Goya's Graphic Imagination features 166 illustrations and is available at The Met Store and on MetPublications. The publication is made possible by the Diane W. and James E. Burke Fund. Additional support provided by Fundación María Cristina Masaveu Peterson and Tavolozza Foundation.

The Met houses one of the best collections of Francisco de Goya y Lucientes's (1746–1828) prints and drawings outside Spain. Goya's Graphic Imagination—accompanying an exhibition at The Met on view through May 2, 2021—presents the first focused investigation of this work. Spanning six decades, Goya's graphic practice reflects the transformation and turmoil of the Enlightenment, the Inquisition, and Spain's years of constitutional government. The more than 100 featured works include his early etchings after Velázquez, print series such as Los Caprichos and The Disasters of War, late lithographs titled The Bulls of Bordeaux, and albums of drawings inspired by the artist's thoughts, dreams, and reactions to the world around him.

I spoke with Mark McDonald about this essential aspect of Goya's career and the ways in which his drawing and prints reveal much more about the artist than his celebrated paintings.

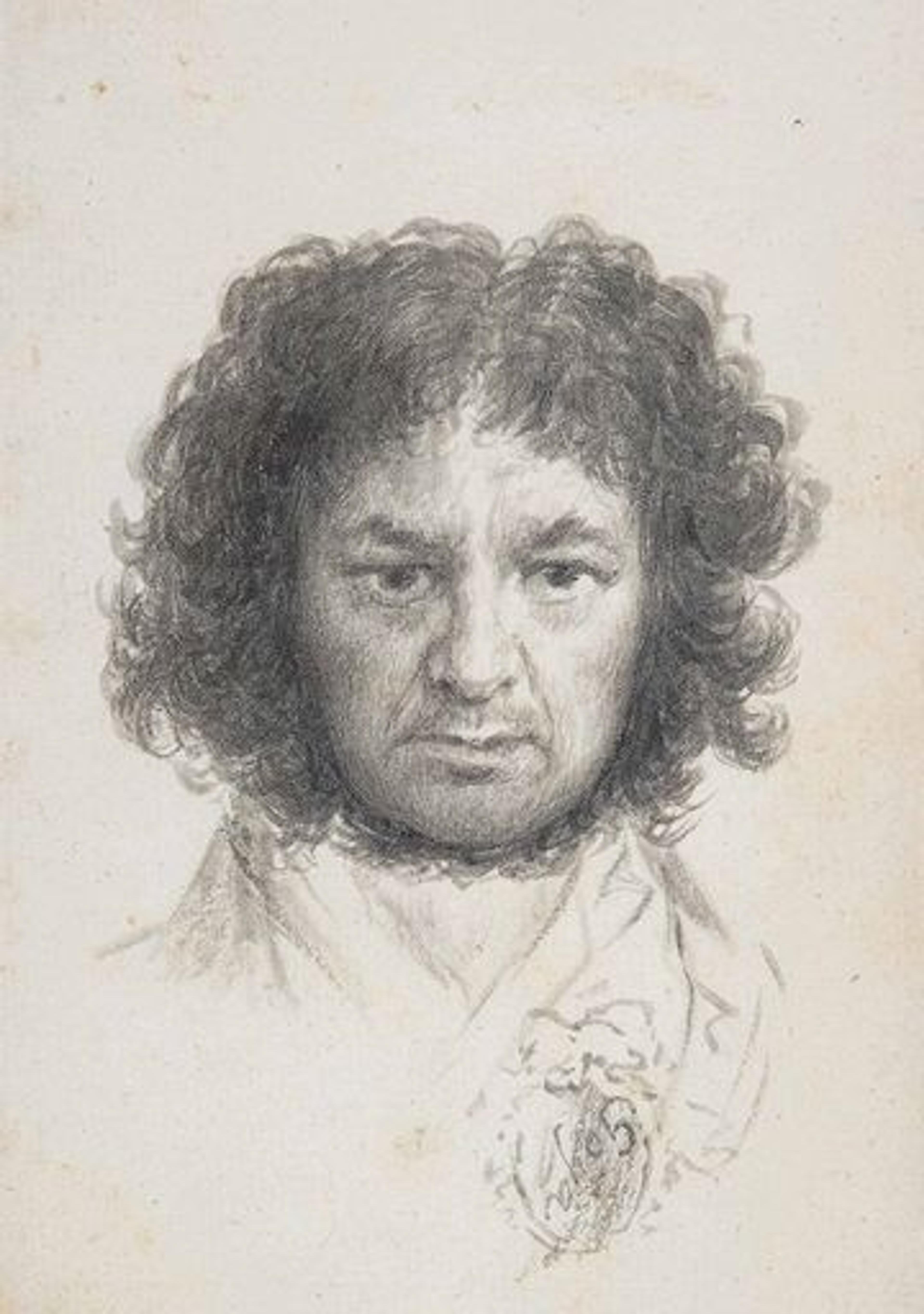

Goya (Francisco de Goya y Lucientes) (Spanish, Fuendetodos 1746–1828 Bordeaux). Self Portrait. Ca. 1796. Brush and point of brush, carbon black ink, on laid paper. 6 × 3 5/8 in. (15.3. × 9.1 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1935 (35.103.1).

Rachel High: Goya is such a well-loved artist, and readers might be surprised tolearn that this is the first book to address his full graphic practice in depth. Why is it important to consider Goya's prints and drawings together?

Mark McDonald: It is crucial because they are so intertwined. Both types of works on paper are closer to one another than they are to Goya's painting. Paintings are a public expression. By contrast, an album of drawings is intimate and personal. These smaller-scale works served as a platform for Goya to think through his most private ideas.

While it is far easier to speak about works in clear categories, I found that there is so much overlap and that it is impossible to extricate Goya's prints from his drawings. His themes intersect and interweave. Goya thought on paper through his prints and drawings.

