Within The Met’s deep holdings of historic valentines and other types of works on paper, flowers often appear not merely as decoration but as symbols laden with complex meaning. This essay explores some of these hidden gems and consider how flowers inspired creativity, carried secret messages, and allowed artists to celebrate love—not only on Valentine’s Day.

The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection contains a series of tobacco cards devoted to “Floral Beauties and Language of Flowers.” Each card combines a bust-length portrait of a young woman with a specific flower and its meaning. A carnation stands for pride, while the corn flower represents modesty. A poppy conveys consolation, while the tea rose signifies jealousy. The series consists of more than a hundred such cards, which form a visual dictionary to decipher any flower bouquet.

Issued by Duke Cigarette branch of the American Tobacco Company, Lithography by Donaldson Brothers, American. Carnation: Pride; Cornflower: Modesty; Poppy: Consolation; and Tea Rose: Jealousy, from the series Floral Beauties and Language of Flowers (N75) for Duke brand cigarettes, 1892. Commercial color lithograph, each sheet: 2 3/4 × 1 1/2 in. (7 × 3.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Gift of Jefferson R. Burdick (63.350.204.75.11, .15, .28, .45)

Released in the 1880s by the American Tobacco Company, the collectible card series is a commercial outcrop of a tradition that may be as old as mankind: the language of flowers, also known as floriography. In this means of visual communication, each flower or leaf holds specific meaning. One or several of these flowers could be used to construct a hidden message, legible only to those in the know.

Interest in floral symbolism soared in the nineteenth century when the production of valentines reached its zenith and coded floral tokens allowed for declarations of feelings which could not otherwise be freely expressed in Victorian society. Emotions such as love, honesty, passion, even mourning were represented by flowers, which became synonymous with their iconic meanings.

