Richard E. Stone, Conservator Emeritus (February 2, 1939–November 15, 2021)

Our longtime colleague, Richard Edward Stone, passed away on November 15, 2021. Dick, as he was nearly universally known, was born and raised in Brooklyn. He majored in chemistry at Brooklyn Technical High School and often spoke of an introductory class in metal casting as the spark that ignited his lifelong interest in technology. While studying art history at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, Dick worked during the summer months as field conservator for the Harvard-Cornell Archaeological Exploration of Sardis (Turkey). There he continued to forge an ever-expanding vault of knowledge rooted in ancient history and technology that grew to cover virtually everything. Dick’s groundbreaking interpretation of the pyrotechnic processes evidenced by finds at Sardis established the city, ruled by King Croesus, legendary for his great wealth, as the earliest ancient center of gold refining.

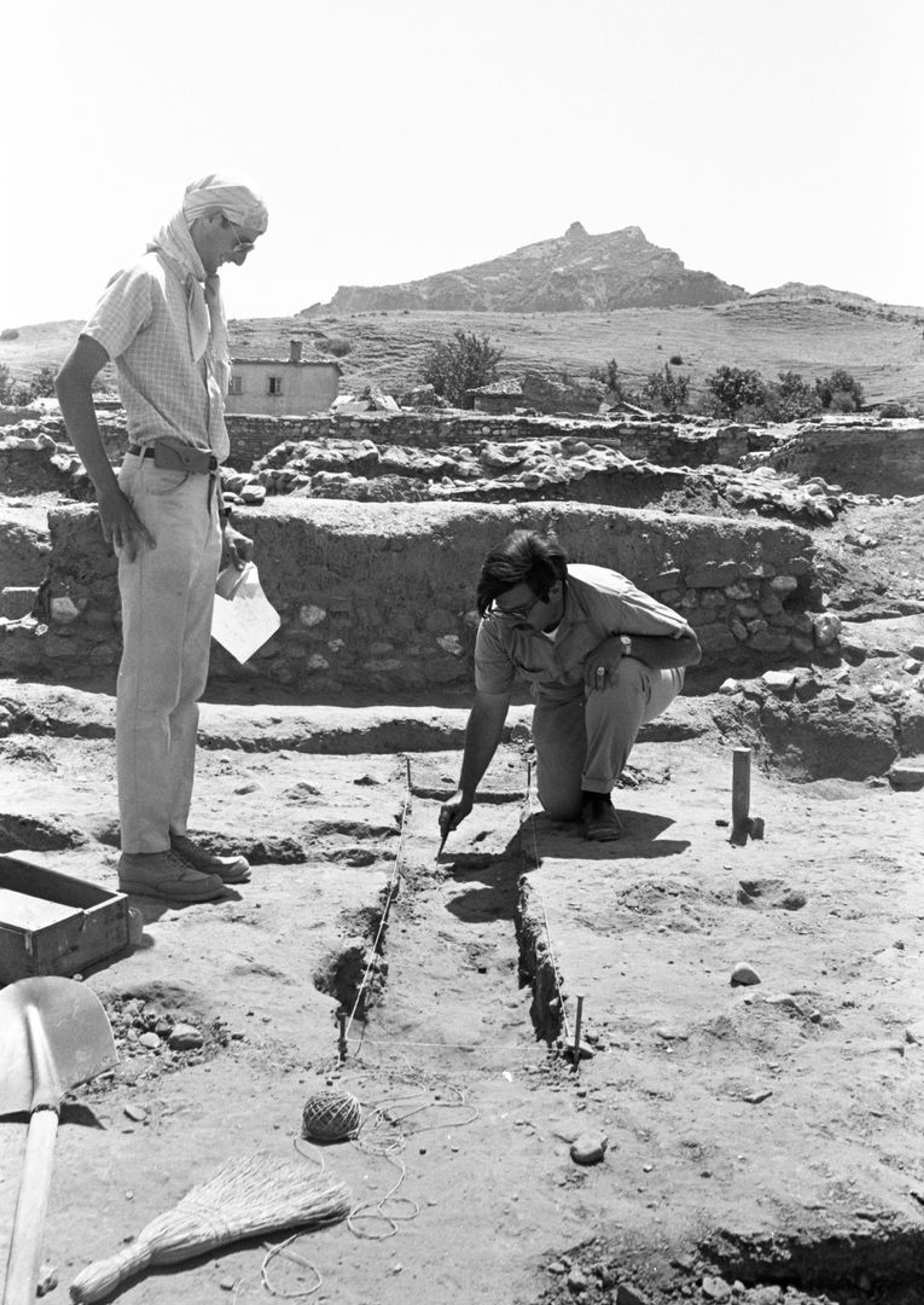

Crawford Greenwalt III and Dick Stone examining an archaeological feature at Sardis

Dick taught undergraduate art history for several years before joining James H. (Tony) Frantz in the Department of Objects Conservation at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1978. Together they helped build one of the most technically advanced, well-equipped, and well-staffed conservation labs in the world. The value that they placed on the crucial relationships between curators, conservators, and conservation scientists continues to inspire members of the staff today.

Dick specialized in the technical examination of works of art in metal, mostly relating to questions of origin, construction, and authenticity, and was equally conversant in matters relating to all materials, ranging from ancient gold to medieval glass to modern plastics. He also provided general oversight of departmental investigations of three-dimensional works of art proposed for purchase by the Museum. His colleagues have described his contributions at acquisition meetings as tidal waves of information flowing down the long boardroom table, cresting over the heads of the Trustees and senior staff, temporarily stunning them with the depth and breadth of his expertise.

