Front and three-quarter view of the shaffron. Shaffron (Horse's Head Defense), A.H. 1026/A.D. 1617–18. India. Steel; 23 7/8 x 8 in. (60.7 x 19.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Gift, 2008 (2008.197)

«The Department of Arms and Armor's current exhibition, Arms and Armor: Notable Acquisitions, 2003–2014 (through December 6), not only features notable European works, but also highlights superior non-Western ones. For example, there is a particular piece of armor associated with Indo-Islamic royalty. It was not made for an emperor, however, but for a horse.»

Since 1600 B.C., horses have been an integral part of Indian warfare and military campaigns, as well as immensely valuable and prized commodities. It is unsurprising, then, that defense armor for horses was widely used throughout the Indian subcontinent. This particular object is a fine example of a shaffron (kashka) or head armor, protecting the front of the horse's head from the ears down to the muzzle.

Made of a single piece of steel, this shaffron features a medial ridge ending in a drop-shaped, stepped, and raised panel in the center of the brow, and edges with a double-raised ridge and pins. It would have also had two separate ear-guards (now missing), which attached to the small curves at the top on each side. In addition, it would have had quilted or padded lining for comfort and to prevent the armor from slipping (Paul 124–5).

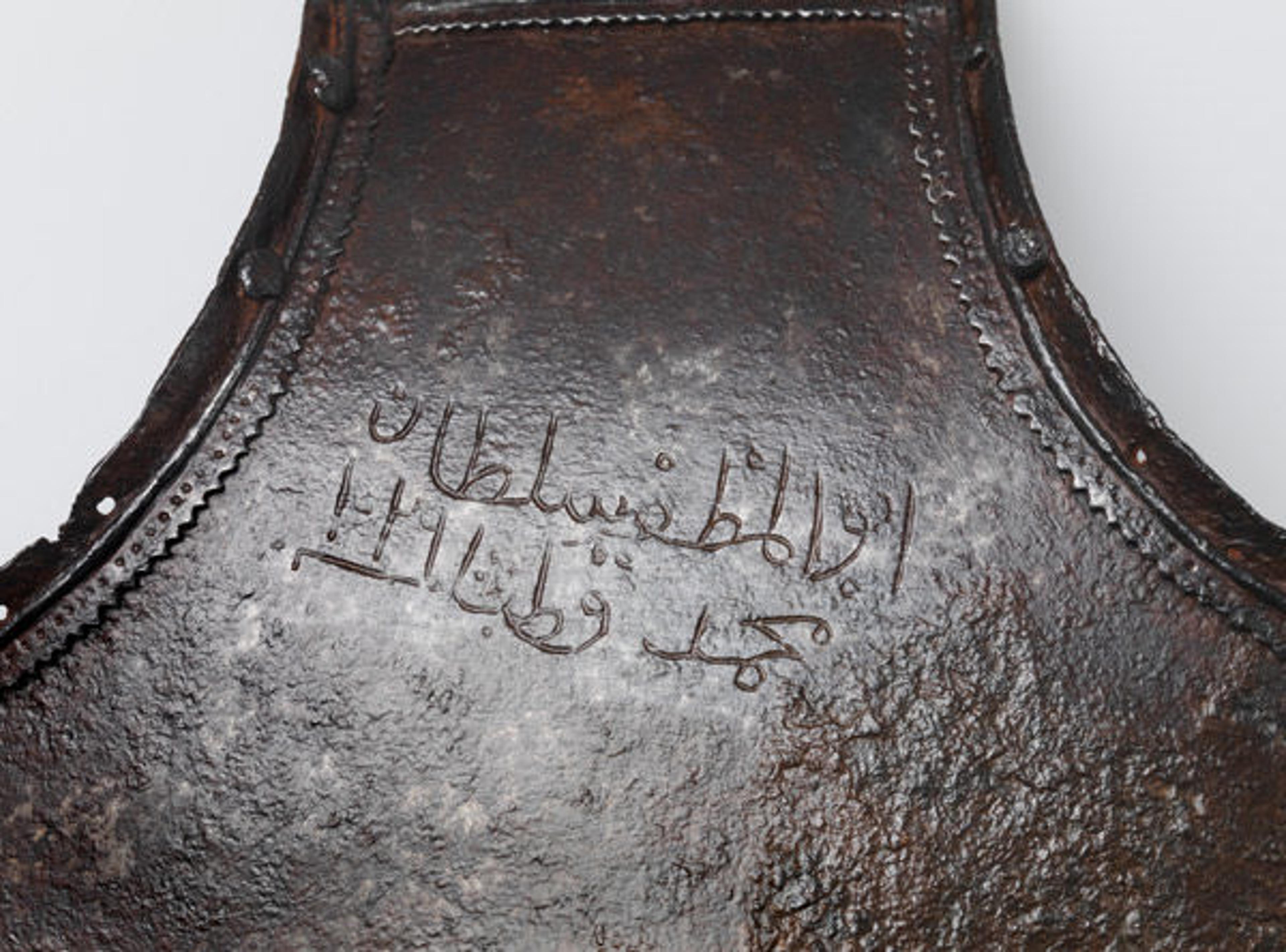

The overall design and style of this shaffron is characteristic of those produced under the Mughal Empire (1526–1857). The empire's cultural and artistic influence spread across India through trade, diplomatic affairs, military campaigns, and especially conquest. Thus, examples of this type of shaffron can be found from Rajasthan in the north, to the Deccan plateau in the south. Despite the shaffron's simple design, it is a rare example, and one that also imparts essential information about its historical provenance. An inscription, in Arabic, near the top edge of the shaffron provides a name and a date. It states, "Abu al-Muzaffar Sultan Muhammad Qutb, sanat 1026." The year (sanat), 1026, is from the Muslim or al-Hijri calendar (A.H.) and converts to 1617. The name refers not to the artist, but rather the sixth emperor of the Qutb Shahi Dynasty (1518–1657), Sultan Muhammad Qutb Shah, who reigned from 1611 to 1625. ("Sultan" is part of his name, not his imperial title.) The inscription, therefore, places the shaffron in the middle of Sultan Muhammad Qutb Shah's reign.

