![Liturgical cuffs (epimanikion), 1740. Greek. Silk, metal thread, and metal wire embroidery on a foundation of silk satin; 9 3/4 x 5 3/4 in. (24.8 x 14.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of George Blumenthal, 1941 (41.100.235 [top], 41.100.234 [bottom])](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/cctd4ker/production/9cf0f3f818988161c2b1d81c843e3014706a46fc-600x734.jpg?w=3840&q=75&fit=clip&auto=format)

Liturgical cuffs (epimanikia), 1740. Greek. Silk, metal thread, and metal wire embroidery on a foundation of silk satin; 9 3/4 x 5 3/4 in. (24.8 x 14.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of George Blumenthal, 1941 (41.100.235 [top], 41.100.234 [bottom])

«One of the most striking aspects of the silk and metal-thread embroideries on view through November 1, 2015, in Liturgical Textiles of the Post-Byzantine World is how labor-intensive they are. One might wonder who devoted so much time and eyestrain to creating these pieces, and at whose behest? Although they form a minority within the body of surviving liturgical embroideries, pieces inscribed with the names of the donor or the embroiderer help scholars to answer these questions.»

Left: Chalice cover, late 15th century. Georgian, Abkhasia. Silk and metal-thread embroidery on a foundation of silk satin backed with linen plain weave; 16 3/4 x 17 in. (42.5 x 43.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.128)

Inscriptions help provide a date for some of the earliest and latest pieces found in the exhibition. The Georgian inscriptions on a chalice cover plead for the salvation of Solomon Shavrashidze (or Sharvashidze), a Georgian noble who also donated, in 1495, a silver-bound book of the Gospels to the church at Pitsunda/Bichvinta, located on the Abkhazian Black Sea coast of Georgia. Another embroidery on view, a pair of liturgical cuffs, or epimanikia, depicting the Annunciation, bears an inscription in Greek characters that spans the two cuffs. Although it is marked by a number of misspellings, one can decipher the name of the embroiderer, one Doulisa Tzoeris, who dedicated the epimanikia in memory of her son and of her parents. The characters at the end of the inscription give the date of 1740.

