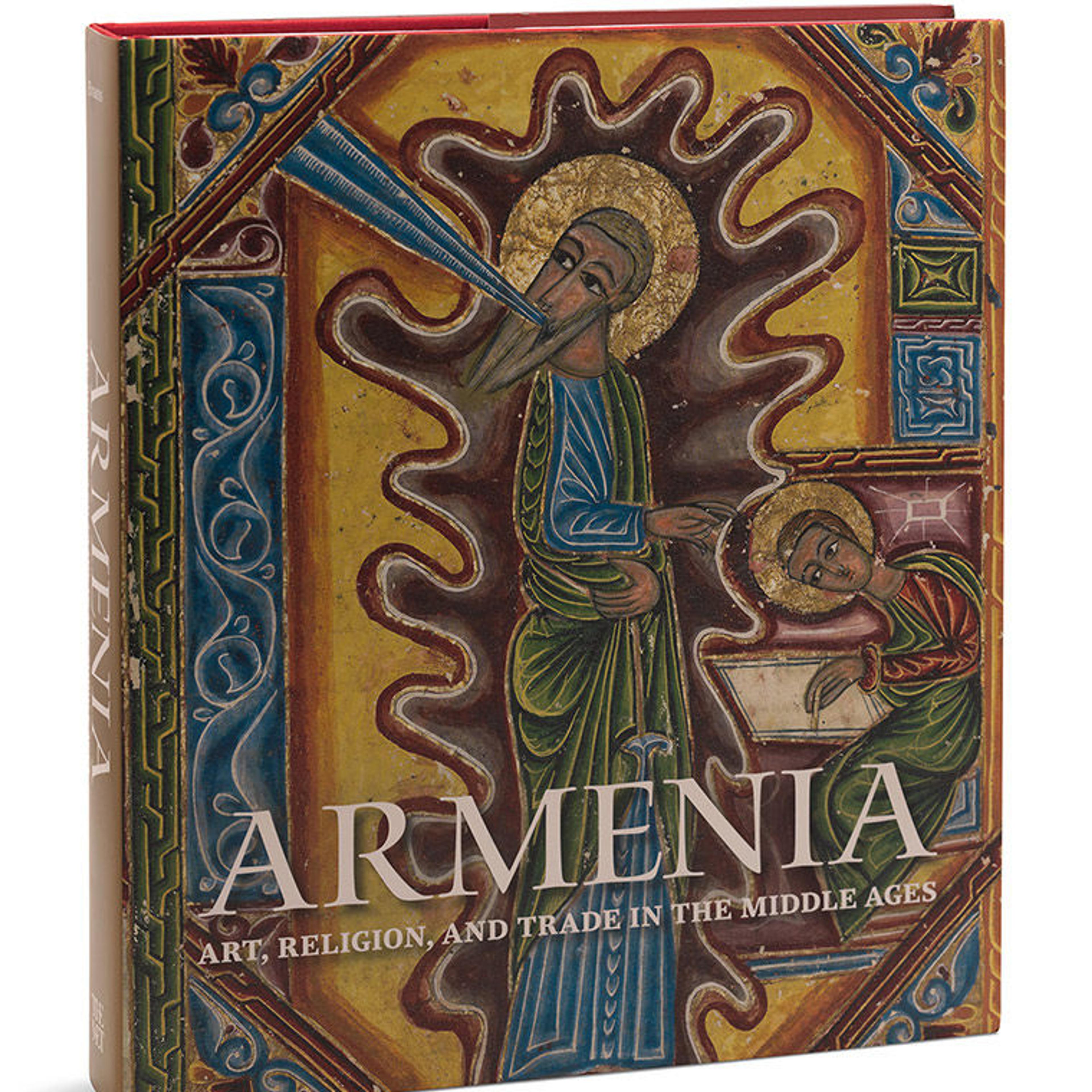

Armenia: Art, Religion, and Trade in the Middle Ages, edited by Helen Evans, features 282 full-color illustrations and is available at The Met Store and MetPublications.