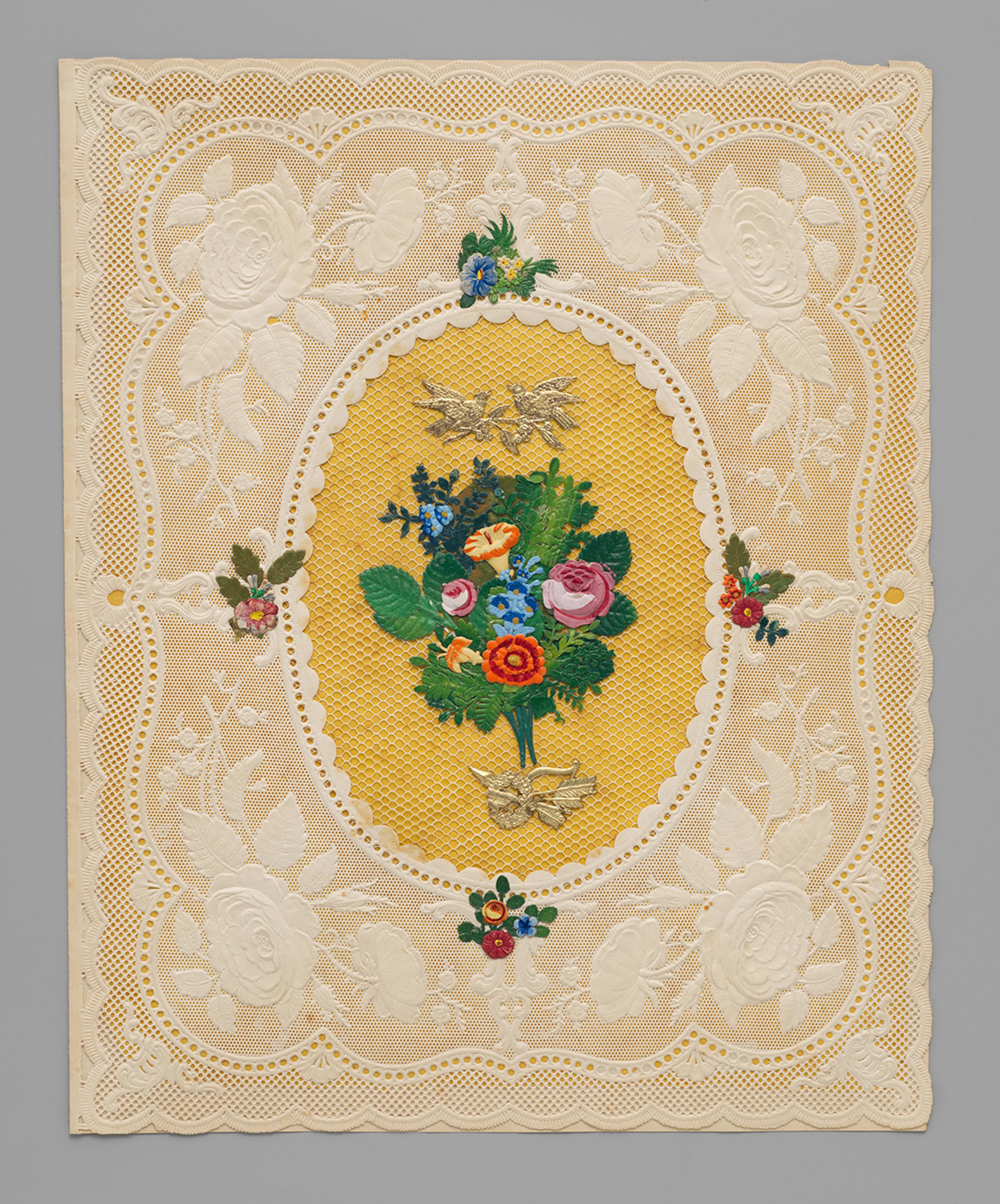

Attributed to Esther Howland (American, 1828–1904). Quarto Valentine, late 19th–early 20th century. Embossed paper with gilt “Dresden” paper doves, and hand-painted small clay molded flowers on silk with yellow tissue interleaving, Sheet: 7 7/8 × 9 7/8 in. (20 × 25 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1984 (1984.1164.1820)

This classic bouquet, attributed to Esther Howland (1828–1924), might be considered the ultimate valentine. By design, both the lace pattern and the embellished bouquet at center wordlessly convey its desired message. This fits the ethos of the iconic greeting card entrepreneur, who believed that personal sentiments should remain private, rather than being verbally emblazoned on the front for all to see. The beauty and simplicity of these embossed bouquets therefore carried their special messages quietly, but they could still speak volumes to recipients who were knowledgeable about the secret meanings hidden within the blossoms.

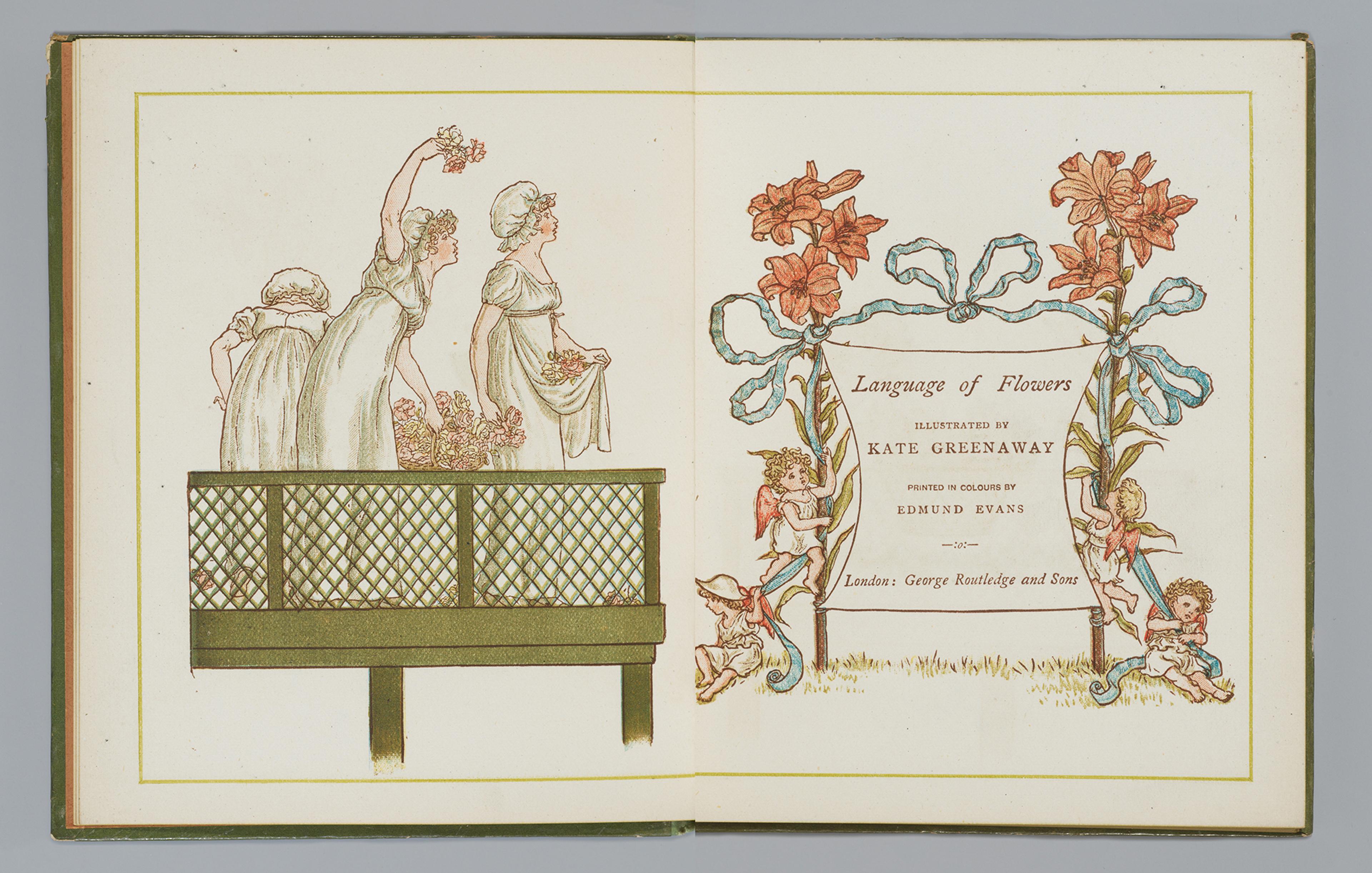

Kate Greenaway (British, 1846–1901). Published by George Routledge & Sons, London, British. Language of Flowers, 1884. Illustrations: color wood engraving, 6 x 5 in. (15.2 x 12.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. John Barry Ryan, transferred from the Library (1983.1223.5)

