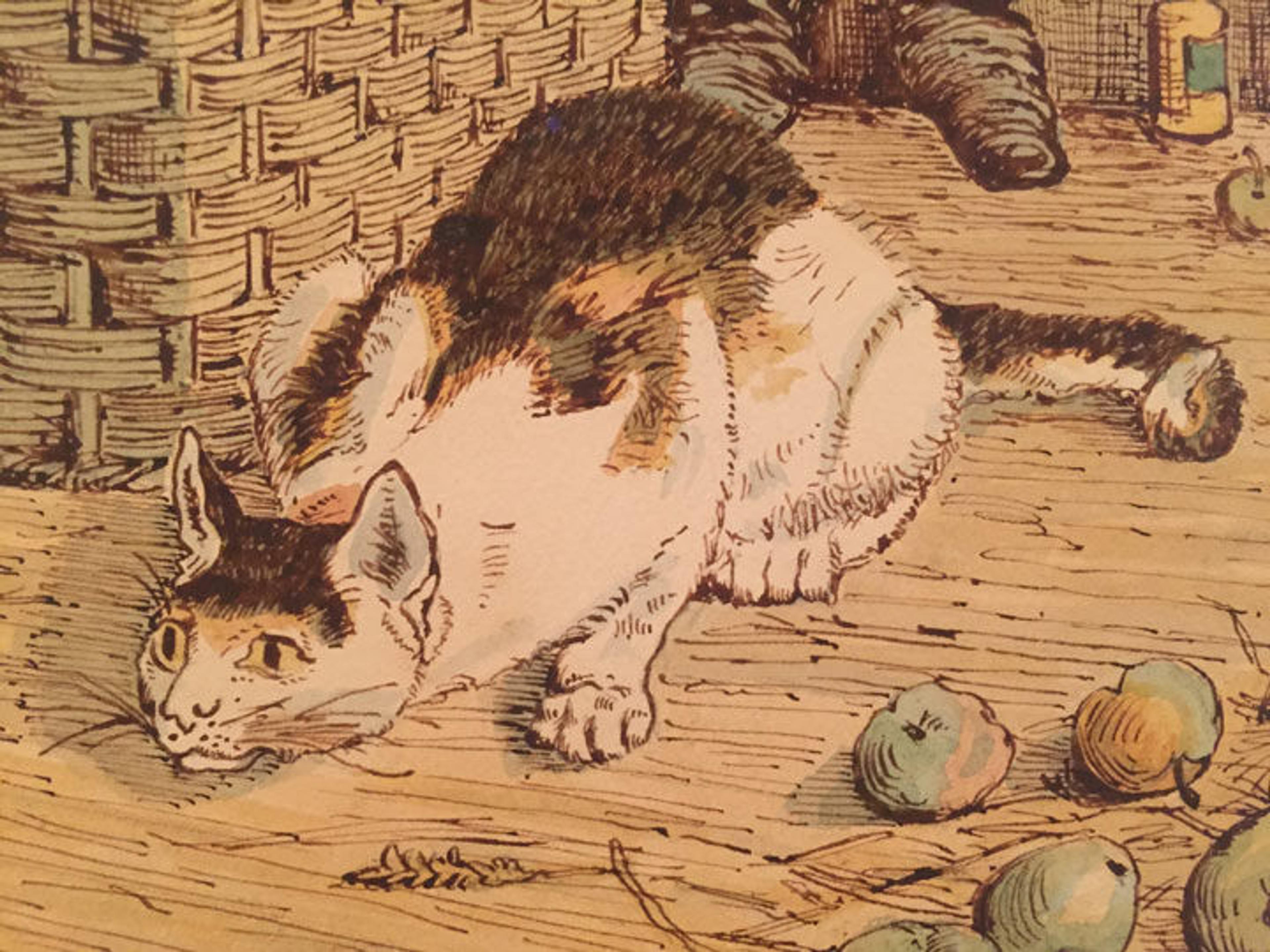

Randolph Caldecott (British, 1846–1886). The House that Jack Built, 1887. Watercolor. Private collection

«Printed works for or about children are the focus of the exhibition Printing a Child's World, on view through November 6, which features more than two dozen works from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. During the Golden Age of Illustration (1880s–1920s), artists and printers continually exchanged ideas and inspiration across media. In the world of print, publishers on both sides of the Atlantic responded to an audience that was delighted by images of whimsy, surprise, and play. The technical skill and talent of English illustrators—such as Randolph Caldecott (for whom an annual award for best children's illustration is named) and the American artists employed by the McLoughlin Brothers publishing firm—helped to further elevate the stature and popularity of children's illustration.»