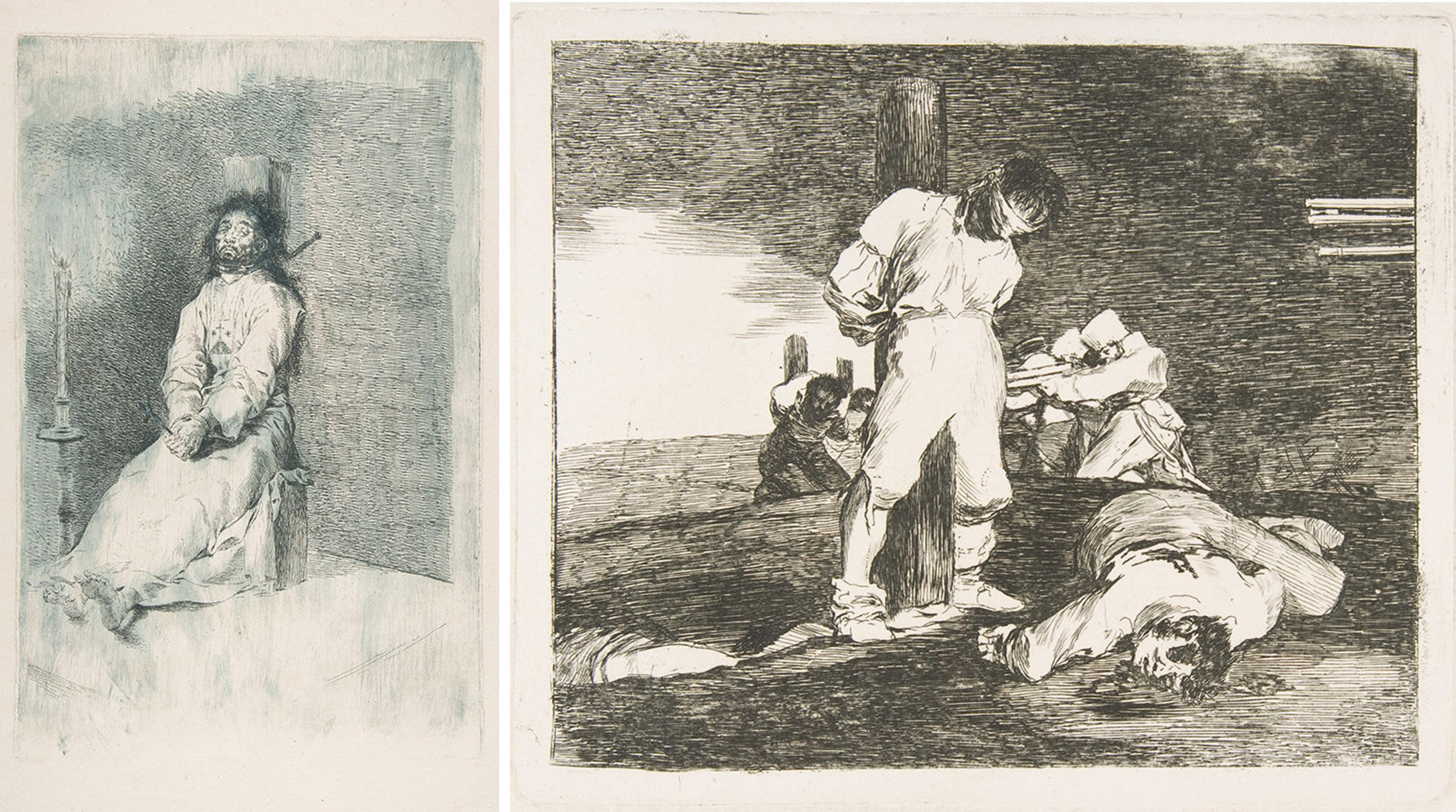

Goya revisited themes of death, violence, and human folly throughout his career.

Left: Goya (Francisco de Goya y Lucientes) (Spanish, Fuendetodos 1746–1828 Bordeaux). Garroted Man. Ca. 1775–78. Etching, printed in blue. Sheet: 16 15/16 × 12 1/4 in. (43 × 31 cm); plate: 12 7/8 × 8 1/4 in. (32.7 × 21 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1920 (20.22).

Right: Goya (Francisco de Goya y Lucientes) (Spanish, Fuendetodos 1746–1828 Bordeaux). Plate 15 from The Disasters of War (Los Desastres de la Guerra): 'And there is no help.' (Y no hai remedio.). 1810. Etching, drypoint, burin, burnisher. Sheet: 8 7/8 × 12 1/2 in. (22.5 × 31.8 cm); plate: 5 1/2 × 6 1/2 in. (14.1 × 16.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1932 (32.62.17).

Rachel High: As you just mentioned and as you discuss in your essay in the catalogue, Goya revisited many themes and techniques in his prints and drawings throughout his long career. Could you speak more about those reoccurring interests?

Mark McDonald: Fundamentally, Goya was focused on humanity—the things that motivate us—our actions, superstitions, ignorance, and fear. His work centers on the ways in which we manifest this publicly and privately—in our anxieties or our violence to ourselves and others. Goya did not create prints or drawings on history subjects, ornament, trees, or architecture. There are no seascapes, ships, or furniture. It all centers on us, our human essence. This is a theme that weaves through all of Goya's work. He is interested in what makes us human—in all its strangeness.

On the surface, this image depicts a horse attacked by a pack of foxes. As McDonald suggests in his book, this work has a deeper meaning and may reference the struggles between constitutional monarchy and reactionary forces.

Goya (Francisco de Goya y Lucientes) (Spanish, Fuendetodos 1746–1828 Bordeaux). Plate 78 from The Disasters of War (Los Desastres de la Guerra): 'He defends himself well.' (Se defiende bien.). After 1814–15 (published 1863). Etching, drypoint, burin, burnisher. Sheet: 9 7/8 × 13 5/8 in. (25 × 34.5 cm); plate: 7 × 8 5/8 in. (17.9 × 21.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Jacob H. Schiff Bequest, 1922 (22.60.25[78]).