At the foot of Mount Ararat, on the crossroads of the eastern and western worlds, medieval Armenians dominated international trading routes that reached from Europe to China and India to Russia. As the first people to convert officially to Christianity, they commissioned and produced some of the most extraordinary religious objects of the Middle Ages. An unprecedented volume, published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and accompanying the exhibition Armenia! (on view through January 13, 2019), addresses the rich cultural legacy of this often overlooked medieval community that interacted with Romans, Byzantines, Persians, Muslims, Mongols, Ottomans, and Europeans. With groundbreaking essays by international scholars and exquisite illustrations, Armenia: Art, Religion, and Trade in the Middle Ages illuminates the singular achievements of a great medieval civilization.

Helen Evans, the editor of the catalogue and curator of the exhibition, spoke with me about her long history studying this topic, the ways in which we might relate medieval Armenia to the present day, and why Armenia has been overlooked in the history of Christian art.

Rachel High: In your introductory essay you note, "Armenians served other states, often as soldiers and, at times, as rulers. Yet, while interacting with others, they retained their own identity." In other words, medieval Armenians were adaptable to changes in government, but also stayed true to their culture. How were these seemingly contradictory traits reflected in their aesthetic pursuits?

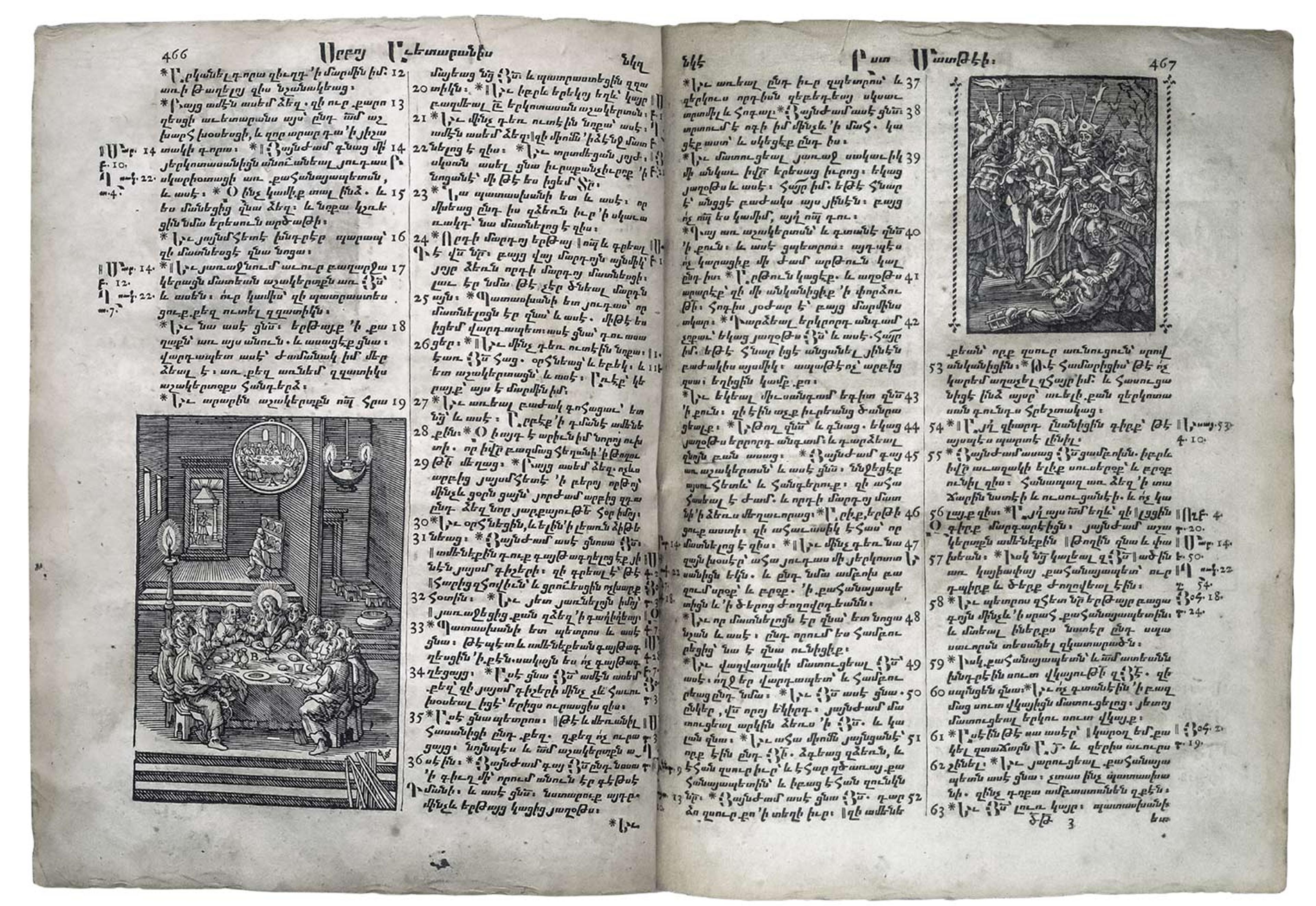

Oskan Bible, 1666. Edited by Oskan Erevants‘i (1614–1674); woodcuts mostly by Christoffel van Sichem II (Dutch, ca. 1581–1658). Printed in Armenian by Surb Etchmiadzin and Surb Sargis Zoravar Press. Made in Amsterdam. Ink on paper with gold-tooled leather binding, 10 5/8 x 8 5/8 in. (26.4 x 20.7 cm). Diocese of the Armenian Church of America (Eastern)

Helen Evans: I think that what to us appears to be a dichotomy would not have been perceived that way at the time. Armenian artists deliberately copied manuscripts from three or four hundred years earlier, but they also imported new, Western European imagery. This is particularly evident in the first bible printed in Armenian, the Oskan Bible, where you see the style of the past alongside new and innovative styles that reflected their contemporary world. The Armenians were of their day but also remembered their past, which isn't very different from what we do today.

Rachel High: I found the dual influences of West and East in Armenian works of art fascinating.

Antependium or altar frontal, 1695. Probably New Julfa. Silk with silver, and silver-gilded threads wrapped around a silk core, 39 x 87 3/8 in. (99 x 222 cm). Holy See of Cilicia, Antelias, Lebanon (1084)

