Mary Beard and Julia Siemon in the Greek and Roman galleries at The Met

«What happens when masterpieces of Renaissance silver are taken apart, put back incorrectly, then scattered around the world? I recently sat down with Cambridge classicist Mary Beard and Assistant Research Curator Julia Siemon in the audio studio at The Met to chat about the exhibition The Silver Caesars: A Renaissance Mystery. Mary had just flown in to record a soundtrack for a set of videos to accompany the exhibition, and Julia was preparing the installation.

It's no surprise that Mary, a renowned Roman historian beloved for her BBC series, her regular column in The Times Literary Supplement, and her work on Roman literature and culture, should be asked to comment on imperial imagery. But images on Renaissance cups?» As it turns out, however, these are no ordinary cups, as she is no ordinary reader.

Over the past few years Mary has decoded the images on the silver cups, reading their intricate stories with the same keen eye with which she reads Latin texts. Meanwhile, Julia has used her expertise in Renaissance art to clear up centuries of scholarly perplexity about when, where, by whom, and for whom the cups were made. The fruits of their work are on display at The Met through March 30 and in the publication that accompanies the exhibition.

In the first part of this interview, Mary and Julia describe their initial encounters with the tazze and take us on a walk through the major themes of the exhibition, showing us what to look for in these masterpieces of Renaissance art. In Part Two, they explore the relationship between the silver images and the racy Latin text they illustrate in an effort to understand how viewers could ever have misread the stories on the cups and so badly mixed them up.

Sumi Hansen: Mary, you've come to The Met today to record a soundtrack for two videos about the Renaissance cups known as the Silver Caesars. What is the mystery, and how do the videos help dispel it?

Mary Beard: I think most people gain some sense of how to look at a painting, but no one ever teaches you how to look at a piece of silver. Until recently, when I saw bits of silver in a museum, I'd say, "How lovely," and walk quickly past. But the Aldobrandini Tazze are the greatest jigsaw puzzle on earth. They're better than the thousand-piece jigsaw you do at Christmas—the pieces are not even on the same continent! So the mystery associated with them has done the silverware a good turn, because it's a point of entry. You say, "Hey, there's a puzzle here." That's what gets you in. Then you start to think, "This silverware is really interesting." That's when you start to really look at it. That's where the videos come in.

Installation view of the Domitian tazza

Sumi Hansen: When did you first get interested in the tazze?

Mary Beard: I'd gone along to the V&A [the Victoria and Albert Museum in London] to see a silver bowl with a figure. It was a figure of the Roman emperor Domitian on a bowl parading images from his life. I thought, "I know all these images come from the Latin author Suetonius, so I'll just take my copy of Suetonius with me to kind of match up the details."

Everyone at the museum was terribly welcoming. They put their gloves on. They started unscrewing the emperor. Suddenly the whole thing was in bits all over the place. I thought, "Wow, I didn't know silver was like that!"

Detail from the Tiberius tazza

Before he turned to drive up onto the Capitoline Hill, he got down from the chariot and dropped to his knees in front of his father [the emperor Augustus], who was presiding over the ceremony. —Suetonius 20

They were all busy with their silver, so I got my Suetonius out and started to try and match up the scenes. But the more I looked at them, the more they didn't match. I saw a wonderful image of a triumphal procession on the bowl, a great celebration: the emperor going along, celebrating his victory, with troops behind. It was (according to the catalogue) the triumph of the emperor Domitian. I looked at this and I thought, "This is odd." Because when you looked closely, the emperor, if he was in the chariot, wasn't in the chariot any longer! Whoever it was celebrating his own victory had got out of the chariot—the chariot was empty—and was kneeling in front of somebody else. Now, I know enough about the triumph to know that's not what happens in a triumph. I thought, "That's odd."

Suddenly I had a vague recollection of an unusual event in the triumph of the emperor Tiberius, before he was emperor. Tiberius has won his victory. He is having his procession. But before he goes up to the Capitoline Hill in Rome, he gets out of the chariot (says Suetonius) and kneels in front of the emperor Augustus, his adopted father, to show his respect. I thought, "That's got to be that moment!" In which case, I realized, the scenes on this bowl are not illustrating the life of Domitian, they're illustrating the life of Tiberius.

