Sonic Storytelling with 3-D Audio at The Met

Sound captured in the two microphone "ears" of a binaural recording head mimics our experience of 3-D sound through our own ears. Photo by Nina Diamond

To produce The Met's first 3-D audio experience—an immersive tour integral to the current exhibition Visitors to Versailles (1682–1789)—my team and I entirely rethought the idea of a typical audio tour. Our goal? To bring alive the actual experiences of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century visitors to Versailles. To do so, we used binaural audio not just to record narration, but also to construct sonic landscapes that include sound effects and music, all aimed at engaging listeners' imaginations in an entirely new way. Many describe it as uncanny and surprising, as if they're walking the palace halls and exploring the gardens alongside those speaking.

Months of work with my team went into research and script development before I was ready to fly to London to meet Chris Timpson, a sound designer and cofounder of Aurelia Soundworks, The Met's production partner for this project. Since I'd written the script entirely from adaptations of the accounts of actual seventeenth- and eighteenth-century visitors, when it came time for casting, the biographical details really mattered. How old were all the historic visitors? Where were they from? What kind of accents did they have? To which class were they members? Were they humorous? Stiff? Were they impressed by the palace and the court, or critical?

To align the pace of the audio experience with what would be visitors' physical movement through each gallery, Chris Timpson and I referenced the exhibition's floor plan to anticipate when and where Museum visitors would see various objects. Photo by Nina Diamond