Rachel High: As you address in the book's robust catalogue section, Goya is always speaking to a larger human significance, even when the subjects depicted might be animals, mythical creatures, or landscapes.

Mark McDonald: There's often no singular subject. Today we are obsessed with understanding narrative boundaries, but Goya’s prints and drawings allow meaning to emerge in the absence of subject; this is part of what gives these works their eternal appeal.

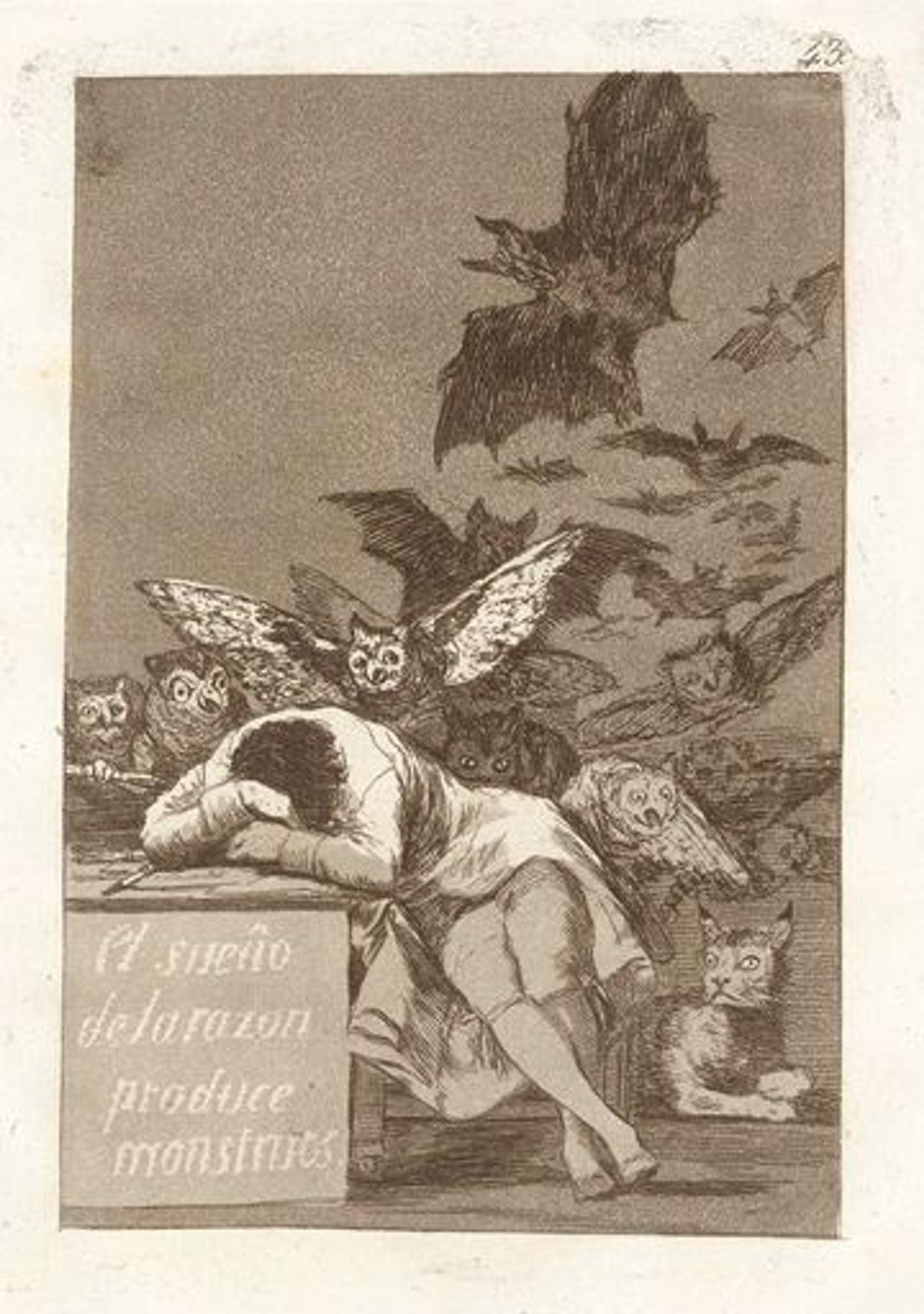

Goya (Francisco de Goya y Lucientes) (Spanish, Fuendetodos 1746–1828 Bordeaux). Plate 43 from Los Caprichos: 'The sleep of reason produces monsters.' (El sueño de la razon produce monstruos.). 1799. Etching, aquatint. Sheet: 11 5/8 × 8 1/4 in. (29.5 × 21 cm); plate: 8 5/16 × 6 in. (21.4 × 15.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of M. Knoedler & Co., 1918 (18.64[43]).

Rachel High: Your object-focused approach to Goya's work reminds me of The Met's How to Read series. The series gives readers tools for looking at and understanding areas of art history through specific case studies. In some ways, this catalogue is like a more comprehensive How to Read book of Goya's drawings and prints; the entries teach you how to approach his work. Goya's inscriptions are particularly fascinating in this regard. What insight can readers glean from them?

Mark McDonald: I've approximated meaning for many of the inscriptions, but I'm not telling the reader "This means this," or "That means that." I'm giving them multiple ways of understanding a work: "This might address A, B, or C."

It is important to emphasize that the inscriptions are not titles. They are captions that encourage a potential understanding. The captions do not explain the work for us. The meanings are often unclear, but this isn't because Goya was being obtuse. He was thinking through drawings and prints for his personal purposes, and as such, there is no need for him to explain their significance to himself. His works on paper are so internal and layered that they would have sparked multiple associations, even for Goya.

The meanings are also intended to change and evolve over time. Goya's works do not provide a finite set of understandings. So much of the meaning is dependent on Goya's thoughts, dreams, and visions. It is no surprise that through such mobile imagery, meaning also changes.

