Kneeling female figure with three children

In the absence of scientific testing, this work is broadly dated to sometime between the 15th and early 20th centuries and is attributed to the Tellem-Dogon peoples. European authors have conducted research among the Dogon peoples in the Bandiagara Escarpment (Mali) since 1903, when sculptures such as this started to enter Western collections. In their oral accounts to Western scholars, the Dogon recounted that they had migrated to the region in the 15th century. At their arrival, they discovered that another population, the “Tellem”— literally, ‘we have found them here’—had lived there since the 11th century and eventually disappeared for unknown reasons. More recently, ethnographic and archeological investigations have confirmed the existence of a ‘Tellem’ population, one that pre-dated and was distinguished from the Dogon. Through radiocarbon analysis of objects and burial sites, specialist Rogier Bedaux delineated a chronology of the populations who lived in the Bandiagara Escarpment: Tellem (11th-15th century), Tellem-Dogon (15th-17th century), Dogon (17th-20th century). While this specific sculpture has yet to undergo scientific testing, it probably belongs to the second phase (Tellem-Dogon) when these two groups lived side-by-side influencing each other’s customs and artistic practices. Indeed, this sculpture displays formal qualities found in both Tellem and Dogon works. For instance, its patina and stylized forms can be seen in earlier Tellem objects, whereas the motif of the kneeling woman with thin limbs recalls later Dogon statuaries.

The figure of the kneeling mother holding her children has been an important subject of religious sculpture in the region. While we do not have written or oral accounts from the Tellem populations, field research conducted during the early 20th century among the Dogon may provide some clues on this sculpture’s original significance. Dogon patrons commissioned similar maternity figures to express a prayer to be blessed with children. Placed on altars, these sculptures would function as a surrogate for their patron and as an expression of their prayer. Yet, while these works typically represent a female figure holding one or two infants, in this specific case, the sculptor included three: one in the front and two identical ones on her back. The pairing on the back suggests that they are not only siblings but also twins. Twins are frequently represented in sculptures among different ethnic groups across the continent including the Yoruba and the Luba. Among the Dogon, the depiction of twins has often been described as a reference to a myth of origin recorded by anthropologist Marcel Griaule in 1948 in his conversation with the elder Ogotemmêli. In this Tellem-Dogon piece, the sculptor combines imagery of motherhood and twinness producing a particularly charged object, one that speaks to the patron’s intimate yearning and a society’s beginnings.

The sculpture’s surface also provides important information concerning its ritual use. Carved from one piece of wood, the sculpture is fully covered with a thick application of organic matter. This grainy substance homogenously covers the statue revealing—rather than concealing—its volumes and forms. In their research on the chemical composition of such applied surfaces, scientists have found that they are composed of animal blood and millet. While both Tellem and Dogon sculptures feature thick patinas, their different colorations and textures suggest that there were variations to these practices. These semi-liquid substances could for instance be applied either through hand-coating or by dipping. In some cases there are multiple layers indicating that this procedure was repeated for individual sculptures. Among the Dogon the patina played the role of receptacle for nyama, or life force. Without this substance and its ritual appliance, the statue would be a mere piece of wood devoid of any protective power. The patina thus becomes a crucial component in appreciating this sculpture and its ceremonial significance.

