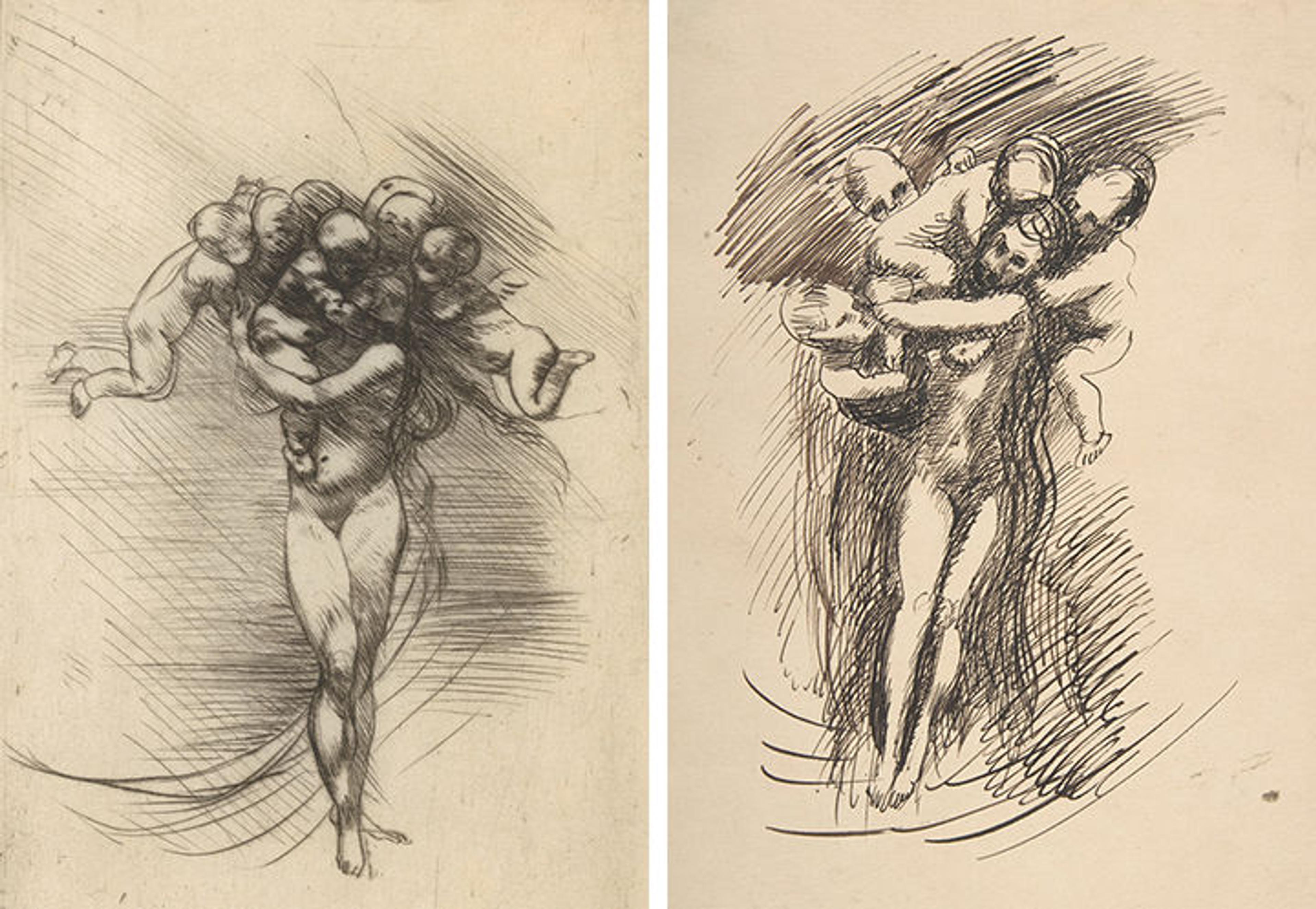

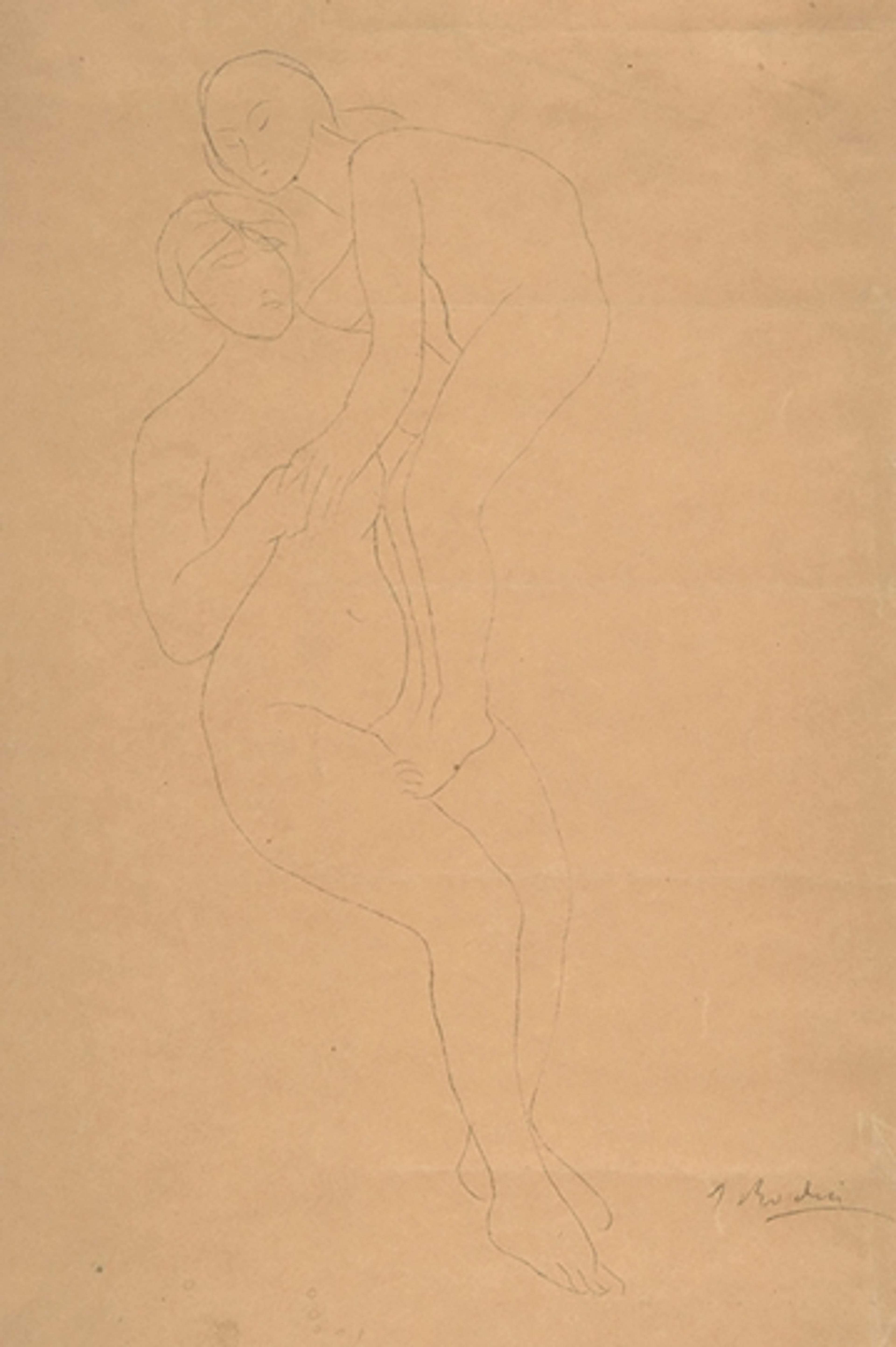

Left: Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). Spring (Le Printemps), 1882–88. Drypoint, 5 13/ 16 x 3 15 / 16 in. (14.8 x 10 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1966 (66.686.2). Right: Ernest Durig (French, 1894–1962). Forged drawing related to Rodin's Le Printemps. Pen and dark brown inks, 9 15/16 x 6 13/16 in. (25.3 x 17.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Miss Doris Meltzer, 1960 (60.680)

«At the outset of preparing Rodin at The Met, there were 24 drawings in The Met collection attributed to Auguste Rodin; now there are 19 with secure attributions. The pervasiveness of forgeries of Rodin's drawings is a well-known problem in the field. The Met, therefore, is extremely fortunate that the majority of drawings in the collection were purchased during the artist's lifetime—seven through Alfred Stieglitz's gallery 291 in New York in 1910, and six sent directly by the artist to the Museum in 1913. The institution was not immune, however, to the ubiquity of fake Rodin drawings, a number of which entered the collection as gifts from the 1960s through the '80s. Of the five recently reevaluated works, two drawings turned out to be by known forgers, two by anonymous hands, and one is actually a print.»

