Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). Camille Claudel au bonnet (Camille Claudel with a Bonnet), 1884. Plaster, 10 x 6 x 7 1/4 in. (25.3 x 15.2 x 18.5 cm). Musée Rodin, Paris, France (S.01140). © Musée Rodin

«While it may not surprise you to learn that Auguste Rodin sculpted more than 100 portraits, would you have guessed that the granddaddy of modern sculpture made the majority of these portraits at his own request? His sitters, often people close at hand, ranged from personal muses like his wife, Rose Beuret, and the sculptor Camille Claudel (with whom he was romantically entangled), to dancers, writers, and musicians. That his inspirations often came from the performing and fine arts is not surprising, as this larger artistic domain was his ecosystem in the world. And yet, his choice of subjects raises a question: what inspires sculptural creativity?»

Rodin began making portraits, as so many artists do, for financial reasons. After his retrospective at the Place de l'Alma, Paris, on the occasion of the Universal Exposition of 1900, the sculptor received numerous commissions for portraits. Then, late in life, he churned out many portraits of members of high society—what we art historians call "society portraits." While portraits made him financially independent, he also found them to be an arena in which he could experiment. Commissions did not supplant his portraits of friends and fellow artists, and it was in his busts of those in the artistic communities close to him that Rodin was likely to go beyond the limits of traditional portraiture toward new, experimental approaches to the form.

Left: Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). Mask of Rose Beuret, ca. 1880–82 or 1898. Cast plaster, 10 11/16 x 6 3/8 x 6 5/8 in. (27.1 x 16.2 x 16.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Foundation, 1984 (1984.364.10). Right: Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). Rose Beuret, ca. 1898. Marble, 20 1/4 x 16 1/8 x 15 in. (51.5 x 41 x 38 cm). Musée Rodin, Paris, France (S.00987). © Musée Rodin

Rodin's Mask of Rose Beuret depicts the woman who stood by him from his early days as a starving artist to later years filled with infidelity. Though together for 53 years, the two only married in 1917, just before they both died. An illiterate seamstress whom Rodin met in 1864 when she was just 20 years old, Rose Beuret continued working for years to supplement the sculptor's paltry wages, even as she bore his son and modeled for him at night. While she has been called jealous and quick to anger, this late portrait of Beuret betrays neither of those traits.[1] Quiet and contemplative, Beuret is presented here with eyes downcast and mouth and cheeks calmly at rest. This depiction was transformed into his atmospheric and highly modeled marble Rose Beuret (from around 1898, in the Musée Rodin in Paris), with deep recesses of shadow and protrusions filled with light.

Right: E. Graffe and A. Rouers. Portrait of Rose Beuret (detail). Aristotype test on collodion mat, 5 1/2 x 4 in. (14 x 10 cm). Musée Rodin, Paris, France (Ph.1443). © Musée Rodin

The Met's portrait mask also shares much with Rodin's portrait of his mistress Camille Claudel au bonnet, and the similarly meditative sculpture for which she posed, La Pensée (marble versions are in the Musée d'Orsay, Musée Rodin, and Philadelphia Museum of Art, and a single posthumous bronze cast is in Philadelphia's collection as well). It might seem from these busts that Rodin treasured tranquility most in a mate; however, if Claudel had been at all calm in her earlier days with Rodin—most reports found theirs to be a stormy affair—we know this trait was lost, for the most part, by 1905 and her later years of mental illness.

Rodin's two busts of Mrs. Russell (née Mariana Mattioco della Torre), also on view in Rodin at The Met, portray the blonde Italian model who married the Australian painter John Pole Russell the same year that Rodin modeled her silvered bronze bust. The Russells were friends to Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters—among them Monet, Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Toulouse-Lautrec—and probably met Rodin through Monet and his friend, the writer Gustave Geffroy.[2] Both busts present a more conventional approach to portraiture often found in Rodin's images of women.

Left: Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). Mrs. Russell (Mariana Mattioco della Torre), modeled 1888, cast 1979. Silvered bronze, black marble base, 13 7/8 in. (35.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Foundation, 1986 (1986.37.3). Right: Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). The Head of Mrs. Russell, modeled ca. 1890, cast before 1912. Cast plaster, 10 7/8 in. (27.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Auguste Rodin, 1912 (12.12.6)

The focus is on conveying Russell's classical profile with a long, straight nose. The sitter was known for her great beauty and clear complexion; the silvery tones of the bronze make her skin catch the light, as it did in nature. While it is unclear whether the busts were part of a commission or not, it may well be that Rodin asked to make her portrait because he was so taken with her angular features. Her features inspired him to ask her to pose for sculptures of ancient deities Ceres, Minerva, and Athena. Rodin visited with the Russells often at their home at Belle-Ile on the Channel coast; he also bought paintings by John Pope Russell. The Russells particularly liked the silvered bronze version of her portrait for the way it showed every subtlety of Rodin's hand—for example, the stray strands of hair on her forehead.