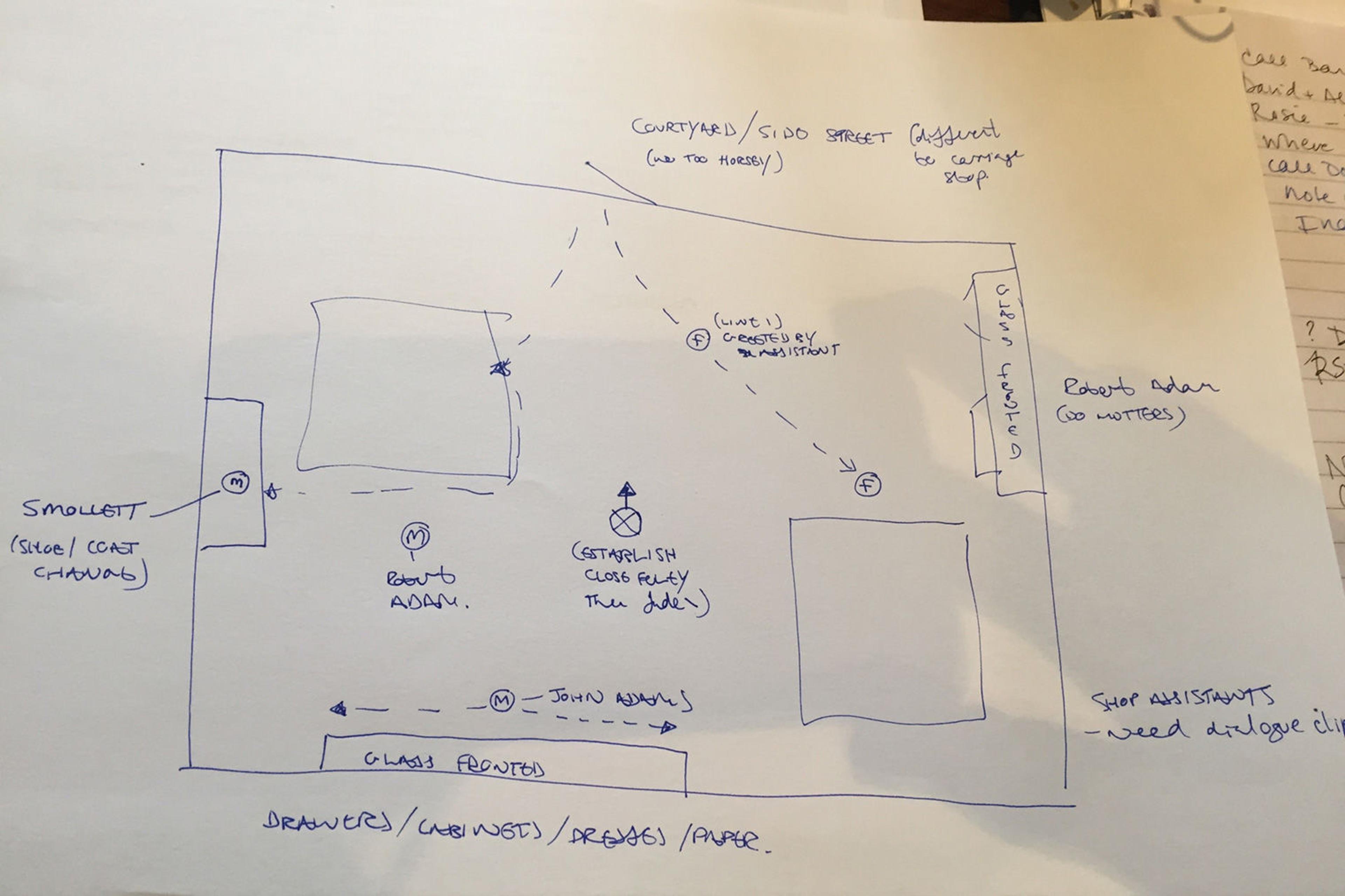

In sketches like this one for "Getting Dressed for Court," Chris Timpson and I mapped out how actors would need to move around the binaural recording head to take advantage of its dimensional capabilities. Photo by Nina Diamond

I'm grateful to have been able to work closely with voice-actor director Daniel Marcus Clark to review actors' audio and video samples provided by more than twenty UK agents. Daniel's experience, imagination, and sense of humor were invaluable as we selected more than a dozen actors hailing from the Isle of Wight, Germany, France, and elsewhere—all chosen for their ability to convincingly portray a specific historic visitor.

For example, we cast the remarkable Scottish actor David Mara to animate an account written by his fellow Scotsman, Tobias George Smollett, who described the elaborate costumes required to visit the palace in 1763. Listen to how beautifully Mara captures Smollett's combination of wonder and skepticism regarding France's passion for fashion.

Our project was often aided by serendipity. When we cast the American actor Mitchell Mullin to play John Adams, we didn't know that he'd already played the former president in several productions. Apparently we weren't the first to appreciate the integrity and gravitas his voice conveys.

In "Getting Dressed for Court," David Mara (left) performs excerpts of an account written by fellow Scotsman Tobias George Smollett. Smollett visited Versailles in 1763 and described the elaborate costumes required, with wry humor. Joseph Bone (right) reads from the writings of Robert Adam, a Scottish architect and designer. Photo by Daniel Marcus Clark

In "To See the King," Alison Skilbeck wittily portrays the British writer Madame Cradock, whose account of visiting the palace described . . . Oh! A sighting of the queen! The excitement caused Cradock's maid to faint, while she herself (supposedly) remained calm. Photo by Nina Diamond

But strong casting is only one way to achieve authenticity. We also had to ensure that the timing of the narration and sound effects in the final product would align with the design and physical layout of objects in the exhibition galleries. Because we planned to use a binaural recording head, it was that much more complicated to move from paper to production. The dummy head has two microphones, which record sound that, when played back on the proper headphones, mimics how our own two ears perceive the world around us: in 3-D.

Chris and I choreographed how the actors would need to move around the recording head when delivering their lines. For example, since the exhibition gallery "The Gardens" displays objects related to the fountains on the left, we'd need the sound effects of water to be on that side and for actors to direct their lines into the left ear of the binaural head.

The soundscape devoted to "The Gardens" gallery reflects research into the actual animals that were in the royal menagerie. At center: Fox Setting Fire to the Tree with the Eagle's Nest, 1673–74. French. Painted lead, 47 1/4 x 33 1/16 in. (120 x 84 cm). Musée National des Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon (MV 7946.1)

Days later, we were ready to record actors performing the script. Based on our choreography, Chris coached them how to move around the head, and how close to get to its two microphones. Daniel and I listened to each take and gave direction from the control desk.

I was taken aback by how suddenly the script came alive. I had previously worried, for example, that one particular section of the script might be dull: I'd adapted it from a long, formal eighteenth-century court report of the Siamese ambassador's entry into the Hall of Mirrors. But when performed by versatile actor Michael Mears, the grand moment has an emotional subtlety that conveys undercurrents of excitement in the assembled crowd.

Mitchell Mullins's performance in the gallery called "American Visitors, Growing Decline" captures a vulnerable moment for John Adams: the colonies desperately needed France's financial support, but he didn't speak French. Listen for Chris Timpson's addition of the sound effect of a ticking clock in the background of a small room, which underscores what must have been the awkward silence in that important moment.

Recording talented actors in a studio is fairly straightforward, but their performances alone would not evoke the unique interiors of Versailles. Rooms are characters too; they have specific aural footprints. For our audio to sound like the actual palace—with its high ceilings, chandeliers, mirrored walls, and parquet or marble floors—the crew and I went to southwest England for an unusual casting call.

Picture Devon, England, in the early twentieth century. Enter stage left: heir to the Singer sewing machine fortune, Paris Singer. Enter stage right: famous American dancer Isadora Duncan, with whom he was besotted. She, herself, was smitten by the grandeur of the palace of Versailles. In his efforts to woo her, Paris completed the construction of Oldway Mansion in Paignton, Devon, a country house begun by his grandfather in 1871, featuring rooms modeled on those at Versailles.