Helen Evans: I'm not sure that medieval Armenians saw it that way. While installing the show, I found myself thinking that certain elements of a late seventeenth-century altar frontal from New Julfa looked Persian. But the Armenian artist was living in Persia! I don't think the artist made something that looked intentionally Persian. I think they just observed that people of affluence desired this type of visual treatment.

There's a wonderful quote from the twelfth century by Nerses of Lambron, a high-ranking official in the Armenian Church who had upset more-conservative prelates by adopting Western religious attire. He writes back to the King, declaring that he would dress as his ancestors did when the King stopped dressing like the French court and the people of greater Armenia went back to wearing traditional garments.

Today, whether you're an Armenian in New York, Paris, or Greater Armenia, you wear blue jeans. We don't question that. I do find some of the things we ask about the medieval world can be answered just by looking at ourselves—they were doing just what we are doing!

Armenians varied their dress depending on the context, just as most of us do today. These details of two manuscripts show Archbishop John from Cilicia wearing the French fleur-de-lis (left) and a dragon motif popular in Eastern Central Asia (right). The portrayal of these two different styles suggest Cilicia's role as a major conduit of trade between East and West.

Left:Marshal Oshin Gospel Book (detail), 1274. Sis. Scribe: Kostandin (act. 1274). Tempera, ink, and gold on parchment; 320 folios. 10 1/4 x 8 1/8 in. (27.5 x 20.5 cm); one leaf, 8 3/4 x 6 in. (22.2 x 15.3 cm). Manuscript: Morgan Library and Museum, New York, purchase by J. P. Morgan, Jr., in 1928 (ms M.740); leaf: Morgan Library and Museum, New York, purchased in 1998 with funds from: The Manoogian Simone Foundation; the L. W. Frohlich Charitable Trust, in memory of L. W. Frohlich and Thomas R. Burns, in recognition of the interest in and contributions to the arts of the written word; the Hagop Kevorkian Fund; the Fellows Acquisition Fund; Kaloust P. and Emma Sogoian; Antranig and Varsenne Sarkissian; an anonymous donor, in memory of Sirarpie Der Nersessian; and the Institute de Recherche sur les Miniatures Armeno-Byzantines (ms M.1111). Right:Gospel Book of Archbishop John (detail), 1289. Sis. Scribes: Archbishop John (Yovhannes; d. 1289) and an unidentified scribe. Ink, tempera, and gold on parchment; 353 folios. 10 1/4 x 7 3/4 in. (25.8 x 19.5 cm). "Matenadaran" Mesrop Mashtots‘ Institute-Museum of Ancient Manuscripts, Yerevan, Armenia (ms 197), fol. 341v

