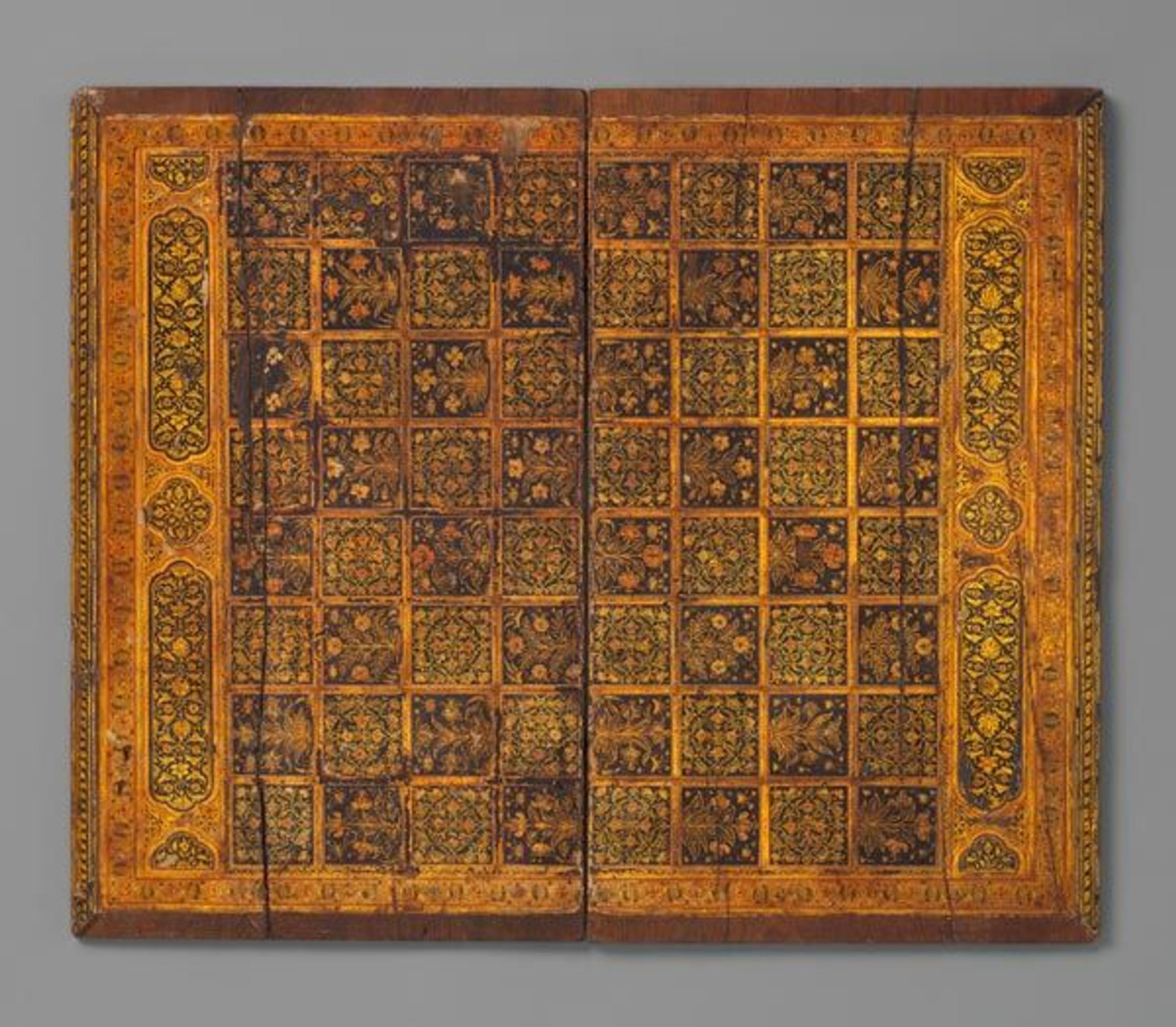

Floral gameboard, late 17th century. India. Islamic. Wood; painted, varnished and gilded; with metal hinges; H. 17 1/4 in. (43.8 cm) x W. 14 3/8 in. (36.5 cm) D. 1/4 in. (0.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Louis E. and Theresa S. Seley Purchase Fund for Islamic Art and Rogers Fund, 1983 (1983.374)

«When the Department of Islamic Art prepared for the opening of Sultans of Deccan India, 1500–1700: Opulence and Fantasy, on view through July 26, there was a great deal of movement in the permanent galleries as certain objects from the collection traveled to their temporary home in gallery 199. Gallery 463, which showcases art from Mughal South Asia and later South Asia, was particularly affected by these shifts in location, and some fascinating new items have gone on display in this gallery.»

Among the new objects is a hinged wooden gameboard from the late seventeenth century. This gorgeous board is two-sided, featuring a chess board painted on one side and a backgammon table on the other. Made of wood that was painted, varnished, and then gilded, the board was meticulously decorated with minute details, likely by an artist who had been trained in preparing bindings for manuscripts. One of the interesting details that the artist included was the variation in flowers; one set of squares in the chess grid is made up of eight different flower varieties.