The issue of forged Rodin drawings came to public attention in the United States in 1965, when Dorothy Seiberling published an exposé in LIFE magazine following the death of one of the artist's most prolific forgers, Ernest Durig. In 1971–72, art historians Albert Elsen and J. Kirk Varnedoe brought scholarly analysis to the controversy with their pioneering study and exhibition, Rodin Drawings: True and False at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. When a number of the drawings in The Met collection started to look suspicious to me, I was grateful to be able to turn to today's leading authority, Christina Buley-Uribe, who is currently preparing a catalogue raisonné of Rodin's drawings and paintings. Buley-Uribe not only confirmed that The Met collection contains four fakes, she also offered attributions for two of the false drawings to the two named forgers: Durig and Odilon Roche.

Swiss-born Durig claimed to be Rodin's last student. One surviving photograph of the two together suggests they met in 1915 in Rome, where Rodin stayed for a number of months during World War I. Durig immigrated to the United States in 1928 and soon thereafter began to exhibit and sell his forgeries as supposed gifts from his master.

Left: Ernest Durig (French, 1894–1962). Forged drawing related to Rodin's Le Printemps. Pen and dark brown inks, 9 15/16 x 6 13/16 in. (25.3 x 17.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Miss Doris Meltzer, 1960 (60.680)

One of Durig's strategies in making his fakes, evident in the example in the collection, was to source subjects from known works in Rodin's oeuvre and make drawings that look like they could relate. Previously catalogued as a "Study for Le Printemps," it is now clear that the drawing is not preparatory to Rodin's drypoint Spring (Le Printemps), but is rather based on it. The oversized proportions of the putti in relation to the central figure, as well as her bizarre anatomy, confusion with the background hatching, and overall weightlessness are all signs this drawing is not by Rodin.

While forgeries by Durig are most common in American collections, Roche was busy in France. A merchant of artists' supplies and an amateur painter, Roche collected Rodin's drawings and his mark (a red square surrounding the initials O. R.) came to signify a good provenance for a time. Roche proved a talented forger and his drawings even found their way into the collections of those who knew Rodin well, including his friend and biographer, Judith Cladel, and his bronze founder, Eugène Rudier.[1]