The inscription on the shaffron, which reads: "Abu al-Muzaffar Sultan Muhammad Qutb, sanat 1026." Shaffron (Horse's Head Defense) (detail), A.H. 1026/A.D. 1617–18. India. Steel; 23 7/8 x 8 in. (60.7 x 19.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Gift, 2008 (2008.197)

Sultan Muhammad Qutb Shah of Golconda, 1605–1625. India. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper. The Victoria and Albert Museum, London (IM.22–1925) © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The Qutb Shahis Dynasty, which ruled over Golconda in south India, and was one of the five empires that comprised the Deccan Sultanate. The dynasty was founded by Turkoman Sultan Quli Qutb-ul-Mulk (r. 1518–1543). In the beginning of the sixteenth century, he migrated to Delhi from Hamadan, Iran. Later, he moved to the Deccan to serve Mohammad Shah, sultan of the Bahmani Empire (1347–1527), the first independent Islamic kingdom of South India. After the disintegration of the Bahmani Empire, he conquered Golconda, took the title of "Qutb Shah" (divine or saintly king) and established the Qutb Shahi Kingdom.

This shaffron could have been personally made for and used by the sixth emperor, or, at the very least, it could have been utilized during his service. Although the Qutb Shahi Sultanate greatly patronized Persian culture and language, due in part to their emulation of the Safavid Dynasty (1501–1736), Arabic was used for official inscriptions such as titles and dates, honorific titles, and Qur'anic verses. Thus, the use of Arabic on this armor only augments its associations with royalty.

Sultan Muhammad Qutb Shah had a relatively short reign that was historically overshadowed by his predecessor, Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, who was also his uncle and father-in-law. However, what is known of the sixth emperor is that he had a great passion for books and made significant contributions to the royal library, including the first written history of the Qutb Shahi Dynasty (Welch 318).

This Indian horse armor is one of only a few surviving dated examples associated with a specific person. The fact that it is connected to a short-ruling, often-overlooked emperor makes it all the more extraordinary.

Sources

Paul, E. Jaiwant. Arms and Armor: Traditional Weapons of India. New Delhi: Roli Books, 2005.

Welch, Stuart Cary. India: Art and Culture, 1300–1900. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985.