The Poet and Author of the Gita Govinda, Jayadeva, Visualizes Radha and Krishna, ca. 1775–80. Folio from the Tehri Garhwal series of the Gita Govinda. India, Punjab Hills, kingdom of Kangra or Guler. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, image (painting): 5 3/4 x 9 3/4 in. (14.6 x 24.8 cm). Promised Gift of Steven Kossak, The Kronos Collections, 2015

A small but remarkably innovative body of miniature paintings was produced in the eighteenth century by tiny regional courts in the foothills of the Himalayas. These workshops drew inspiration from canonical Hindu texts in an effort to make the divine manifest and accessible for their royal patrons. Several of these exquisite works are on view in Seeing the Divine: Pahari Painting of North India, through July 21, 2019.

In one lovely folio, the great poet Jayadeva, author of the devotional poem the Gita Govinda, stands before Krishna and Radha (above). Dressed in the pure white dress of a Pahari singer, he holds a stringed double-gourd instrument, a vina, which he played as he sang the verses of his devotional poem. The verses on the back of the painting tell us:

His musical skill, his meditation on Vishnu,

His vision of reality in the erotic mood,

His graceful play in these poems,

All show that the master-poet Jayadeva's soul is in perfect tune with Krishna.

The artist's representation suggests that by aligning himself in this way with Krishna, the poet is able to evoke the divine and look into the god's eyes, a key act of devotion in Hinduism. With one arm around Radha, Krishna holds a flute and stands in an open landscape, accessible to his devotee.

Raja Sidh Sen's Vision of Savari Durga, ca. 1720. Attributed to The Mandi Master (active first half of the 18th century). India, Punjab Hills, court of Mandi. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, Painting: 11 1/8 x 7 3/8 in. (28.3 cm x 18.7 cm). Promised Gift of Steven Kossak, The Kronos Collections

Across the Punjab hills, artists and patrons worked together to find new ways to evoke the gods. As in the image of Jayadeva, the patrons are often shown in the act of having visions and looking into the eyes of powerful Hindu gods. Raja Sidh Sen's Vision of Savari Durga (above) was done by an unusual artist known as the Mandi Master (active between 1690 and 1730). The intentional simplicity of the execution—its saturated colors achieved with roughly ground pigments laid down in thick layers—makes no attempt to present a realistic likeness of the artist's patron. Instead, it gives us a powerful and deeply personal portrait of a ruler, Sidh Sen, who we know claimed to have tantric powers.

Sidh Sen stands almost arrogantly before the goddess, who in turn confronts her devotee as a terrifying presence, gazing at him with bloodshot eyes and blowing a horn. In one of her four hands Durga holds a skull cup in the form of the freshly cut crown of a human head that still bears the three red tilak stripes worn by her followers. The crows flying above her—and the jackals at her feet—hint at charnel grounds.