He was a voracious reader, and unlike most of us, retained everything, earning him the reputation of being a walking encyclopedia. Colleagues liked to test him on this occasionally, and he never failed to come up with the Latin name for some obscure plant, a recipe for the perfect key lime pie, or a better explanation for the elusive dark matter of the universe. Dick was gregarious by nature and was perfectly happy to talk with anyone, about anything, anytime, always with characteristic humor and aplomb.An equally gifted scholar and teacher, Dick was known for the clarity with which he could explain even the most complex concepts. He also believed that there was no value in dumbing things down. Once asked by a colleague if they should simplify the technical details of a presentation to the public, he quipped that it was better to leave people a little confused than to insult their intelligence.

Dick was Adjunct Professor of Conservation at the Institute of Fine Arts’ Conservation Center, where for many years he taught graduate students of art history on the materials and physical methods of artistic creation. His course was described by many of his students as a transformative moment in their academic and professional lives.

His publications on Renaissance patinas and the use of X-radiography to study bronzes accelerated scholarship in the fields of conservation and Renaissance studies by decades and they remain valuable resources to this day. His exposé of the Fonthill Ewer, a notorious nineteenth century forgery in the style of the Renaissance, published in the Metropolitan Museum Journal, is exemplary for its methodology and attention to detail; the vessel was just one among scores of ingenious fakes and forgeries he unmasked in the course of his career.

A brilliant editor, Dick was always ready to interrupt his own writing to support the many friends and colleagues who sent him drafts of their work. The generosity with which he shared his expertise with students, scholars, and collectors inspired a generation of professionals to focus on technical studies in their respective fields. A map situating all the people that Dick mentored over the years—many of whom are now in key curatorial and conservation leadership roles—would have colored pins fanning out across the world. He was a generous colleague on so many levels, providing emotional, pragmatic, and professional support to so many, both at the Museum and in the wider community.

Dick’s commitment to the Museum did not end with his retirement. After recently completing final edits on his technical introduction to the then forthcoming Catalogue of Italian Renaissance Bronzes, he told his beloved wife of many years, Elizabeth Rosen Stone, that he’d had a wonderful life and that he would love to return to the Museum to start it all over again.

We all will miss Dick for his scholarly achievements, encyclopedic knowledge, and wry sense of humor, and especially for his tender heart.