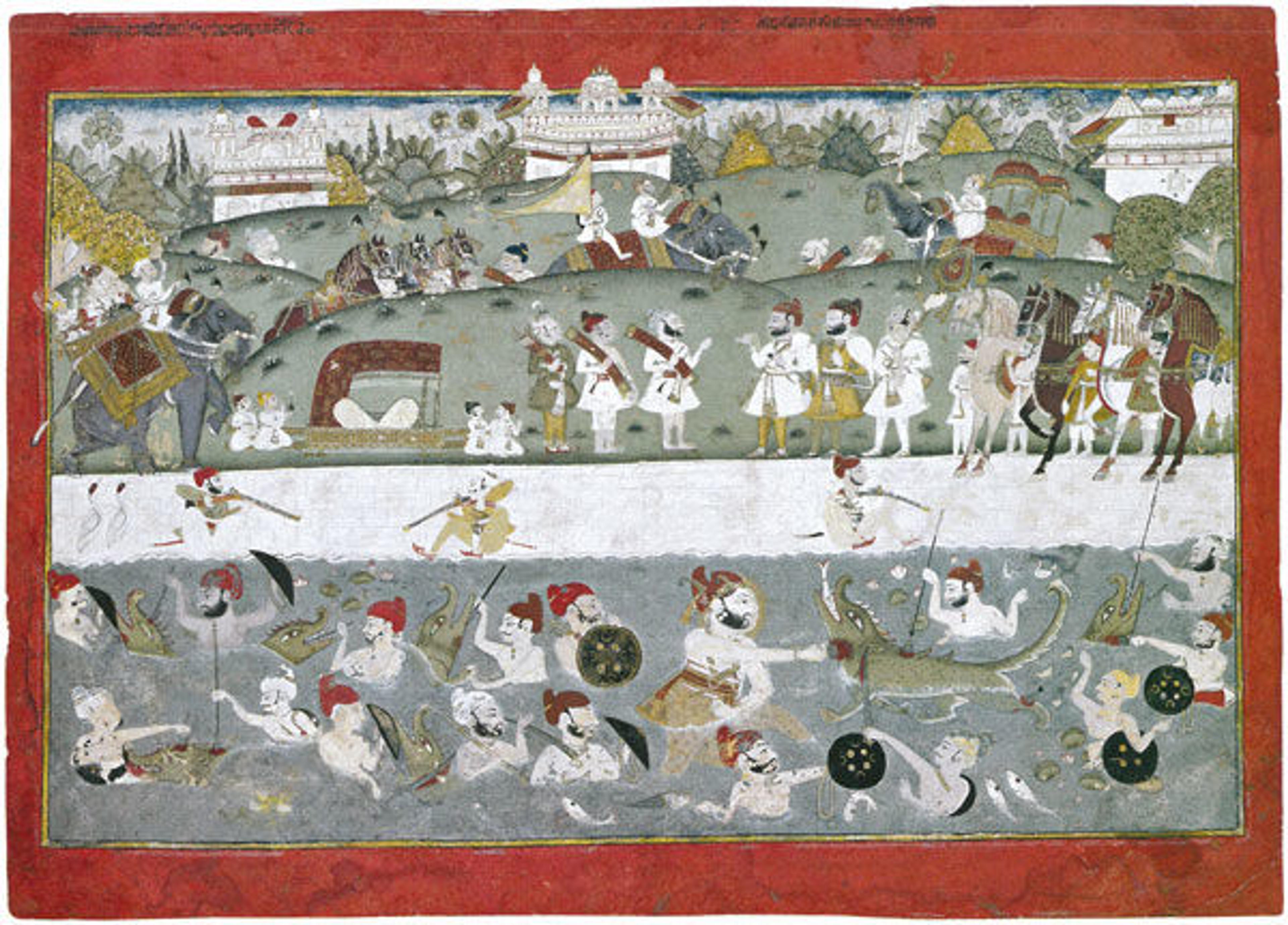

Maharaja Kumar Isri Singh's Crocodile Hunt, ca. 1760. Western India, Rajasthan, Jaipur or Unaira. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper; 16 15/16 x 23 5/8 in. (43 x 60 cm). Lent by Maximilian James Polsky

«The Royal Hunt: Courtly Pursuits in Indian Art, on view through December 8, brings together vibrant Mughal and Rajasthani paintings that depict royalty, nobility, and courtiers engaged in the dynamic yet dangerous sport of hunting. In addition to artworks from the Departments of Asian Art and Islamic Art, a group of weapons and hunting accessories loaned by the Department of Arms and Armor are also on display, which provide not only a greater understanding of the royal hunt, but also a rare opportunity to see these objects in person.»

