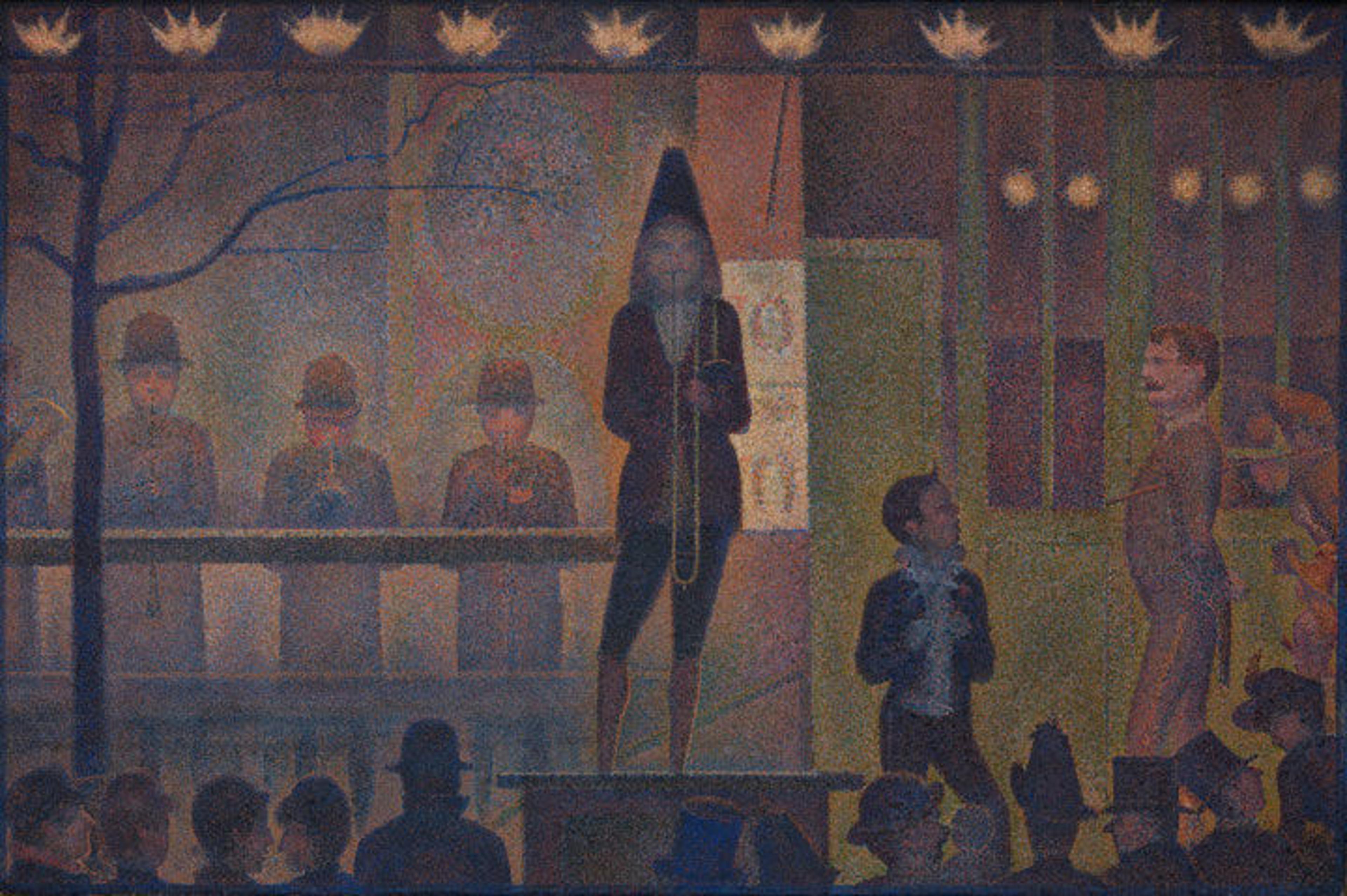

Georges Seurat (French, 1859–1891). Circus Sideshow (Parade de cirque), 1887–88. Oil on canvas, 39 1/4 x 59 in. (99.7 x 149.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Stephen C. Clark, 1960 (61.101.17)

