«As of 1888, when Mary Elizabeth Brown was preparing her first catalog of the 270 instruments that would soon be gifted to the Metropolitan Museum, she had acquired approximately three dozen American instruments (some of which were collected through her family's network of missionaries). These examples came primarily from Sioux, Apache, and Pueblo peoples, with a few from Cuba, Mexico, Alaska, and Canada (which Brown referred to as "British America"). It appears to have been relatives in St. Paul, Minnesota, that put her in touch with agents and traders west of the Mississippi.» By far the most colorful character must have been Robert Ormsby Sweeny—an artist, druggist, and pharmacist in St. Paul who additionally described himself as:

Proprietor and Manafacturer [sic] of Sweeny's Wild Cherry Cough Syrup, Cholera Mixture. Stewart's Cough Syrup. Corn and Wart Cure. Dysmenorrhoea Drops. Neuralgiafuge. Toothache Drops. Indelible Ink. Pink of Pink Tooth Powder.

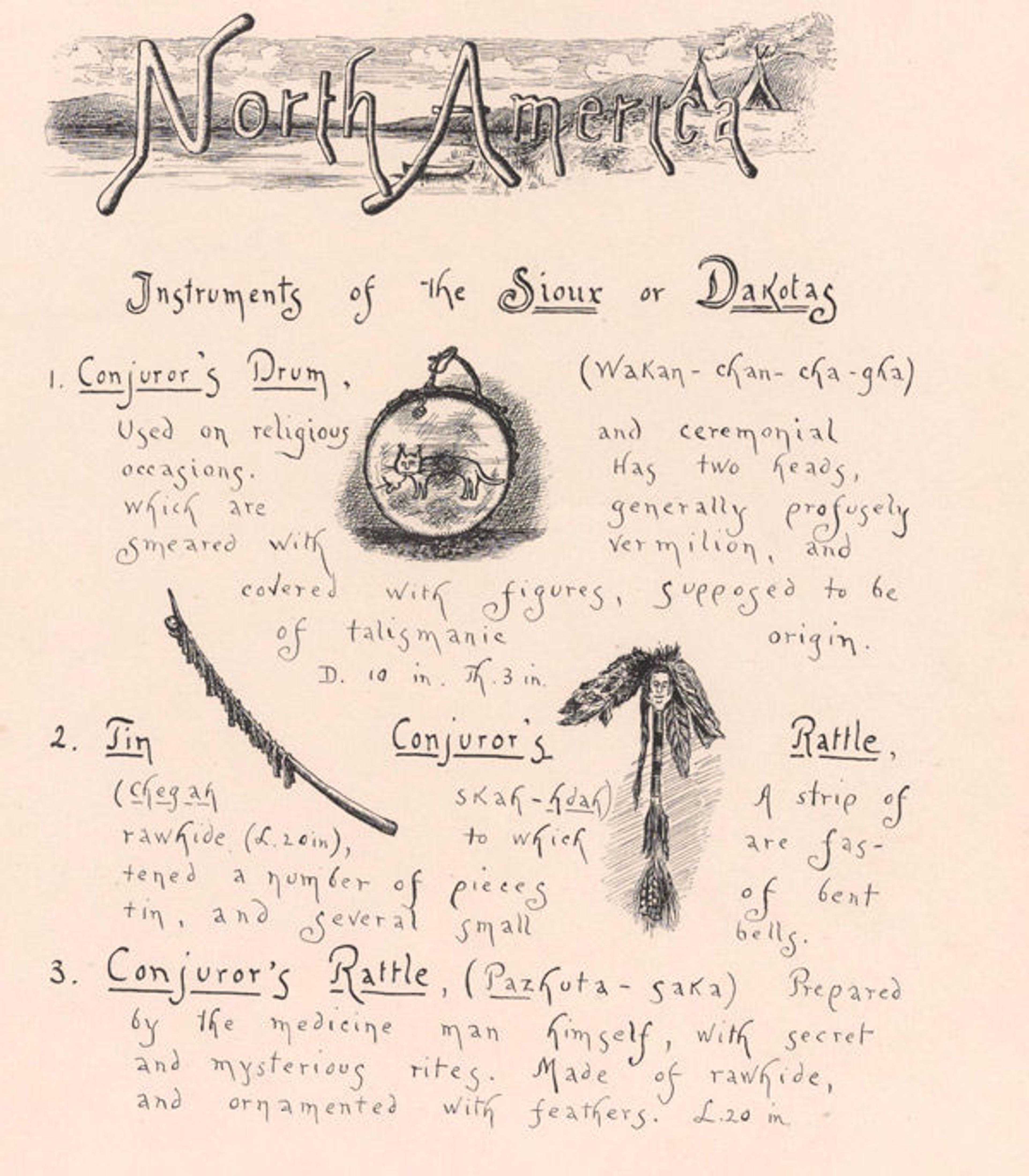

He sent Brown a number of Sioux conjuror's rattles which we can identify, a conjurer's drum with figures, and several other drums, one of which was "sweet tuned" and obtained from a party of Sioux "just returned from a dancing tour, cost $5." For his efforts in helping to establish the North American part of the early Crosby Brown Collection, Sweeny received special acknowledgment in the 1888 catalogue.

Page from Brown's 1888 catalogue, Musical Instruments and Their Homes, featuring instruments collected by Robert Ormsby Sweeny

During her entire collecting career from the mid-1880s until her death in 1918, Mary Elizabeth Brown would acquire American instruments from individual agents, trackers, and missionaries. However, in the 1890s regular accounts of these transactions are less frequent, and her correspondence during this time instead focused on the Far East and Europe as she tried to strengthen those portions of her collection. In the first decade of the twentieth century she would return to her earlier American institutional connections, particularly as the musical expertise of colleagues at the American Museum of Natural History and Smithsonian Institution developed.

Already in the 1880s Dr. Albert Bickmore, anthropology scholar and "scientific founder" of the American Museum of Natural History [AMNH], gave Brown access to the unpublished records of an 1840s coast expedition of Alaska and the Northwest. In addition, Morris K. Jesup—Museum president and close Brown friend—is acknowledged in Brown's final catalogue, published in 1914, as the donor of many American objects. From 1898 to 1902 she also carried on a correspondence with Franz Boas—renowned anthropologist, Northwest Coast Indian authority, and AMNH curator. Brown pestered him for duplicate objects and information about instruments in the Natural History Museum's collections; according to her 1914 catalogue, her perseverance paid off.