British American Seymour Guy was enchanted by children's illustration, and in his painting Story of Golden Locks, he depicts a young girl reading the tale as a bedtime story. The two boys tucked into bed are spellbound and the girl's bear-shaped shadow looms behind them as a reminder of the dangers that await misbehaving children. The pages of the book fall open and we can see the image that illustrates the climax of the story, when Golden Locks jumps through a window to escape the clutches of the three bears. Guy painted a story within a story, carefully copying the illustrated prototype. But who was this other artist? This artistic inspiration?

Seymour Joseph Guy (American, 1824–1910). Story of Golden Locks, ca. 1870. Oil on canvas; 34 x 28 in. (86.4 x 71.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Daniel Wolf and Mathew Wolf, in memory of their sister, the Honorable Diane R. Wolf, 2013 (2013.604)

The wonderful thing about working in a museum is conferring with colleagues who know more than you. Curator Constance McPhee confirmed my suspicions that the image of the book was indeed a copy of one by a known illustrator. She also introduced me to the fabulous collection of children's picture books at The Met. Justin G. Schiller, a dealer in antiquarian children's books, conclusively identified the hand of British illustrator Harrison Weir.

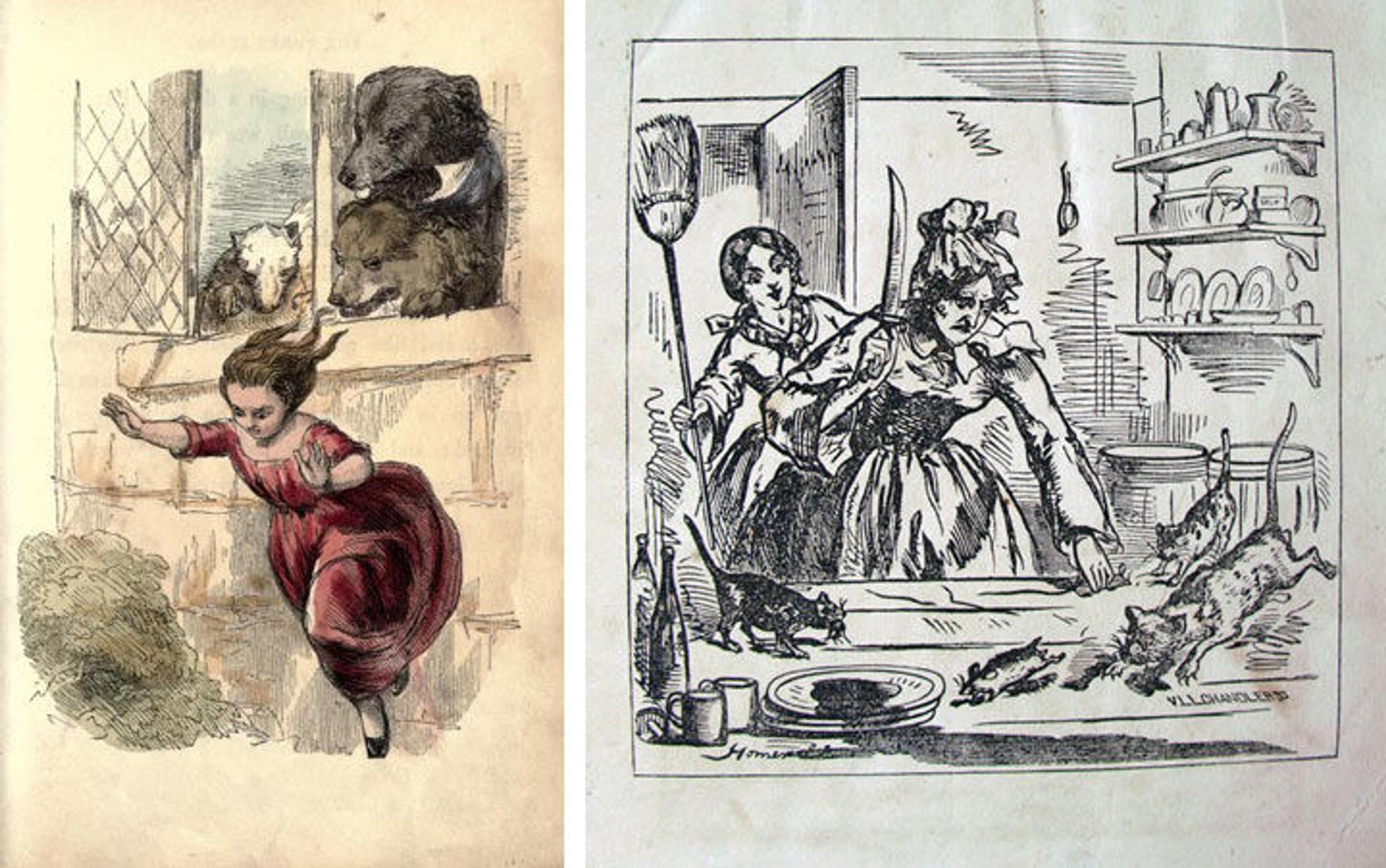

Weir was best known as an animal fancier and his illustrations of cat tea parties and numerous varieties of strutting poultry, such as the Golden Pencilled Hamburghs, brought him fame. Weir's version of The Three Bears appeared in a number of British and American editions, including Joseph Cundall's A Treasury of Pleasure Books for Children. The New-York Historical Society's Patricia D. Klingenstein Library generously loaned us a copy that I installed in a small case next to Guy's painting in the gallery. The text describes the central protagonist as Little Silver Hair not Golden Locks. Her name derives from earlier versions of the fairy tale in which the intruder was an old woman.

Left: Harrison Weir (British, 1824–1906). A Treasury of Pleasure Books for Young Children. Published by Grant & Griffith and Joseph Cundall, London, 1850. Hand-colored engraving. New York Historical Society Library. Right: Homer (American, 1836–1910). Eventful History of the Three Blind Mice. Published by E. O. Libby & Co., Boston, 1858. Hand-colored wood engraving. Private collection

While The Three Bears successfully thwarted their home invasion, other animals did not fare so well. American artist Winslow Homer began his career as a children's illustrator, honing his narrative talents in the gruesome 1858 poem Eventful History of Three Blind Mice and How They Became Blind. The frontispiece shows the climax of the story: the farmer's wife cutting off the mice's tails with a carving knife.