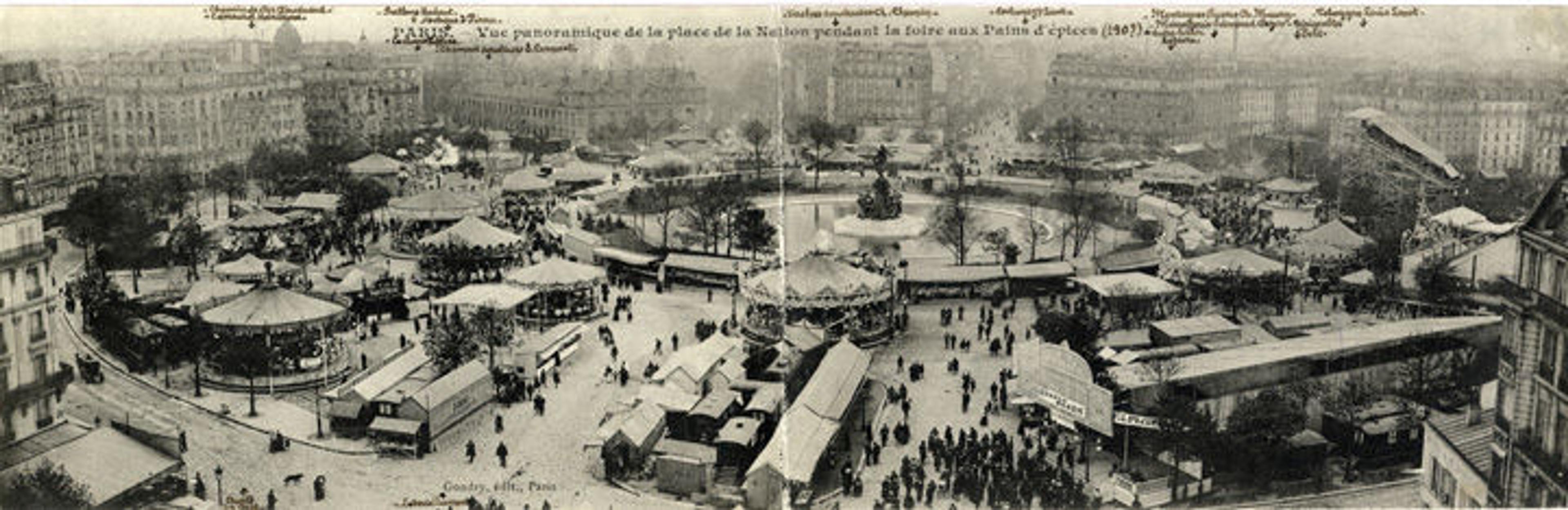

«Georges Seurat's most evocative and stylized painting, Circus Sideshow (Parade de cirque)—a highlight of The Met collection and the centerpiece of the exhibition Seurat's Circus Sideshow on view through May 29—is known to represent a specific traveling circus troupe performing at a seasonal fair in Paris in the spring of 1887. Seurat made studies of his visit to the Gingerbread Fair (Foire au pain d'épice), held each year in a working-class district around the place de la Nation during the three weeks after Easter Sunday, which fell on April 10 that year.»

Panoramic view of the place de la Nation, Paris, during the Gingerbread Fair, ca. 1900. Musée des Civilisations de l'Europe et de la Méditérranée, Marseille