What becomes immediately clear in this exhibition is how these hunting tools lend themselves to the concept of the royal hunt—signifying bravery, valor, and power. A prime example is the katar, a punch dagger native to the Indian subcontinent. One would grip the crossbar with a fist and thrust the blade into its prey, meaning that this weapon had to be used at very close range. Rajput royalty used the katar to hunt tigers and even crocodiles as demonstrations of their courage and martial skill.

In fact, it was a rite of passage for young princes to hunt dangerous predators in this manner. A painting in the exhibition (above) depicts ruler Maharaja Kumar Isri Singh in a pool of water, bare-chested, and in hand-to-hand combat with a crocodile. He has just plunged his katar into the creature, which has evidently been caught by surprise while eating. Well paired with this piece is a katar from Rajasthan (left) that, according to the Sanskrit inscription, celebrates its potency: ". . . this dagger, when pierced, is like the tongue of death."

Left: Dagger (Katar), 1852. India, Bundi, Rajasthan. Steel, gold; 17 1/2 x 3 9/16 in. (44.5 x 9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of George C. Stone, 1935 (36.25.912)

Although primarily used for warfare, matchlock guns became a favored weapon for hunting large and dangerous predators such as lions, bears, crocodiles, tigers, and boars. The mechanism, or "lock," allowed one to use both hands to grip the weapon while firing, and also to keep both eyes on the target. The gun was used either while on foot or propped on the ground, as some were equipped with a forked, retractable stand.