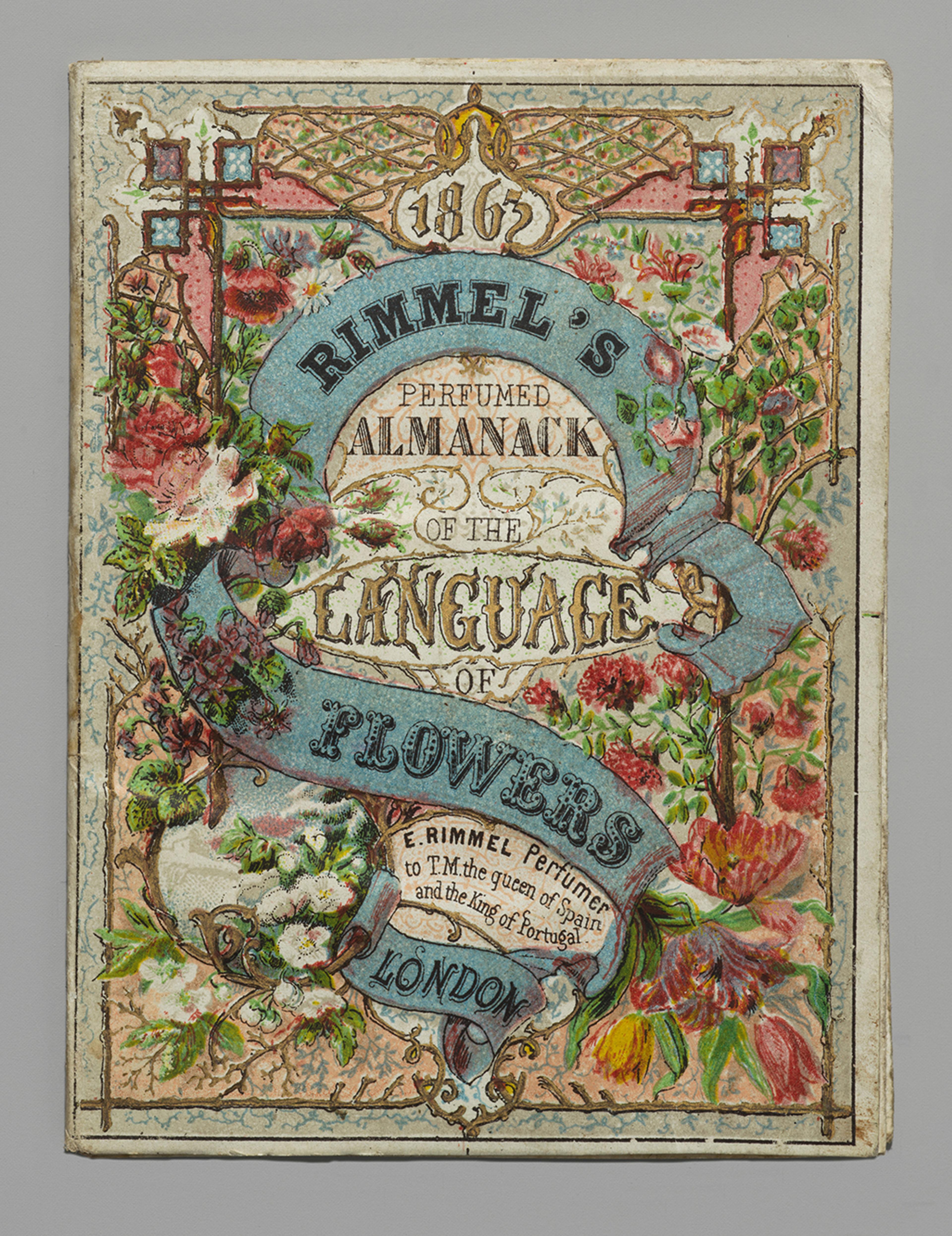

To acquaint people with this symbolic language and enable them to incorporate it into their valentines, the Victorian era also saw the introduction of popular guidebooks for floriography. They were available in various formats that catered to every stratum of society, such as the Language of Flowers (1884) by the popular writer and illustrator Kate Greenaway (1846–1901). Styled like an illustrated dictionary, each page is embellished with color wood engravings created by the color printer Edmund Evans (1826–1905). The famous London perfumer Eugene Rimmel (1820–1887), moreover, created luxurious scented almanacks to go alongside the extravagant hand-painted satin and lace perfumed valentines for which he was known.

