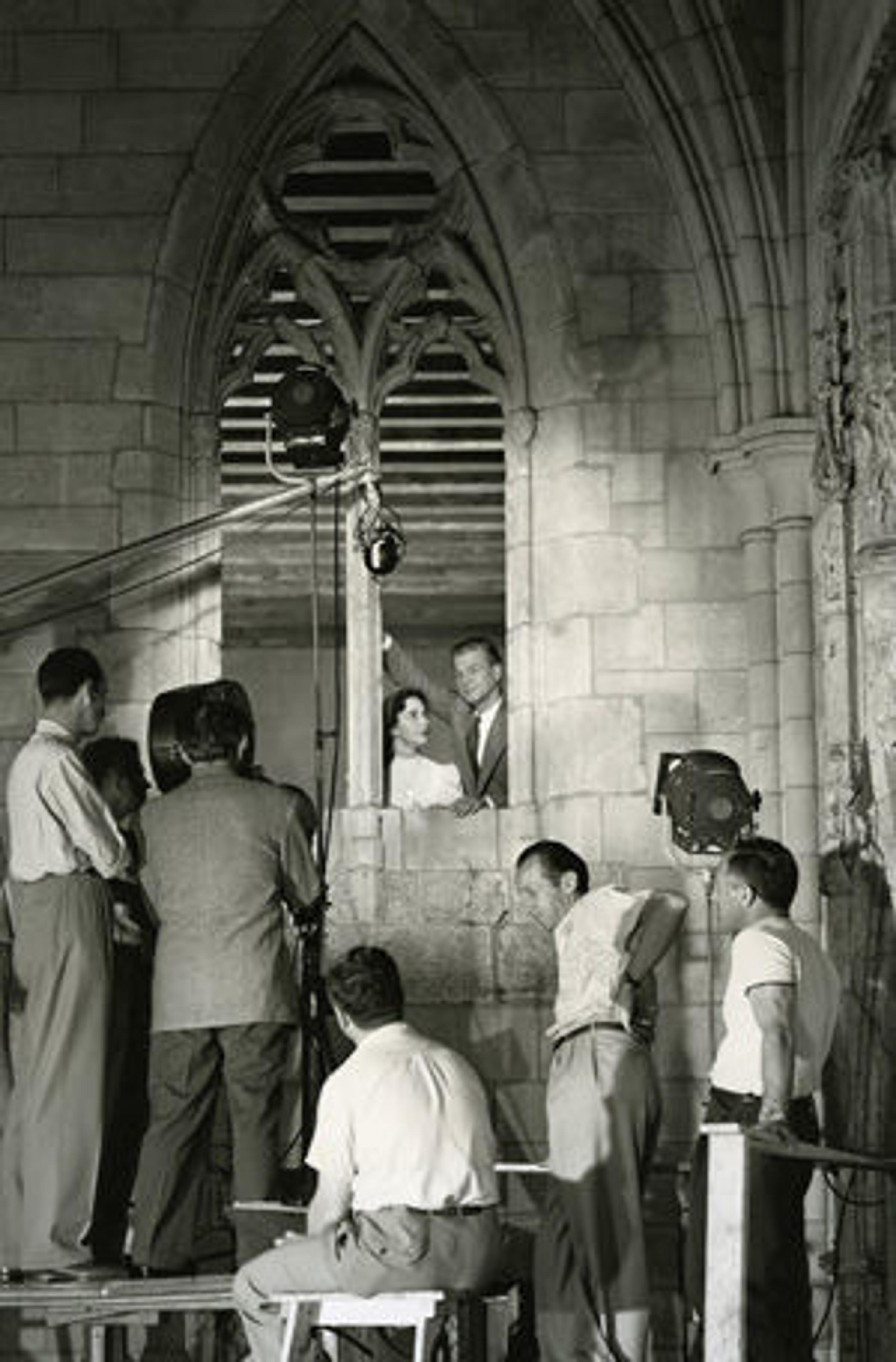

Joseph Cotton and Lillian Gish pose in the Cloister from Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa (25.120.398–.954) during the filming of Portrait of Jennie in 1947.

