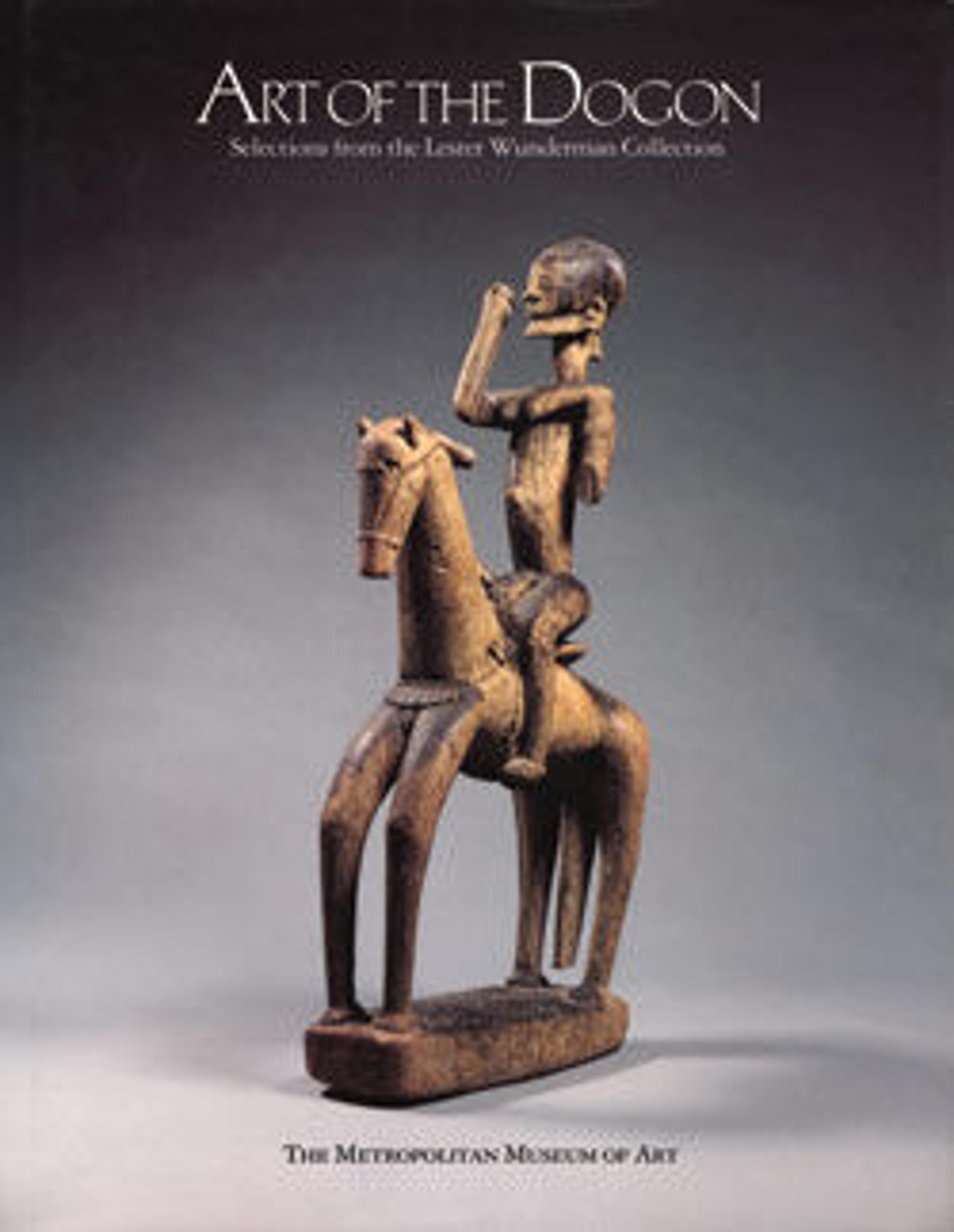

Male figure

The populations of the ancient states of Ghana and Takrur, situated west of the Niger River, were predominantly composed of Soninke speakers, who are credited with establishing trade routes in the interior of West Africa. At the start of the second millennium CE, a series of developments—including the conquest of ancient Ghana, the opening of new gold fields along the frontier of present-day Mali and Guinea, and severe droughts—led the Soninke to venture farther south. Their interactions with Bamana and Malinke communities stimulated trade networks and led to the formation of new states. Some Soninke communities likely resettled in the nearby Bandiagara Escarpment, where they engaged with established Tellem and Dogon groups. This work is among the sculptural figures with pronounced facial features, braided coiffures, and elaborately patterned textiles produced by Soninke blacksmiths living on the plateau.

Artwork Details

- Title: Male figure

- Artist: Soninke blacksmith

- Date: 13th century

- Geography: Mali

- Culture: Soninke peoples (?)

- Medium: Wood, oil

- Dimensions: H. 25 3/8 x W. 3 7/8 x D. 4 5/8 in. (64.5 x 9.9 x 11.8 cm)

- Classification: Wood-Sculpture

- Credit Line: Gift of Lester Wunderman, 1985

- Object Number: 1985.422.2

- Curatorial Department: The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Audio

1531. Male figure, Dogon blacksmith

Roderick McIntosh

ANGELIQUE KIDJO (NARRATOR): Oral traditions have played a critical role in the transfer of knowledge in many African societies. This depiction of a bearded elder holding a wooden staff over his shoulder is a material artifact of the deep history that unfolded in present-day Mali. Archaeologist Roderick McIntosh, Professor emeritus at Yale University, summarizes the standard narrative of events, according to the oral traditions.

RODERICK MCINTOSH: At the decline of the Ghana Empire, sometimes put between the eighth century AD and the tenth century AD, there was waves of people called Soninke who moved out of the core area for the Empire of Ghana, which would have been what’s the southern Sahara now.

The Dogon say they started in an area called Mande, around the border between Guinea and Mali. And at the end of the Mali Empire, so this is going back to the fifteenth century, the traditions are that they either moved right into the escarpment itself and found the Tellem there, or they stayed for some time in the middle Niger.

ANGELIQUE KIDJO: Sifting through different forms of information, the research of scholars such as McIntosh seek to reconcile physical forms of evidence with these oral histories.

RODERICK MCINTOSH: I think there’s an argument to be made as an alternative to that standard chronology, which was basically the Dogon have been living there without interruption for the longest time, but with a lot of additions of people coming in and a lot of trade contacts with the larger Sahel, and that the Dogon were always traveling to other places.

I think it’s a much more dynamic scene, where people are moving back and forth. There’s cultural contact that should be seen in the material culture. So often the histories that are recorded in the oral traditions are about kings and conquests and all those sorts of things, but the lives of everyday people kind of go on and are expressed in the little broken pieces of pottery that archaeologists deal with.

###

Music:

“Daande Lenol”

Performed by Baaba Maal

Courtesy of Island Records under license from Universal Music Enterprises

“Daande Lenol”

Words and Music by Baaba Maal

(c) Universal Songs of Polygram Int., Inc. on behalf of Universal/Island Music Ltd. (BMI)

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please complete and submit this form. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.