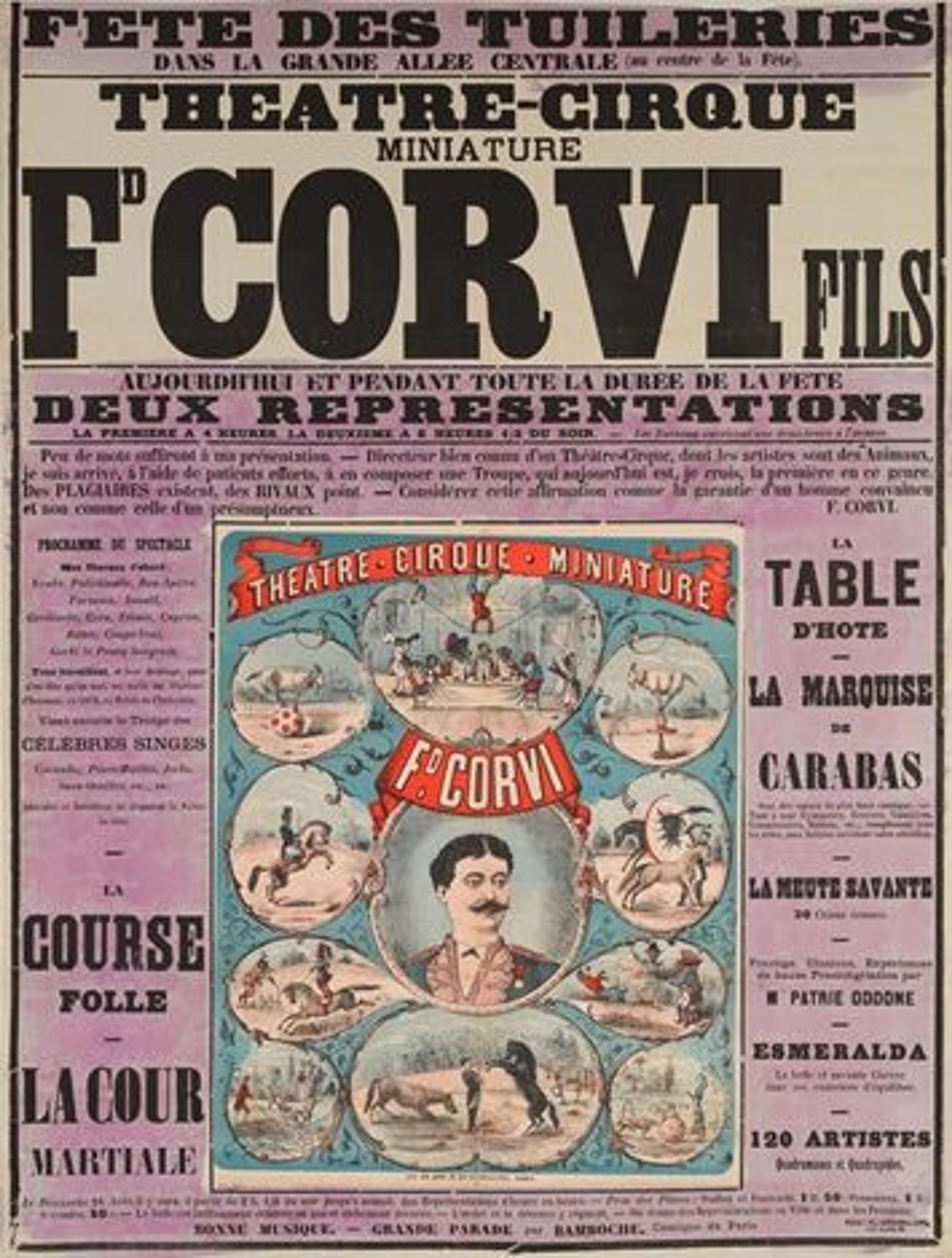

Inspired by what he saw there, Seurat developed a composition featuring the Corvi Circus and its sideshow act: the "come one, come all" teaser attraction intended to capture the attention of fairgoers and entice them to buy tickets to the spectacle under the tent. Critic Gustave Kahn first associated Circus Sideshow with this particular troupe in his review of the 1888 Salon des Indépendants where the painting made its debut. Kahn recognized the "gaudy tents" from the colorful, yet abstracted, backdrop in the picture. Similar ovals to those to the left of the trombonist are visible in photographs and posters of Corvi Circus.

Left: Affiches Américaines, Charles Lévy, Paris (printer). Fair at the Tuileries: F. Corvi's Miniature Theater-Circus, ca. 1882–88. Color lithograph, 43 1/8 x 33 1/8 in. (109.5 x 84 cm). Musée Carnavalet–Histoire de Paris

In preparation for this exhibition designed to illuminate the conception of Seurat's picture, the curatorial team—Susan Alyson Stein, Engelhard Curator of Nineteenth-Century Painting at The Met, Professor Richard Thomson of the University of Edinburgh, and myself, their research assistant—set out to track down contemporary images and accounts of this circus and fair. We included many of our findings in the exhibition in order to introduce visitors to Seurat's subject matter and orient them to his mysterious composition.