Suddenly you look at every other scene on the bowl and you see that, however much people have tried to massage them into being from the life of Domitian, they're actually all from the life of Tiberius. I felt, frankly, kind of pleased with myself—frightfully cocky about it! But it didn't take long to wonder, "If this is Domitian on the bowl of Tiberius, well, where's the bowl of Domitian? and where is Tiberius?" At this point, all the dominos started to fall. Of course, I hadn't been entirely the first person to see some problems here.

Sumi Hansen: The tazza you were looking at that day—wasn't it the result of a previous attempt at matching?

Mary Beard: It was. The poor old V&A. There was a three-way swap with The Met and the Royal Ontario Museum.

Julia Siemon: The V&A had the figure of Otho on what they thought was the bowl of Domitian. It was a very reasoned decision! The curators had traced the bowl back to a sale in 1893 where it had been identified as Domitian. So they wanted to restore the figure of Domitian to his bowl. But the identification was wrong, and they restored a mistake.

Mary Beard: They were so pleased with themselves. What a forward-looking thing to do! Here were three pieces all mixed up, and these three forward-looking museums were going to swap the figures around so everything was going to go back to be fine. Fine for The Met, since they did get a bowl and matching figure, and fine for the Royal Ontario Museum, but . . .

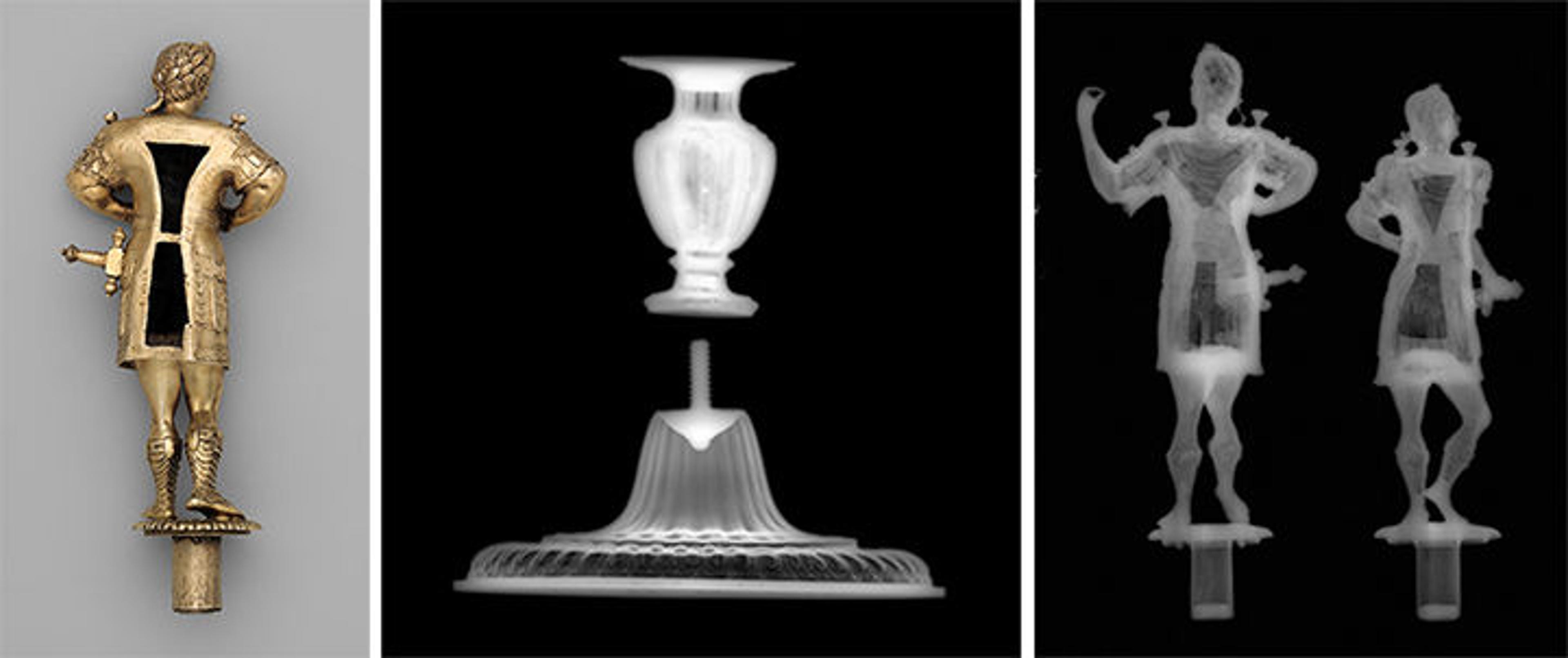

Left: Figurine of Tiberius, reverse. Center: Radiograph of original foot of Tiberius figure tazza. Right: Radiograph of Caligula (left) and Claudius (right) with capes removed

Sumi Hansen: Julia, when did you first see the Aldobrandini Tazze?