Above all, Brown relied most heavily on the curators of the Smithsonian Institution as colleagues and collectors in the musical instruments field. In 1903 she remarkably persuaded General Luigi Palma di Cesnola, the Metropolitan Museum's director, "to borrow" Edwin H. Hawley, curator in the Smithsonian's Anthropology Department to assist with the proper labeling and cataloguing of her Oceaniac and American objects. Hawley was a self-educated, self-effacing, generous genius. As the health of the elder Browns deteriorated, he worked tirelessly with their invaluable associate (later named Museum assistant curator in 1910), Frances Morris. After only a few weeks in New York, Hawley engaged in an intense, regular correspondence with Morris, assisting her until the last Brown catalogue was published over Morris's name in 1914.

Scholarly research, gifts, and exchanges from the Smithsonian abound in that final volume. The Smithsonian also sent reproductions of instruments that had been collected in the field. Like reproductions that Brown received from scholars in Europe, they were meant to represent objects that were not a part of the Museum's collection. An example is an Oolalla (whistle) from the Northwest Coast, the original of which is in the Smithsonian Institution and a copy of which is in the Crosby Brown Collection at the Met. Of particular note are half a dozen intricately carved and beautifully painted talismanic rattles from British Columbian peoples, attributed to James G. Swan as collector.

Swan was an ethnologist, Indian agent, author, and settler in Washington Territory. It is a pleasant coincidence that Brown and Swan, both pioneers in their fields who probably did not know each other, were New Englanders whose families came from the same small Massachusetts town and were distantly related by marriage.

Rattle, 19th century. British Columbia, Canada. Native American (Masseth or Haida). Wood; W. 7 x L. 25.4cm (2 3/4 x 10in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments, 1889 (89.4.647)

Related Links

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: Great Plains Indians Musical Instruments

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: Northwest Coast Indians Musical Instruments

Of Note: Posts related to Mary Elizabeth Brown