Rimmel’s Perfumed Almanack of the Language of Flowers, 1863. Image courtesy of The Nancy and Henry Rosin Collection of Valentine, Friendship, and Devotional Ephemera

The connotations that were associated with each flower were derived from various sources, including religion, mythology, medicinal, or magical applications, as well as their own appearance. While symbolic meaning was applied to hundreds of flowers in this manner, none was ever as important as the rose. Its association with love evolved from sacred symbolism, as can be seen in a late seventeenth- or early eighteenth-century French devotional papercut, where the image of Mary Magdalene in the desert is surrounded by intricately cut roses representing divine love, purity, and the beauty of faith.

Devotional featuring Saint Mary Magdalene in the Desert, 18th century. French. Painted and gilt cut paper, Sheet: 7 7/8 × 8 1/4 in. (20 × 20.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1977 (1977.627.24)

Surviving Valentines attest to the omnipresence of flowers, which could be elegantly painted on substrates such as lace paper, rice paper, or satin. They could be steel- or wood engraved, lithographed or made by hand, sometimes further enhanced with magical mechanisms or a hint of perfume. The wordless bouquets or single flowers could form the central focus of the composition or quietly fill decorative borders with subliminal messages. Creative artists combined multiple flowers to add or adjust meaning: a rose, symbolic of love, might be paired with forget-me-nots, for instance. The addition of Cupid or the image of a wedding ring could transform a valentine from a loving gesture into a tender marriage proposal.

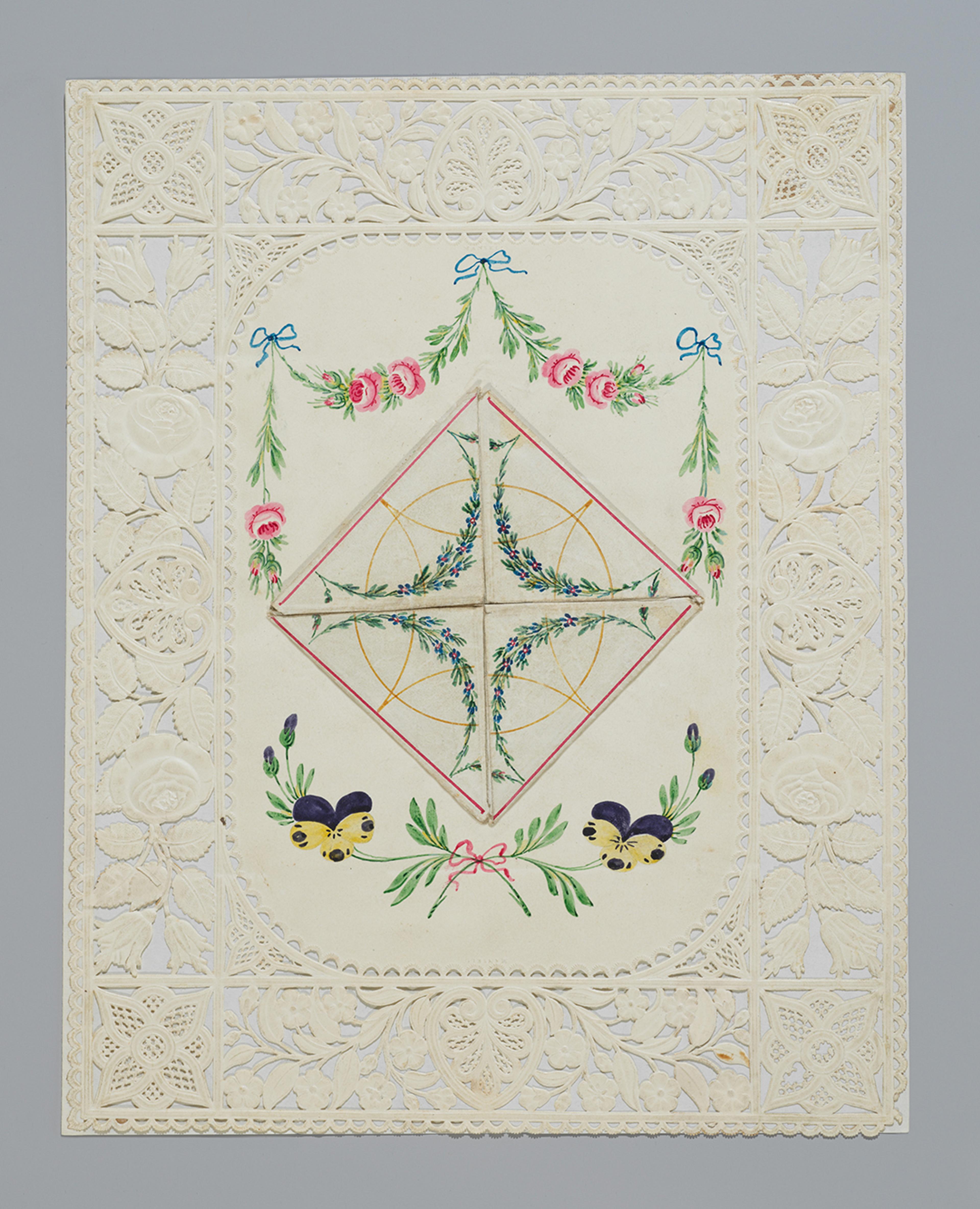

After Joseph Mansell (British). Quarto Valentine, ca. 1850. Watercolor, pen and brown ink on openwork cameo-embossed paper, Sheet: 7 7/8 × 9 3/4 in. (20 × 24.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1984 (1984.1164.1821)