Julia Siemon: I had a similar experience to Mary, a few years later. One day Ellenor Alcorn, the curator in charge of silver at The Met, reached out to me and said, "We have this project. We think you might be interested in it. Would you come have a look?" My specialty is Italian Renaissance painting. So in reading the email, unfortunately, I had exactly the same response as Mary. I said, "What? Silver cups? It can't be anything relevant to me, but who knows?" And I agreed to come and look at them. So Ellenor picked up a dog-eared copy of the Robert Graves translation of Suetonius and we went downstairs to Objects Conservation.

This visit aligned with a wonderful moment in 2014 when The Met was able to bring all the tazze here to the Museum. All twelve were in Objects Conservation that day—the first time they had been together since the 1860s. Ellenor and I sat down and took turns reading the stories. We went through and made a list of what we thought was happening, saying, "Wait, I see that! Wait, I see that!" Then we started emailing back-and-forth with Mary. And I had a similar experience—I fell in love. I absolutely fell in love, and it completely changed my life. I took on this project full-time and have spent the last three and a half years devoted to it.

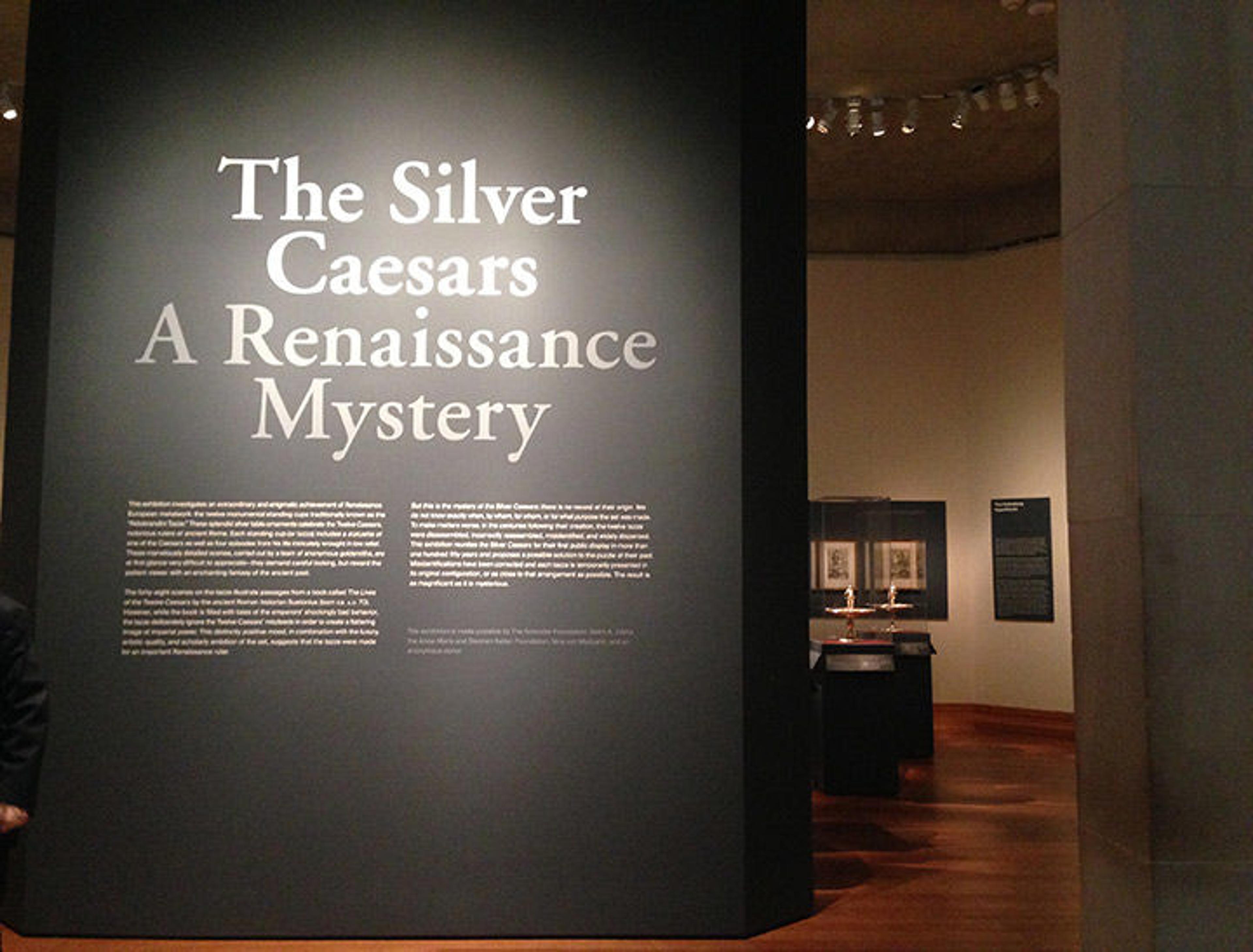

View of the entrance to the exhibition

Sumi Hansen: The tazze are being united at The Met again this year. What's special about seeing them in the context of the exhibition? How does it illuminate the story behind the objects?

Julia Siemon: Well, this is a tricky show. The tazze are hard to look at, but they reward the careful viewer. I had to think hard about what stories I want to tell. The exhibition accomplishes several things. First, we're going to show people some of the best early modern silver existing in the world. Not just the tazze, but the loan pieces as well. We sometimes mistakenly dismiss silver as simply something you'd eat off. But silver was used in the Renaissance as a medium suitable for the highest levels of artistic ambition, intellectual ambition, and political statement. These pieces were viewed as objects as important as any major tapestry cycle or painting cycle—if not much more so, actually. So that's one story.

Another major story is, "Hey, look at what The Met was able to do! Not only were we able, in cooperation with our collaborators and lenders, to reidentify the tazze and solve that mystery, but we've brought them all together for this brief window of time. And not only are we bringing them together, but we're also taking them apart and displaying them correctly."