The exterior of Oldway Mansion in Paignton, Devon, England, as seen through snow thrown by the storm nicknamed the "Beast from the East." Photo by Nina Diamond

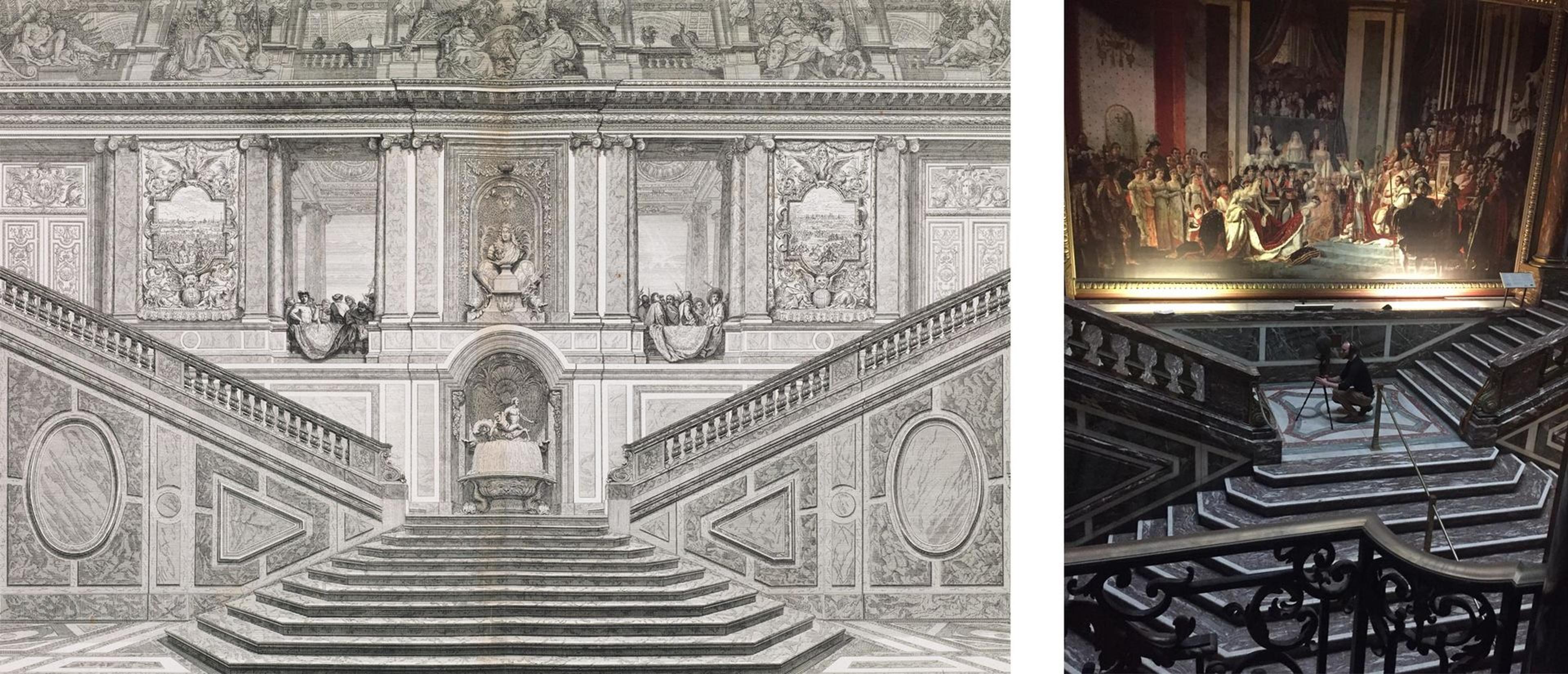

When we arrived at Oldway on a snowy March morning, my jaw dropped at the proportions of the interiors and their architectural detail, including a colossal double marble staircase. Here was the sonic environment we needed to record in to convincingly match that of the château. Though outside a storm was gathering into what would soon be dubbed the "Beast from the East," we hurried to record key actors within the mansion's remarkable rooms.

For example, to capture sound that suggested movement through the palace's diverse architectural spaces, we recorded the spirited actor Joe Bone as he charged up Oldway's replica of the marble Ambassadors' Staircase, through a corridor, and up some old wooden stairs. Chris scurried behind him in socks (so as not to make a sound), carrying the recording head.

The result? When you listen to the scene "Off-Limits," in which writer Henry Swinburne visits the private apartment of the king's opera-obsessed mistress, you'll sense that you are rushing through the palace alongside him, too. When Swinburne then mounts a small, winding staircase, you'll also hear the wood creaking underfoot. As you climb together, the delicate voice of actor and singer Karoline Gable spills from an open transom of a doorway at the top. When it opens, you hear her resume singing the aria, but this time it's as if you're inside the room, too. To achieve this effect, the team recorded Gable singing the aria two different ways: first from outside, on the staircase; then inside a low-ceilinged room that evokes the salon of Madame du Barry.