«For the past seventy-five years, The Cloisters has provided visitors with more than just a chance to view an exceptional collection of medieval art and architecture. In tourist guides and travel reviews, a trip to The Cloisters is commonly described as a way to be transported to the Middle Ages or—for locals seeking a "staycation"—a chance to get out of New York without leaving the city. The powerful effect of the place has clearly been noticed by screenwriters, novelists, and even comicbook authors, who have set a fair number of fictional works here over the years.»

The Cloisters offers a setting that is at once inside and out of the city, of the Old World and the New. The interplay between the medieval and the modern in how it's been presented predates the 1938 opening of the Museum we know today. (Read about the history of The Cloisters.) In 1925, as part of a series of dramatic films created to highlight different curatorial departments, the Met produced The Hidden Talisman, a silent short featuring the lively story of the ghost of a fifteenth-century French lady transported to the original Cloisters to scour the building's medieval architectural elements for a token left by her lost lover.

The Hidden Talisman: A Ghostly Romance of the Cloisters, filmed at the original Cloisters, 1928

In films shot at the "new" Cloisters (after 1938), some directors have made use of the location as a substitute for an atmospheric historic structure, unrelated to its identity as an art museum. In 1948, the experimental filmmaker Maya Deren used the ramparts of The Cloisters and their dramatic view of New Jersey's Palisades to create a timeless backdrop for her short film Meditation on Violence. William Dieterle's film of the same year, Portrait of Jennie, includes extended scenes featuring The Cloisters as an abbey housing Jennifer Jones, the object of Joseph Cotten's obsession.

Joseph Cotten and Jennifer Jones peer through the double-lancet window from La Tricherie, France (34.20.1) during filming for Portrait of Jennie.

Hal Hartley's 1994 film Amateur also casts the Museum as an ecclesiastical site, home to Isabelle Huppert's adult fiction–writing nun. Al Pacino, as Shakespeare's Richard III, set the Museum as the locus of the king's conspiracies in 1996's Looking for Richard. Watching these films now reveals how little the atmosphere at The Cloisters has changed over the years: the view from the ramparts is largely unaltered since Deren's time, and chirping sparrows in Cuxa Cloister can still be heard today, just as they are in a scene from Portrait of Jennie.

When The Cloisters stars as itself—not just a generic historic structure—it tends to appear as a place of respite from the busy tempo of the city and, often, rising plot tension. In The Front (directed by Martin Ritt, 1976), The Devil's Own (Alan J. Pakula, 1997), and Keeping the Faith (Edward Norton, 2000), lead characters visit the gardens of The Cloisters in search of relief from growing tribulations. In all three instances, the gardens provide an important bit of breathing space before the characters and plot return to the anxieties of more urban settings.

Clint Eastwood and Susan Clark take in the view of The Cloisters from the Linden Terrace of Fort Tryon Park in the 1968 film Coogan's Bluff.