But it's not just that we've reidentified and reunited these objects. It's also that The Met's talented photographers took pictures of the tazze. I can't stress enough how I believe these stunning photos will serve the study of Renaissance silver. We now have beautiful digital photography of objects that are very hard to look at and that are not even in the same place. So I think we have to be careful about being too patronizing of people who've made mistakes with the cups in the past, because they literally didn't have all the objects to look at. The cups were all over the world—

Mary Beard: It's very generous of you.

Julia Siemon: I have to say! And even when people did have pictures, the cups are hard to follow. They're concave, they're shiny—

Mary Beard: I'm less generous, actually. I have to say! I think all you needed was a copy of Suetonius, and you just needed to read him.

Julia Siemon: It's true.

Installation view of the exhibition, with Caligula tazza in foreground

Sumi Hansen: Julia, can you walk us through the exhibition? What will we see, Suetonius in hand?

Julia Siemon: The exhibition has three thematic sections. When viewers come in, they see a diagram so they can understand what they're looking at. Then the first story, "The 19th Century Invents the Renaissance," starts with a problem: yes, we're calling them the Silver Caesars, and yes, they're made out of silver, but they look gold! That gold was added in the 19th century. This area deals with the fact that there were interventions in the 19th century that changed the way the tazze look.

The next area is "The Renaissance Invents Ancient Rome." How did the Renaissance see ancient Rome? How did they know what stories to tell and how to tell them? How did they investigate and reconstruct?

Right: Aureus of Claudius showing a military base, A.D. 44. Rome. Gold, 18.5 mm, 7.05 g. American Numismatic Society, New York, E.T. Newell Bequest (1944.100.39353)

Here I gather together examples of the kinds of source materials that were used to create the ancient scenes on the tazze. These objects could not have been created without some incredible intellectual mind that knew not only Suetonius but also the other ancient materials that illuminate the stories that Suetonius tells. This was not someone wandering the streets of Rome; it was someone who had access to visual representations, studies of the ancient past, portable antiquities, and, in particular, coins. Coins offer incredibly concise emblematic images that are really weighty with their iconography. Because what we're looking at in the cups isn't ancient Rome! We're looking at another historical moment's reimagining, a kind of fantasy of ancient Rome, pulled out from coins, relics, and prints.

The final part of the show is what I'm calling "The Habsburg Hypothesis." Here I offer a number of reasons to think that the tazze were made at the end of the 16th century in the Habsburg Netherlands as a celebration of imperial power.

