«Autumn is full of good things: pumpkins, turning leaves, cable-knit sweaters, and good reasons to spend cold days indoors at The Met. There is plenty to see in the Museum with the season in mind, from allegorical depictions of autumnal themes to abstract renderings of fall landscapes. Here are five works from five eras to see during your next trip to The Met Fifth Avenue.»

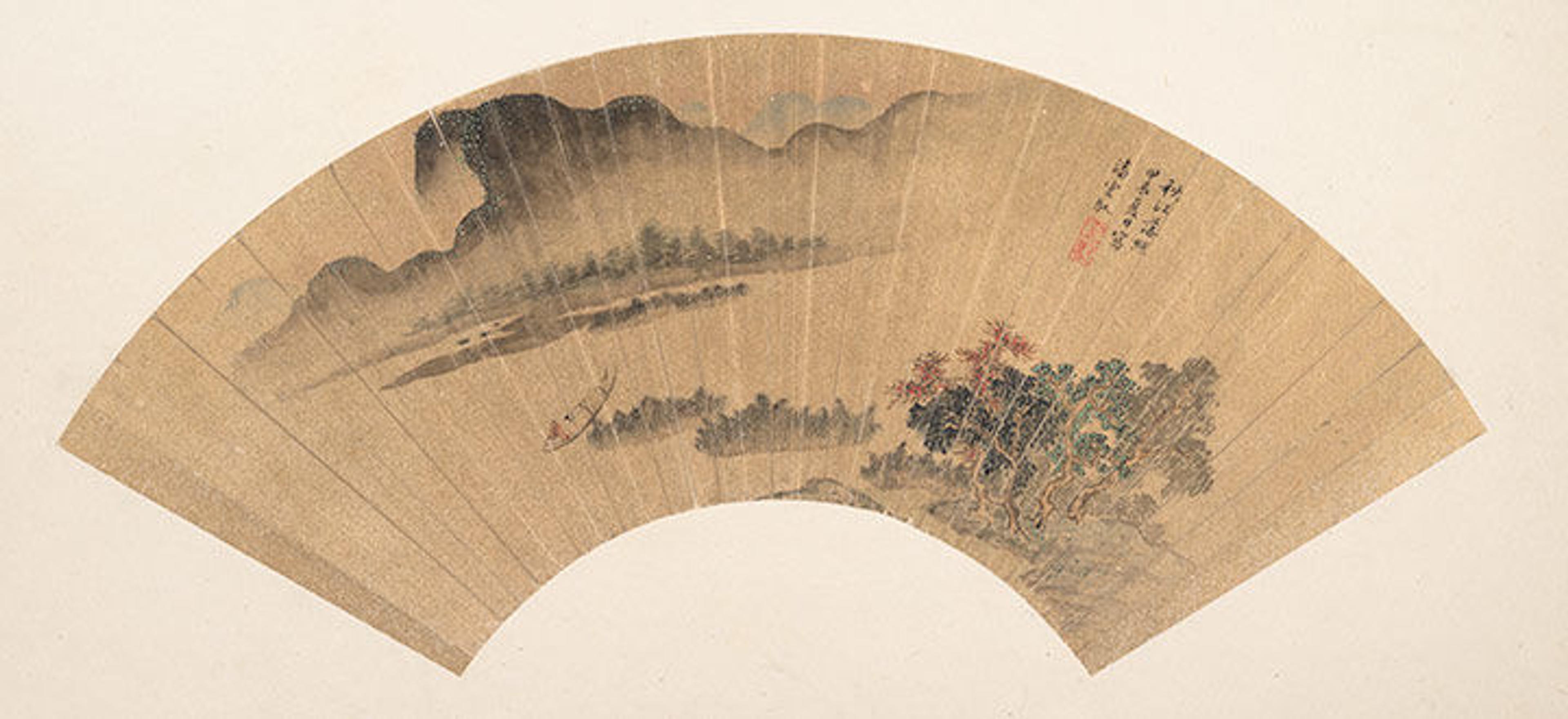

Pan Yunyu (Chinese, active ca. 15th–16th century). Setting Sun on the Autumn River, 1604 or 1664. Folding fan mounted as an album leaf; ink and color on gold paper, 6 1/4 x 19 in. (15.9 x 48.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1913 (13.100.79)