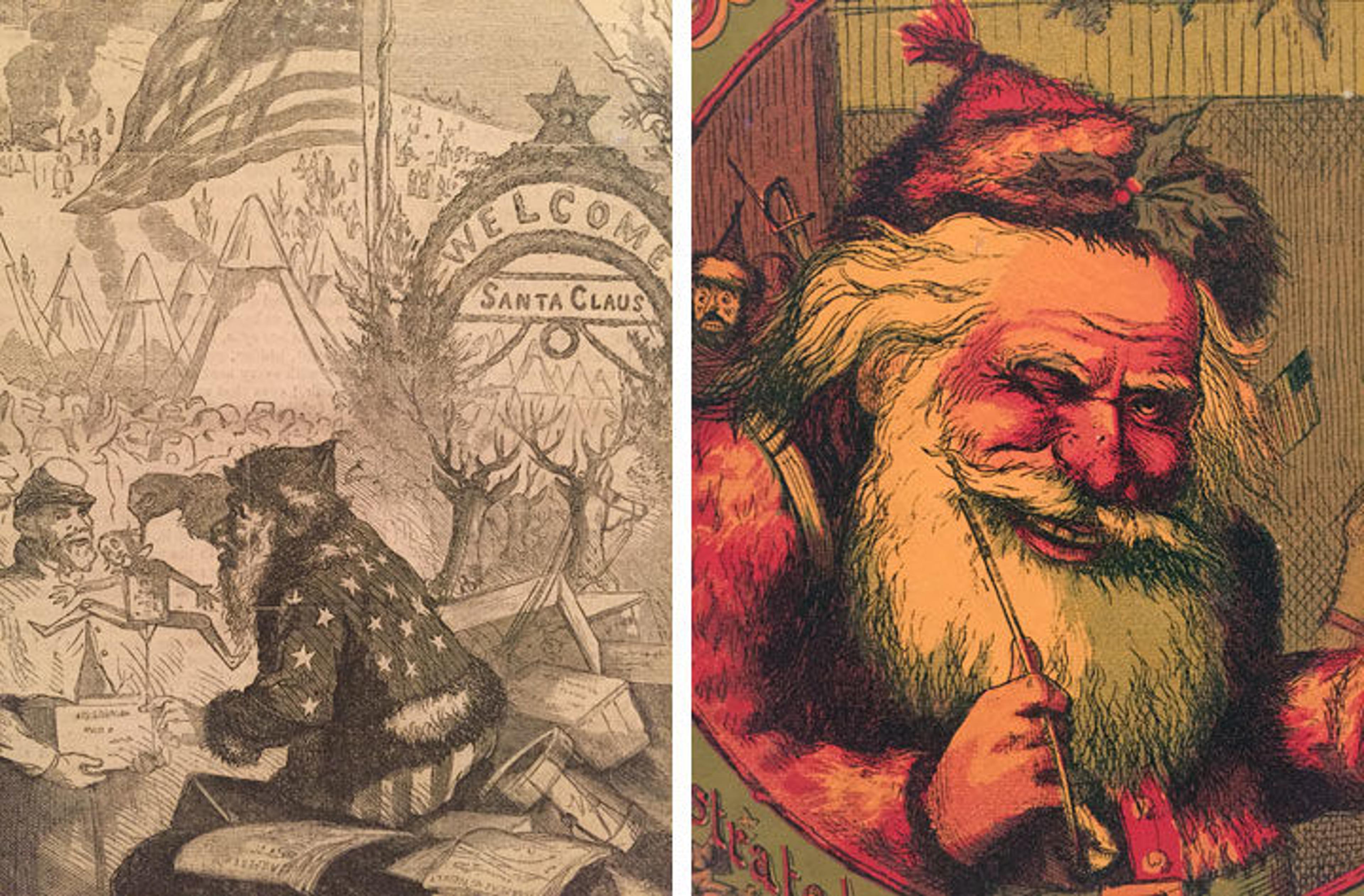

Tailored to a burgeoning marketplace centered on children, innovative printing techniques were adopted in advertisements for everything from Christmas to the circus. On January 3, 1863, Harper's Weekly featured the first image of Thomas Nast's Santa Claus. Arriving by sleigh to a Union army camp, Santa distributes gifts and entertains the troops with a jumping jack in the likeness of Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

Left: Thomas Nast (American, 1840–1902). Santa Claus in Camp (from Harper's Weekly) (detail), January 3, 1863. Wood engraving; Sheet: 14 3/4 x 10 9/16 in. (37.4 x 26.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1929 (29.88.4[7]). Right: Thomas Nast (American, 1840–1902). Visit of St. Nicholas (detail), 1872. Published in New York by McLoughlin Bros. Color lithograph. Private Collection

During the dark days of the Civil War, Santa was conceived as a surrogate male figure, generous and kind, who kept families that were torn apart in reality together in spirit. After the war, Nast's portrayal of Santa became a staple of children's picture books, calendars, and Christmas cards.

In the small West Virginia town of Jerryville in 1871, Charles Caleb Ward painted Coming Events Cast Their Shadows, an image of children gazing at brilliantly colored posters announcing the imminent arrival of P. T. Barnum's Grand Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan & Hippodrome. As the posters announce, the spectacular circus featured Egyptian mummies, life-size mechanical dolls, exotic animals, and even scandalous artworks like Hiram Powers's sculpture The Greek Slave.

Charles Caleb Ward (American, ca. 1831–1896). Coming Events Cast Their Shadows Before (detail), 1871. Oil on wood; 10 1/8 x 8 in. (25.7 x 20.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Susan Vanderpoel Clark, 1967 (67.155.2)

The poster to the far left of the image depicts one of Barnum's human curiosities, Ann E. Leak, the "armless wonder." Born in Georgia on December 23, 1839, Leak survived a sickly childhood and persevered, learning to use her feet as most use their hands. When the Civil War left her family in financial ruin, she joined Barnum's American Museum and later his circus. Leak went about her everyday activities of hair braiding, knitting, and writing as a performance. In The Autobiography of Miss Ann E. Leak, Born Without Arms: Containing an Interesting Account of Her Early Life and Subsequent Travels in the United States, she wrote:

My lot was not one of my own choosing, but such as Providence had assigned me, and my feet seemed to be directed in the path that I was about to tread. It is the doom of man that his sky should never be altogether without clouds.

It is heartbreaking to read Ann's acceptance of her tragic circumstances and infuriating to remember her as one of Barnum's attractions.