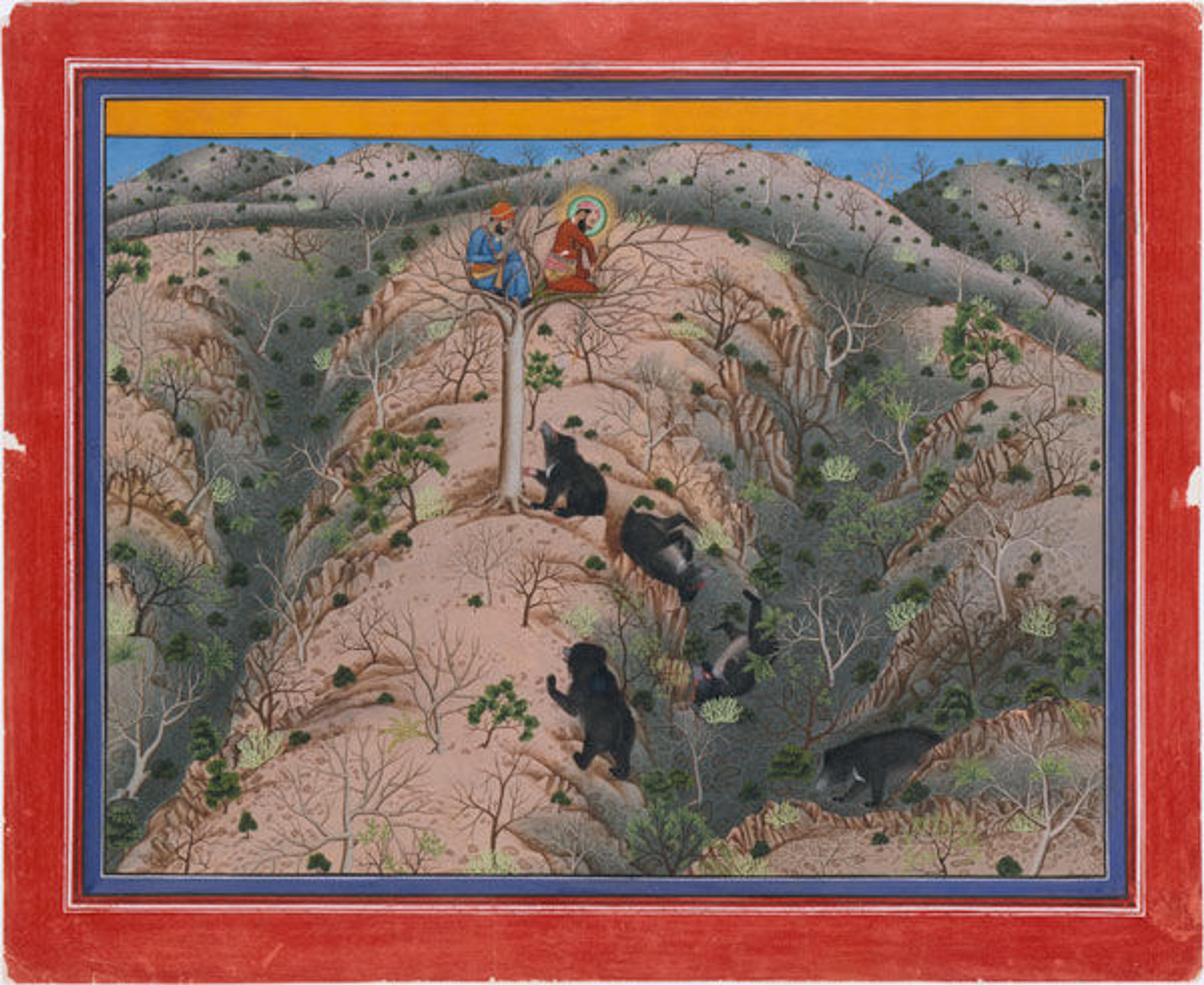

The painting below also demonstrates that the matchlock gun could be targeted at prey advantageously from treetops. It portrays Mewar ruler Maharaja Fateh Singh (r. 1884–1930) with a green-and-gold nimbus (signifying his royal status), concealed in a tree with a fellow huntsman after having just fired a backward and downward shot at a female bear from point-blank range. An interesting feature of this painting is the continuous narrative, as the animal is shown five times: the first two instances depict the bear being lured out of the ravine and moving towards the tree, perhaps due to the scent of bait; she is then shown meeting her demise; and the final two representations show her stumbling into the ravine.

Attributed to Pannalai. Maharaja Fateh Singh Hunting Female Bears, dated 1917. Western India, Rajasthan, Udaipur. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper; 13 3/8 x 18 1/4 in. (34 x 46.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Cynthia Hazen Polsky Gift, 1992 (1992.7.1)

Just as distinct as this image is one of the matchlock guns on display. Created in Rajasthan, most likely in the eighteenth century, this weapon (below) is fittingly decorated with scenes of hunting and animals, detailed with gold against a white ground. It has a square-shaped muzzle and, remarkably, also has a square-shaped barrel.

Matchlock gun (with two detail views), probably 18th century. Rajasthan, India. Steel, wood, gold, lacquer; 61 3/4 in. (156.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of George C. Stone, 1935 (32.25.2153)

This exhibition also reveals that animals were used as "living weapons" during royal hunting expeditions. For example, the Mughal emperors Akbar (r. 1556–1605) and Shah Jahan (r. 1627–1658) trained cheetahs to stalk and hunt quick-footed prey such as deer and gazelles. Smart and powerful, elephants were also used for these expeditions, with mahouts (elephant drivers) using an ankus, or elephant goad, to guide the animal into behaving or moving in a certain way. The example on view (right) has a steel blade appropriately carved with fantastical creatures. The brass butt is formed in the shape of a doglike creature leaping from the mouth of a tiger.

Right: Elephant goad (Ankus), 17th century. South India. Steel, brass; 16 in. (40.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of George C. Stone, 1935 (32.25.1868)