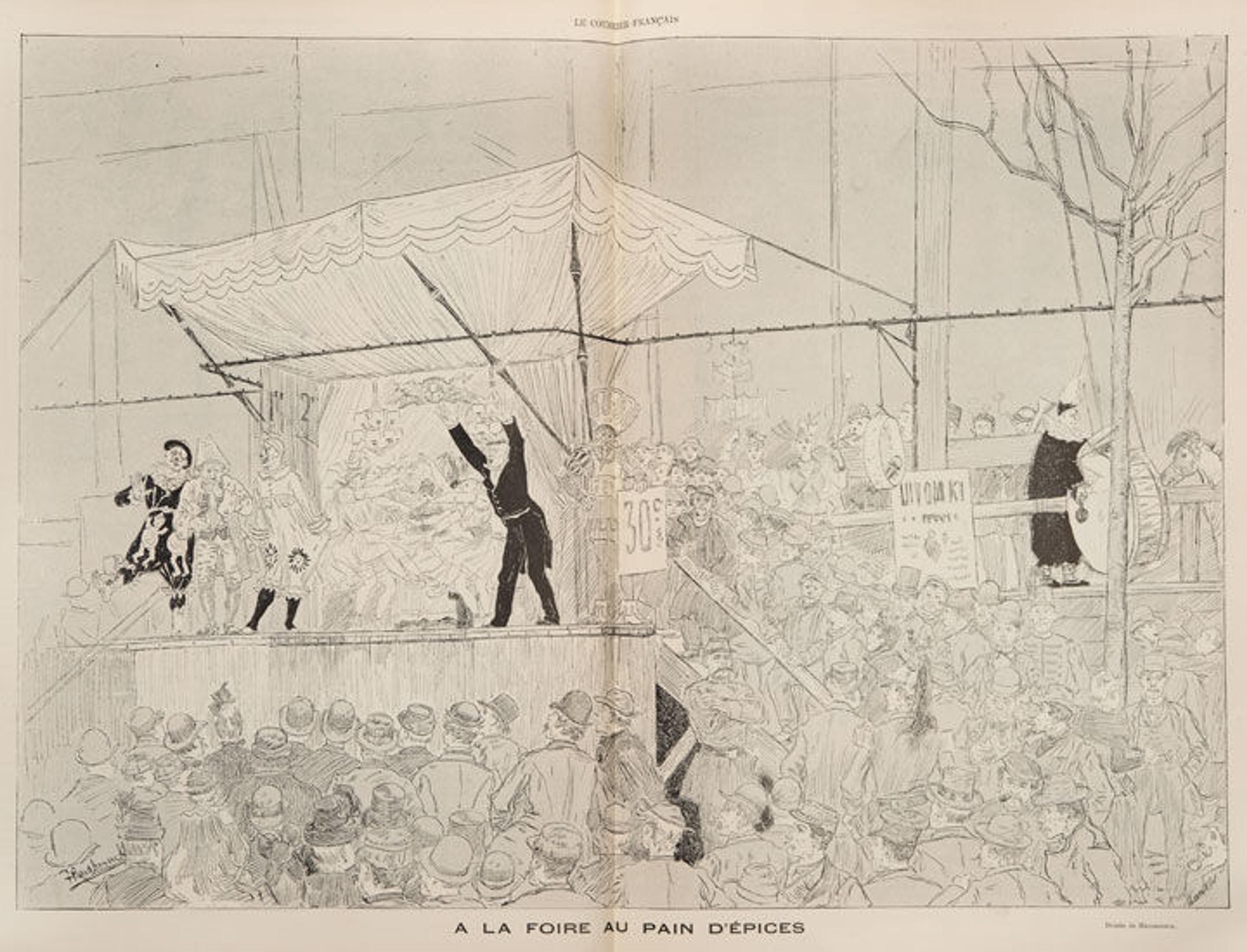

We began with images that had been identified previously by scholars, such as the illustration below from a French journal of the 1887 Gingerbread Fair that Seurat attended. Several elements from his painting appear here: the crowd gathering in front of a temporary stage, the players from the Corvi band at right, the spindly tree, the gas-jetted pipe that provided a source of light after dark, and even the poster advertising tickets for 30 centimes.