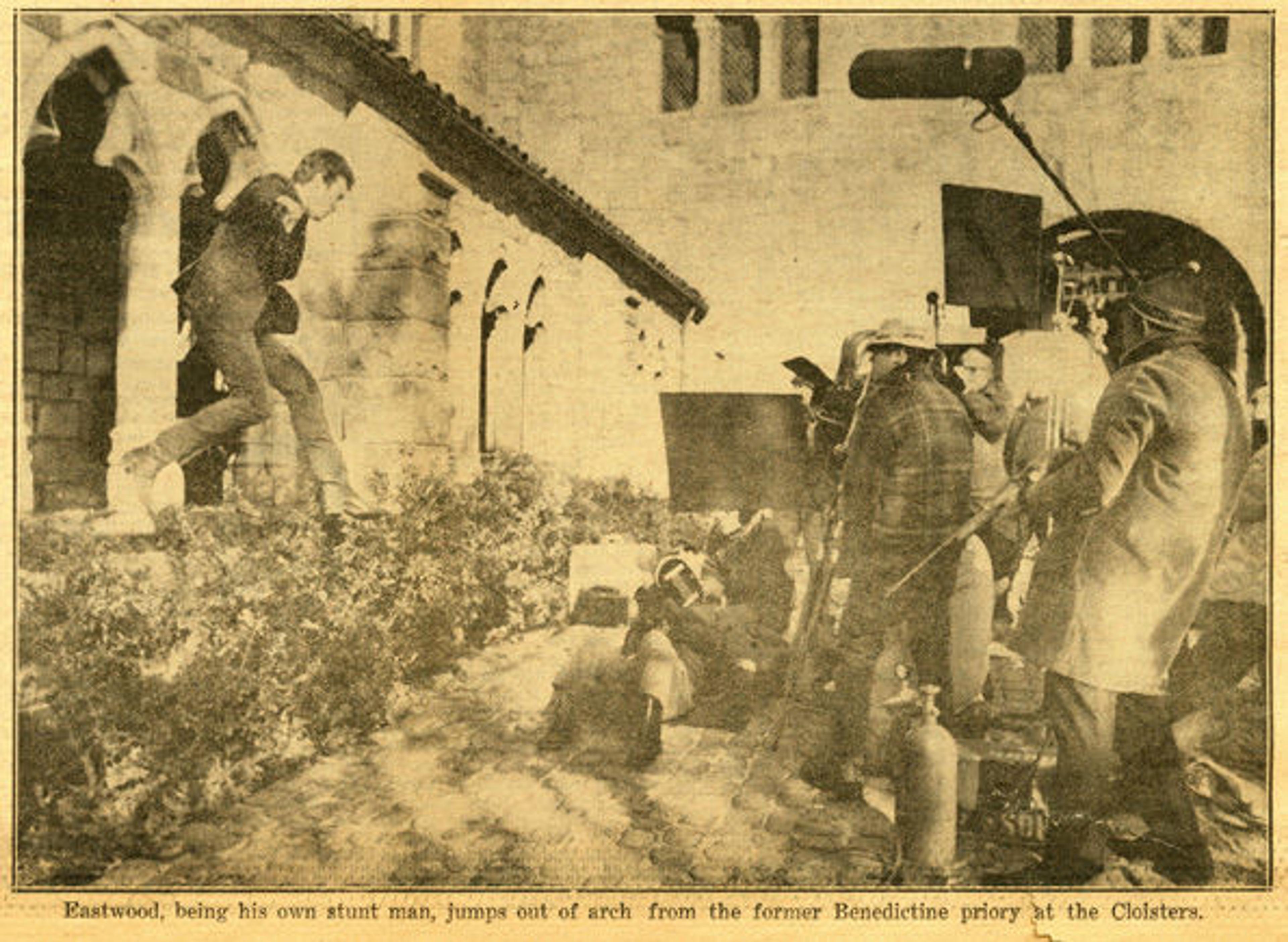

Some fictional characters don't appreciate the relaxing lure of The Cloisters. When Clint Eastwood, playing an embittered Arizona sheriff who has traveled to New York on the trail of an escaped killer, grows frustrated with the city's legal system in the 1968 film Coogan's Bluff (directed by Don Siegel), a kind-hearted probation officer played by Susan Clark tries to help him relax by taking him on a visit to The Cloisters. Apparently uninterested, he opts for a spaghetti dinner at her place instead. At the film's end, however, Coogan returns to the Museum, where the fugitive has (inexplicably) managed to find a safe hideout. The movie's climax consists of a prolonged motorcycle chase through the Heather Garden in Fort Tryon Park.

Clint Eastwood leaps from one of the windows of the Froville arcade (35.35.5–12) during filming of Coogan's Bluff at The Cloisters. NY Daily News, Nov. 21, 1967

The Cloisters also provides a nice spot for romantic interludes: a turning point in 2009's The Good Guy, directed by Julio Depietro, occurs when the young couple shares a clandestine candlelit evening in the herb garden of Bonnefont Cloister.

Unlike its role on film (or in real life), the Museum's depiction in popular literature is not always idyllic. Apart from Herman Wouk's 1955 novel Marjorie Morningstar, in which a visit to The Cloisters and a kiss in the Heather Garden proves to be a resonant memory throughout the book, many works—particularly those in the thriller and suspense genres—offer up something quite different.

For example, Linda Fairstein's The Bone Vault (New York: Scribner, 2003), which centers around the discovery of the body of a Cloisters research assistant inside an Egyptian sarcophagus, features an abundance of intrigue. In Mary Jane Clark's When Day Breaks (New York: Morrow, 2007), the theft of a loaned unicorn amulet plays a central role in a murder investigation, culminating in a confrontation between competing television news show hosts and a fatal plunge off the high hills outside the ramparts. The temptation to mystify the ambience of The Cloisters is not lost on authors seeking to infuse a New York story with something of the (literary) Gothic.