Joseph Mansell (1803–1874), a commercial stationer in London, designed fine rag paper with luscious cameo-embossed border. Around 1840, one of those papers was used as the platform for this origami-like folded letter known as a puzzle purse. An initial viewing highlights delicately painted swags of roses (love) and pansies (thoughtfulness). While such a message could easily be exchanged among friends, or with a beloved family member, the card contains more than meets the eye. When the recipient unfolds the paper puzzle at center, the interior reveals a painted moss rose, signifying a confession of love, and beneath it, cutwork. As a cherry on the cake, a silk thread is attached that allows the moss rose to be lifted up in a network of concentric circles to reveal a final image of flying doves. This iconic interior mechanism is known as a Cobweb, Flower Cage, Beehive, Honeycomb, or Cupid's Web.

After Joseph Mansell (British). Quarto Valentine, ca. 1850. Watercolor, pen and brown ink on openwork cameo-embossed paper, Sheet: 7 7/8 × 9 3/4 in. (20 × 24.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1984 (1984.1164.1821)

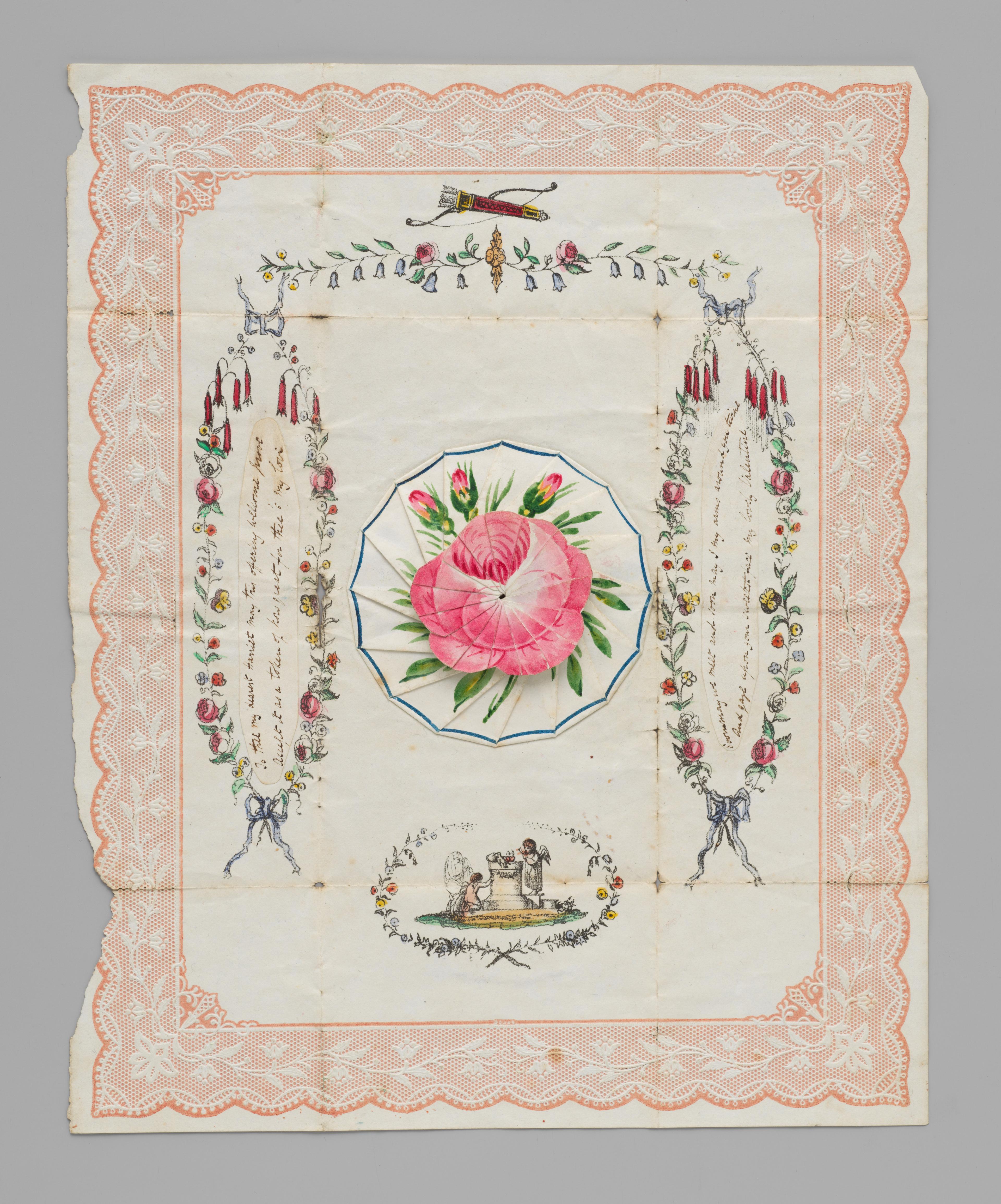

Dobbs, Bailey & Co. (British, active 19th century). Valentine with movable components, late 18th–early 19th century. Lithograph and watercolor, pen and brown ink on cameo-embossed paper, Sheet: 9 1/2 × 8 1/2 in. (24.1 × 21.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1984 (1984.1164.1822)