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (French, 1824–1898). The Allegory of the Sorbonne (detail), 1889. Oil on canvas, 32 5/8 x 180 1/4 in. (82.9 x 457.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929 (29.100.117)

When Rodin modeled the portrait of his good friend Pierre Puvis de Chavannes around 1890, Puvis was already a famous painter. Known for his representations of antiquity and allegorical presentations of abstract subjects, as in The Allegory of the Sorbonne, Puvis probably first met Rodin in the 1880s. Together with the painter Eugène Carrière and others, they formed the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1890 as an alternative exhibition space to the annual Salon. Rodin presided over a banquet for Puvis's 70th birthday in 1895.

In 1890, the French state commissioned Rodin to sculpt a bust of Puvis in marble for the Musée de Picardie in Amiens, for which he exhibited a plaster version at the 1891 Salon. It was well received there by critics but Puvis disliked it. At first, this Salon version had shown the painter with an open chest, but Rodin clothed the figure at the last minute, according to Puvis's request. Puvis expressed criticism to Rodin of what he saw as the anachronistic contrast between the very modern depiction of his beard (note the clumpy, nearly impressionistic take on the squared beard that was in fashion for late 19th-century distinguished men, and his big, floppy mustache) and the nude state of his chest, which was often associated with ancient Greek and Roman statuary.[3] The mottled surface of the added jacket and beard are a far cry from a more typically "finished"-looking portrait of the period.

Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, modeled ca. 1890, cast ca. 1910. Bronze, 21 x 20 x 12 1/2 in. (53.3 x 50.8 x 31.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Thomas F. Ryan, 1910 (11.173.8)

Rodin definitely embraced new approaches in this portrait of his friend. He described Puvis as looking like a medieval warrior fighting for honor. The high forehead, expressive eyes, and knit eyebrows all convey a part-philosopher figure with an uncompromising nature. Rodin said of Puvis, "To think that he has lived among us, to think that this genius, worthy of the most radiant epochs of art, has spoken to us!" Puvis's rejection of the sculpture greatly upset Rodin. He said, "Puvis did not like my bust of him, and it was one of the bitter things of my career. He thought that I had caricatured him. And yet I am certain that I have expressed in my sculpture all the enthusiasm and veneration that I felt for him."[4]

Puvis must have picked up on a sense of haughtiness of the figure, who looks down the prow of his nose while his neck elevates his head rather stiffly. He observed that the position of the head with a backward tilt gave him an arrogant look in a note to Rodin of May 16, 1891, but Rodin excused this positioning as having been an attempt to catch the light better.

Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). Madame X (Countess Anna-Elizabeth de Noailles), ca. 1907. Marble, 19 1/2 x 21 3/8 x 19 in. (49.5 x 54.3 x 48.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Thomas F. Ryan, 1910 (11.173.6)

As artistic experiments often go, Rodin's bust of Puvis left the sculptor frustrated. The same was true of his Madame X. A generic title often used by 19th-century artists when the sitter wished not to be identified, Madame X depicts Countess Anna-Elisabeth de Noailles (née Brancovan, 1876–1933), the daughter of a Greek princess and granddaughter of a diplomat and man of letters. An old friend of Rodin's, this poet and member of the Nouvelle Pléiade literary group was married to Count de Noailles but mistress to the French writer and politician Maurice Barrès.

By 1901, Rodin had thanked her for her gift of a book of verse, Le Coeur Innombrable (The Innumerable Heart), so their friendship dates at least from then. Most likely introduced by mutual friends, the writer Octave Mirbeau or the painter Jacques-Emile Blanche, their admiration for each other played out in a series of letters over a period of 12 years. They often dined together as well. Blanche wrote to de Noailles in 1903 to say that Rodin wanted to make a bust of the countess. Sittings for the bust probably began in late 1905. The painter Edouard Vuillard recounted that she was a difficult subject who failed to keep her sitting appointments.[5]

Left: Studio G. L. Manuel frères (French, 1913–1939). Portraits of Countess de Noailles (Anna de Noailles Dornac) (detail), 1922–3. Album of 135 photographs, various techniques, 16 1/8 x 12 1/2 in. (41 x 32 cm). Bibliothèque national de France, département Estampes et photographie (National Library of France, Prints and Photographs Department). Image via Wikimedia Commons