In some cases, the religious origins of the medieval architectural elements are key. The protagonist of Han Nolan's When We Were Saints (Orlando: Harcourt, 2003) meets a boy from the South whom she is convinced shares her spiritual powers, and she takes him to live in The Cloisters. And in James Morrow's Towing Jehovah (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1994), the main character meets the archangel Raphael after completing a ritual midnight bath in the Cuxa Cloister fountain.

Comic book authors have also taken advantage of the perceived remoteness and mystery of The Cloisters as a backdrop for action that falls just outside the urban realm of their characters. In 1980, Spider-Man confronted a vengeful crusader named the Rapier in a duel that took them through the galleries and gardens (The Spectacular Spider-Man Annual Vol. 1, no.2, New York: Marvel Comics Group, 1980). More recently, 2008's Nightwing series featured Batman's Robin, in a new guise, encamped at The Cloisters (New York: DC Comics, 2008). After happening across the theft of a skeleton from the Tomb Effigy of Jean d'Alluye (25.120.201)—which, in reality, is empty—he lands the job of curator, closes the Museum for several months under the pretense of renovations, sends the entire staff home, and uses the tower offices as his base of operations. (Camping out at The Cloisters is a recurring feature in fictional depictions, and the fantasy of undetected after-hours access is popular among fans of many other museums as well!)