Oswald Heidbrinck. At the Gingerbread Fair, from Le Courrier français, May 1, 1887. Photomechanical print, 15 7/8 x 22 1/4 in. (40.2 x 56.6 cm). Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University, Museum Purchase

Photographs like the one on the postcard below help make sense of the space that Seurat depicted as flattened geometric forms and represent the cast of characters that populate his set. Notice the musicians lined up behind the balustrade at left. The gentleman wearing tails in the center is none other than Ferdinand Corvi, the ringmaster and proprietor of the circus also featured in the central oval of the poster above and, as Richard Thomson proposes for the first time in the exhibition catalogue, painted by Seurat in profile on the right side of Circus Sideshow. Here, two decades later, he has taken on a more rotund, middle-aged form, but his signature mustache and dapper style are instantly recognizable. Could it be that the man with a pageboy haircut to the left, standing on a dais in front of the diagonal railing, is Seurat's trombonist, also plumped up with age?

The Corvi Circus at the Gingerbread Fair, cours de Vincennes, Paris, 1906. Postcard. Musée des Civilisations de l'Europe et de la Méditérranée, Marseille

Founded in 1846, the Corvi Circus was known for its animal acts: a goat named Esmeralda who could balance on a ball, barrel, or bottle; acrobatic horses and dogs; and monkeys trained to perform amusing scenes like a firing squad and dinner party (see illustrations in the poster above). At the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, I consulted an archival file with advertisements and articles about this well-known circus, including an interview with Ferdinand Corvi, in which he described the "enviable" dietary regimen of his monkeys: wheat and milk soup in the morning, vegetables cooked in broth and warm sweetened wine for lunch, and bread with seasonal fruits in the evening.

Seurat was certainly aware of the circus's signature animal attractions and included a frontal view of a pony standing beside M. Corvi in his preparatory drawing for the right side of the composition. But he ultimately eliminated every trace of Corvi's "monkey business" from the painting, perhaps to achieve the balance, harmony, and enigmatic mood he was after.

Right: Georges Seurat (French, 1859–1891). Ferdinand Corvi and Pony, 1887–88. Conté crayon on paper, 11 5/8 x 8 5/8 in. (29.5 x 22 cm). Private collection

