«Today the Department of Musical Instruments celebrates its storied history with the launch of A Harmonious Ensemble: Musical Instruments at the Metropolitan Museum, 1884–2014—a comprehensive account of the people, performances, and instruments that have made the department what it is today. This digital publication includes audio and video material dating back to the 1940s, many images of the instruments and the people who have shaped the collection, and original documents never before seen by the public. It is intended as a resource for those interested in the department and its activities, and will also be available, without media files, in a searchable, printable format at a later date.»

Although some of the department's history, notably that of the genesis of the Crosby Brown Collection, is well known, much of the material has not been written about, or has been largely forgotten for many years. I hope that, with this publication, this interesting story will be more widely known. The idea for the departmental history really came about when, in the course of cataloging books in the department's library, I found correspondence files and papers of Frances Morris, who was active at the Museum from 1896 to 1929 and was the first curator with responsibility for the musical instruments. No one remembered that these artifacts were in the library, and, as far as we know, no one had read them for decades.

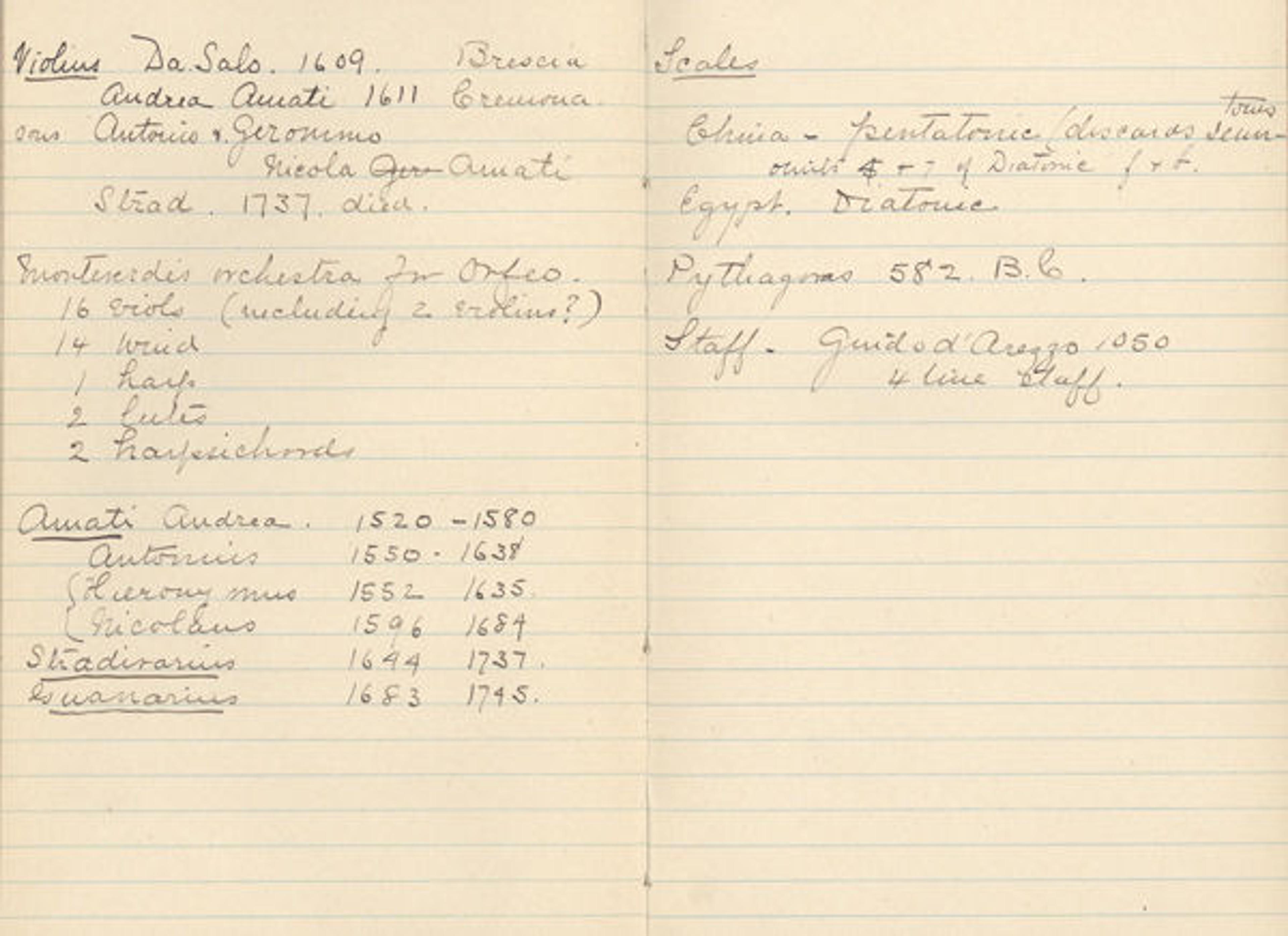

Frances Morris's notes on violins from her "Music Lecture Notes" notebook

While sorting the Morris papers, I began to make a chronological list of important dates and facts, and soon started a narrative of the events thus chronicled. Thanks to support from the Brown family, the department had already done much work with the correspondence of its largest donor, Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown, so it was easy to supplement this with facts relating to the Brown gifts and her work with them before and during the early years of Morris's tenure. Putting the widely known pieces of the Brown history together with the lesser-known contributions of Frances Morris was particularly interesting, as was my research regarding the collection before the Brown donations. Thanks to Joseph Drexel, musical instruments were an important collecting area for the Met beginning 130 years ago, when the Museum's Annual Report noted that the trustees accepted a donation from Drexel of forty-four instruments that he had specifically chosen for the Museum.