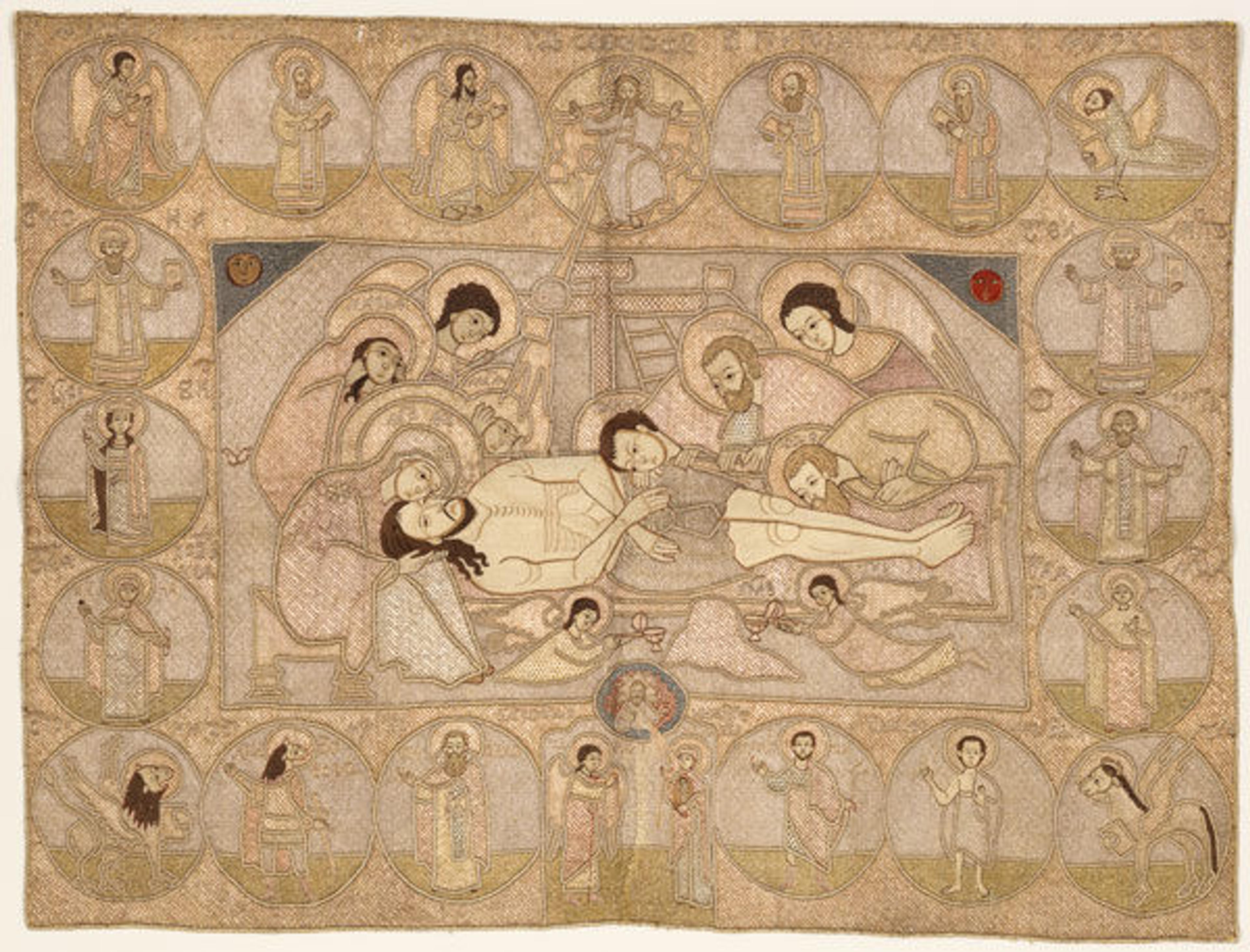

In a third instance, that of a Russian liturgical veil, or epitaphios, the art-historical tools of stylistic comparison and iconographic analysis allow us to infer the history of the object's creation even in the absence of a dedicatory inscription.

Epitaphios (Plashchanitsa), third quarter 17th century. Russian, Moscow or environs. Silk and metal-thread embroidery on a foundation of linen plain weave; 24 1/4 x 32 in. (61.6 x 81.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Stephan Rosenak, 1946 (46.191)

The choice of central image—the epitaphios thrēnos, or lamentation over Christ's lifeless body after his crucifixion—is standard for this type of textile. In fact, the composition of this scene, as with similar embroidered veils of this period, is lifted in more or less direct fashion from famous epitaphioi of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The Slavonic inscriptions, combined with the insistent geometric patterning of the embroidery, help to place this example in seventeenth-century Russia. The depiction of Saint John the Baptist with wings (as the "angel," that is, the harbinger of Christ's appearing) is an iconographic detail favored in Russia, although it occasionally appears elsewhere in late Byzantine and post-Byzantine contexts.