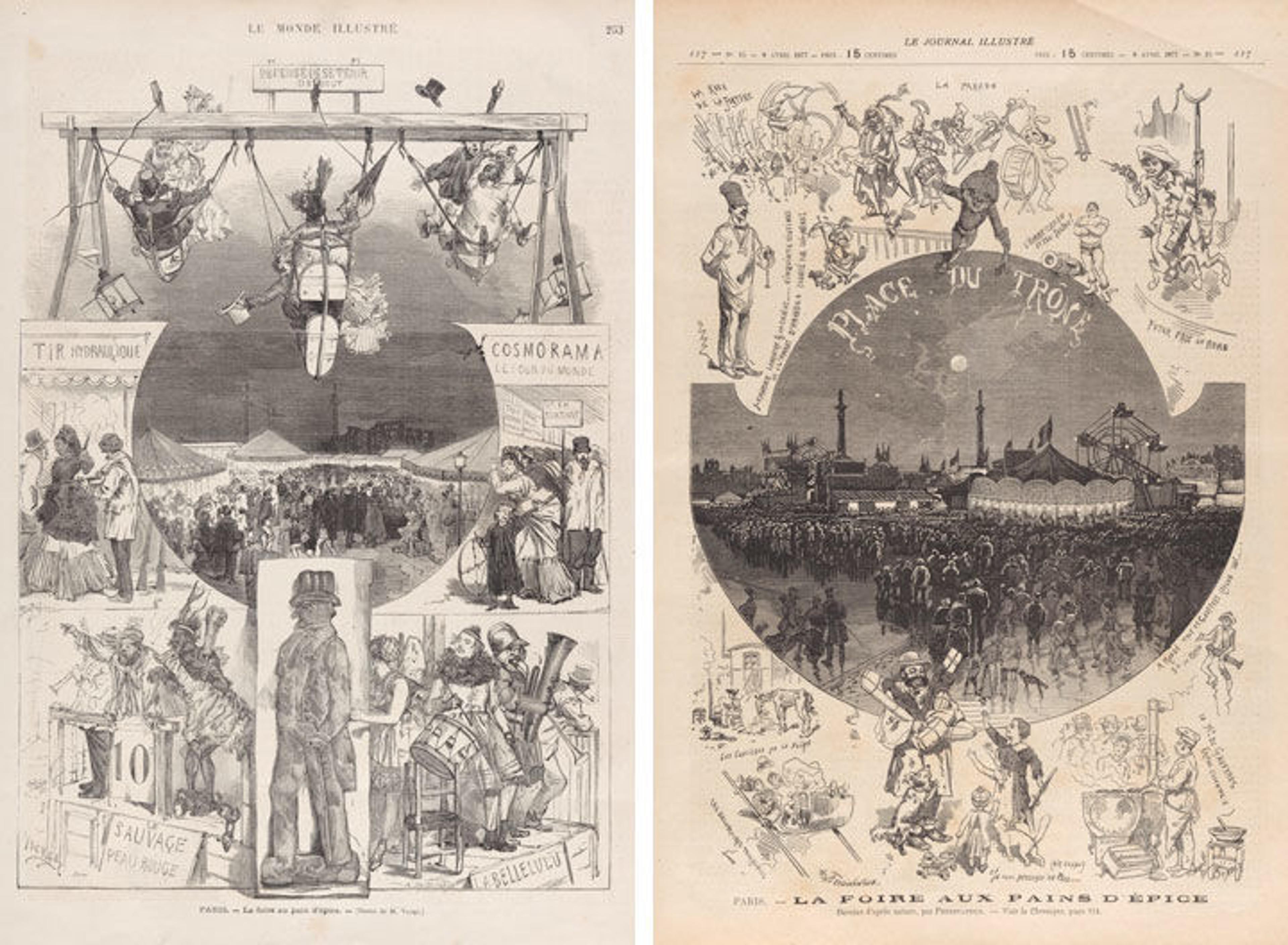

Even though Seurat minimized specific detail in Circus Sideshow, his contemporaries would have immediately recognized the imagery of traveling fairs, which had been popular in France since the Middle Ages and were frequently discussed and depicted in the press. Through the wonders of internet research, we were able to discover and secure plates from 19th-century illustrated journals.

These two prints below, from 1873 and 1877, represent the variety of offerings at the Gingerbread Fair, including musical performances, a merry-go-round, thrill rides, a human canon, a wheel of fortune, and the tasty confection for which the fair was named, available in a host of different shapes. Many of the attractions are familiar to today's audiences, while others, like the "savage red skin" (Le Sauvage Peau Rouge) represented onstage in shackles, were considered novelties at the time but are now seen as offensive and dehumanizing.

Left: Daniel Vierge (Spanish, 1851–1904). Paris—The Gingerbread Fair (La Foire au pain d'épice), from Le Monde illustré, April 19, 1873. Wood engraving, 14 5/8 x 10 1/2 in. (37 x 26.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Right: Alexandre Ferdinandus (pseudonym of F. Avenet). (French, died 1888). Paris—The Gingerbread Fair (La Foire aux pains d'épice), from Le Journal illustré, April 8, 1877. Wood engraving, 14 7/8 x 11 in. (37.7 x 28 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

