Introduction

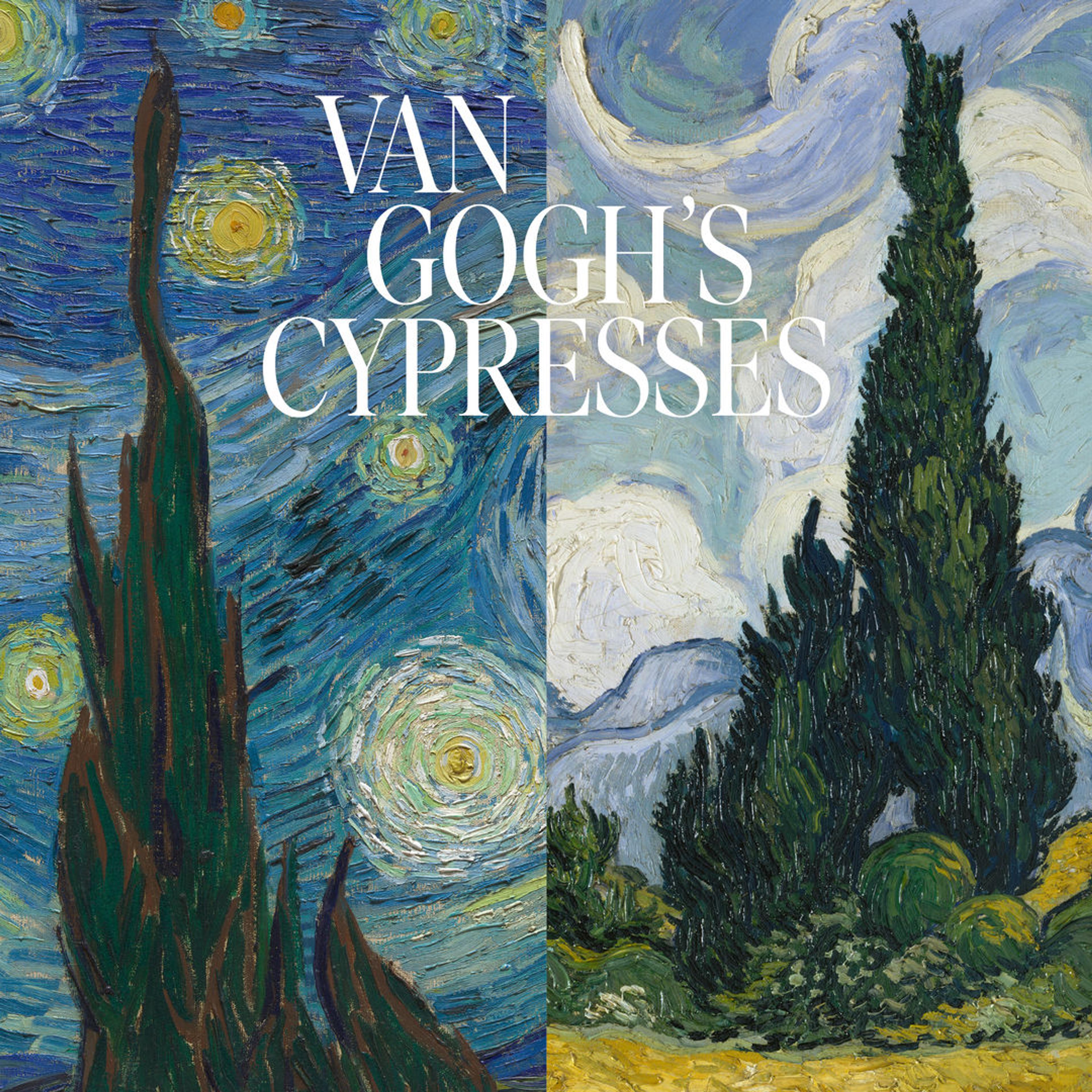

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) had an uncanny knack for getting to the root of the matter. Folding his initial thought on cypresses into a letter of April 1888 from the South of France, the Dutch artist sized up the potential he foresaw—and famously realized—of picturing the region’s distinctive evergreens under star-strewn night skies or above golden fields of wheat. Yet it was not until more than a year later, after he left the Provençal town of Arles to take refuge at the nearby asylum of Saint-Rémy, that this spark of inspiration gave rise to his iconic pictures of the flamelike trees. Those epic works—part of a short-lived but momentous painting campaign in June 1889 typically lauded as his “discovery” of the cypress—take their place in a presentation that fills in the backstory of his invention for the first time.