Rachel High: The book includes stunning site photography of Armenian architecture. How does a sense of place factor into the Armenian visual identity?

Helen Evans: Armenians originally settled in a highly mountainous area, and their architecture is just compellingly handsome in this landscape. I have described the churches with a central dome and faceted rooflines as like quartz formations growing out of the ground. Today, maybe even more than in 1500 A.D., Armenians use this architecture to identify themselves; you can go to Thirty-fourth Street and Second Avenue in New York to see a beautiful, forty-year-old church that is a variation of the Church of Saint Hripsime built in the seventh century in Armenia.

Church of Hripsime, 618. Etchmiadzin. Photo by Hrair Hawk Khatcherian, assisted by Lilit Khachatryan

Rachel High: You wrote your dissertation on Armenian art. What was it like to return to this subject that you pursued at the beginning of your career? What drew you to the topic in the first place?

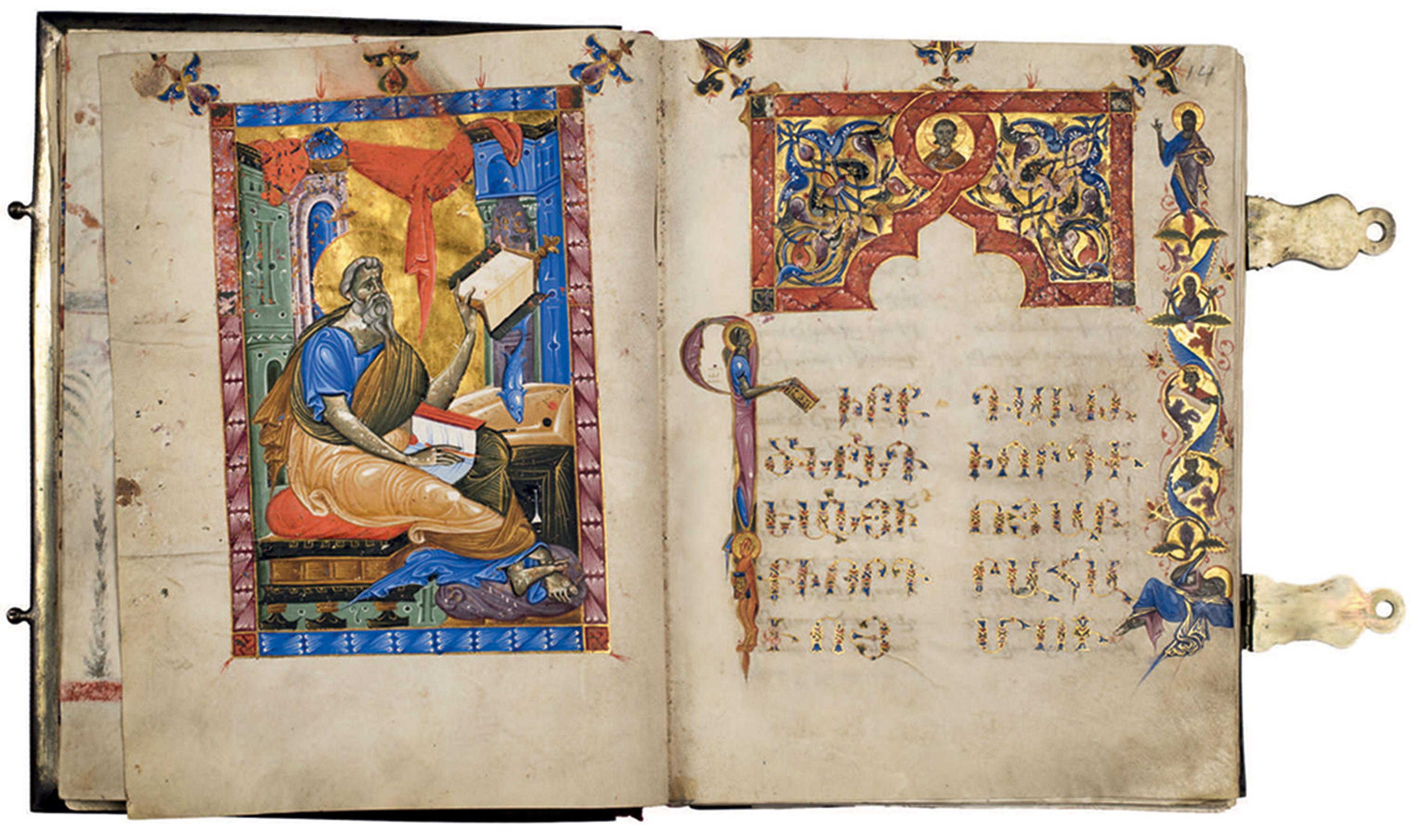

Helen Evans: It's a very exciting return to a field that I studied at the beginning of my career. My dissertation focused on the Armenian manuscript illuminations of their kingdom of Cilicia on the Mediterranean and in particular their connection to Western Europe. This was at a time when Armenia's connections to Western European were not widely recognized, so it was a ground-breaking effort.

Armenian manuscripts like the one show evidence of contact with European contemporaries. Gospel Book, 1272–78. Sis. Ink, tempera, and gold on parchment; 281 folios. 10 5/8 x 7 7/8 in. (26.8 x 20 cm). "Matenadaran" Mesrop Mashtots‘ Institute-Museum of Ancient Manuscripts, Yerevan, Armenia (ms 2629)

Returning to this topic in a broader way has been illuminating and exciting. When I was writing my dissertation I wasn't paying much attention to the Armenians in Isfahan, New Julfa, or Crimea. The catalogue looks at Armenian culture as a totality. I think the publication represents the movement of Armenians during the Middle Ages, which is part of why I became interested in this culture early in my studies. I'm fascinated by how people and ideas move; what migrating communities choose to make, how they define themselves, and how they interact with other cultures.

Rachel High: Armenia was the first nation to convert officially to Christianity. Despite this, Armenia has been overlooked in the history of Christian art. Why? How does this book and exhibition hope to change that?

Helen Evans: Armenia is a country to the east of the East, right on the edge of Persia. In the nineteenth century, at the very beginning of the serious study of Christian art, it was not very accessible to the West, and I think that is why it has been excluded from the usual narrative. At the time, there was not a lot of Armenian art outside of Armenia. The Armenians were Christians before the rise of the Catholic Church, which further complicated things. Because of this, later generations perceived Armenians as people who were so isolated that they preserve the earliest of Christian traditions. That was not an accurate view, for the Armenians had amazing power on trade routes during the time period covered by the show and the book, and they interacted with all sorts of people passing through.

