Fig. 1. Vajrabhairava with His Consort Vajravetali, 18th–19th century. Mongolia. Tung oil stucco, wood, gold, cinnabar, and other pigments; 7 1/2 x 6 in. (19.1 x 15.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Kate Read Blacque, in memory of her husband, Valentine Alexander Blacque, by exchange, 1948 (48.30.14)

«A gift to the Museum in 1949, this image of Vajrabhairava was not placed on display for many years (fig. 1). In conjunction with the work's display in the Sacred Traditions of the Himalayas exhibition, however, the Departments of Objects Conservation and Scientific Research examined this figure in order to shed light on the materials and the production technique of this unusual representation.»

This eighteenth- or nineteenth-century image of Vajrabhairava belongs to the Vajrayana pantheon of Buddhist deities. The Vajrabhairava—with his sixteen feet, thirty-four arms (thirty-two of them holding attributes), and nine heads—is a wrathful deity who shares many characteristics with Yamantaka, whose name literally means yama ("death") and antaka ("to terminate"), thus signifying the victory of wisdom over death. Here, he is shown surrounded by Tantric symbols and trampling on animals, birds, demons, and Hindu deities.

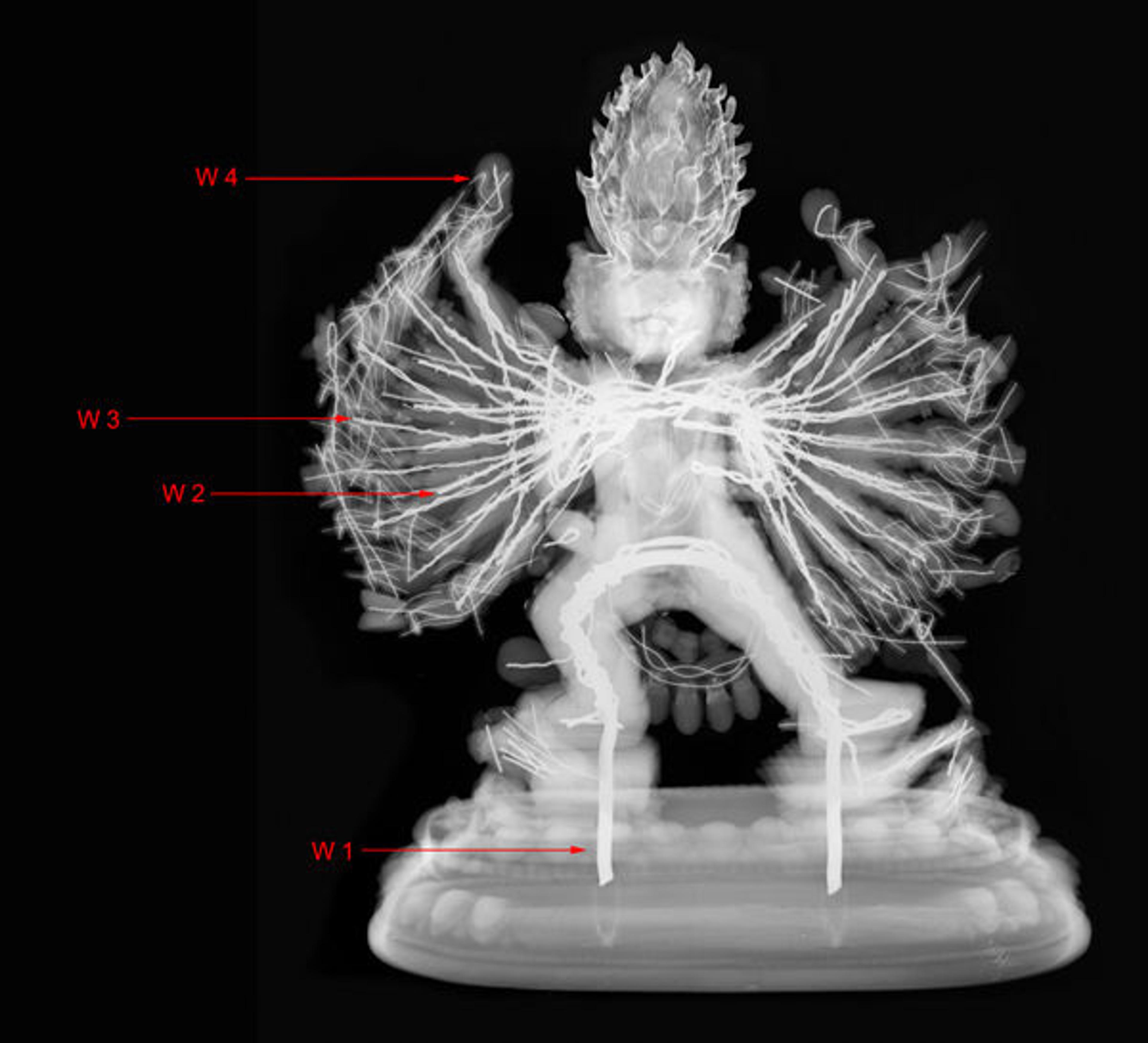

Fig. 2. X-ray radiograph of Vajrabhairava (48.30.14), with arrows indicating four different wire thicknesses

Originally the Vajrabhairava was thought to be made of gilded wood, due to its light weight and the fact that the base was carved out of wood, but closer inspection revealed that the piece is actually composed of several detachable elements. X-ray radiography revealed that the Vajrabhairava was sculpted around an elaborate metal armature in which four distinct wire thicknesses could be identified (fig. 2). While the maker chose the largest gauge wire to build an internal support structure for the body of the main figure and his consort, thinner wires were used for the arms and two sets of even finer wires for the hands and attributes.

Scientific analysis identified the material of the Vajrabhairava as a silty clay composed of different minerals and rock fragments mixed in tung oil, and copper for the metal armature. The latter is a drying substance obtained from the seeds from the nut of the tung tree (Vernicia fordii, Hemsl.), and was presumably added to increase the clay's plasticity and slow down its drying time during the modeling process.