Stop 1: Gallery 216 (Asian Art)

Autumnal Work: Setting Sun on the Autumn River

Fall is rarely a time of respite. Instead, it tends to be when we return to work or school after a spell of rest in the summer. But Pan Yunyu, a Chinese artist active during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), used an autumn setting as the backdrop for this calm scene. At the left of the folding fan, the artist has painted a solitary, peaceful, untroubled figure in a small raft. The water theme is no accident: artists of the period often used rivers as emblems of dreamy simplicity.

George Inness (American, 1825–1894). Autumn Oaks, ca 1878. Oil on canvas, 20 3/8 x 30 1/8 in. (54.3 x 76.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of George I. Seney, 1887 (87.8.8)

Stop 2: Gallery 761 (American Paintings and Sculpture)

Autumnal Work: Autumn Oaks

The American painter George Inness finished this picture about 1878, after a four-year sojourn in Europe with his family. In Rome, he was drawn to the work of Claude Lorrain, but it was an autumn day in New England, to where he had moved in 1874, that inspired this painting. The work is notable in part because of its lack of many small details, which Inness set aside in favor of a more poetic, contemplative rendition of a central group of trees framed by a darkening sky.

François Boucher (French, 1703–1770) and Workshop. Allegory of Autumn, 1753. Oil on canvas, 44 3/4 x 63 3/4 in. (113.7 x 161.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gift, 1969 (69.155.1)

Stop 3: Gallery 525 (European Sculpture and Decorative Arts)

Autumnal Work: Allegory of Autumn

This allegory of autumn by the Rococo painter François Boucher and his workshop is tucked above one door of a Parisian period room. Originally built between around 1736 and 1752 by the architect Jacques Gabriel, the room, which is now installed at The Met, also has an allegorical depiction of Lyric Poetry. For autumn, Boucher and his assistants rendered an image of Cupid handing fruit to two putti below, who are flanked by a tambourine and a wind instrument. It's an image of youthful abundance and joy—a perfect summary of healthy, seasonal change.