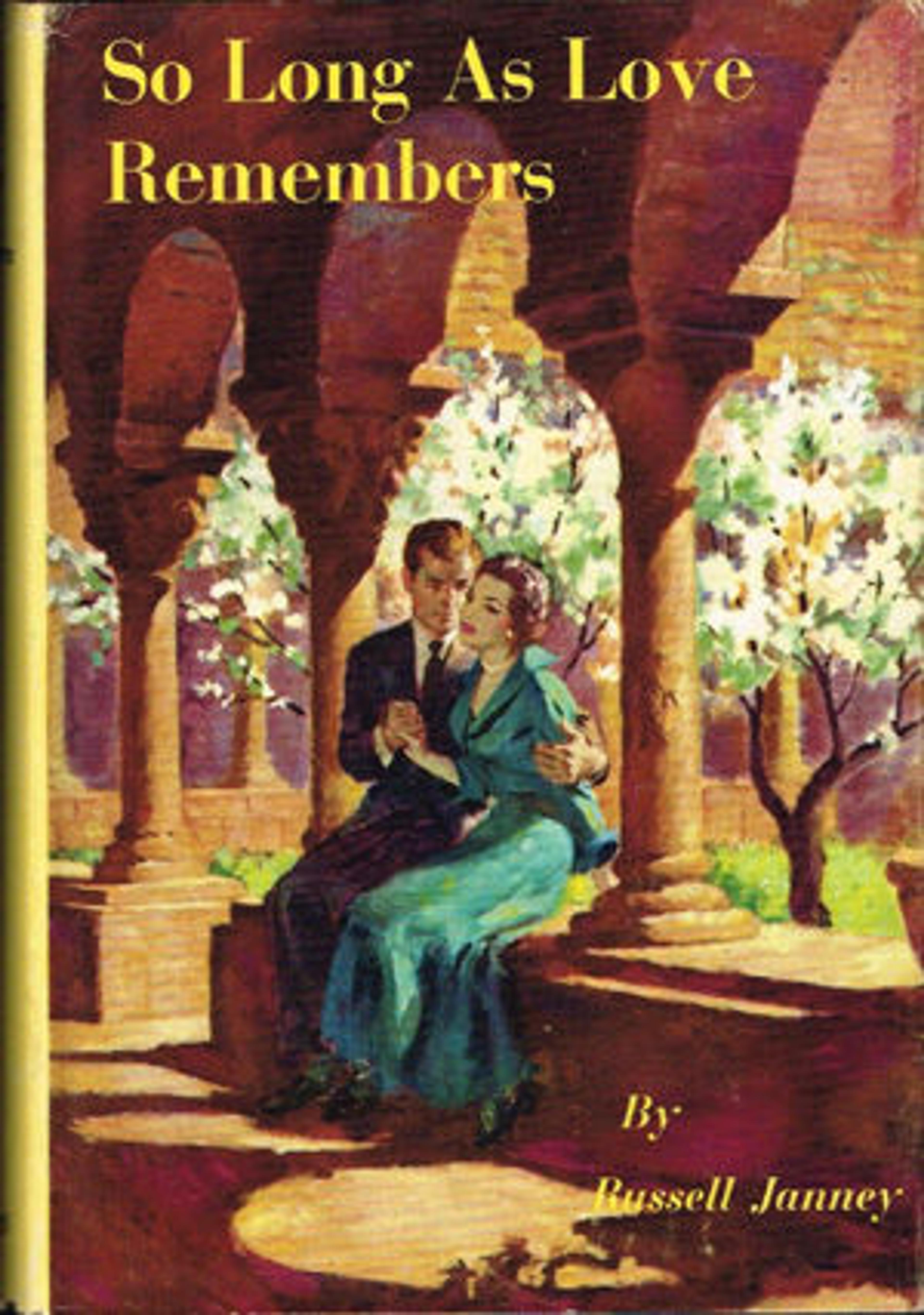

In some novels, specific works from the collection drive the plot. In Russell Janney's So Long as Love Remembers (New York: Hermitage House, 1953), a twelfth-century sandstone virgin sculpture is the object of a multigenerational curse that ends in the death of a Ziegfeld chorus girl from Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. The statue, which we discover was modeled on a direct ancestor of the girl, responds to the turning points in the story with smiles, laughter, and bleeding.

Jacket illustration for So Long as Love Remembers by Russell Janney (New York: Hermitage House, 1953) featuring the Cloister from Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa (25.120.398–.954), though here apparently constructed of brick instead of pink marble

The key turning point in Lee Carroll's paranormal mystery Black Swan Rising (New York: Tor, 2010) occurs after a mysterious fog rolls through The Cloisters, causing the small figure of a manticore in the Narbonne arch doorway (22.58.1a) to spring to life and attack the book's narrator. (The first victim is The Cloisters librarian, who dies of heart failure when he sees the little beast.) Another featured object is the birchwood statue of the Enthroned Virgin and Child from Autun, France (47.101.15), which causes a dispute between the main characters in When We Were Saints but creates a lasting bond between the narrator and her dead friend in Carol Rifka Brunt's Tell the Wolves I'm Home (New York: Dial Press, 2012).