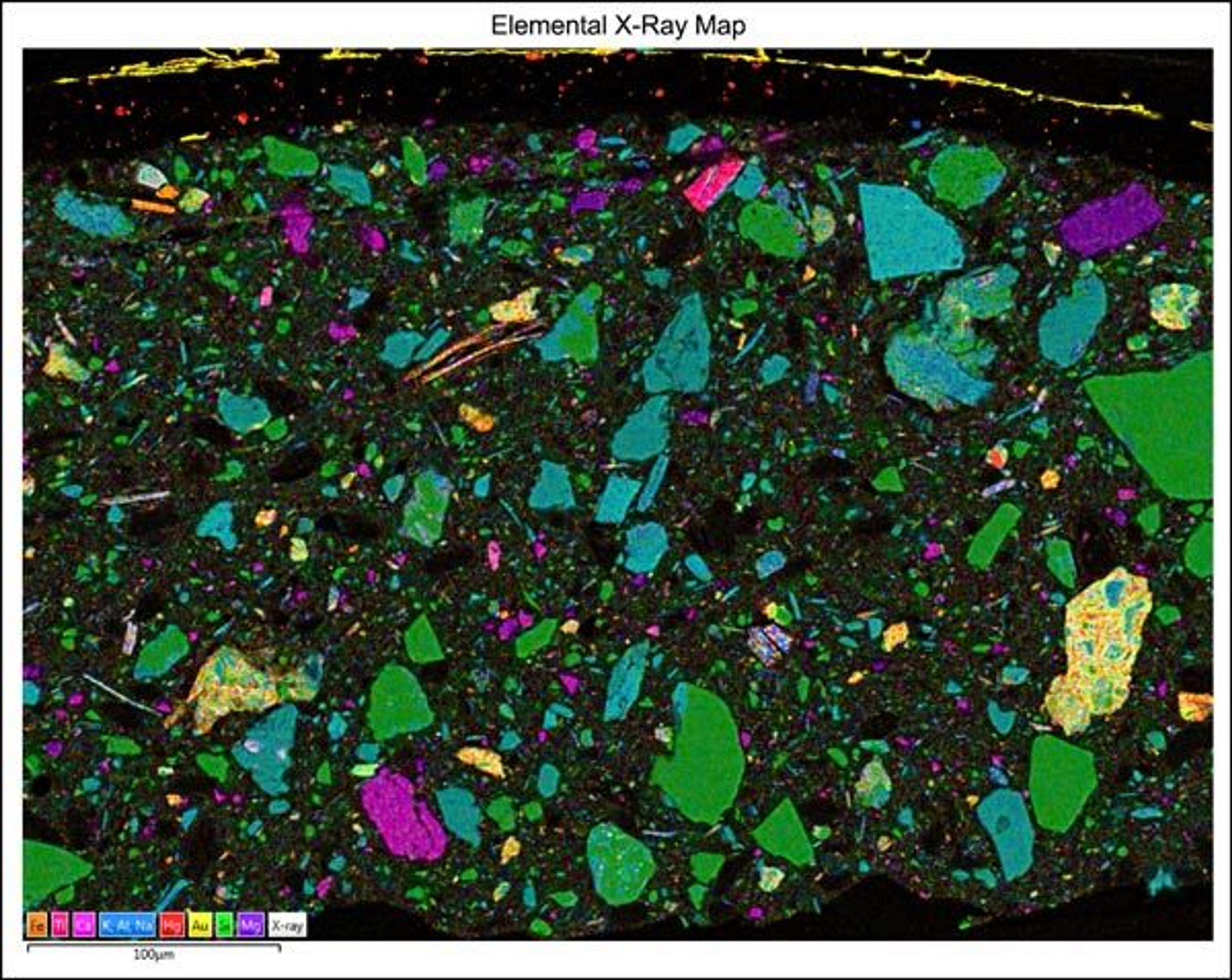

Fig. 3. A sample taken from the Vajrabhairava was examined with a scanning electron microscope (SEM). The cross section shows a layer of gold leaf (yellow line at top), a foundation layer of oil-bound cinnabar, and a matrix made of minerals and small rock fragments. The colors in the cross section represent the different elements listed in the key. SEM analysis and image by Federico Carò, Associate Research Scientist, Department of Scientific Research, MMA

Using a scanning electron microscope in the Department of Scientific Research, the elemental composition of the rock fragments present was identified and its distribution mapped (fig. 3). Further analysis focused on the composition of the elaborate surface finish of the Vajrabhairava. Pure gold leaf was adhered on top of a medium-rich, red-pigmented foundation composed of tung oil and cinnabar (figs. 4a, b)—a pigment produced when the red mineral cinnabar (mercury[II] sulfide) is ground into fine powder; the synthetic form is known as vermillion. This red foundation layer adds a warmth to the gold tone. A final coating of tung oil was then applied to protect the gold leaf surface.