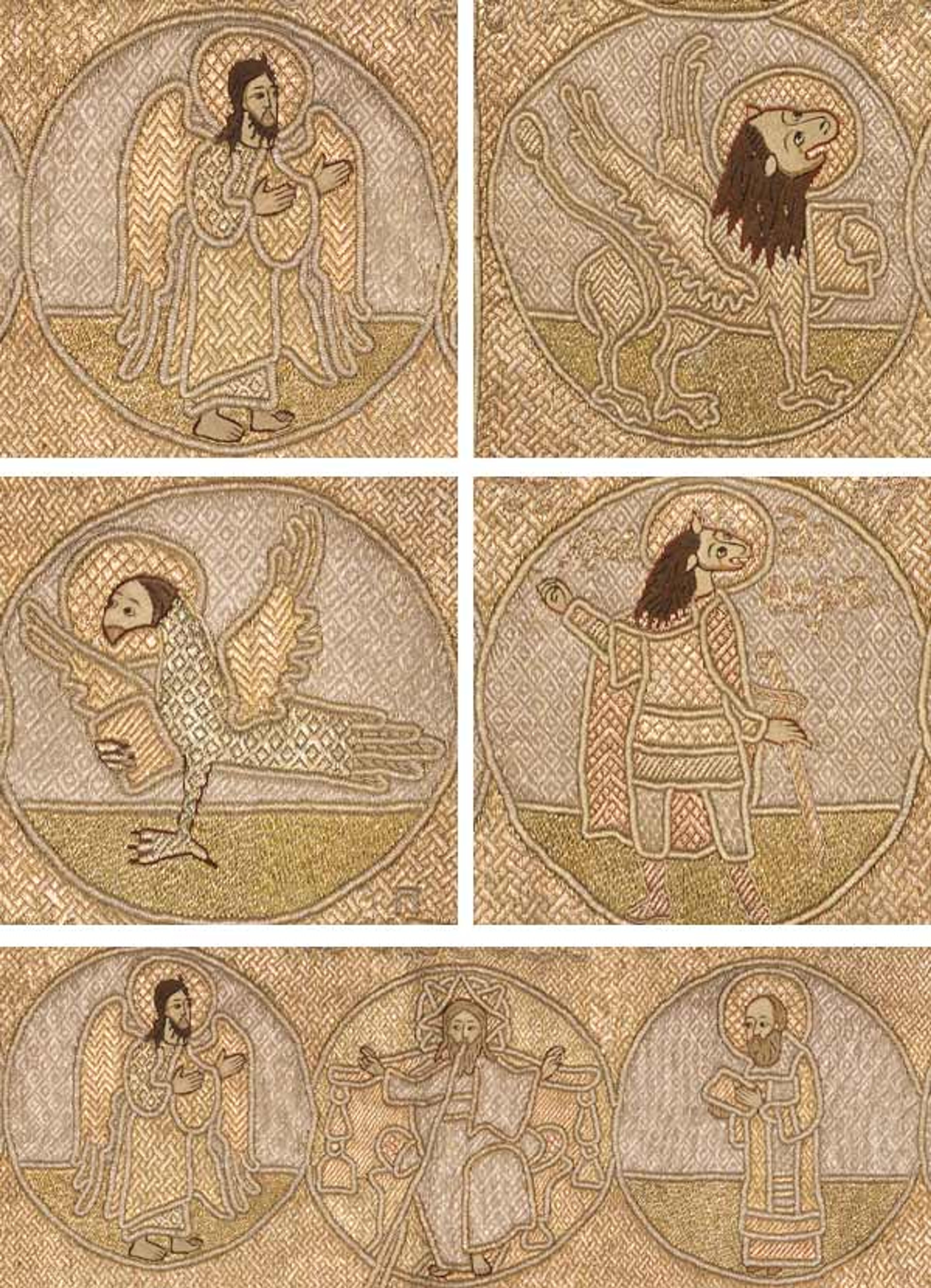

Detail views of 46.191, depicting (clockwise from top left): Saint John the Baptist, the symbol of the Evangelist John, Saint Christopher, the Lord of Hosts between Saints John the Baptist and Gregory, and the symbol of the Evangelist Mark

Another detail that points to Russia is the correlation of the four Evangelist symbols found in the corners to the four Gospel writers. Most Byzantine and post-Byzantine embroideries follow the system familiar also in the Latin West: the angel represents Matthew; the winged lion Mark; the winged ox Luke; and the eagle John, as is also shown on another roundel in the exhibition. Here, however, as in many Russian works of art, the winged lion is labeled "Saint John" and the eagle "Saint Mark." (The other zoomorphic figure, second from left in the bottom row, is Saint Christopher, who, according to some medieval versions of his legend, was a member of the Cynocephali, that is, a race of dog-headed people supposedly residing in North Africa.)

At the center of the top of the veil is the depiction of the Lord of Hosts, labeled Gospod' Savaof (Lord of Sabaoth); in the same position on the lower border is the Annunciation, with a small image of God the Father sending the Holy Spirit upon the womb of the Virgin Mary to effect the conception of Christ. The corners, as already mentioned, contain the symbols of the four Gospels, while the remaining fourteen roundels are occupied with figures of saints.

Detail views of 46.191, depicting the Annunciation (left) and Tsarevich Dmitrii Ivanovich (right)

Fully half of these represent individuals closely associated with the Orthodox Church in Muscovy in the fourteenth through sixteenth centuries. These include the important monastic founders Saint Sergius of Radonezh and Saint Cyril of Beloozero, both active in the fourteenth century; the Moscow Metropolitans Peter (†1326), Alexius (†1378), Jonas (†1461), and Philip II (†1568); and the holy Tsarevich—Dmitrii Ivanovich—the son of Ivan the Terrible who was killed under mysterious circumstances in 1591. The remaining saints include John the Baptist, Anna the Prophetess, Procopius, John the Hermit, Pelagia of Tarsus, Gregory, and Christopher.

The sainted Tsarevich Dmitrii was popularly regarded as a martyr to the machinations of Boris Godunov, and he enjoyed a thriving cult following the translation of his remains to Moscow, in 1606. Tsar Michael I Romanov (r. 1613–1645) and his son Alexei Mikhailovich (r. 1645–1676) both used the cult of the Tsarevich Dmitrii as a tool to legitimate their reign. His imagery was particularly propagated by the workshops of the Stroganov family, which was based in the city of Solvychegodsk, near Arkhangelsk in the Russian far north.