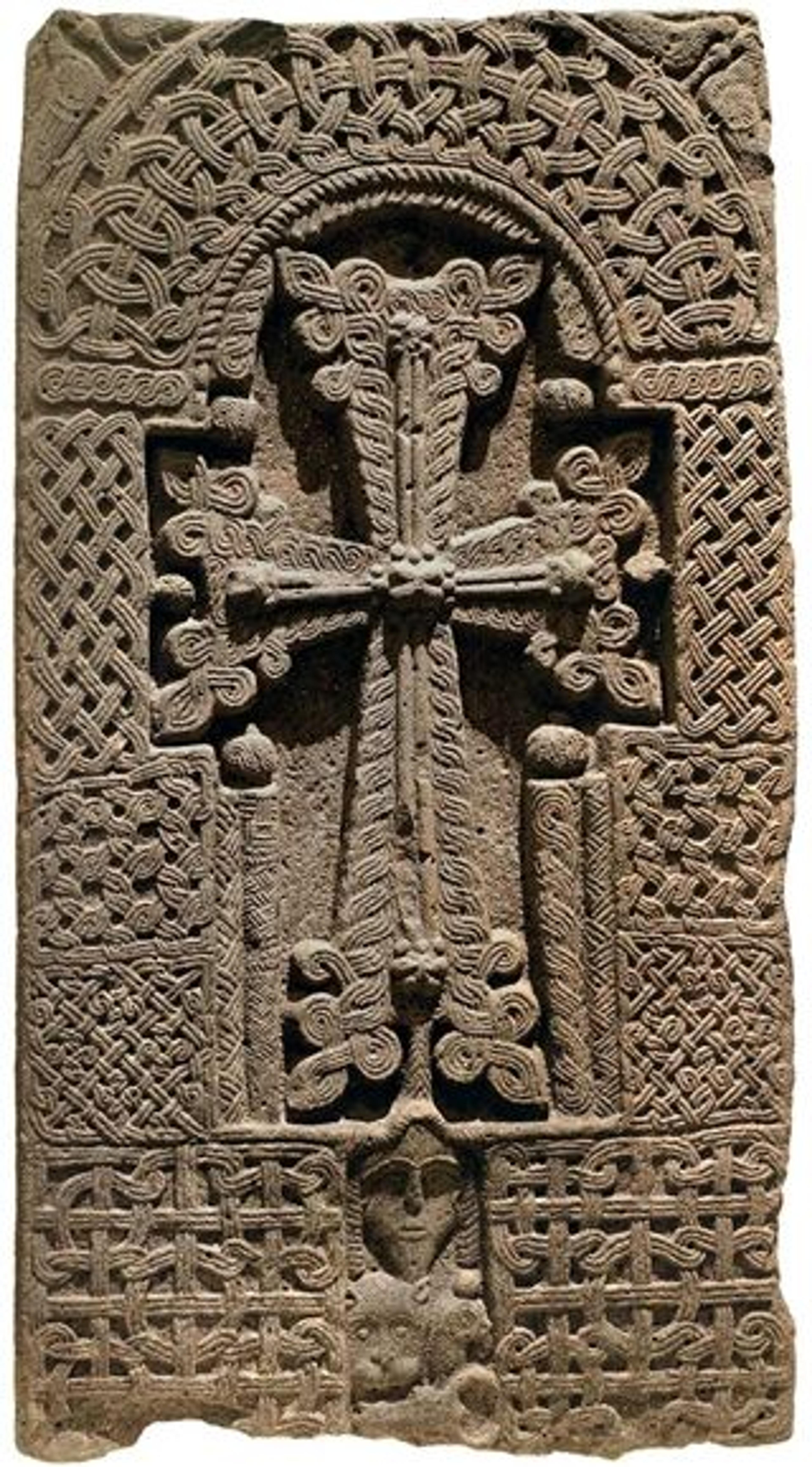

This khachkar, or carved Armenian stone cross, was the first to be displayed in a US museum and has been on view in The Met's medieval galleries since 2008. Khachkar, 12th–13th century. Lori Berd. Basalt, 72 x 38 3/4 x 9 in. (182.9 x 98.4 x 22.9 cm). History Museum of Armenia, Yerevan

In a conversation with Martin Gayford, published in the book Rendez-vous with Art, The Met's former director, Philippe de Montebello, spoke about the khachkar that we have had on loan since 2008 from the Republic of Armenia. He said, "In our effort to help conserve at least some of these impressive stone markers, we are in fact assigning a place for them in the history of Christian art."

We hope this exhibition and its catalogue will do just that—give Armenian art a chance to be part of the world's art.

Related Content

Armenia! is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through January 13, 2019.

Visit the places mentioned in this blog post on The Met's Interactive Map of Armenians in the Medieval World.

View the galleries in the exhibition's digital walkthrough.

Listen to the Audio Guide for the exhibition.

The exhibition catalogue is available at The Met Store.