Following the arc of Van Gogh’s progressive exploration of the towering evergreens, as they gained ground in his artistic thinking over the course of his two-year sojourn in Provence, this thematic survey retraces his long-standing preoccupation with a motif that he found captivating and challenging in equal measure. Astonished “that no one has yet done them as I see them,” he prevailed to give signature form to the cypresses in works as striking for their originality as for their continuity of vision—from his first inspired response to the trees, in his only dated drawing from Arles, to his “last try” at satisfying his ambition, in a studio composition painted just before he left the asylum in May 1890.

The Roots of His Invention

Arles, February 1888–May 1889

After two years in Paris, Van Gogh made his way to the town of Arles, primed to invest his art with “the rich color and rich sun of the glorious south” in the spirit of “true colorists” he admired, who “give us something passionate and eternal.” He was destined to immortalize the region’s celebrated cypress trees in precisely these terms.

The most eye-catching and storied fixture of the Provençal countryside immediately struck a chord with the Dutch artist. He was quick to express the “need” to lay claim to the cypresses and to reserve a place for them in his repertoire. The robust, long-living evergreens not only carried age-old associations with death, rebirth, and immortality, but also had presided over the region for millennia, standing guard in their revered role as protectors of a landscape impacted by the notoriously fierce northerly mistral winds. Few motifs were more emblematic of the South of France or resonated more strongly with his profound appreciation for the enduring and consoling aspects of nature.

From the time he found his footing in Arles, hoping that his Provençal outpost would attract other artists, until the fateful arrival of Paul Gauguin that fall, Van Gogh explored the evocative potential of incorporating this “interesting dark note” in sun-drenched landscapes marked by their ambition. His initial investigations of the cypress motif speak to the rich dialectic between observation and reflection that grounded his practice: “To find the real character of things here, you have to look at them and paint them for a very long time.”

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

The Making of A Signature Motif

Saint–Rémy, May–September 1889

In May 1889, Van Gogh took refuge at the asylum in Saint-Rémy. Nestled in the foothills of the Alpilles, the former monastery placed him in a dramatic setting, more rustic and rugged than the flat, cultivated landscape of nearby Arles. Under the care of doctors (who diagnosed his condition as a form of epilepsy) and allotted a spare room to use as a makeshift studio, the artist forged ahead at a staggering pace, slowed only by hospital restrictions, depleted or embargoed supplies, and recurrent breakdowns that periodically brought his efforts to a halt.

Once he was granted permission, in June, to explore the rolling countryside beyond the walls of the asylum, Van Gogh advanced a painting campaign that he revisited in equally dynamic drawings. This initiative represented his most formidable and concerted effort to tackle the cypresses in earnest. In swift, confident succession, with increasing intensity, he homed in on the gravely majestic trees in a half-dozen landscapes. Van Gogh drew upon both studies from nature and studio invention as he torqued earlier preoccupations into place, evolving a forceful style of expression that wed evocative color with anti-naturalistic line in rich passages of impasto. As a signpost of the region and a beacon of hope, perseverance, and resilience, the cypress was bound to enjoy particular resonance during this chapter in his career. It admirably served as a vehicle to satisfy aspirations on various levels, with the potent motif fostering an approach that measured up to the grander side of nature and his own ambitions.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Branching Out In Style

Saint–Rémy, October 1889–May 1890

After battling back from a mid-July breakdown in the quiet of his studio, Van Gogh returned to painting out of doors in the fall armed with fresh impetus and resolve. He envisioned his work would form “a kind of ensemble, ‘Impressions of Provence’” anchored by emblematic motifs. Setting his sights on giving renewed focus to the cypresses, along with the olive trees and the mountains, with an eye to extracting their true character and investing them with greater linear verve, he vowed to soldier on at the asylum: “It’s difficult to leave a land before having something to prove that one has felt and loved it.”

When it came to the cypresses, Van Gogh’s pledge to “do them as I feel [them]” proved easier said than done. Despite the ambition he confided to works made that October and voiced in a litany of later letters, his “great desire” to tackle the motif anew was variously diffused, derailed, and, by his own admission, daunted by powerful “emotions that take hold of me in the face of nature.” The cypresses failed to gain traction in plein air, while continuing to preoccupy and even haunt his thoughts.

This provocative last chapter highlights the nature of Van Gogh’s art as a work in progress, spurred along by his trademark determination and resourcefulness. He navigated a shortfall of painting supplies by exploring new stylistic territory and, ultimately, the “enchanted ground” of working from the imagination—rising to the challenge, in May 1890, with the means at his disposal, to sign off on the cypress motif in inimitable form.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.