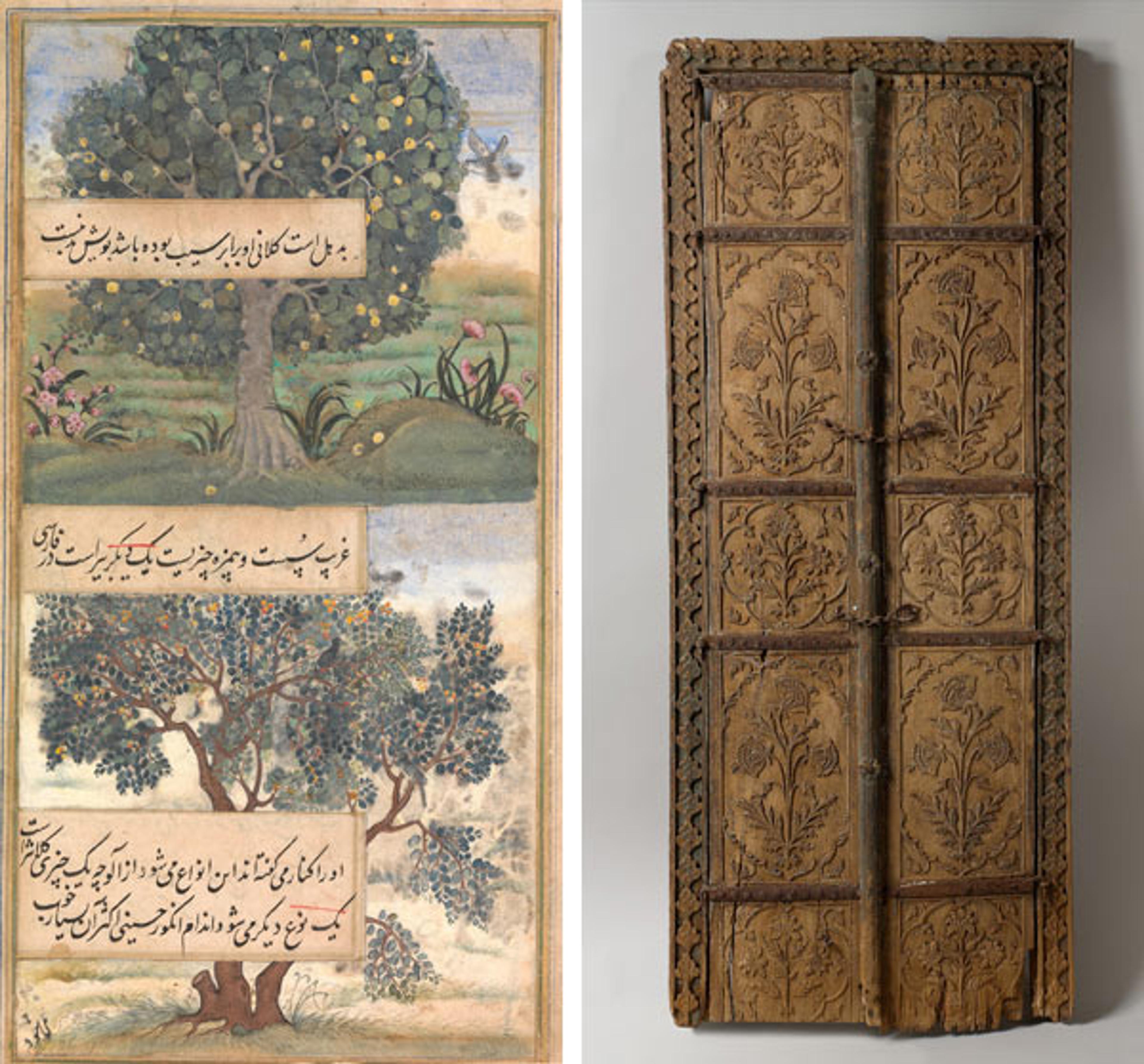

The Mughals were very interested in the natural world. In fact, Babur (r. 1526–30), the founder of the Mughal dynasty, devoted significant portions of his memoirs, the Baburnama (Autobiography of Babur), to descriptions of the flora and fauna he encountered in Central and South Asia. These descriptions were picked up by artists in his grandson Akbar's (r. 1556–1605) workshop, where multiple manuscripts of the Baburnama were produced. A folio from one of these manuscripts in the department's collection depicts three trees of India that are described in accompanying text (below left).

Left: "Three Trees of India," folio from a Baburnama (Autobiography of Babur), late 16th century. India. Islamic. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper; H. 9 13/16 in.(25 cm) x W. 5 1/8 in. (13 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Louis E. and Theresa S. Seley Purchase Fund for Islamic Art, Anonymous Gift, in honor of Amy Poster, and Friends of Islamic Art Gifts, 2013 (2013.576). Right: Pair of flower-style doors, second half of the 17th century. Northern India. Islamic. Wood; carved with residues of paint; H. 73 in. (185.4 cm) x W. 30 in. (76.2 cm) includes both doors; D. 3 in. (7.6 cm); Wt. 63 lbs. (28.6 kg). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Harvey and Elizabeth Plotnick, 2009 (2009.376a, b)

Akbar's son Jahangir (r. 1605–27), who styled himself after Babur, followed in this tradition in his memoirs, the Jahangirnama. It was at this time that Mughal images started to reflect the presence of European art in India, and the style found in vegetal imagery of the time indicates probable access to botanical texts from Europe. This introduction soon took on a life of its own in Mughal arts and can be observed in different media—such as in the pietra dura inlay at the Taj Mahal, or in the pair of flower-style doors (above right) on display next to the gameboard. To come full circle, the late eighteenth century saw a new genre of botanical illustrations that were often commissioned by the British in India as records of local specimens, echoing Babur's interest in his surroundings.

It's an unexpected bonus of large exhibitions that we have the opportunity to display different objects from the department's permanent collection. We hope you'll visit the galleries in the coming weeks to view these treasures while they are on view.