While the storm whips up outside, the crew enjoys front-row seats to Karoline Gable's (left) performance of "Lascia ch'io painga," an aria from George Frideric Handel's opera Rinaldo (1711). Photo by Rebecca Heal

Chris also added digital effects in postproduction to further enhance the sense of moving through the palace and being in the private apartments. If you listen closely, halfway through the aria the wind seems to pick up outside and there's a kind of dimensional shift in Gable's voice. These details evoke the feeling that you and the others in the salon have entered a wistful reverie. When this transporting sound effect evaporates, it's as if you're back in the salon again, with the crowd applauding around you.

Things don't always sound the way one expects when recording audio material. This means, somewhat ironically, that to make things sound real, we used a variety of approaches and tricks to simulate a certain result. Take the recreation, for example, of being in an eighteenth-century crowd. For this, Chris and Daniel used a recording technique conceived by Walter Murch, a famous picture editor and sound designer: "worldizing" allows editors to play back existing recordings in a specific space (in this case at Oldway), and then to re-record that material blended with the room's own sound.

Our production features sound captured through a variety of different binaural recording methods, including worldizing. Here, in Oldway's Hall of Mirrors, worldizing resulted in a sense of moving in and out of conversations in a crowd that features in the "Overseas Embassies" soundscape. This is the result of how close the binaural head was to a given loudspeaker. Photo by Daniel Marcus Clark

To do this, the team brought recordings of some of the performances we'd captured in the London studio into a sound installation set up in Oldway's Hall of Mirrors. From twelve loudspeakers set around the space, these performances were played back to mimic the noise of an actual crowd. By walking the binaural head past the loudspeakers in a choreographed course (that is, among our virtual crowd)—sometimes closely, sometimes far away—they place those speaking in a convincing, evolving aural landscape. When you listen, you'll hear a rich combined sound that gives the sense that you, too, are moving through the room, in and out of conversations.

Postproduction allowed Chris the opportunity to work sound-design magic in myriad ways. By layering as many as thirty to forty separate tracks of sound in each scene, he gave the soundscapes a sometimes startling immediacy. For example, when I heard an early version of one scene, I found the sound effects unconvincing. When the queen was approaching with her entourage in a froth of silk dresses, could he make it sound more lush and feminine? Chris solved this not by recording the sounds of elaborate costumes, but instead with a process commonly employed by foley artists: recording everyday or unrelated items, and then blending them together to create a new sound that has the desired qualities.

In this case, Chris recorded a flapping pair of gloves, swishing bedsheets and blankets, and even a rustling Hawaiian lei. After experimenting with the sound layers, he found that mixing multiple tracks of recorded footfalls, slightly offset from one another and further layered with the sound of rustling fabrics and jewelry, provided the right sense of structure to accurately convey a small posse of elegant women roaming the palace.

The Ambassadors' Staircase no longer exists at Versailles, but it lives on at Oldway. We remain indebted to the local Torbay Council, which now owns the estate. At right, Chris Timpson sets up the binaural head on the landing of Oldway's Hall of Mirrors. Photo by Nina Diamond. Left: "View of the Ambassadors' Staircase" (detail), plate 6 from Le Grand Escalier du Château du Versailles (Paris: Louis Surugue, 1725). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1918, transferred from the Library (1911.1073.55)

By this time, the Beast from the East had put the Devon community, if not the country, on red alert. The mansion guards urged us to make a hasty exit into the fierce wind and snow. The crew and I inched along icy roads, past grim pile-ups of cars, and were finally forced to abandon our vehicles and walk the last stretches back to our homes or hotels where we were stranded for several days. It was the worst storm to hit Devon in eleven years.

Once I returned to New York, grateful and tired, my team and I spent weeks reviewing the rough cuts, suggesting edits and working together to add depth and refine each soundscape. This included attention to even the smallest details, such as adding the cry of a peacock in the background of the garden, a grumble in French about the weather, and a quiet yawn at the end of the party scene.

With the exhibition now open, I'm very grateful to the teams in both countries who enabled this project to come full circle. Visitors may now experience these unique soundscapes both in the galleries and online. Sonic storytelling has allowed us to extend what is a brand-new invitation to Museum visitors. Come visit Versailles: you and your imagination won't believe your ears.

Related Content

Visitors to Versailles (1682–1789) is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through July 29, 2018.

Learn more about the binaural audio experience and view the exhibition galleries.

Read a blog series about Visitors to Versailles on Now at The Met.

The exhibition catalogue is available for purchase at The Met Store.

Nina Diamond

Nina Diamond is an executive producer and editorial manager in the Digital Department.