Mary Beard: Another mystery! We're claiming it's a great work of art, but in terms of straightforward evidence we don't know where they were made, or who they were made by, or who they were made for, or why, or when. The jigsaw puzzle mystery gets you in. Then you discover that every single aspect of their history is mysterious. Julia's done a pretty damn good job at narrowing down the possibilities.

Julia Siemon: I don't want people to come in and say, "Yes, I agree with the Habsburg hypothesis," or, "No, I don't agree." What I want them to see is, "Oh! Here are other objects that work in much the same way!"

Left: Artus Claessens, 1625–1644. Still life with a Silver-Gilt Tazza Surmounted by a Personification of Painting. Antwerp. Oil on panel, 79 x 40.5 cm. Private collection, Amsterdam. Right: Elias Marcus and Jeremias Maes. Breda cup (Schale), showing the liberation of the town of Breda in 1590. Breda, 1600. Gilded silver. Hohenlohe Museum, Neuenstein Castle, Germany

We're getting a fabulous basin from the Louvre that was created for the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor Charles the Fifth. This object was covered in low-relief scenes in an ancient style to commemorate a military victory he had 20 years earlier. Again, it's ostensibly a dining form, but it's not for eating—it's a major silver gift commemorating a historical event and stylistically as close as anything to what we see on the tazze. There's also a standing cup with a cover, made in 1600, also in the southern Netherlands, that also commemorates an earlier battle earlier using print sources to tell the stories. So the Habsburg hypothesis is not a yes-or-no proposition; rather, it's "Look at how important silver is and what kinds of stories silver can tell."

Finally, I also have to address the fact that these objects are traditionally called the Aldobrandini Tazze. There is a coat of arms with an ecclesiastical element that appears on six of the dishes. (Of course, it can't be all twelve, it has to be six. Just to keep things interesting, right? Another mystery.) When the tazze appeared in 1826 on the British art market in London, seemingly out of thin air, the dealers who looked at them said, "Ah! An Aldobrandini coat of arms with a cardinal's hat. This must be the most famous Aldobrandini, Pope Clement the Eighth!" And then, "They're Italian Renaissance silver made for a pope, so they must have been made by Benvenuto Cellini," who had of course long been dead by the time Clement became pope.

In the Renaissance, ancient imperial Rome was used as a parallel to support imperial power in the Holy Roman Empire. In the book, I consider whether the tazze might have been made for the Archduke Albert VII of Austria. Regardless, the simple fact is that the Silver Caesars operate in a positive mode, celebrating imperial power. Whatever the origin of these cups, they're a very interesting way to think about art and power.

I also address the collecting history, as another chapter in the lives of these objects. Who would have wanted to own them? Why would you want to own them? What would you do with them?

Mary Beard: It is very interesting that they go all over Europe. They probably start in the Low Countries, then they go to Italy, to Paris, to London. That's how difficult these art objects are to pin down. They're mobile! They're split up! They're not just split up because they somebody decides to unscrew Domitian—they're disaggregated. That history of recombination and separation is itself really interesting.

Julia Siemon: By the end of the 19th century, they were owned by some of the most well-known collectors. The Rothschilds owned probably five of them; Hearst had one; Morgan had one. They were passed around among the top collectors—and, frankly, that's still the case. The Met's came to us because of a collector, and a viscount gave the one to the Royal Ontario Museum. So an interesting facet of the story is that these tazze came from major collections and are still seen as worthy of the world's most famous collectors.

Sumi Hansen: When American viewers see the Twelve Caesars, they may think of the nice orderly progression of presidents with their four- to eight-year terms . . .