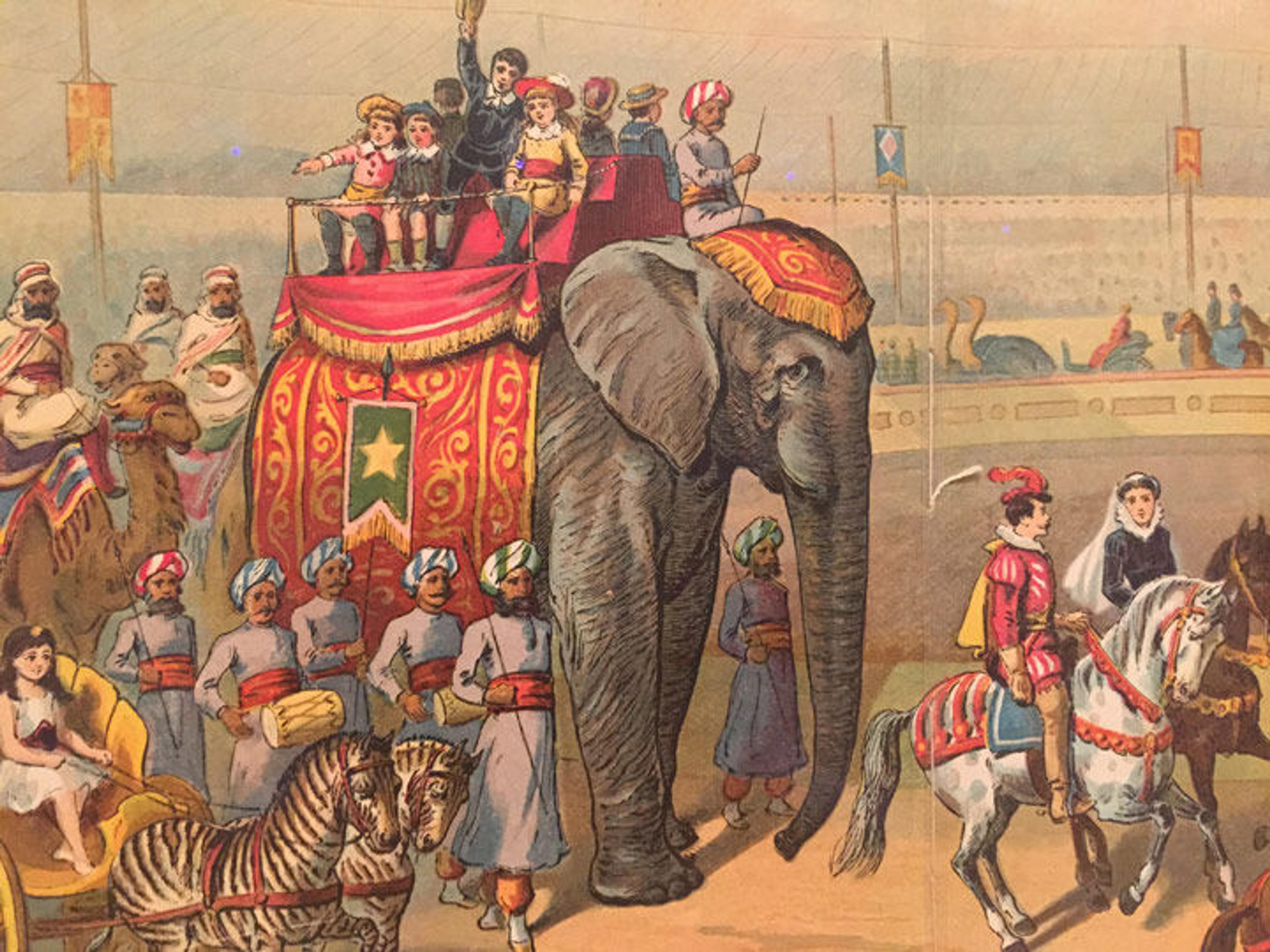

Children's picture books celebrated the circus. Bright chromolithography brought the show's grand procession and animated crowds to life in A Peep at the Circus, which was published five years after Barnum introduced Jumbo, an African bull elephant, into the big top.

A Peep at the Circus, 1887. Published by McLoughlin Brothers (New York, NY). Illustrations: color lithography; 12 x 10 x 1/4 in. (30.5 x 25.4 x 0.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1971 (1971.564.69)

Jumbo was a marketing bonanza and appeared on countless posters. For years, elephants became the superstars of Barnum' Circus (now Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus), generating tremendous excitement when they would arrive in cities and towns across the country marching through tunnels and down main streets. The broad dissemination of illustrated posters and advertisements at the turn of the 20th century secured a legacy for printmakers. But some traditions are meant to be broken, and just as circuses years ago rejected exploiting humans, this year Barnum's legendary circus retired their elephants.

From Randolph Caldecott's exquisite and humorous original watercolors for the book The House that Jack Built to Winslow Homer's maturation as a visual storyteller of childhood, there is much to see, remember, and discuss in Printing a Child's World. Visit the exhibition to find out more about the relationships between these extraordinary printmakers and painters and what delighted and amazed you as a child.