In the end, de Noailles rejected the portrait because she did not like the representation of her nose. From photographs of her, one can see that the prominent, crooked nose was true to life and Rodin refused to change it, saying, "Otherwise, she was a very intelligent person."[6] In this bust, as in so many of Rodin's late portraits of women, the sculptor worked in marble because of the medium's possibilities of softer, scrim-like formal effects. Madame X appears to us as if seen through a mist; with slits for eyes, she appears to be in a tranquil dream state. (Again, Rodin sought out an image of tranquility in women.) The sculptor harnessed light to create a sense of a luminous haze around the figure, as if her face could not be separated from the atmosphere that surrounds it. With the rough marble base against her smooth face, she appears remote and introspective.

By 1908, the countess asked Rodin not to exhibit the sculpture, saying that her features were not yet fully transmitted into marble. She would not acquire it, but she also did not want him to sell it; she called it only a sketch. When Rodin suggested retitling it Jeunesse de Minerve (The Youth of Minerva) so that he could sell it, she refused, saying the piece was much too precise to be labeled Minerva, or even any sort of generic personification of a Greek or Roman god. Their dispute landed in the press in 1910, and when Thomas Fortune Ryan offered to buy the work for The Met that year, Rodin asked her permission. There is no record of her response, but he sold it the next day. Throughout this period of dispute about the sculpture, Rodin and the countess kept up regular lunch dates.

Meanwhile, Blanche suggested that the countess not let it be known Rodin had asked to do her portrait, as Rodin was only just gaining international recognition for society portrait commissions. (It was more prestigious to have a countess come to an artist and ask for her portrait than for the artist to beg to do it.) Soon enough, though, to have one's portrait done by Rodin became sought after from just such busts; it didn't hurt Rodin among American patrons, for example, that de Noailles's portrait landed in The Met collection in 1910.