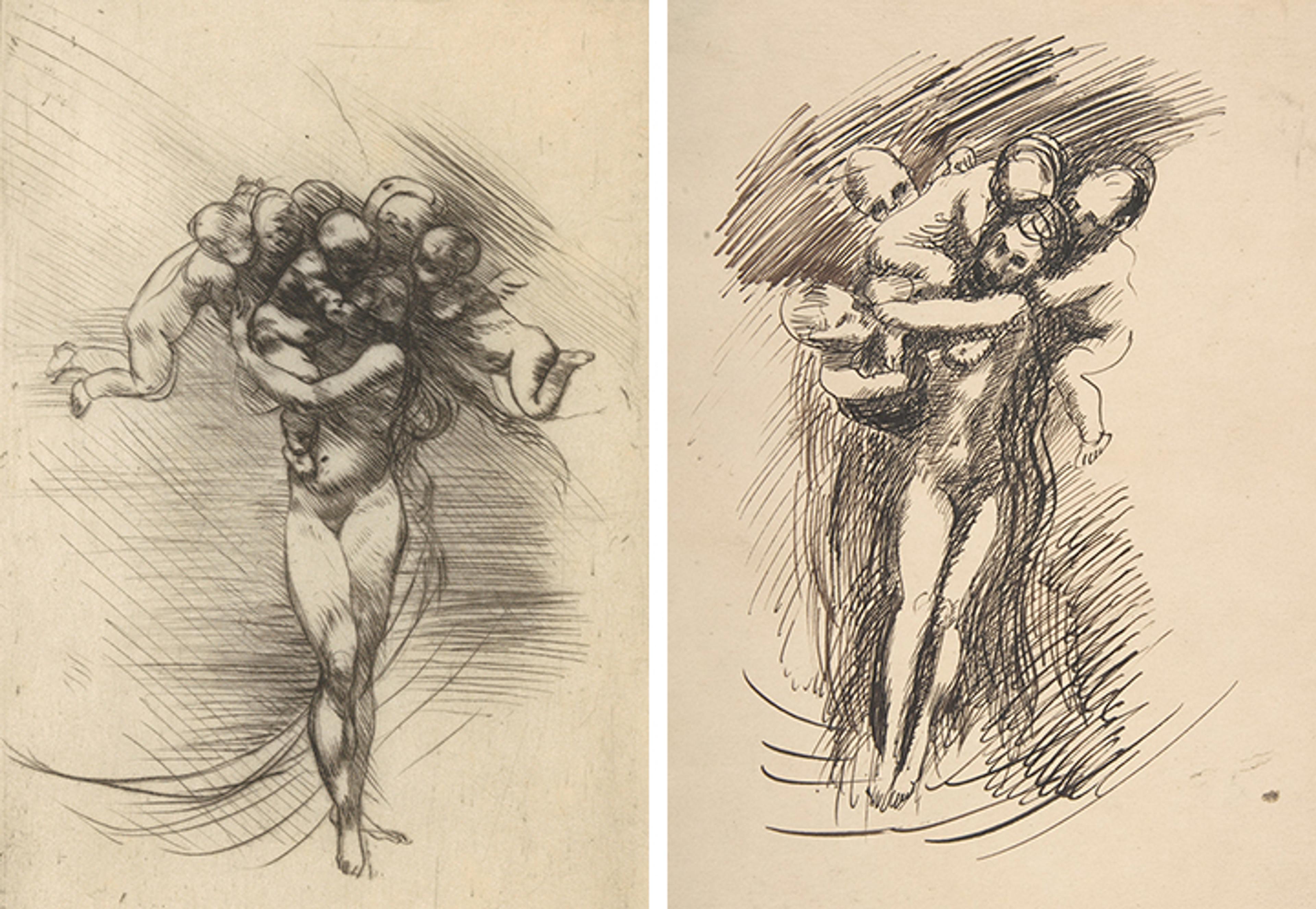

Right: Odilon Roche (French, 1868–1947). Standing Female Nude, not dated. Graphite and watercolor, 11 x 9 in. (28 x 22.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Gregoire Tarnopol, 1979, and Gift of Alexander Tarnopol, 1980 (1980.21.16)

The incoherent and meaningless hatching in the background of Standing Female Nude—in contrast to the expressive graphite strokes found in The Embrace, for example—is one distinguishing feature of a Roche forgery. Additionally, the flecks of concentrated pigment are not found in genuine Rodin watercolors. Rodin masterfully exploited the effects of the medium, embracing the splotches and tidelines that result from a very wet brush, but his works do not typically exhibit such random streaks as those seen on the right side of the Roche drawing.

