Ruins of patriarchal palace of Dvin, 4th–7th century and later

Early church conferences held in Dvin's monumental religious complexes led to the Armenian declaration of separation from the broader Christian world. Dvin was also one of the richest cities east of Byzantium from the fifth to the seventh century; the jewelry hoard and ceramics found there are evidence that the city remained an important trading center until its destruction during invasions by the Seljuks, Mongols, and Timurids.

Walls of King Smbat II at Ani, 10th–13th century with modern restorations

As rival Armenian kingdoms developed, Armenian architecture flourished. From the tenth to the twelfth century, the Bagratid and Artsruni kings established churches in their capitals, like Ani, where extensive fortified walls indicate its importance on trade routes east and west. Handsome Armenian churches with pointed domes often had models of the churches placed on the gabled roofs or held by their donors in relief carvings on their exterior walls. In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the Orbelian, Proshian, and Zakarian families amassed great wealth from their central role on the trade routes controlled by the Mongols under the Pax Mongolica (Mongol peace) from China to the Mediterranean. These elite families funded the construction of religious buildings and donated sacred relics housed in elaborate containers, known as reliquaries, as gifts to churches and monasteries.

In the medieval period, cross stones, or khachkars, emerged as a special art form. Installed at significant historical sites and as grave markers, usually in areas under direct or indirect Muslim rule, khachkars are lasting evidence of the Armenians’ commitment to their Christian faith.

The fortifications of Sis

Armenians, forced to move west by the Byzantine Empire, established the kingdom of Cilicia on the Mediterranean coast under the Rupenid Armenian king Levon the Great in 1198/99. During the thirteenth century, the rival Cilician political family, the Hetumids, rose to power. From their capital at Sis, the Hetumid kings allied with the Crusader states and Louis IX of France, had close connections with the Catholic Church, and sought to supplant Byzantium as the dominant East Christian state.

Exceptional gilded manuscripts commissioned from Cilician scriptoria by members of the royal family and the elite clergy reflect the wealth and sophistication of the kingdom. Cilician artists combined traditional Armenian images with motifs borrowed from Western and Eastern cultures, indicating the kingdom’s close ties to European states and the Mongols. The famous artist T'oros Roslin—working at the scriptorium at Hromkla, the patriarchate, or headquarters, of the Armenian Church—created elegant images reflecting the cross-cultural ties of Cilicia that had a lasting impact on Armenian art.

Churches of the monastery of Sevan, Lake Sevan, 9th century and later

The monastery of Sevan, established in the ninth century, stands on a promontory, once an island, in Lake Sevan. Works related to the monastery complex are assembled here with images of its church of the Holy Apostles (Surb Arak‘elots‘). A variety of other liturgical works on view—including crosses in many materials and styles, censers, and church models—are the types of objects often donated by pious believers to such monasteries. Donors also gave elaborate silver and gilded containers to house relics, from those associated with the death of Christ, like the Holy Lance used at the Crucifixion, to ones famous for their connection to important Armenians, like the cross of Ashot II.

In the medieval period, numerous scriptoria were established to produce handsome manuscripts for Armenians at churches and monasteries in Greater Armenia as well as in Cilicia, Crimea, and Italy. One of the most important in Greater Armenia was at Gladzor, the site of a monastic school and an intellectual center famous at the time as a "second Athens." Some works produced in the Armenian homeland include motifs reflecting Islamic taste prevalent in the area. Others may have inspired Islamic manuscripts produced for Muslim Mongols. Armenian works created in Italy and Crimea show Western influence.

Monastery of Tat‘ev, Siwnik‘, 9th–13th century

As the Armenian Church especially honors the Gospels, the Word of God, manuscripts were particularly valued and venerated in the Middle Ages. Major scriptoria were established at monasteries with schools to create these texts and illuminations, with some of the most prominent at Gladzor and Tat‘ev.

Inscriptions (colophons) in Armenian manuscripts often identified the donor and the scribe who wrote the text, at times the illuminator and subsequent owners, and in some cases offered details of political and personal events. Through these inscriptions, schools of illuminators can be traced over generations. Armenian illuminators often depicted themselves and donors in their paintings, a rare occurrence in the Christian East. Some illuminations also provide evidence about the process of manuscript production, from polishing the paper to copying sources from model books. Whether the manuscripts were the work of highly trained artists or those driven by passion to portray events in the life of Christ and the Bible, all illuminations reflect the profound devotion of those participating in the making of the manuscript.

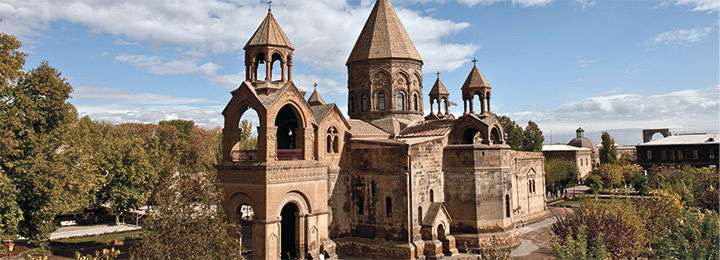

The Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, 4th century and later

Armenians were influential in two great empires during the last centuries of their medieval era. The Ottoman and Safavid Persian states emerged from the earlier invasions of the Near East by the Seljuks, Mongols, and Timurids. In the Ottoman Empire, Armenians flourished on important trade routes, especially ones associated with textiles. Major hubs of Armenian culture prospered in long-established religious centers in Jerusalem; in Sis, the former capital of the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia; and in Etchmiadzin, where the first Armenian Christian church is believed to have been built.

During this period, Armenians created majestic works of art in their religious centers and at sites, such as Kayseri, Kütayha, and Julfa, where they were dominant forces on trade routes. In Constantinople, where an Armenian patriarchate was established after it had been made capital of the Ottoman Empire in 1453, manuscripts were produced that revived the traditions of the kingdom of Cilicia and introduced new motifs from Western European printed books. A large map, made in Constantinople in 1691, shows in realistic detail all the Armenian churches in the empire, including those in Crimea. Drawn by an Armenian for a Western patron, it is evidence of Western interest in Armenians and the breadth of their presence in the Ottoman Empire.

Interior of the Holy Savior Cathedral, Isfahan, 1664

Armenians from the wealthy city of Julfa, where they had long dominated the silk trade, were required in 1604 to relocate to Isfahan, the new capital of the Safavid Perisan dynasty, at the demand of its ruler Shah ‘Abbas I. The move was devastating to many Armenians, but within a few years elite Armenian merchants (khojas) in Isfahan controlled all external trade of the powerful Safavid state from England to the Philippines and Russia to India. Their palaces and churches in New Julfa, their residential section in Isfahan, combined traditional Armenian motifs with Western and other sources drawn from their trade routes. These merchants also commissioned manuscripts that display a similar hybrid of traditional and foreign styles.

In 1666, the khojas of New Julfa, assisted by the Armenian elite of Constantinople, finally succeeded in funding the printing of a Bible in the Armenian language. Produced in Amsterdam, it would be followed by an elaborate world map in Armenian, printed there in 1695. Made for the merchant elite, this map reflects their wealth and awareness of their impressive world-wide contacts. Even as the Armenian medieval centuries concluded with more and more books printed in their language, the influence of this sophisticated era continued, and its vibrant expression of the unique Armenian identity remains alive today.

Altar frontal (detail). New Julfa, 1741. Gold, silver, and silk threads on silk, 26 5/8 x 38 3/8 in. (67.5 x 97.5 cm). Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin (626). Photo by Hrair Hawk Khatcherian