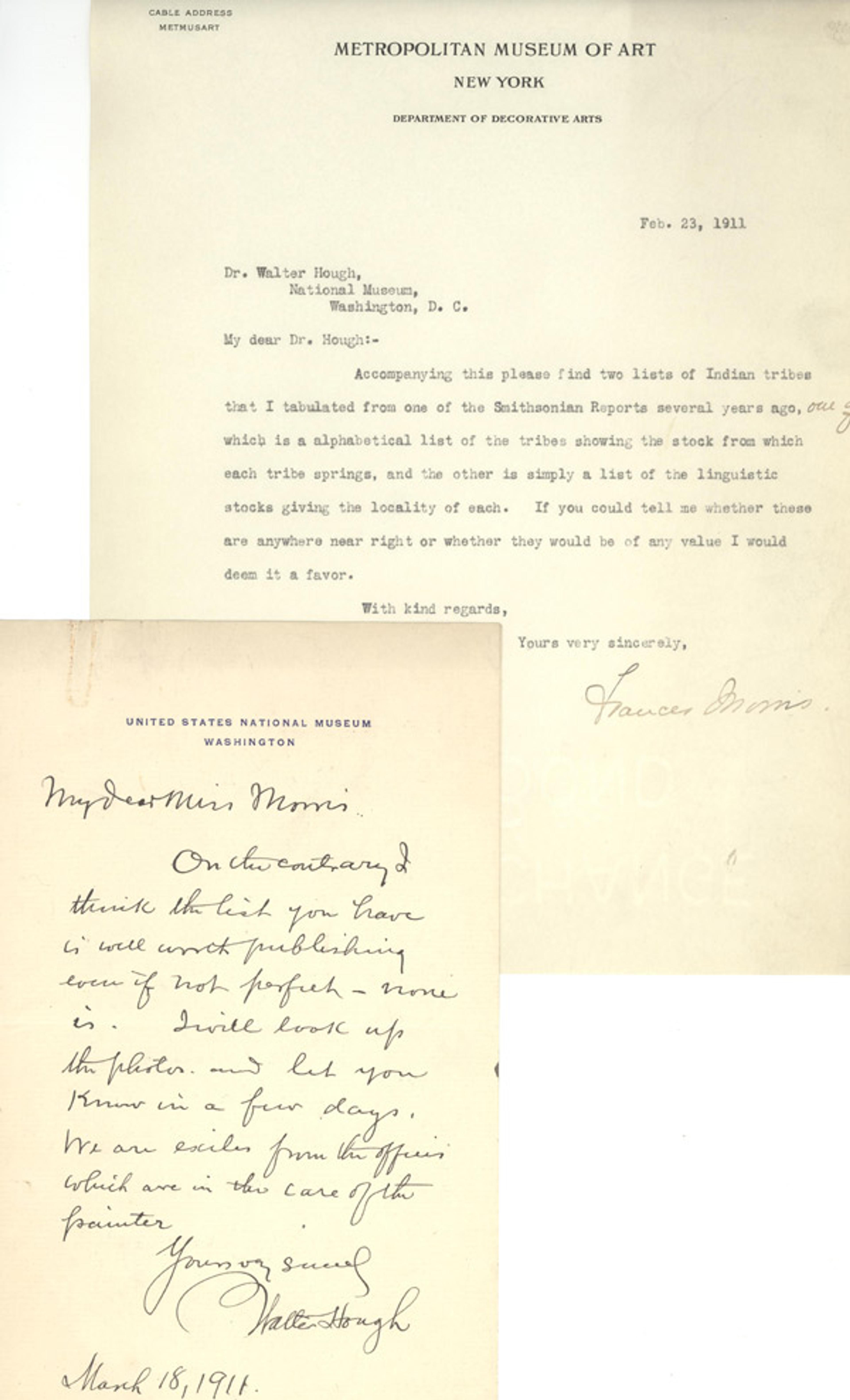

1911 correspondence between Morris and Walter Hough of the National Museum (now the Smithsonian), in which he encourages her to publish her lists of American Indian tribes compiled while cataloguing the Metropolitan's instruments

Putting together the history for the period after Frances Morris's retirement in 1929 highlighted a mystery: Museum guidebooks through 1931 have entries for musical instruments, and Museum maps show musical instruments where Frances Morris arranged them in 1914. Then, nothing: no guidebook published between 1931 and 1945 mentions musical instruments; and the instruments' location is omitted from Museum maps, so that the collection seems to have disappeared. References by Museum officials to musical instruments during the 1930s relate to an unrealized plan to transfer the collection to the Julliard School and/or the New York Public Library, for use by students.

The answer to this mystery came from a great piece of good fortune. While I was working on the early history of the musical instruments collection, the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts contacted the Department of Musical Instruments. Their longtime curator, Dr. Olga Raggio, had died in 2008, and staff who had been reviewing her files identified several cabinets as containing papers of Dr. Emanuel Winternitz. Employed by the Museum from 1941 to 1983, Winternitz was the curator who presided over the formal establishment of the Department of Musical Instruments and Concerts (as it was initially known) in 1949. Raggio—like Winternitz, a European scholar—immigrated to the United States in 1950 from war-torn Italy to take up a position as a Museum fellow, and the two were close friends until Winternitz's death.

The new Winternitz files revealed that he had left at the Museum, in Raggio's care, not only the numerous drafts of the autobiography he was writing at the time of his death, but also his personal and professional correspondence from the time he arrived in the United States until he died. More remarkably, he had also left with her personal papers that included thousands of documents of his life in Vienna from 1898 to 1938. Among these were family photographs, school books, and drawings.

A selection of Winternitz's concert tickets from his time in Vienna, and the envelope where he kept them

These Winternitz papers were unknown to the curatorial staff, and made it possible to write an account of this period of the department's history with this newly found information. Among other things, the papers solved the mystery of what happened to the instruments during the 1930s, as Winternitz's writings made it clear that the Museum had not moved the instruments, but rather shuttered the 1914 galleries in about 1931. They were closed to the public and treated as storerooms. Winternitz "found" the instruments when he arrived in 1941, and in 1942 began bringing them back to permanent public display.