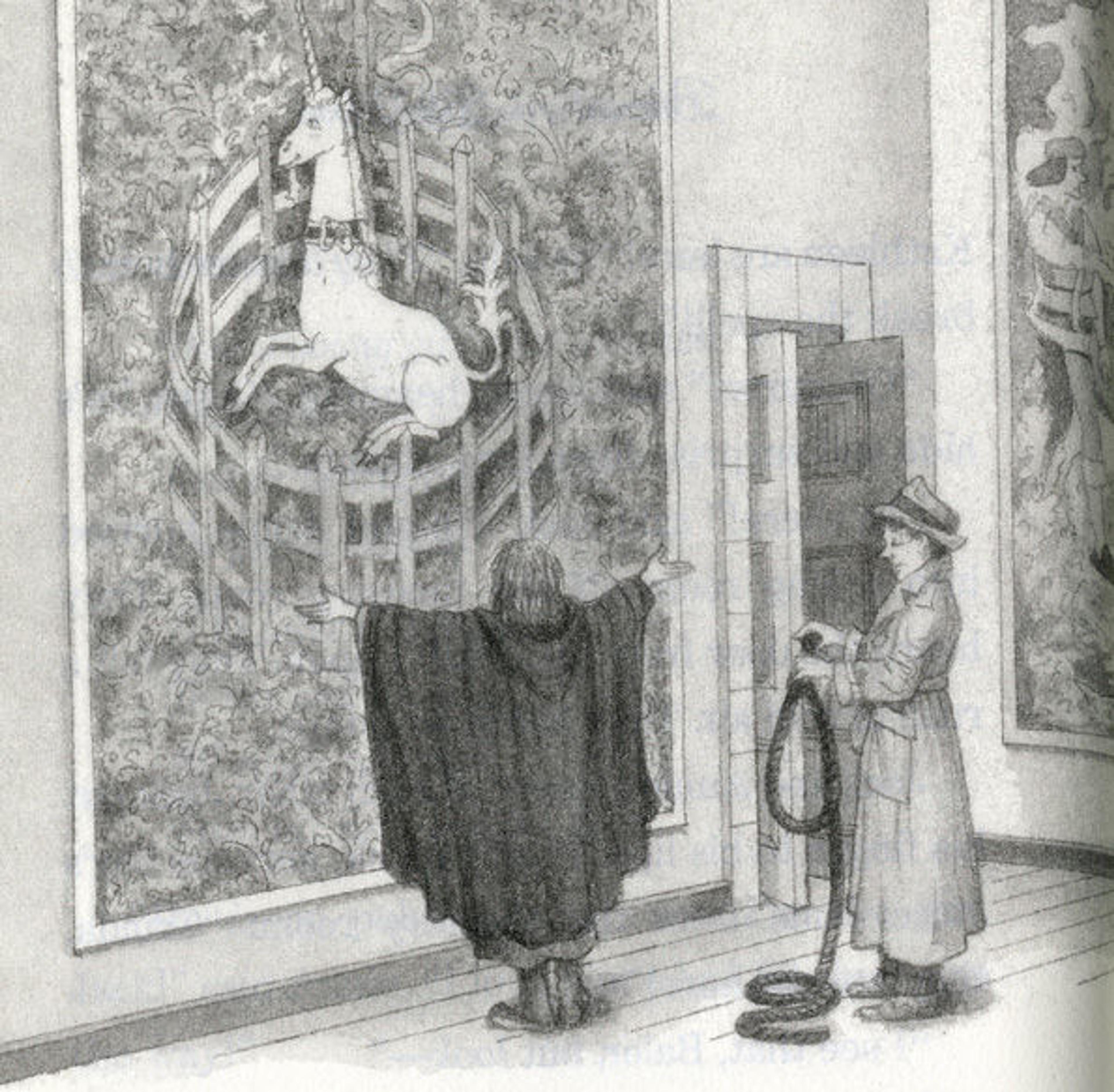

Of course, the treasured Unicorn Tapestries have lured several writers as well. Anne Morrow Lindbergh composed a series of poems inspired by the pieces (The Unicorn and Other Poems 1935–1955. New York: Pantheon, 1956), and the troubled main character in James Lasdun's The Horned Man (New York; London: W.W. Norton, 2002) confronts the meaning of the growth developing on his head with a visit to the tapestries. In the children's book Blizzard of the Blue Moon (New York: Random House, 2006), the protagonists are transported back to 1938, the year of The Cloisters' opening, to free the unicorn from his captivity in the tapestries.

The characters Grinda and Balor attempt to awaken the Unicorn in Captivity (37.80.6) in Blizzard of the Blue Moon (New York: Random House, 2006).

Alice Elayne, the heroine in C.C. Humphreys's young-adult work The Hunt of the Unicorn (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011), is literally pulled into the Unicorn in Captivity tapestry (37.80.6) during a school field trip. She spends the rest of the story with a unicorn named Moonspill in the fantasy world of Goloth (where she, too, is attacked by a manticore) until being returned with a thud to the hardwood floor of the gallery.

Perhaps the recurring treatment of The Cloisters as a portal to another realm is understandable given the dichotomy of medieval architecture that is accessible by subway: it is a location that feels far older and more remote than it actually is. This sense of timelessness resonated with the Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges, who may have said it best in his poem titled simply, "The Cloisters":

From a place in the kingdom of France

They brought the stained glass and the stones

to build on the island of Manhattanthese hollow Cloisters.

They are not apocryphal.

They are faithful monuments to a nostalgia.

An American voice tells us

to pay for what we want,

because this whole building is an invention

and the money as it leaves our hand

will become shekels or vanish like smoke.

This abbey strikes more terror

than the pyramid of Giza

or the labyrinth at Knossos,

because it too is a dream.

We hear the fountain's murmur,

but that fountain's in the Patio of the Orange Trees

or the epic of Der Asra.

We hear clear Latin voices

but those voices echoed in Aquitaine

when it was a stone's throw from Islam.

We see in the tapestries

the resurrection and the death

of the white condemned unicorn,

because time in this place

does not obey an order.

The laurel trees I touch will flower

when Leif Ericsson sights the sands of America.

I feel a touch of vertigo.

I am not used to eternity.

"The Cloisters" (excerpt), by Jorge Luis Borges, from La Cifra (1981)

Translated from the Spanish by Suzanne Jill Levine