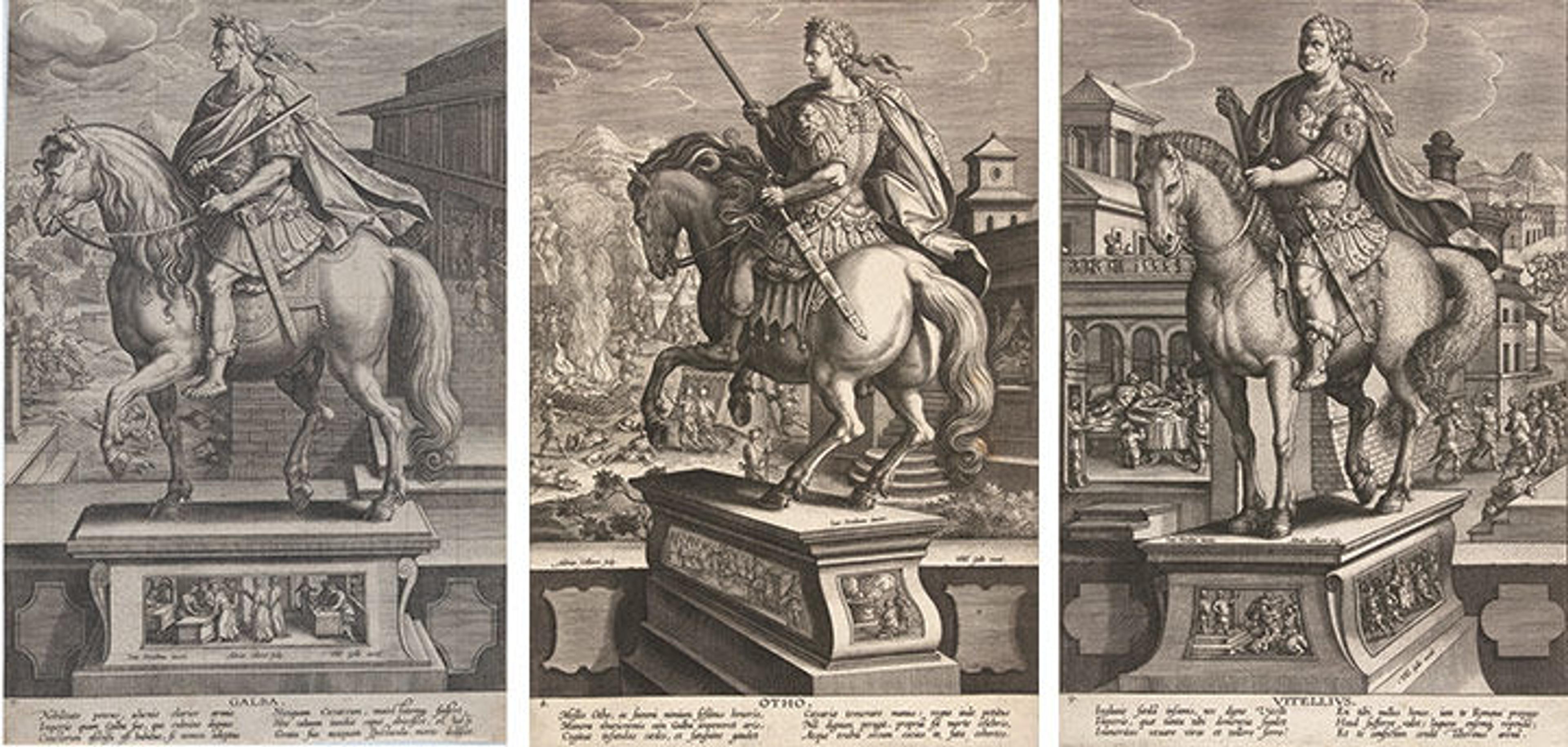

Adrian Collaert (Netherlandish, 1560–1618). From left to right: Engravings of equestrian statues of Galba; Otho; Vitellius, from Roman Emperors on Horseback, 1587–89. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1949 (49.95.1002[7, 8, 9])

Julia Siemon: This is a huge problem. I was just thinking about this today. I'm working on interpretive texts and polishing up my labels for the gallery. We are showing a set of twelve portrait prints of the Caesars. Fine! Now, because we're not lining up the Silver Caesars but putting them in individual vitrines in a stack in the center of the room, I'm using this series of portrait prints as an opportunity to create a timeline in the gallery, starting with Julius, then Augustus, and so forth. However, when I put the date on the prints, I'm putting the reign date. So in the center of this timeline there are a bunch of them that say "69"! [laughter] I am totally baffled at how I'm going to convey to the viewers the meaning of that random number, which doesn't look at all like a reign date of any kind, since it doesn't indicate a span.

Sumi Hansen: So, Mary, what in heaven happened in that year?

Mary Beard: Mayhem! [laughter] You're absolutely right; there is a problem. I suspect that quite a lot of people will imagine that it's much more formalized, like four to eight years of a president.