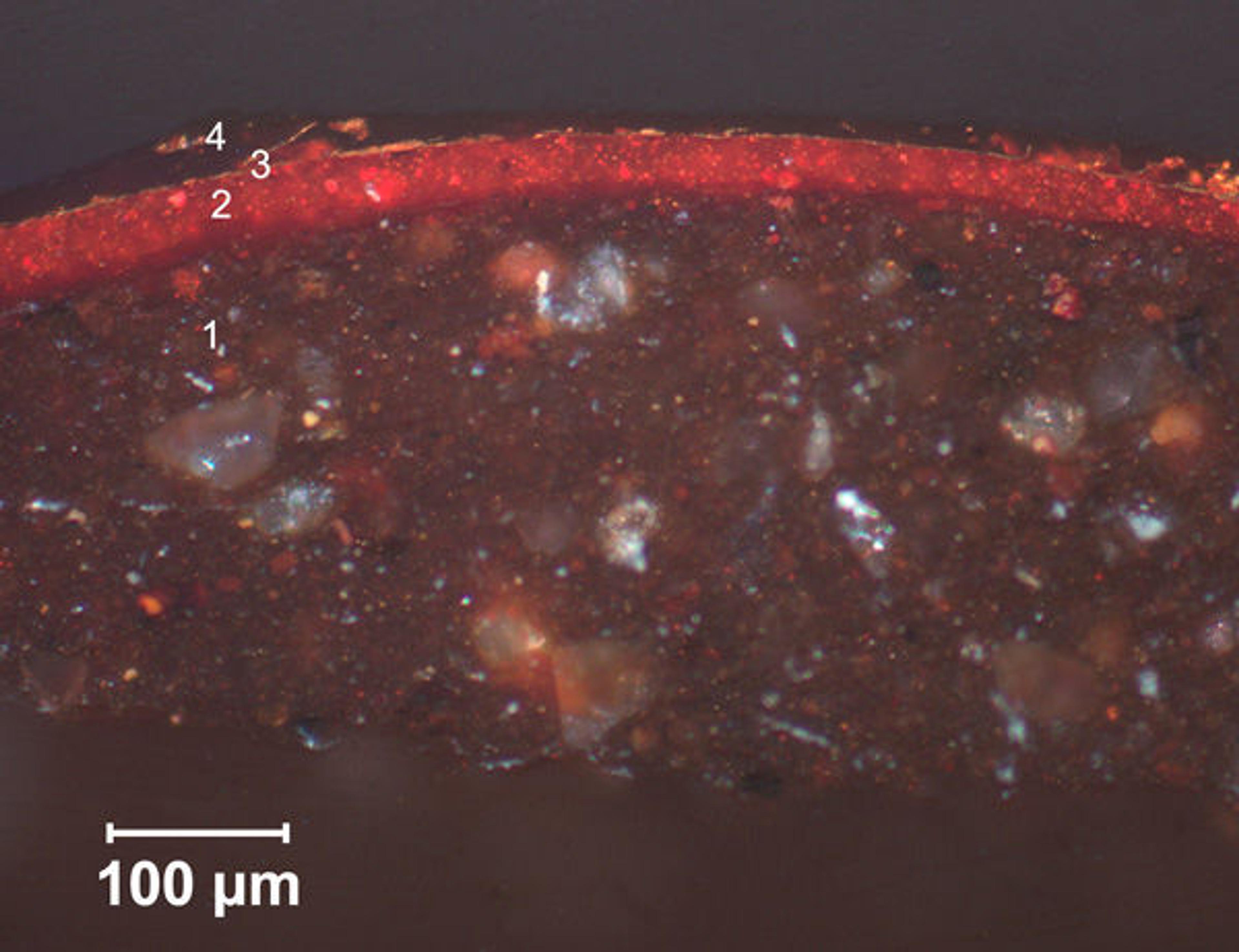

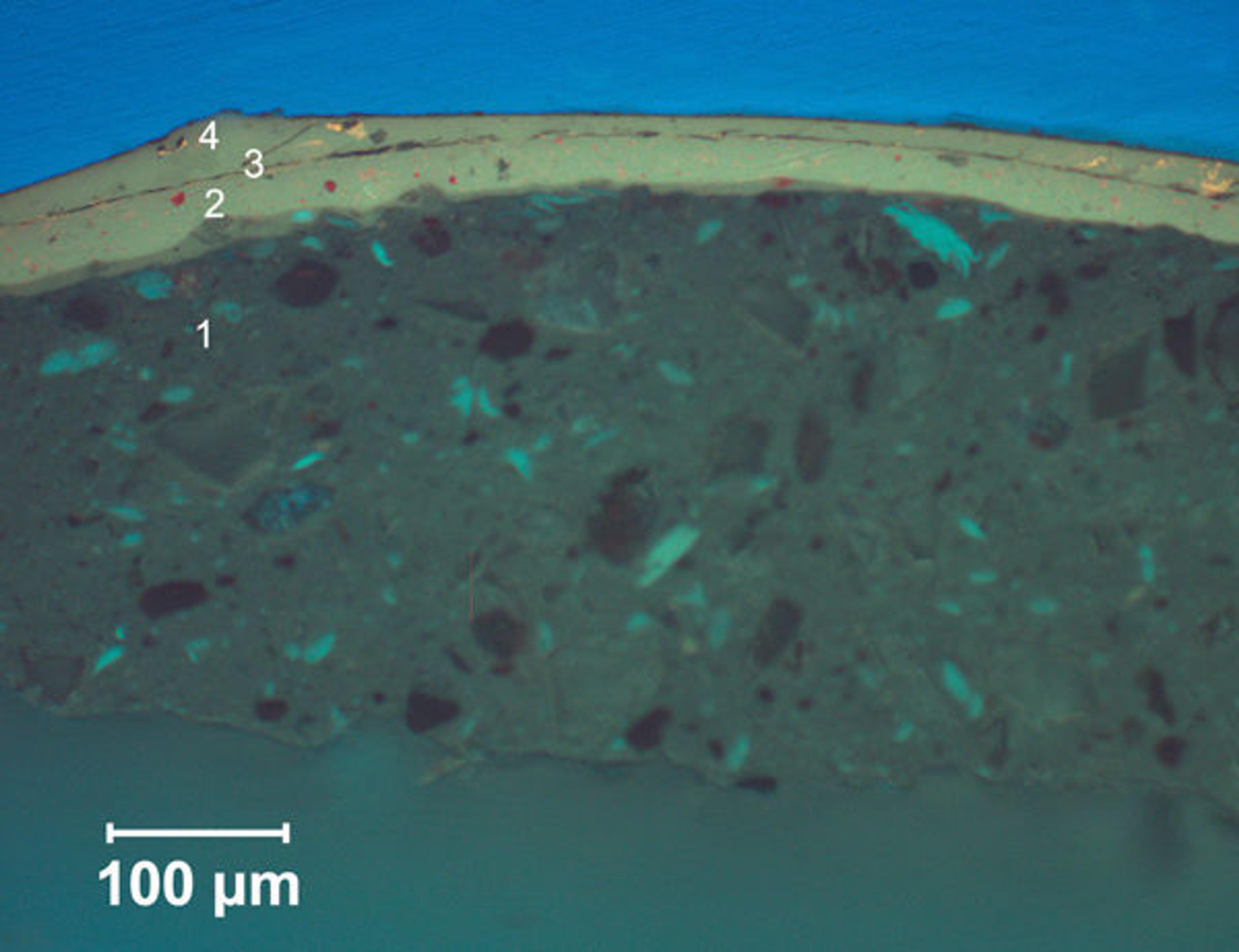

Figs. 4a (top) and 4b (bottom). Photomicrographs of a cross section, obtained from a sample taken from the base of the Vajrabhairava in regular reflected light (a) and ultraviolet light (b). The different layers of the gilding—clay matrix (1), foundation layer of oil-bound cinnabar (2), layer of gold leaf (3), and transparent top coating of tung oil (4)—become much more visible under ultraviolet light, due to the differences in fluorescence of materials such as pigments, varnishes, and gold leaf. Identification of tung oil in the different layers by Adriana Rizzo, Associate Research Scientist, Department of Scientific Research, MMA

In addition to technical examination, the Vajrabhairava underwent some conservation treatment. The figure had become brittle with age, which resulted in several losses. The image seemed to have never been repaired, and was covered in a thick layer of dust and soot (fig. 5). Based on this condition, the treatment undertaken consisted of selective cleaning using solvents with the aim of making fine features more readable, while breaks were stabilized using a mixture of synthetic resin.

Fig. 5. Detail of Vajrabhairava (48.30.14), showing a thick layer of dust and soot (dark-colored deposits)

While the sculptor of the Vajrabhairava employed a combination of manufacturing methods, we cannot say with certainty which technique was used for each separate element. The many arms, for instance, were most likely molded, since they are all virtually identical, while the thirty-two different attributes must have been separately modeled and attached. While it is entirely possible that the body was produced using molds, telltale features of this technique such as seams are not apparent. In the end, it seems clear that the sculptor of this remarkable and skillfully produced image was attempting to mimic a gilded bronze.

Fig. 6. Rear view of Vajrabhairava (48.30.14)

View all blog articles related to Sacred Traditions of the Himalayas.

Follow the conversation: #SacredTraditions

The Collaborative Fellowship Pilot Program for Indian Conservators is supported at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and SRAL by grants from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.