Mural

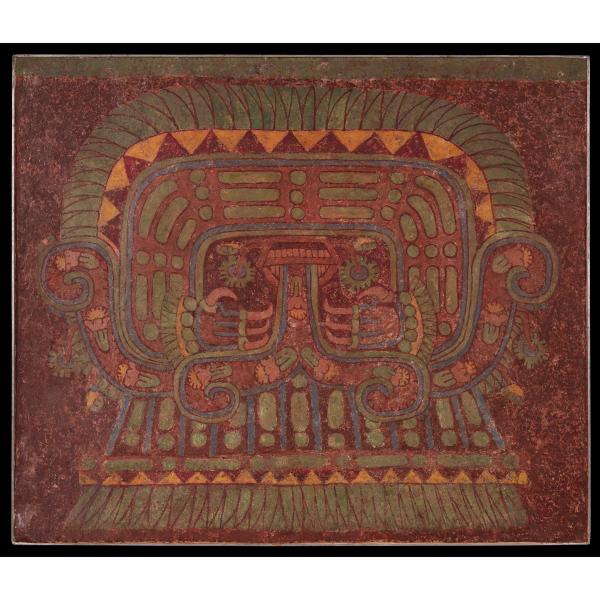

The fragment shows a highly abstract depiction of what may be a deity, or perhaps even an elaborate, undeciphered hieroglyphic logogram (a sign representing a word). The symmetry of the figure and the location of a toothed mouth and clawed hands suggest a stylized anthropomorphic being. From the mouth emerges scrolls covered in images of flowers, perhaps a visual representation of "flowery speech" or benevolent oration. The figure is covered in circular and ovular shapes painted green—mostly likely images of jade beads—and fringed with green feathers; both greenstone and green feathers were luxurious imported materials. The green color evokes water, maize plants, and agricultural fertility.

A similar fragment is in the collections of the Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts, and a fragment of the same mural series in the Ethnological Museum in Berlin includes a border that repeats the jade and feathered motifs. Not all aspects of the mural's central character are flowery and green, however: the fearsome claws at the center of the image hint at the threat of potential violence by natural forces, divine power, or Teotihuacan’s own military regime.

Further Reading

Berrin, Kathleen, and Esther Pasztory. Teotihuacan: Art from the City of the Gods. The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1993.

Carballo, David M., Kenneth G. Hirth, and Barbara Arroyo. Teotihuacan: The World Beyond the City. Dumbarton Oaks, 2020.

Cowgill, George L. State and Society at Teotihuacan. Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 26, pp. 129-161, 1997.

Evans, Susan Toby, "Teotihuacan Murals: An Appendix," in Processions in the Ancient Americas, Penn State University Occasional Papers in Anthropology No. 33 (2016): 122–153

Galitz, Kathryn. The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Masterpiece Paintings. New York: Skira, 2016, no. 44.

Headrick, Annabeth. The Teotihuacan Trinity: The Sociopolitical Structure of an Ancient Mesoamerican City. University of Texas Press, 2007.

Manzanilla, Linda R. Cooperation and tensions in multiethnic corporate societies using Teotihuacan, Central Mexico, as a case study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America Vol. 112, No. 30, pp. 9210-9215, 2015.

Murakami, Tatsuya. Entangled Political Strategies: Rulership, Bureaucracy, and Intermediate Elites at Teotihuacan. In Sarah Kurnick and Joanne Baron, eds., Political Strategies in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, pp. 153-179. University Press of Colorado, 2016.

Pasztory, Esther. Teotihuacan: An Experiment in Living. University of Oklahoma Press, 1997.

"Recent Acquisitions: A Selection 2014." In Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. Vol. vol. 72, no.2. Fall 2014, p. 15.

Robb, Matthew, ed. Teotihuacan: City of Water, City of Fire. San Francisco: de Young Museum, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2017, no. 180, p. 410.

Ruiz Gallut, María Elena, and Jesús Torres Peralta, eds. Arquitectura y urbanismo: pasado y presente de los espacios en Teotihuacan: Memoria de la Tercera Mesa Redonda de Teotihuacan. Mexico City, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 2005.

Sarro, Patricia J., and Matthew H. Robb. Passing through the Center: The Architectural and Social Contexts of Teotihuacan Painting. In Cynthia Kristan-Graham and Laura M. Amrhein, eds., Memory Traces: Analyzing Sacred Space at Five Mesoamerican Sites, pp. 21-43. University Press of Colorado, 2015.

Sugiyama, Saburo. Human Sacrifice, Militarism, and Rulership: Materialization of State Ideology at the Feathered Serpent Pyramid, Teotihuacan. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Taube, Karl A. The Temple of Quetzalcoatl and the Cult of Sacred War at Teotihuacan. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, No. 21, pp. 53-87, Spring, 1992.

Turner, Andrew. Unmasking Tlaloc: The Iconography, Symbolism, and Ideological Development of the Teotihuacan Rain God. In Anthropomorphic Imagery in the Mesoamerican Highlands: Gods, Ancestors and Human Beings, Brigitte Faugere and Christopher S. Beekman, eds. University Press of Colorado, 2020.

Artwork Details

- Title: Mural

- Artist: Teotihuacan artist(s)

- Date: 500–550 CE

- Geography: Mexico

- Culture: Teotihuacan

- Medium: Earthen aggregate, lime plaster, pigments

- Dimensions: H. 25 3/4 × W. 30 3/4 × D. 1 1/2 in., 69 lb. (65.4 × 78.1 × 3.8 cm, 31.3 kg)

- Classification: Paintings-Frescoes

- Credit Line: Gift of John and Marisol Stokes, 2012

- Object Number: 2012.517.1

- Curatorial Department: The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Audio

1634. Mural, Teotihuacan artist(s)

Diana Magaloni and David Carballo

DIANA MAGALONI: Teotihuacan mural paintings are always placed against a very dark red background. It’s as though they are emerging from this red background.

JOSÉ MARÍA YAZPIK (NARRATOR): This fragment of mural comes from an apartment in the city of Teotihuacan, one of the greatest cities of the ancient world.

DIANA MAGALONI: The Art of Teotihuacan presents a series of concepts, and it could be thought of as almost painted language. My name is Diana Magaloni. I am the head of the Art of the Ancient Americas at L.A. County Museum of Art.

JOSÉ MARÍA YAZPIK: Look closely and you’ll see a mouth with a forked, scrolling tongue. The figure has jaguar claws and is adorned with jade beads.

DIANA MAGALONI: That is signifying the preciousness of life because jade is petrified water. And it's also petrified breath, the breath of life, the freshness of water. All of these elements tells us that, very likely, the Divine figure relates to the storm God, or Tlaloc in Nahuatl.

JOSÉ MARÍA YAZPIK: Such images are closely associated with divinity, luxury and power, evoking Teotihuacan’s position as the center of an empire.

DAVID CARBALLO: It served as a political capital, a economic hub, and a religious center or a pilgrimage center for Central Mexico, and indeed, for larger parts of Mesoamerica.

JOSÉ MARÍA YAZPIK: David Carballo, Boston University.

DAVID CARBALLO: I think we can really draw some analogies between Teotihuacan and New York City. It was a cosmopolitan city. Multiple languages were spoken there, and it attracted migrants from all around Mesoamerica. It featured ethnic enclaves that migrant communities would use as anchors as they arrived to the city. The large majority of the occupants of the city lived in multi-family apartment compounds.

JOSÉ MARÍA YAZPIK: At the height of its power, the city covered 16 square miles and was home to 100,000 people. The painted walls of this vibrant city gleamed in the sunlight and glimmered at night, by torchlight.

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.