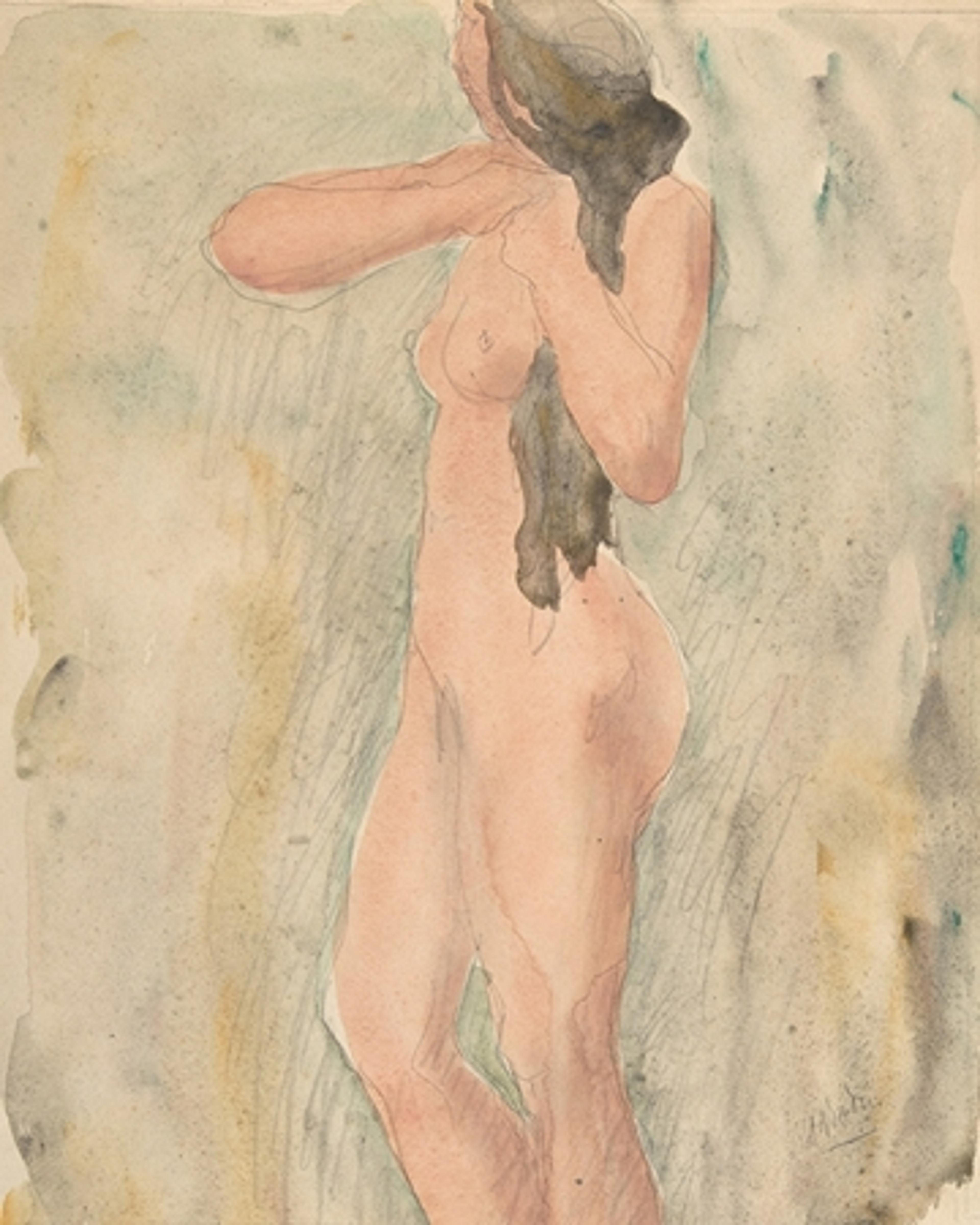

Another curiosity of The Met collection that Buley-Uribe helped bring to light is a copy of a reproduction of a Rodin drawing published in the journal La Plume in 1900. The shaky, disjointed lines of the copy exaggerate the searching swells of Rodin's line as conveyed by the print, which likely reproduces one of his drawings made without looking at the sheet.

Left: Anonymous; formerly attributed to Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). Copy after a reproduction of a Rodin drawing, not dated. Pen and black ink, 14 5/16 x 9 1/4 in. (36.4 x 23.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Gregoire Tarnopol, 1971 (1971.253.4). Right: Reproduction of a Rodin drawing in La Plume no. 278 (November 15, 1900), 681. Image courtesy Gallica, the Bibliothèque nationale de France digital library