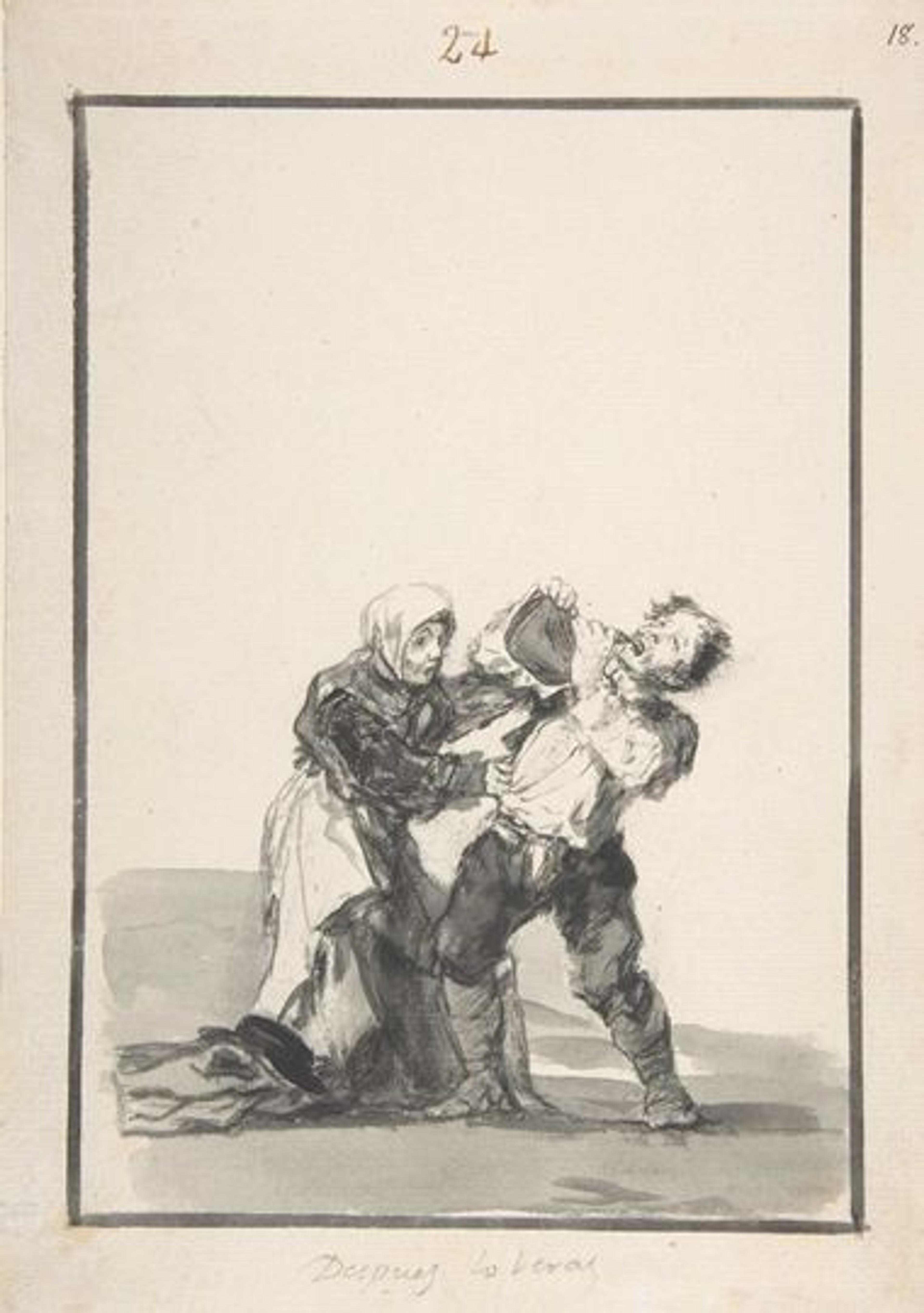

Goya (Francisco de Goya y Lucientes) (Spanish, Fuendetodos 1746–1828 Bordeaux). Album E, page 24, 'You'll see later.' (Despues lo veras). 1816. Brush, carbon black and grey ink and wash, scraper, on laid paper. 10 1/2 × 7 3/8 in. (26.8 × 18.9 cm); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1935 (35.103.18).

We often fixate on strict narrative categories—start, middle, end; A, B, C; first page, final page. Goya was more intuitive than that. He captured moments from the environment around him that explode to a stage of importance in his work. Prints and drawings express an image's transitory nature but also its immediacy and significance. Through small details, so much is conveyed; glances or gestures take on universal meaning as micro-symbols alluding to more important concerns. Goya created frozen moments in time that capture our thought and actions.

Goya's work is like a figure eight—there's no start, and there's no end. Sometimes meanings will converge in the center, but they will ultimately turn, move, and part ways. Meaning floats in a non-finite, non-sequential interactive pattern as we might experience fragments of a dream.