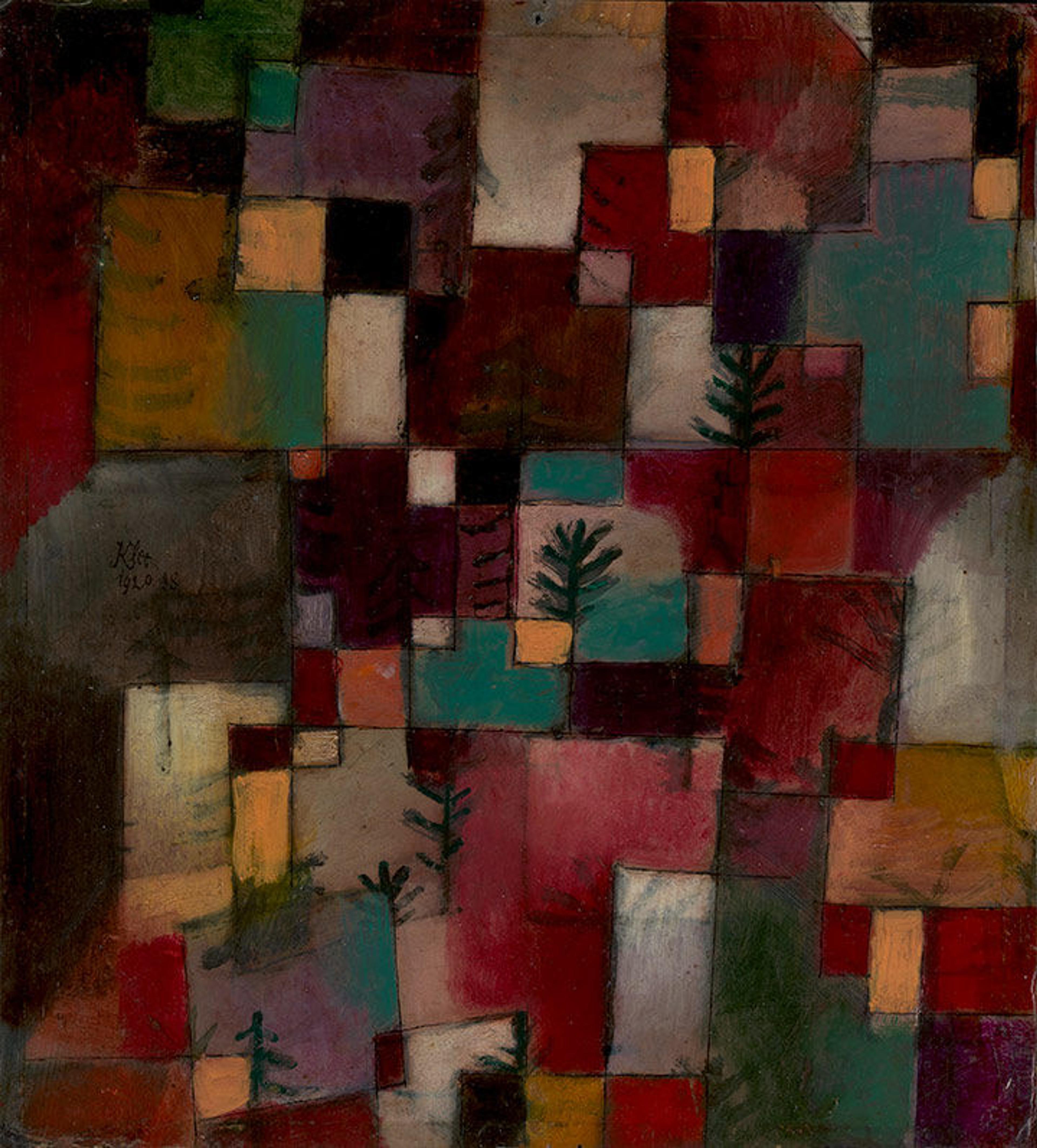

Paul Klee (German [born Switzerland], 1879–1940). Redgreen and Violet-Yellow Rhythms, 1920. Oil and ink on cardboard, 14 3/4 x 13 1/4 in. (37.5 x 33.7cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Berggruen Klee Collection, 1984 (1984.315.19)

Stop 4: Gallery 912 (Modern and Contemporary Art)

Autumnal Work: Redgreen and Violet-Yellow Rhythms

The vivid colors in this painting of trees by Paul Klee have long been appealing, and the painting has gone through several hands. From 1922 to 1958, it belonged to the art historian Sophie Küppers, who was married to the Russian Constructivist El Lissitzky. The couple lent the work from 1926 to 1930 to the Provinzialmuseum in Hanover. In 1974, it came to into the collection of Heinz Berggruen, a major collector of paintings by Klee. Ten years later, Berggruen donated 90 works by the artist to The Met, including this picture, which today sits in a gallery devoted in part to his collection.

Marble statue of Tyche-Fortuna restored with the portrait head of a woman. Roman, Imperial, Late Flavian or Early Trajanic (1st or 2nd century A.D.). Marble, 75 x 26 x 23 in. (190.5 x 66 x 58.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1961 (61.82.2)

Stop 5: Gallery 168 (Greek and Roman Art)

Autumnal Work: Marble statue of Tyche-Fortuna restored with the portrait head of a woman

In ancient Rome, Fortuna was originally a fertility goddess, which is why this figure carries a cornucopia (today a symbol of the fall harvest). But she also became identified with the Greek goddess of fate and luck, Tyche (the ship's rudder symbolizes that she can steer destiny). This statue was indeed lucky: after its original head was lost, it was outfitted in the 18th century with the portrait head of an unknown Roman woman with a fashionable hairdo. The work once belonged to William Fitzmaurice, 1st Marquess of Lansdowne, who, as the British Prime Minister, oversaw the end of the American Revolution and the Treaty of Paris in fall 1783. Until 1930, the statue was displayed in the dining room of Lansdowne House in London. Today, that dining room also lives in The Met.