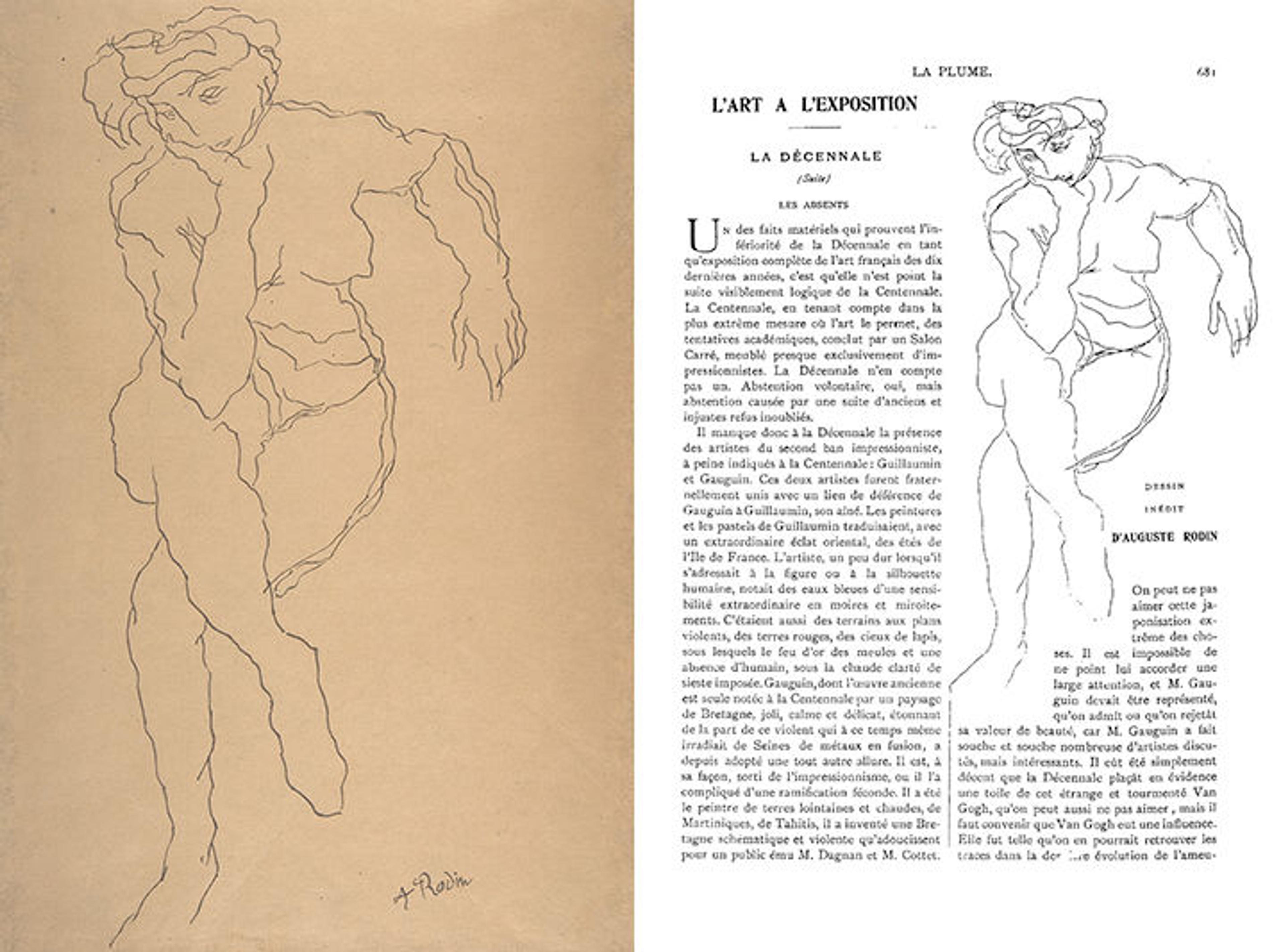

One work formerly catalogued as a drawing turned out to be a print. It is easy to understand how such a mistake could be made, knowing the great skill of lithographer Auguste Clot, with whom Rodin worked to translate some of his drawings into prints. They notably collaborated on the illustrations for Octave Mirbeau's Le Jardin des Supplices, a high-point of color lithography in the period. A print from that series, such as "Elle semblait. . . ," makes evident both Clot's astounding ability to mimic the qualities of graphite and watercolor, and how easily his lithographs might be confused with original drawings.

Auguste Clot (French, 1858–1936) after Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). "Elle semblait revenir d'un long, d'un angoissant sommeil," from Le Jardin des Supplice, 1902. Color lithograph, 12 11/16 x 9 15/16 in. (32.3 x 25.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1923 (23.19.1[38])

In the case of the composition with two figures, it took looking at the lines under a microscope in the Paper Conservation lab to confirm that they were, in fact, printed rather than drawn. The drawing on which the lithograph is based is in the collection of the Musée Rodin. Another version with watercolor sold at auction in March 2014.

The opportunity to study our holdings closely and scrutinize works that entered the collection at various points in the Museum's history is one of the great benefits of a collection-based exhibition such as Rodin at The Met.

Right: Auguste Clot (French, 1858–1936) after Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). Sapphic Couple, 1898–1905 or later. Lithograph, 15 5/8 x 9 3/4 in. (39.7 x 24.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Scofield Thayer, 1984 (1984.1203.121)

Note

[1] Christina Buley-Uribe, "Du vrai et du faux. Les dessins de Rodin du fonds du musée d'Orsay," La Revue des musées de France (2014), 85.

Related Content

Read a blog series on Rodin at Now at The Met.

See more digital content related to Rodin at The Met.