This valentine made by the firm Dobbs (active 1790–1815), is another example of the combination of a rose with movable components. Alongside the central rose, the initial view of the card shows delicately painted swags of roses (love) and a small but telling flaming altar of love below. The large paper rose is actually a rare form of puzzle. Its petals twist open to reveal another cobweb construction. This in turn hides an image of Cupid, a flaming heart, and the precious words “Love Enflamed.”

Dobbs, Bailey & Co. (British, active 19th century). Valentine with movable components, late 18th–early 19th century. Lithograph and watercolor, pen and brown ink on cameo-embossed paper, Sheet: 9 1/2 × 8 1/2 in. (24.1 × 21.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1984 (1984.1164.1822)

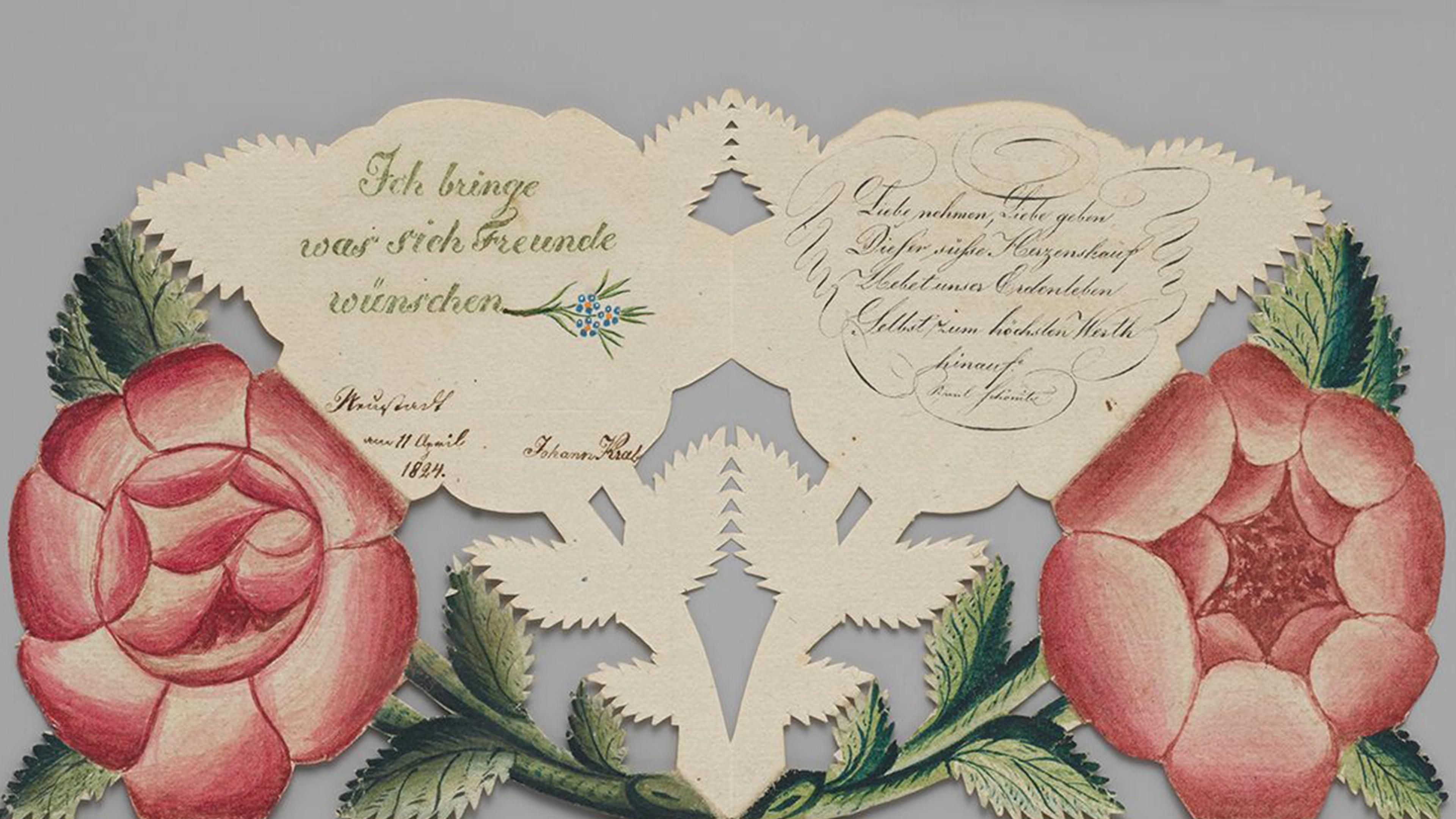

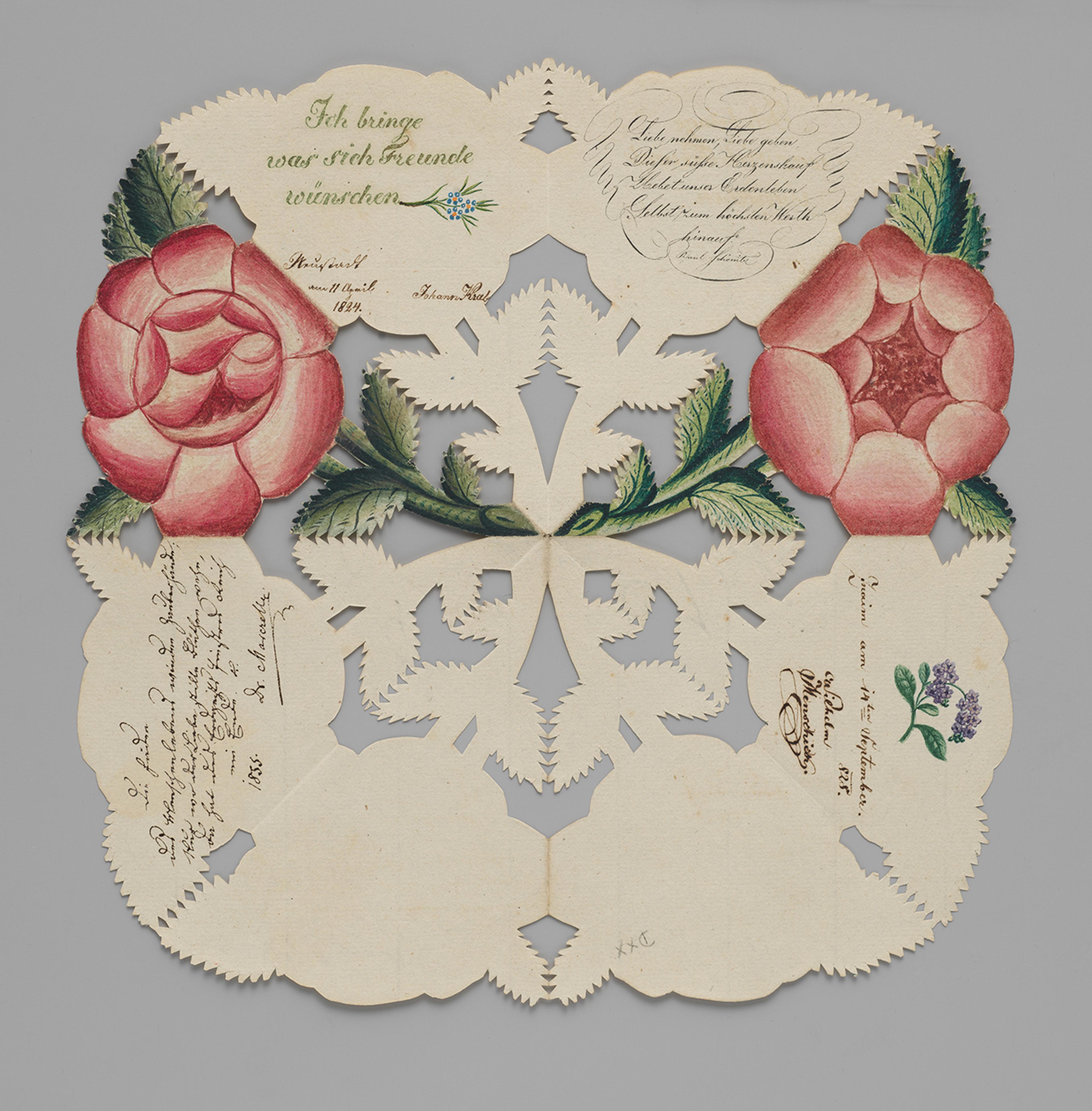

Attesting to friendship, rather than romantic love, is this papercut souvenir rose: an object related to the so-called album amicorum, or friendship album. When folded, the object takes the shape of a hand-painted rose, but when it unfolds blank spaces appear where family, friends, and acquaintances could leave their names and affectionate messages. This specimen is inscribed with well wishes in German, signed and dated in the years 1824, 1828, and 1855.

Greeting card with roses, ca. 1824. German. Cut paper, 8 1/4 × 8 1/8 in. (20.8 × 20.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1984 (1984.1164.13)