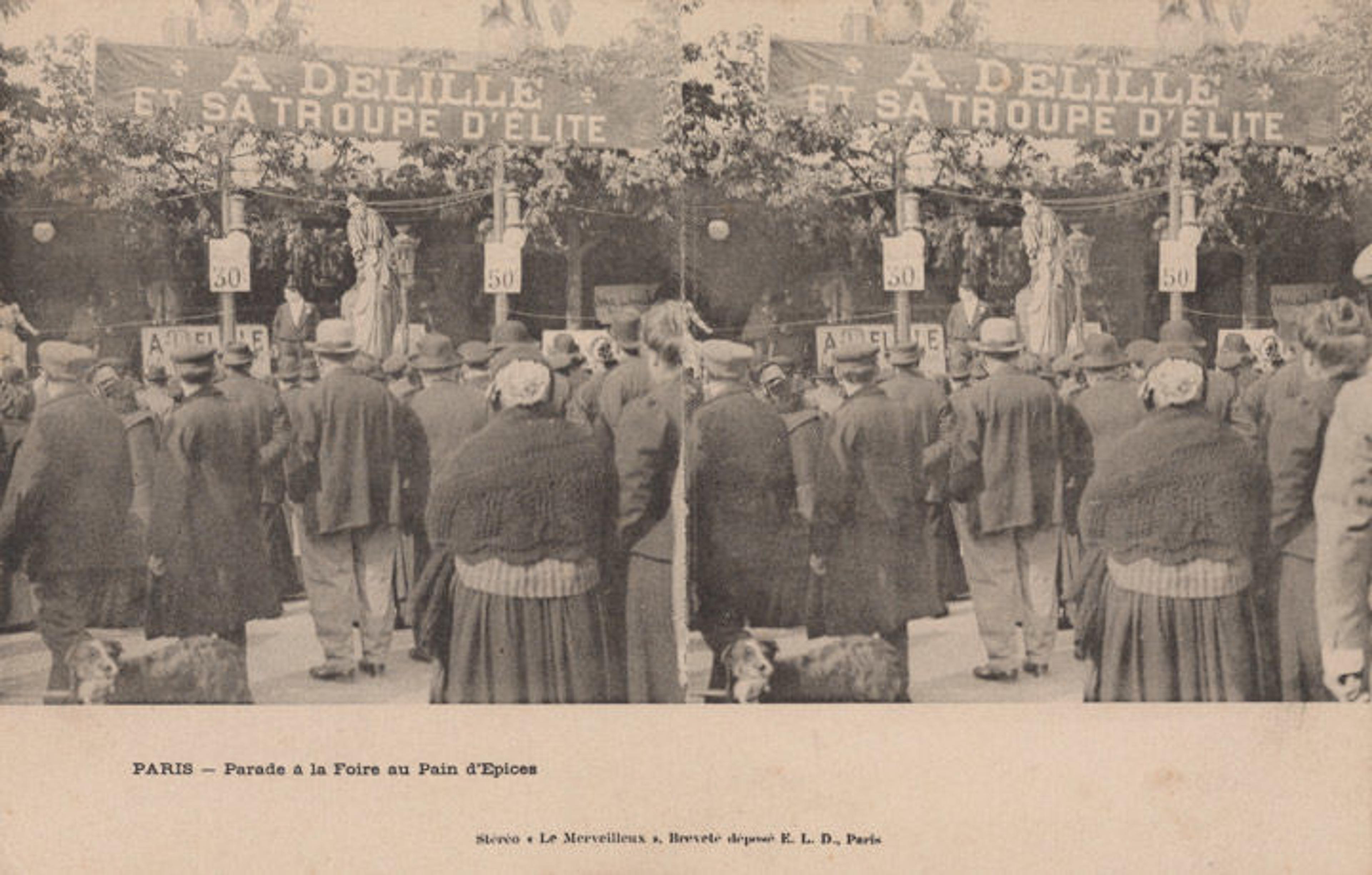

We supplemented the journal illustrations with vintage postcards of sideshow performances at the fairs, including one that transforms into a three-dimensional image when seen through the stereoscope viewer in the galleries.

Sideshow at the Gingerbread Fair, Paris (Parade à la Foire au pain d'épices), ca. 1900. Stereoscopic-format postcard. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

You will also have to visit the exhibition to watch the film footage we found of a British sideshow in the 1890s––a crowded and raucous affair, so different from Seurat's picture but in the spirit of what he witnessed at the Gingerbread Fair. In 1898, American tourist Ernest R. Holmes concluded that "rollicking merriment, with some degree of license and lewdness, makes the Gingerbread Fair one of the most characteristic exhibitions of the Parisian childlike fondness for amusement."

This documentary evidence of the actual event Seurat depicted in Circus Sideshow underscores the inventiveness of his approach. Through his Neo-Impressionist technique, he achieved what Charles Baudelaire proposed in 1863 as the aim of the "Painter of Modern Life"—"to distill the eternal from the transitory," elevating a very timely subject to timeless status.

After you get a "taste" of the Gingerbread Fair in the exhibition, stop by the adjacent cafeteria, where Met Dining is offering special packages of pain d'épices and other circus-themed fare. And for those interested in further research, we have included an illustrated checklist of the exhibition, including all of the ephemeral material.

Related Links

Seurat's Circus Sideshow, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through May 29, 2017

In Circulation: "Side Notes on the Sideshow" (April 5, 2017)