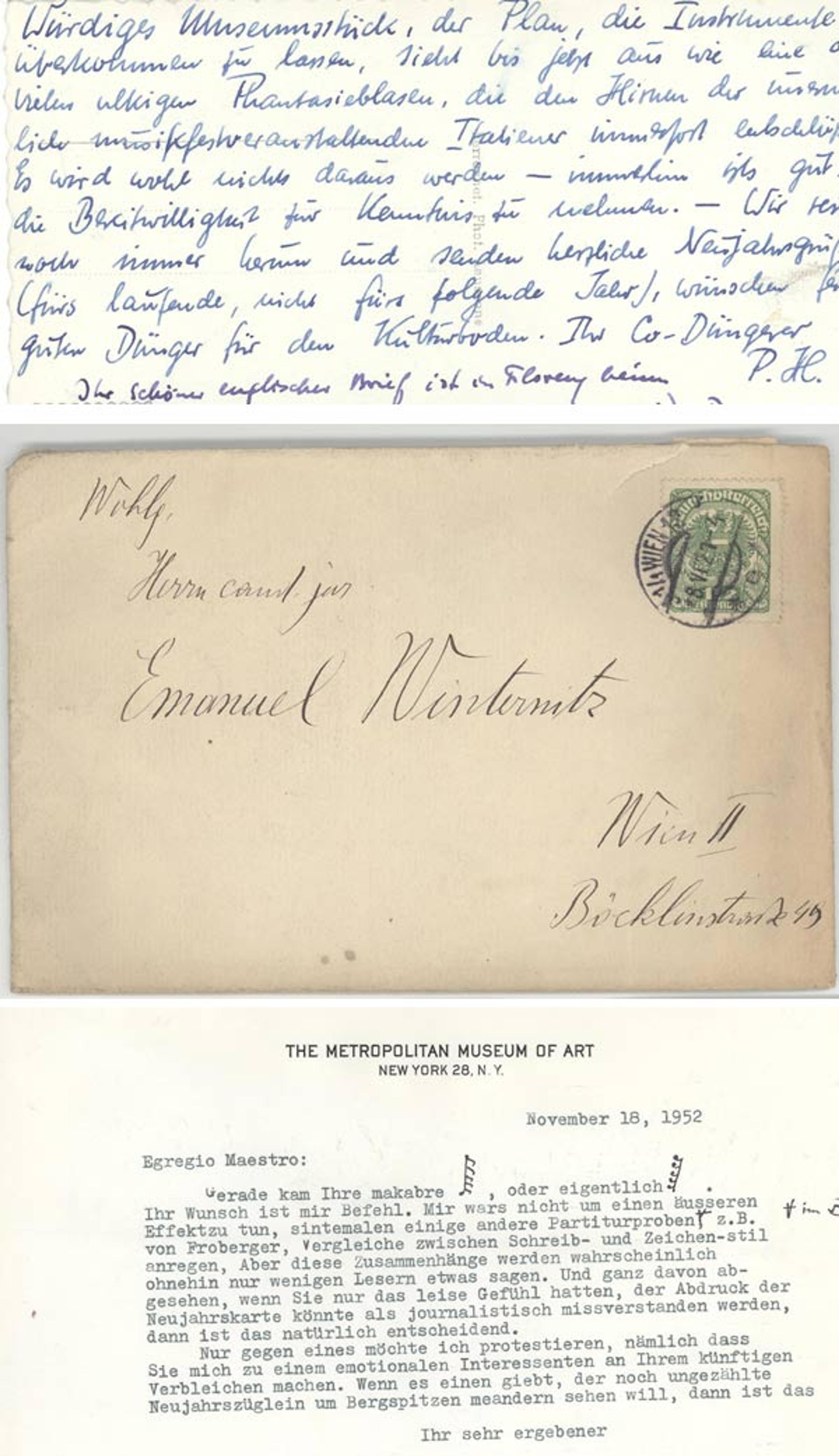

Correspondence between Winternitz and his lifelong friend, the conductor Paul Hindemith. Winternitz often wrote in German or Italian, and sometimes in French, as well as in English, and often mixed languages in one letter.

Another aspect that contributed to the history was the identification and digitization of many archival recordings related to the instruments. For several decades, before and after it became a formal curatorial department, Musical Instruments was responsible for all of the Museum's musical performances. Frances Morris gave the Museum's first radio broadcast about the instrument collection (only the second broadcast in the Museum's history) in 1926, but no copy of that is known to exist. Sadly, no recordings of the Museum concerts conducted from 1917 to 1947 by David Mannes exist either, although in the later years those concerts were broadcast live throughout the Museum on a public-address system underwritten by Thomas J. Watson.

It was Emanuel Winternitz who embraced the possibilities that the advancement of recording technology gave to the collection. I came across a newsreel made in 1943 when Winternitz opened new galleries of European instruments, and the Museum's Information Technology department was able to restore the sound. Stacks of brittle lacquer discs in various formats were digitized through the kindness of Andy Lanset of WNYC, and proved to be recordings of Member concerts organized by Winternitz during the 1940s and 1950s. In many of the concerts, Winternitz provides commentary that is of great interest, since the concerts are now recognized as seminal to the history of the early music movement in the United States. In some cases the instruments from the collection played on the recordings are no longer playable, so the recordings are a unique archive.

A Harmonious Ensemble was made possible by the courtesy and assistance of myriad Museum staff across the Museum Archives, the Watson Library, the Departments of Musical Instruments and European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, and in Design, Information Technology, and Digital Media, to all of whom I am indebted. It is my hope that it will both be useful to researchers and curators, and will be as much fun to read as it was to write.