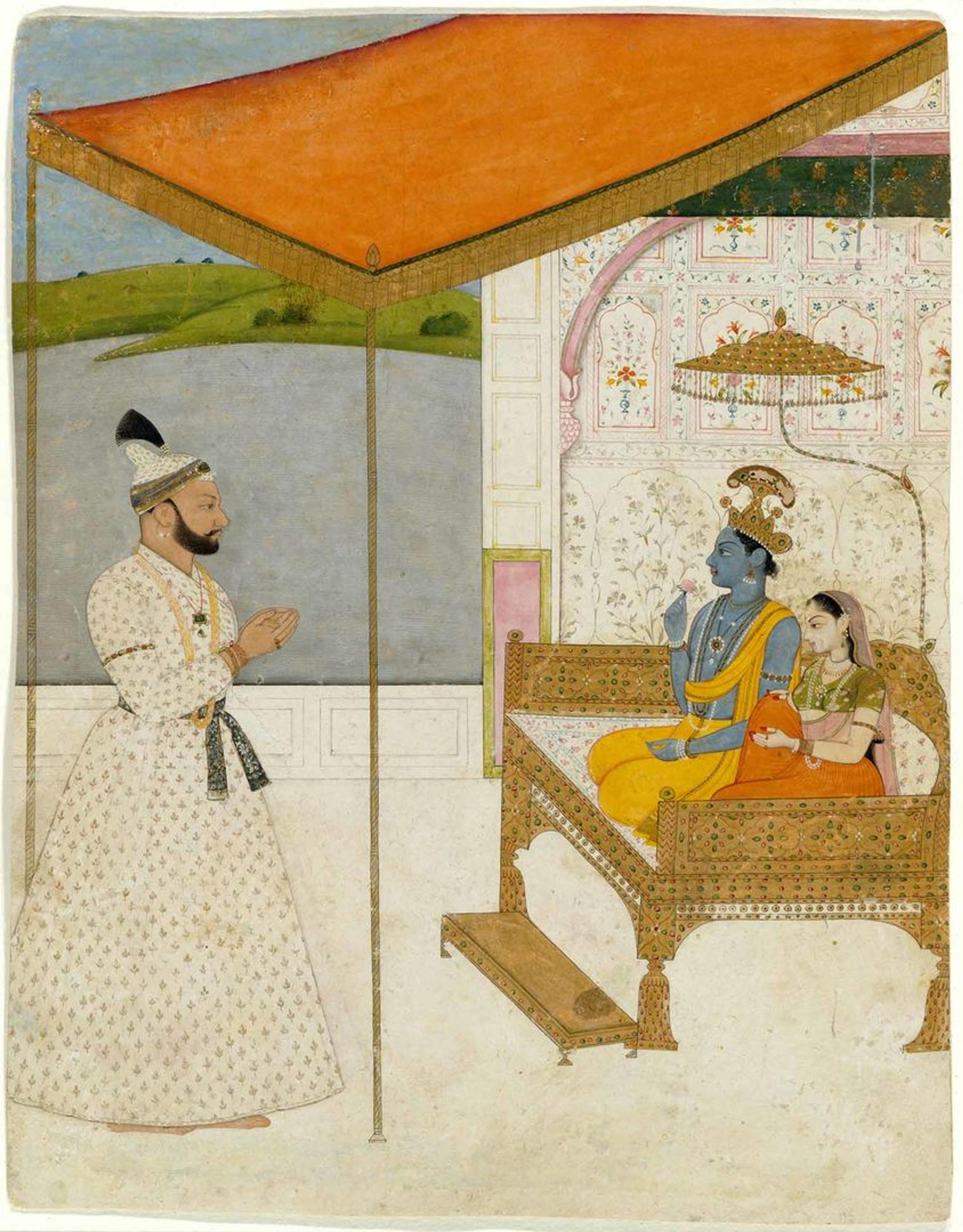

Raja Balwant Singh's Vision of Krishna and Radha, ca. 1745–50. Attributed to Nainsukh (active ca. 1735–78). India, Punjab Hills, kingdom of Jasrota. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, Overall: 7 3/4 x 6 1/8 in. (19.7 x 15.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1994 (1994.377)

In contrast to the bold, graphic work of the Mandi Master, the artist Nainsukh took a more refined and subtle approach to revealing the devotional vision of his patron, Balwant Sing (above). The painter relates the rolling hills of his patron's kingdom to a sacred realm—a decorated interior space, demarcated by an orange canopy and occupied by Krishna and Radha. The genius of Nainsukh's balanced composition lies in the way he provides lavish and opulent detail, while at the same time drawing attention to Krishna, who sits ever so peacefully holding a flower.

In seeking to give form to their devotional passion, these Pahari rulers, and the artists they sponsored, found new ways to relate to the gods. Out of this effort, dynastic portraiture that showed rulers at the same scale as the gods appears for the first time in the art of South Asia. In these geographically isolated courts in the Himalayan foothills, both artists and their patrons seem to have been unencumbered by long-standing iconographic conventions, leaving them free to evolve wide-ranging new modes for depicting the gods.

Seeing the Divine: Pahari Painting of North India is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through July 21, 2019.

Further Reading

Goswamy, B. N., and Eberhard Fischer. Pahari Masters: Court Painters of Northern India. Artibus Asiae Supplementum 38. Exh. cat. Zürich, Switzerland: Artibus Asiae Publishers: Museum Reitberg, 1992.

Guy, John, and Jorrit Britschgi. Wonder of the Age: Master Painters of India, 1100–1900. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: distributed by Yale University Press, 2011.

McInerney, Terence, Steven Kossak, and Navina Najat Haidar. Divine Pleasures: Painting from India's Rajput Courts. Exh. cat. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: distributed by Yale University Press, 2016.