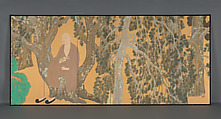

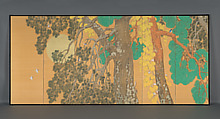

Tranquil Light (Jakkō)

Hashimoto Kansetsu 橋本関雪 Japanese

Not on view

In the serene natural setting of a cypress grove, a Buddhist monk sits cross-legged in meditation in the forking branches of an ancient tree. In his right hand he wields a vajra “thunderbolt,” a ritual implement symbolic of cleaving through ignorance; in his left hand he clasps a string of crystal Buddhist rosary beads. He has left his Chinese-style slippers at the base of the trunk. A squirrel is perched on branch on the far right. Opposite the monk, the sun glistens through another cypress tree, alongside a pine tree from which dangles a yellow-leafed vine, indicating the season is autumn. Another squirrel climbs the tree. Two small birds fly toward the grove; five others are perched in branches. The artist Hashimoto Kansetsu gave this set of six-panel folding screens the evocative title Tranquil Light (Jakkō 寂光). The term Jakkō is derived from the Buddhist term Jō-jakkōdo 常寂光土, or “Pure Land of Serenity,” which according to scriptures is a land “filled with the light of truth.”

The image of a monk meditating in a tree immediately calls to mind a famous painting of Monk Myōe Shonin (1173–1232), preserved at Kōzanji Temple. This image has multiple potential interpretations: it may refer to the historical Buddha Sakyamuni, who achieved enlightenment beneath a Bodhi tree; it may also reference images of Zen sages who typically encounter supplicants while seated beneath a craggy pine or other tree. Finally, it brings to mind images of arhats (disciples of Buddha) living in the wilderness, including one who is said to have meditated for so long that a tree grew up around him. It appears that Kansetsu transposed the image of Kūkai, the founder of Shingon sect of Esoteric Buddhism in Japan, into the setting of Myōe’s original portrait. But rather than suggesting a grove at Kōzanji Temple, the setting can be imagined to be Mount Kōya, where Kūkai established his headquarters after returning from China with the teachings of esoteric Buddhism. Surviving preparatory drawings by Kansetsu demonstrate that he considered various hand gestures for the figure of the monk before settling on the iconic pose of Kūkai. The imagery of Kūkai is no doubt derived from a version of the famous portrait in the set of Eight Patriarchs of the Shingon Sect. We can assume that Kansetsu was well aware of the legend that even after his death, Kūkai continued to dwell in eternity upon Mount Kōya.

Kansetsu was a renowned painter of Nihonga (Japanese-style paintings) who was active in the Kyoto art scene during the early twentieth century. Born in Kobe, he was the son of the painter Hashimoto Kaikan (1855–1935), from whom he acquired a deep familiarity with Chinese art and culture. He also studied modern Maruyama-Shijō school painting in Kyoto under the Nihonga painter Takeuchi Seihō (1864–1942), but eventually the two artists had a falling out over the direction Nihonga was taking in Japan. Kansetsu visited Europe in 1921 and 1927, which triggered his interest in Western-style painting. More importantly, beginning in 1913 and for the rest of his career, Kansetsu spent part of almost every year in China. Many of his paintings were inspired by scenery he experienced directly there, or were borrowed from Chinese legend and classical literature. Informed by Ming precedents, he brought a Nanga (Chinese literati) sensibility into his Nihonga painting. After his death, his former residence and extensive garden in Kyoto was converted into a museum called the Hakusasonsō 白沙村荘, which preserves a large collection of his works.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.