Giulia Paoletti, Andrew W. Mellon Curatorial Postdoctoral Fellow, 2017

Published References

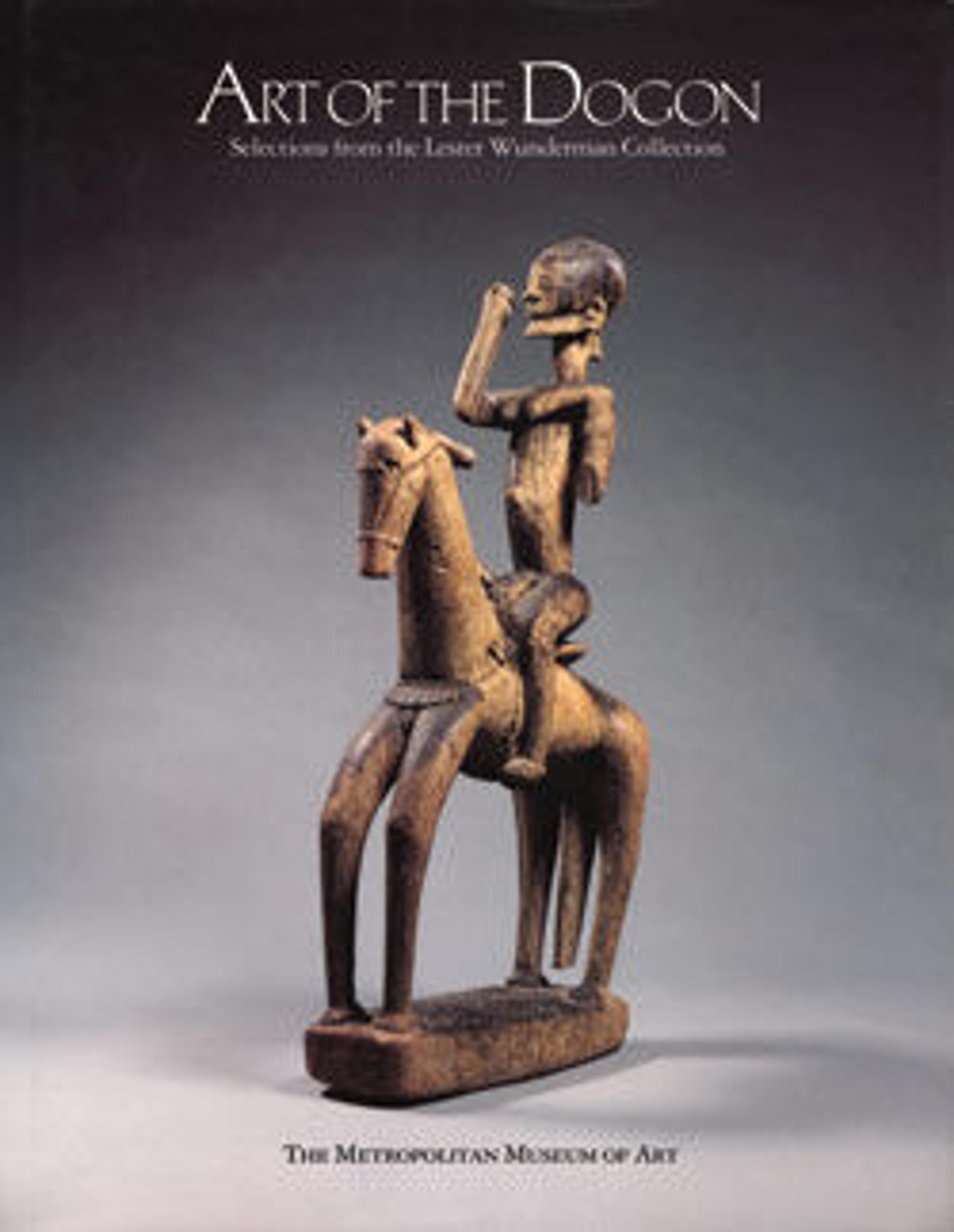

Ezra, Kate. 1988. Art of the Dogon: Selections from the Lester Wunderman Collection. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 48-49

Laude, Jean. 1973. African Art of the Dogon: The Myths of the Cliff Dwellers. New York: Brooklyn Museum. no. 56.

Further Reading

Leloup, Hélène. 2011. Dogon. Paris: Somogy, Musée du quai Branly. Mazel, V., Richardin P., Debois D., Touboul D., Cotte M., Brunelle A., and Walter P. 2008. “The Patinas of the Dogon-Tellem Statuary: A New Vision through Physico-chemical Analyses.” Journal of Cultural Heritage, 9, pp. 347-353.

Peek, M. Philip. 2011. Twins in African and Diaspora Cultures: Double Trouble, Twice Blessed. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Van Beek, Walter E. A. 1988 "Functions of Sculpture in Dogon Religion." African Arts 21, no. 4, pp. 58-65, 91.

Artwork Details

- Title: Kneeling female figure with three children

- Artist: Tellem or Dogon blacksmith

- Date: 15th–19th century

- Geography: Mali

- Culture: Dogon or Tellem peoples (?)

- Medium: Wood, applied organic materials

- Dimensions: H. 13 x W. 3 x D. 2 5/8 in. (33 x 7.6 x 6.7 cm)

- Classification: Wood-Sculpture

- Credit Line: Gift of Lester Wunderman, 1977

- Object Number: 1977.394.21

- Curatorial Department: The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Audio

1530. Kneeling female figure with three children, Tellem or Dogon blacksmith

Pierre Thiam

PIERRE THIAM: It's a missed opportunity to stop by a sculpture like this kneeling woman and just see a kneeling woman. You know, there’s so much more than that at play here.

ANGELIQUE KIDJO (NARRATOR): This sculpture is carved from wood, but it's encrusted in a thick, pebbly layer of porridge. Senegalese chef and social activist Pierre Thiam.

PIERRE THIAM: That porridge represents the gift that the ancestors have given to our people for thousands of years. We pray for a good harvest, and when the good harvest comes, we give it back to the ancestors.

ANGELIQUE KIDJO: The porridge was probably made with fonio, an ancient staple grain for the people who offered it in sacrifice.

PIERRE THIAM: Fonio, it’s from the millet family. It could be the oldest cultivated grain in Africa. The Dogon people believe it to be the seed of the universe.

These grains are not just seen as simple food. They also see it as a weapon really against evil eye and a way to connect with the spiritual world. So that grain often comes in rituals, in sacrifices, and in offerings, and in the way of honoring the guests as well. It is the tiniest and mightiest of all grains.

###

Audio credit: The villagers of Djuiguibombo. From Dama in Djiguibombo Village, Mali (March 2010), courtesy of Polly Richards.

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please complete and submit this form. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.