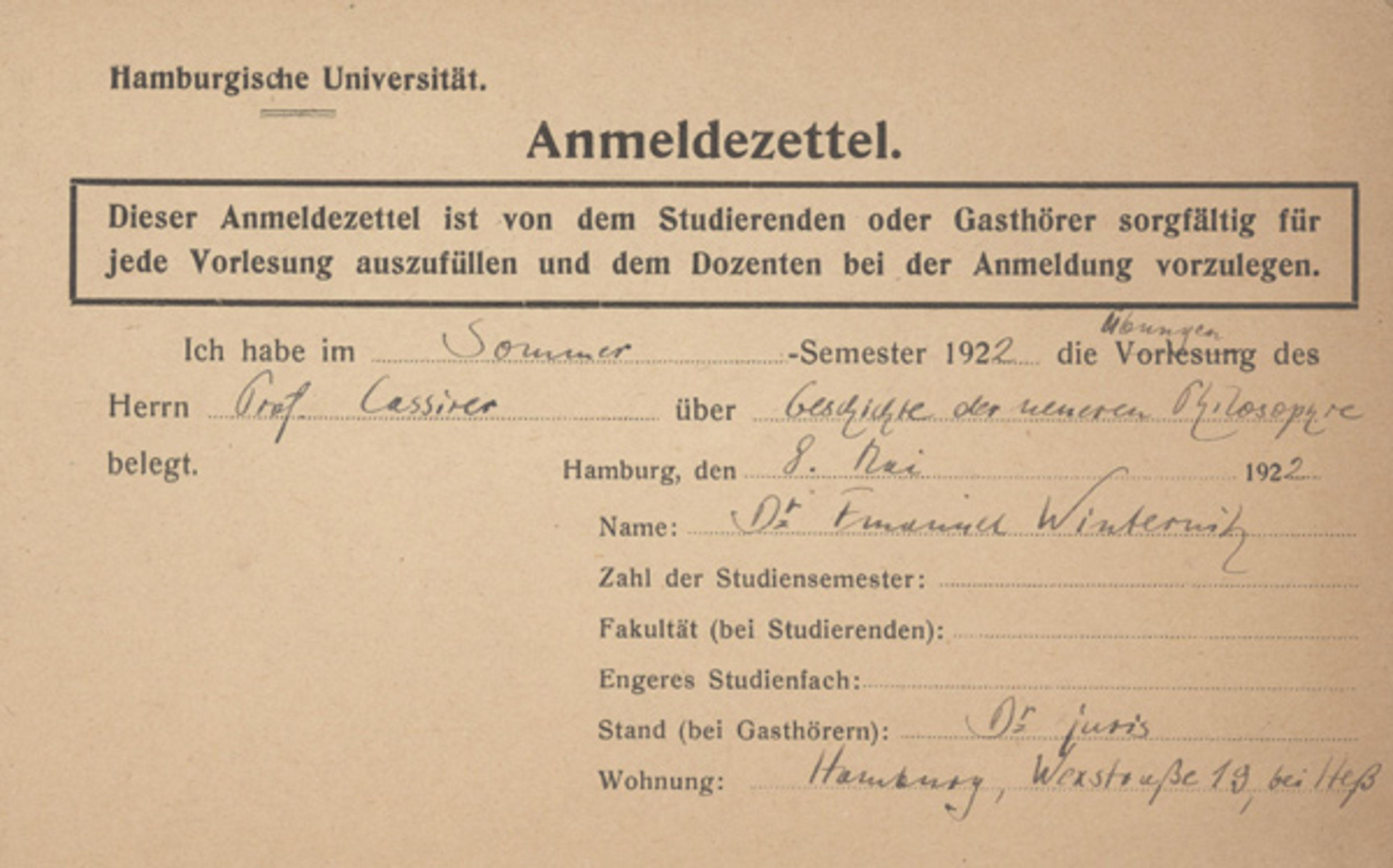

Winternitz's 1922 University of Hamburg registration for a seminar with the eminent philosopher Ernst Casirer, who also emigrated to the United States and maintained correspondence with Winternitz until his death in 1945. This class prompted Winternitz's lifelong interest in the symbolism of art and music.

A Harmonious Ensemble: Musical Instruments at the Metropolitan Museum, 1884–2014