With their vast fortune built on salt making, the Stroganovs provided financial and military backing to the tsars in Moscow from the time of Ivan the Terrible (r. 1547–1584) onward. Embroiderers working under the patronage of Dmitrii Andreevich Stroganov (ca. 1622–1670) produced several hangings with images of the Tsarevich Dmitrii and his supposed martyrdom. One of these pieces—now in the Historical and Art Museum of Solvychegodsk—was presented to the local Cathedral of the Annunciation in 1654. With its border of saints in roundels, it is strikingly similar in imagery and style to the Metropolitan Museum's embroidery, and even includes some of the same rather unusual saints, such as John the Hermit and the animal-headed Saint Christopher.

In the 1650s and 1660s, the Stroganovs were giving embroidered works not only to the churches of their own region, but also to the major churches and monasteries of Moscow and its environs. Some of these textile gifts were inscribed with the names of Dmitrii's son, Grigorii, and his daughter, Pelageia—names that, with that of his wife, Anna, are echoed by the names of the saints featured on the border of the Museum's veil.

Detail views of 46.191, depicting Anna the Prophetess (left), and Metropolitan Philip II of Moscow (right)

The selection of saints in the roundels may help us to further pinpoint the date and circumstances for which this textile was embroidered. The depictions of Saints Pelagia, Anna, and Gregory all relate to members of Dmitrii Andreevich Stroganov's immediate family, and symbolically associate them with the sainted leaders of the Russian Orthodox Church. The canonization of Metropolitan Philip II of Moscow, in 1652, gives the earliest possible date (terminus post quem) for the embroidery—one that fits quite closely with the stylistically comparable examples from the Stroganov workshops.

One final detail may help further narrow the date: the placement of Saint Gregory in the upper border of the epitaphios, immediately to the left of God the Father. His appearance in this place of honor, opposite the winged figure of John the Baptist, likely indicates that the piece was embroidered for a church or monastery dedicated to Saint Gregory. A likely candidate is the Church of Saint Gregory of Neocaesarea in the Zamoskvorech'e region of Moscow. The monumental rebuilding on the site of an earlier wooden church was commissioned by Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich, and work was begun in 1662.

Left: Karp Guba and Ivan Kuznechik, architects. Church of Saint Gregory of Neocaesarea, Moscow, built 1662 and following. Photo courtesy of Alexei Lidov

In 1671, the new church served as the setting for the tsar's marriage to his second wife, Natalia Naryshkina, the mother of the future Peter the Great. Given the Stroganov's demonstrated interest in supporting the early members of the Romanov dynasty, it would hardly be surprising for them to give a donation to an important new church commissioned by the tsar, particularly one dedicated to the name-saint of Grigorii Dmitrievich Stroganov.

Art historians can use both explicit inscriptions and the implicit evidence of style and iconography to trace liturgical embroideries back to the churches that used them, the patrons that sponsored them, and embroiderers that created them. Not only does this information provide us with important milestones for the attribution and dating of similar pieces, but it also helps us to reconstruct the networks of ties, both social and sacred, created and reinforced through the delicate threads of embroidery.

The author would like to thank Professor Michael Flier of Harvard University for his helpful bibliographical references on the churches of Moscow.

Related Links

Liturgical Textiles of the Post-Byzantine World, on view August 3–November 1, 2015

Now at the Met: "Why Vestments? An Introduction to Liturgical Textiles of the Post-Byzantine World" (August 3, 2015)

Additional Reading

Avalishvili, Z. "A Fifteenth-Century Georgian Needle Painting in the Metropolitan Museum, New York." In Georgica: A Journal of Georgian and Caucasian Studies 1.1 (October 1935): 67–74.

Chatzedake, Eugenia. Εκκλησιαστικά Κεντήματα. Athens: Benaki Museum, 1953.

Grierson, Roderick, ed. Gates of Mystery: The Art of Holy Russia. Fort Worth, TX: InterCultura, 1992.

Makarevich, Gleb V., et al., eds. Pamiatniki arkhitektury Moskvy. Zamoskvorech'e. Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1994.

Schilb, Henry. "Singing, Crying, Shouting, and Saying: Embroidered Aëres and Epitaphioi and the Sounds of the Byzantine Liturgy." In Resounding Images: Medieval Intersections of Art, Music, and Sound, edited by Susan Boynton and Diane J. Reilly, 167–187. Turnhout: Brepols, 2015.

Silkin, A. V. Stroganovskoe litsevoe shit'ë. Moscow: Progress-Traditsiia, 2002.

Smirnova, Englina, ed. Tserkovnoe shit'ë v drevnei Rusi. Moscow: Galart, 2010.