What you've basically got is this. We have to thank Suetonius for the whole idea of the Twelve Caesars. If it wasn't for the fact that Suetonius wrote twelve biographies of the first twelve emperors of Rome (and even that is quite tricky), that kind of magic number would never have come down to us. It was a literary category, but never a visual one. Apart from Suetonius, you can't go to any Roman work of art at all and see the Twelve Caesars. It is almost entirely a modern category that we find in the tazze, in prints, and in all kinds of paintings. A wonderful attempt to systematize what's a real mess.

To say "Who were the first emperors of Rome?" is difficult even at the very beginning. If you were to ask most people studying classics who was the first, they would not say "Julius Caesar," they would say "Augustus." Suetonius is offering a different version of that. He's saying, "Look, if you think about imperial power, it starts with that guy Julius who never called himself an emperor but who calls himself a dictator and was assassinated." It's already a big decision—and one not normally followed—to call Caesar the first emperor.

But the Roman Empire had amazing longevity. In establishing its basic principles and how it worked politically, Augustus (much more than Caesar) invented a system that lasted for hundreds of years. This is where the whole issue about succession becomes very funny. The one thing that Rome never worked out was how power was to be passed on from one man, one sole ruler, to the other. Most European monarchies assume—happily in America you don't have to think about this!—that it's the eldest son. But there is no rule in Rome that says the person who succeeds one emperor when he dies is his eldest son. It helps to be the eldest son. It's quite a good start. But it's not sufficient condition.

Inscription on the Galba figurine, upper disk

Sumi Hansen: Does the strangeness of the year 69 show up at all in the cups? Are the images different? More generic?

Mary Beard: No. Really interesting! If you were to look at the cups, you wouldn't be able to tell that there were these poor old three in the middle that didn't make it; they're treated just like the others.

Julia Siemon: Exactly the same treatment. Galba is full of succession pictures. Galba is fascinating in that the whole thing is about good omens and good predictions, and I suppose he did become emperor for a minute. There's even a scene of literal succession where he's choosing his successor. But it doesn't work out! They both get murdered.

Mary Beard: So what you see in the cups, nicely massaged and made to look completely normal under the title of Twelve Caesars, is a whole series of difficult and contested successions of power from one generation to the next—often helped by murder and assassination—with an intermezzo of a brutal year of civil war with emperors that now most people haven't heard of. So, even within these first twelve Caesars that look as if they're a very nice and neat set, people will come and look and say, "Vitellius? Who's he?" If you were to go out into the street and ask people about Nero, you would get name recognition. But Otho? So you've got a mess of war-contested succession, bits of hereditary succession, new dynasties, etc., all frightfully confused underneath this title of Twelve Caesars.

Sumi Hansen: What will happen to the cups after they leave here? Any chance that Julius and the eleven emperors can stay matched with their stories, or will they be jumbled up again and sent home?

Figurines of the Twelve Caesars, ca. 1575. Silver gilt, each 15 1/2 in. (39.4 cm)

Julia Siemon: They will! They arrive at the Museum in their mismatched Frankenstein states. We take them all apart and install them correctly reassembled. This is a wonderful privilege for which we are incredibly indebted to the lenders, but a logistical nightmare—lots of tagging and stickers! I actually had a moment of panic recently trying to figure out if we could make them all face the same direction in the installation, or if it was going to look like they were at a garden party. [laughter] Anyway!

When the exhibition is over, we can't ship the temporarily reassembled objects. So we take them apart and restore their historic misalignments, then ship them to England for the second venue at Waddesdon Manor, where they will again be taken apart and correctly put back and installed. When that show closes, they will be taken apart one more time, put back incorrectly, and sent home to their wonderfully generous and patient owners.

Sumi Hansen: I'm curious, wouldn't some of the lenders like to keep the correct configuration?

Julia Siemon: Indeed. There is great interest from some of the lenders, who think, "Gosh, why don't I just take home the right figure for my dish?" [laughter] But the question is, "Do you keep your dish? Do you keep your figure?" I think the answer is, "You keep your dish and the foot that goes with it." But the whole thing is very complicated. So there's interest from some of the owners in restoring the tazze to their original arrangements, but that is something that is being explored between the lenders. The Met is not involved in that process.

Note: This interview has been edited for publication.

Related Links

Now at The Met: "Decoding the Silver Caesars: A Conversation with Mary Beard and Julia Siemon, Part Two"

The Silver Caesars: A Renaissance Mystery, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through March 11, 2018

MetMedia: "The Nero Tazza"; "The Vitellius Tazza"