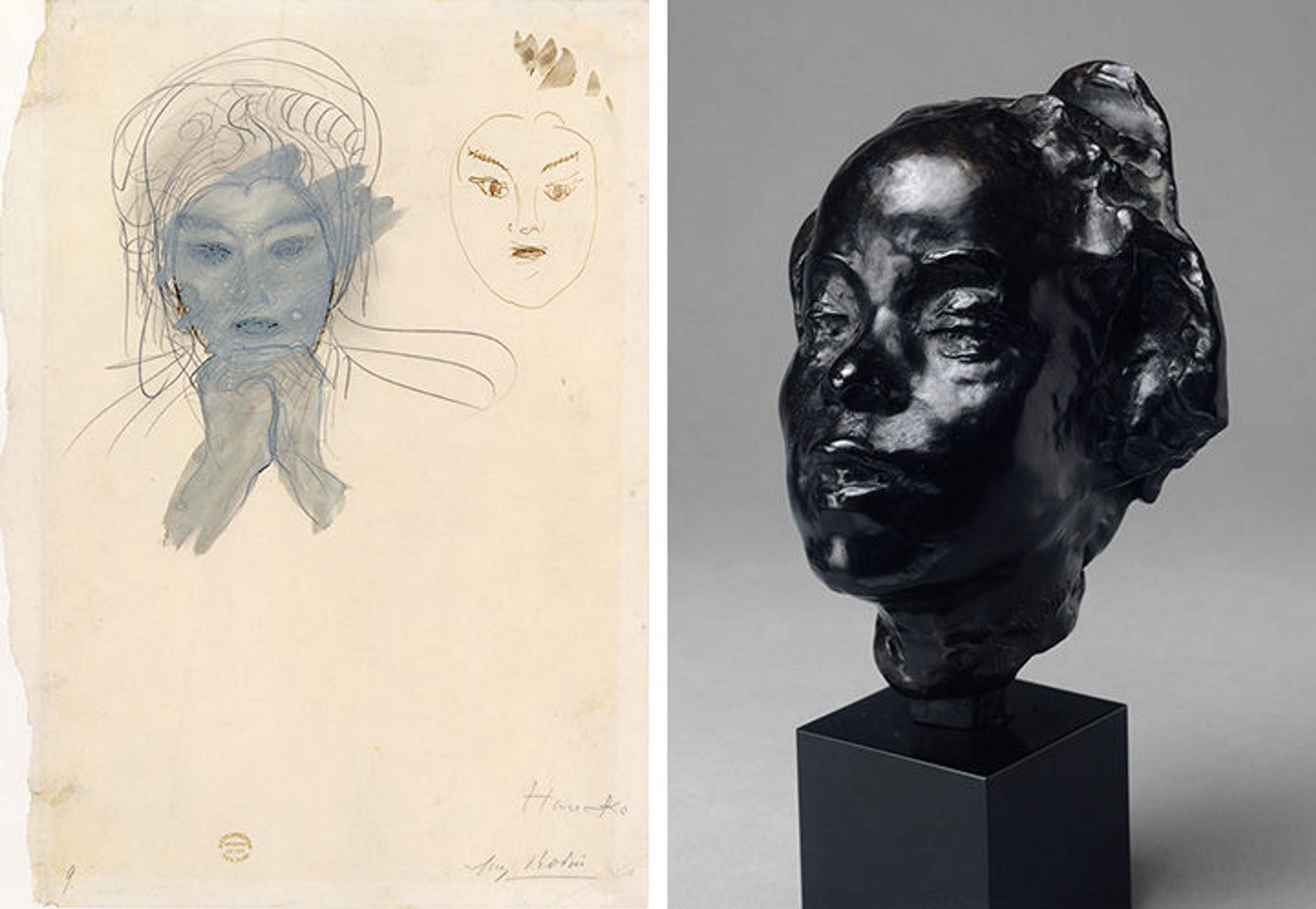

Left: Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). Hanako, 1907. Graphite, pen and brown ink, gouache-wash, and red crayon, 11 3/4 x 8 7/16 in, (29.9 x 21.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1910 (10.66.2). Right: Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). Mask of Hanako (Ohya Hisa, 1868–1945), modeled 1908, cast probably before 1950. Bronze, black marble base, 6 x 4 1/2 x 3 3/4 in. (15.2 x 11.4 x 9.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Foundation, 1984 (1984.364.4)

Finally, the Mask of Hanako (Ohta Hisa, 1868–1945) and the related drawing from the previous year portray a Japanese dancer and actress whom Rodin encountered in 1906 in Marseille, where he had gone to study the Royal Cambodian Dancers. He was introduced to Hanako ("Little Flower") by his friend, the American modern dancer Loie Fuller. Hanako had been touring Europe since 1900, and Fuller acted as her agent. The dancer was known for her ability to hold difficult positions for a long time. She posed for Rodin, and he made 53 heads and many drawings of her. Rodin's biographer and friend Judith Cladel described Hanako's posing sessions with Rodin:

Hanako did not pose like other people. Her features were contracted in an expression of cold, terrible rage. She had the look of a tiger, an expression thoroughly foreign to our Occidental countenances. With the force of will which the Japanese display in the face of death, Hanako was enabled to hold this look for hours.[7]

Right: Portrait of Hanako. Silver gelatin print, 7 1/2 x 4 3/4 in. (19 x 12 cm). Musée Rodin, Paris, France (Ph.193). © Musée Rodin

Rodin captured her agile face and sometimes-extreme expressions. He was fascinated by the mobility of her facial features and their ability to represent joy and anguish. While the gouache drawing of Hanako with her hands at her chin shows her face at rest, much like the related drawing in the Musée Rodin, both the mask and the image of her face at right in The Met's drawing show Rodin unafraid to investigate her ability to maintain long poses, for example with eyebrows raised and mouth taut. In these, we see that he veered away from traditional images of beauty in some women, at least, even if he did not dare test that tactic in his portraits of European and American society women.

Rodin's exploration of portraiture was always in the service of Nature, to whom he committed to be "servilely faithful."[8] That some of his sitters could not abide Rodin's version of truth to Nature left the artist unfulfilled and, at times, exasperated. His late turn toward performers like Hanako and, in the same period, Vaslav Nijinsky may well have been an attempt to sidestep traditional societal norms for portraiture when working for himself. So, what so often inspired Rodin's inventiveness when it came to portraiture? Other artists and their own creative forces.

Notes

[1] Joan Vita Miller and Gary Marotta, Rodin: The B. Gerald Cantor Collection (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986), 103.

[2] Ibid, 104.

[3] Letter from Puvis de Chavannes to Rodin, March 23, 1891, Puvis de Chavannes curatorial file, Archives, Musée Rodin, Paris.

[4] Auguste Rodin, Rodin on Art and Artists: Conversations with Paul Gsell, trans. Romilly Fedden (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1983) [Translation of Rodin, L'Art, ed. Paul Gsell (Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1911).], 58.

[5] Clare Vincent, "Some European Portrait Sculpture," The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 24, no. 8 (April 1966), 249.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Judith Cladel, Rodin: The Man and His Art, with Leaves from His Notebook, trans. S. K. Star (New York: Century Co., 1917), 162.

[8] Rodin 1983, 11.

Related Content

Read a blog series on Rodin at Now at The Met.

See more digital content related to Rodin at The Met.