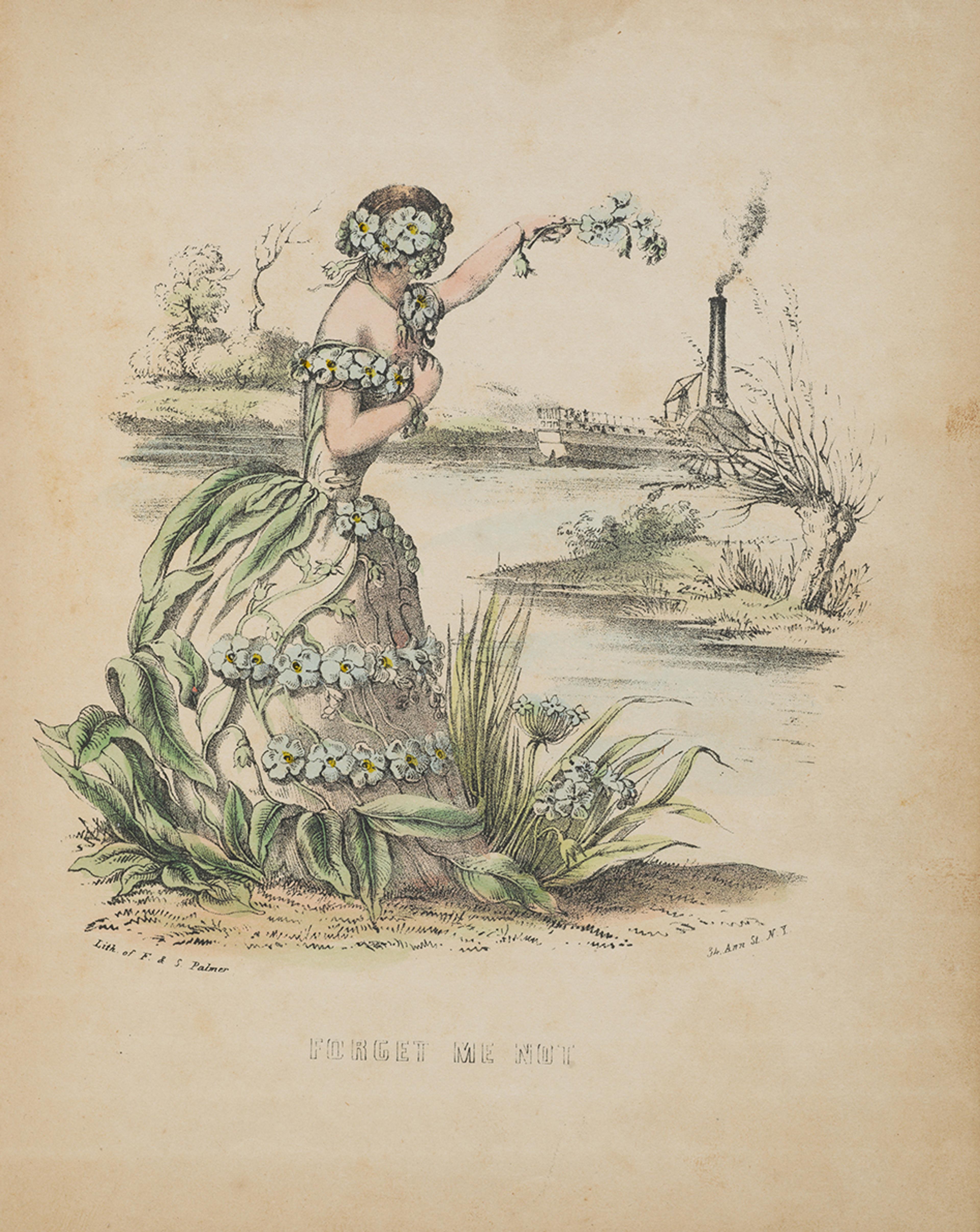

A charming album that follows this trend of interacting with a prefabricated object was published in New York in the 1840s. Called Flower Tokens, it takes the form of a small red leather binding with gilt-edged pages and contains illustrations by Frances (Fanny) Flora Bond Palmer (1812–1826), who became famous working for the print entrepreneurs Currier and Ives. Her illustrations in Flower Tokens consist of lithographed, hand-colored images of women as various types of flowers. They are interspersed with blank pages that offer room for personal compositions. The flowers provide tender incentive for lines about subjects such as purity (the orange flower), industry (flax), modesty (violet), farewells (forget-me-not), youthful hope (snowdrop), and repose (the convolvulus, or morning glory).

Frances Flora Bond Palmer (American [born England], 1812–1876). Forget Me Not, from Flower Tokens, 1847–49. Hand‑colored lithograph, 7 3/4 x 6 1/4 in. (19.7 x 15.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Lincoln Kirstein, 1970 (1970.565.190)

This particular copy was presented to a Maria B. Cooper of Newark, New Jersey. She claimed ownership of the booklet by writing her name in bold calligraphy, fittingly accompanied by a graphite drawing of a rose and pansy, which signify love and thoughtfulness. In addition, she filled forty-three of the blank pages with her poetry, while a loving friend penned down an acrostic for Maria.

Beyond valentines, many artists turned to flower imagery as important iconographic components of their work. In fact, centuries of floral-inspired art can be found throughout The Met's collection. Think, for example of the delicate bejeweled 19th-century Imperial Lilies-of-the-Valley Basket (symbolic of domestic happiness and conjugal bliss) by the House of Carl Fabergé, or the rich and colorful painted flower bouquet of the Flemish artist Clara Peeters, (ca. 1587–after 1636). As you visit the Museum next, I encourage you to be on the lookout for these subliminal floral messages and try to interpret their special meaning.