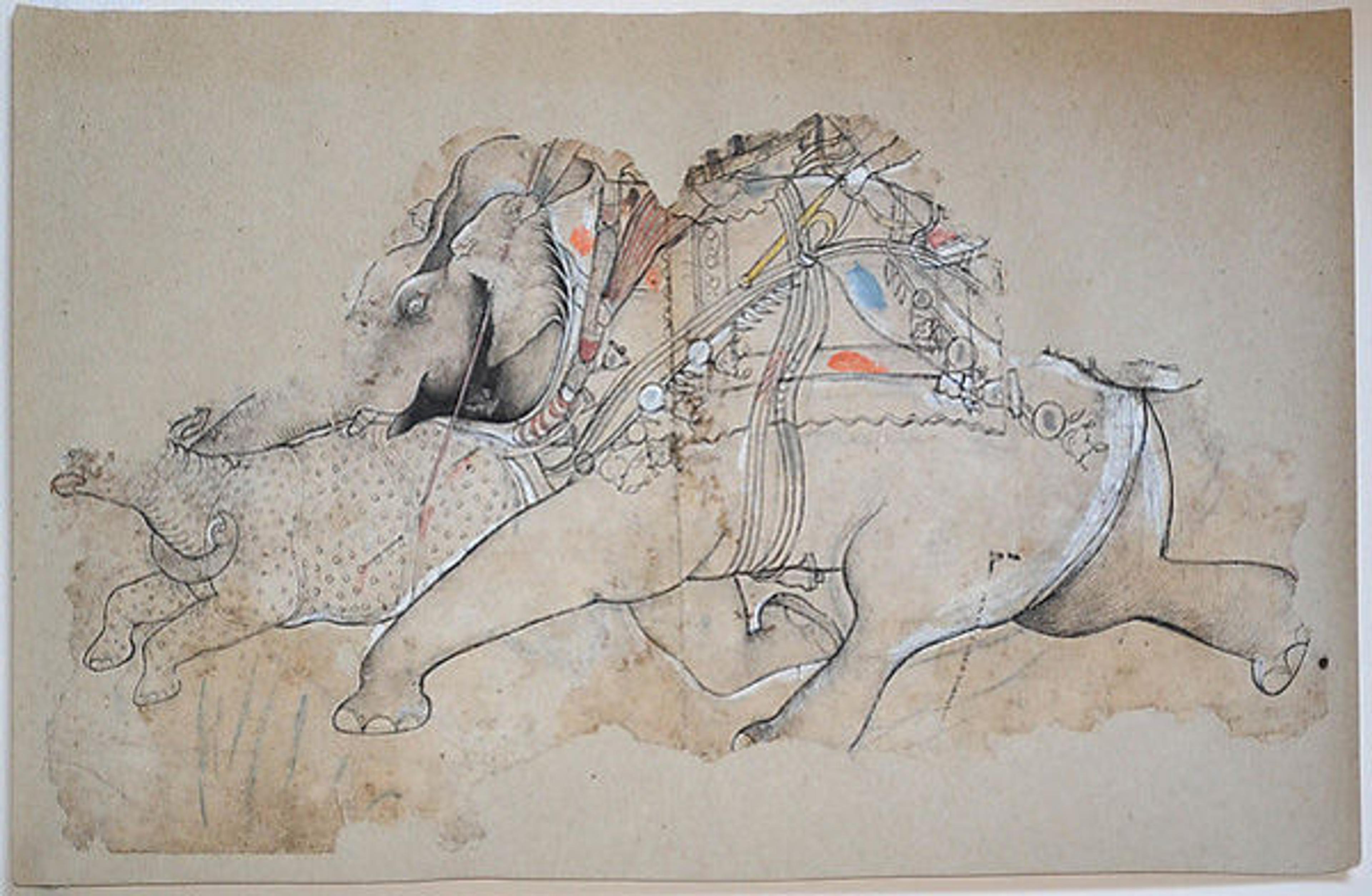

Although this particular piece might have been used for ceremonial processions, a drawing nearby in the exhibition (below) shows a gold ankus tucked into the elephant's harness. The useful tool remains untouched in this extraordinary study, as the elephant is clearly in complete control of securing the kill of a fleeing rhinoceros. The elephant's eyes are focused with concentration as its trunk wraps around the target's neck, its might and power further emphasized by the swinging bells attached to the trappings.

Attributed to The Kota Master (Indian, active early 18th century). Study for Rao Ram Singh I Hunting Rhinoceros on an Elephant, ca. 1690–1700. Western India, Rajasthan, Kota. Ink with touches of color over charcoal underdrawing on paper; 10 1/2 x 19 7/8 in. (26.7 x 50.5 cm). Lent by Terence McInerney

The weapons and hunting devices on display in the exhibition not only complement the works on paper, but also, in conjunction with them, bring the spectacle and sport of the royal hunt in India to life, a subject that has been celebrated throughout the history of South Asian art.

Related Links

The Royal Hunt: Courtly Pursuits in Indian Art, on view June 20–December 8, 2015

View all blog posts related to the Department of Arms and Armor.