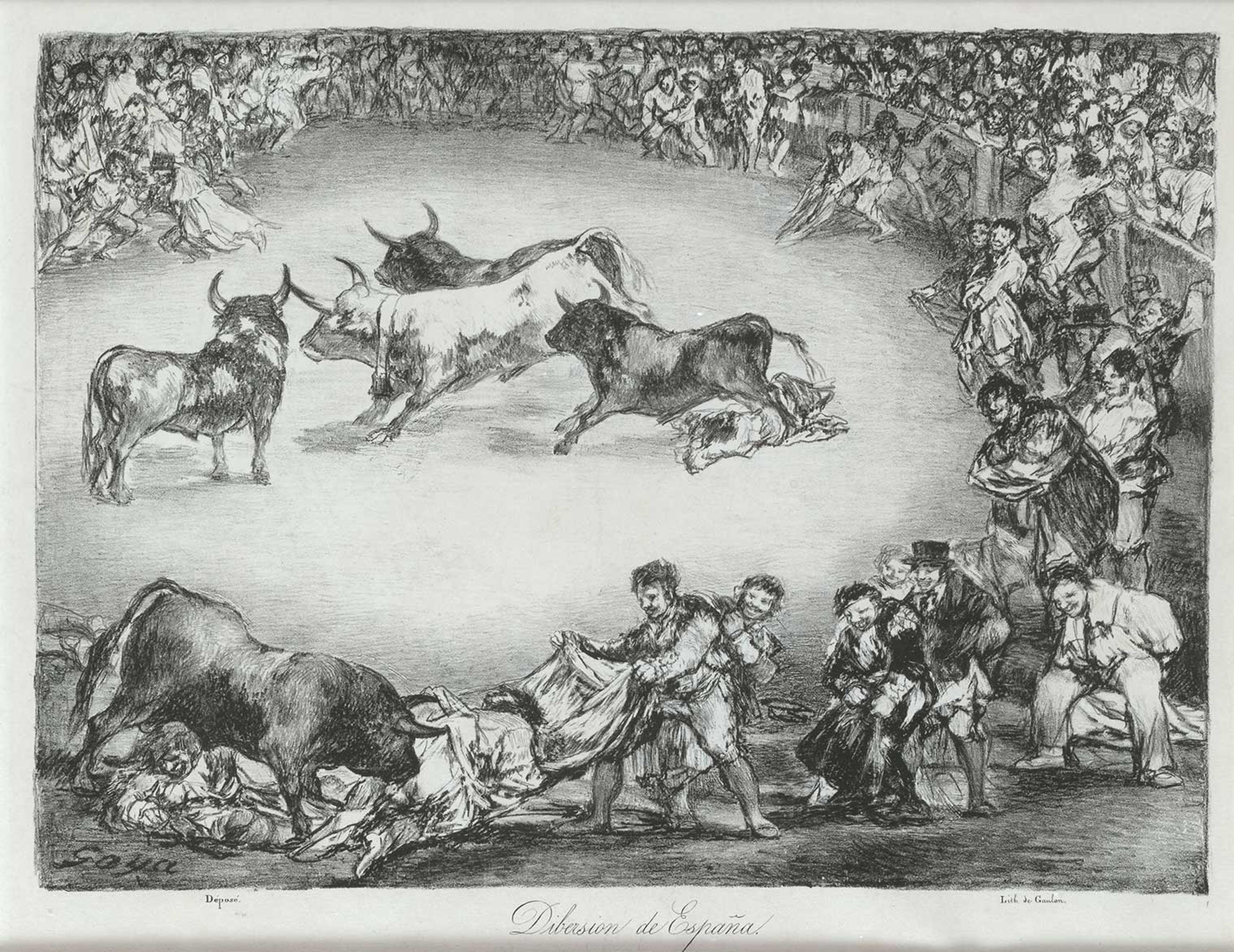

Goya (Francisco de Goya y Lucientes) (Spanish, Fuendetodos 1746–1828 Bordeaux). Bulls of Bordeaux: 'Spanish Entertainment.' 1825. Lithograph. Sheet: 16 5/8 × 20 7/8 in. (42.2 × 53 cm); plate: 12 × 16 3/8 in. (30.4 × 41.5 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1920 (20.63.2).

Rachel High: I love that analogy. It is interesting to think about that when comparing Goya's times to our own. He worked during an especially tumultuous point in Spain's history. Today, many of us feel as though we're living through a chaotic moment too. What do you hope that readers might take away from Goya's work in this context?

Mark McDonald: Not much changes. The same idiocy, cruelty, and violence take new shapes, but Goya captured those universal anxieties. So much of what we are dealing with now can be identified in Goya's art—there's politics, conflict, bloodshed, and ignorance of the impact of our actions fueled by stupidity and bad choices—the same old problems.

Rachel High: It's the figure eight.

Mark McDonald: Exactly. Goya showed these failings in such insightful imagery. The impact of his work merges from then into now.