In 2022, The Met offered for the first time a fellowship designed to bridge the worlds of curatorial practice, and the scientific study of art. The 24-month Diamonstein-Spielvogel Fellowship allows a fellow to work collaboratively between the Departments of Drawings and Prints, Paper Conservation, and Scientific Research. This fellow is fully integrated into the three departments, with access to mentorship and resources in each.

As the Met’s first 24-month Diamonstein-Spielvogel Fellow, I have the opportunity to pose art historical questions, rooted in the collection, and to answer those questions using both traditional curatorial methods and The Met’s world-class resources in cultural heritage science. My fellowship research supports my dissertation, which considers the aesthetics and materials of seventeenth-century Netherlandish drawings and prints depicting iridescence in insects. Put simply: I study old pictures of shiny bugs. At the core of my project is an interest in how scientists both in the early modern period and today use images to produce and communicate knowledge. This fellowship allows me to explore both those perspectives on looking, learning, and image making.

I began my fellowship by familiarizing myself with the natural history drawings in the collection. I pulled interesting drawings out of their boxes and looked at each one. This kind of looking is fundamental to my training as an art historian. It requires analyzing composition, form, and handling of materials then comparing these aspects to other artworks to get a sense of how each work is significant in its broader context. I followed up my observations with background research and identified a select few objects to focus on for the remainder of my fellowship. For each object I proposed a set of art historical questions. For some I wondered about connoisseurship: who made the drawings? For others I thought about function: why was the drawing made? In others I had questions about the artist’s process of observing specimens. In all cases I wanted to better understand the processes of making drawings: what materials the artist had chosen, why, and how had they been applied?

Looking at natural history drawings in the Drawings and Prints Department study room

An essential stage of formulating my research questions was looking at my selected artworks with experts on staff in all three of the departments I work with. I looked at my drawings with curators, paper conservators, and research scientists to understand what they saw when they looked at them. Each person brought their own perspective to the drawings, noticing different aspects, proposing hypotheses to address different research questions, and raising new questions that I hadn’t considered. I then began diagnostic research using resources available through the Paper Conservation department. I started by studying the first two drawings I was interested in under the microscope. I quickly learned that looking at objects under high magnification is a skill of its own. It took time and practice to understand how different pigments would appear under magnification and how to interpret the complex layering of these materials.

A watercolor of a blue beetle by an unknown seventeenth-century Dutch artist under the microscope (left) and the beetle’s horn and shell under magnification (right)

Next, I used the Paper Conservation Department’s multi-spectral photography system to capture images of my drawings illuminated by several different wavelengths of light. Because materials that may appear similar in visible light reflect and absorb light differently in other wavelengths, this technique can provide valuable information invisible to the un-aided human eye. Understanding the images produced by this equipment required learning yet another way to look. As I practiced taking and interpreting these photographs, differences between materials that otherwise looked identical became clear, underdrawings emerged, and tool marks and brush strokes appeared. This extra evidence revealed surprising aspects of the drawing, for example in the case of the drawing of the blue beetle above, areas where the artist had reworked the composition.

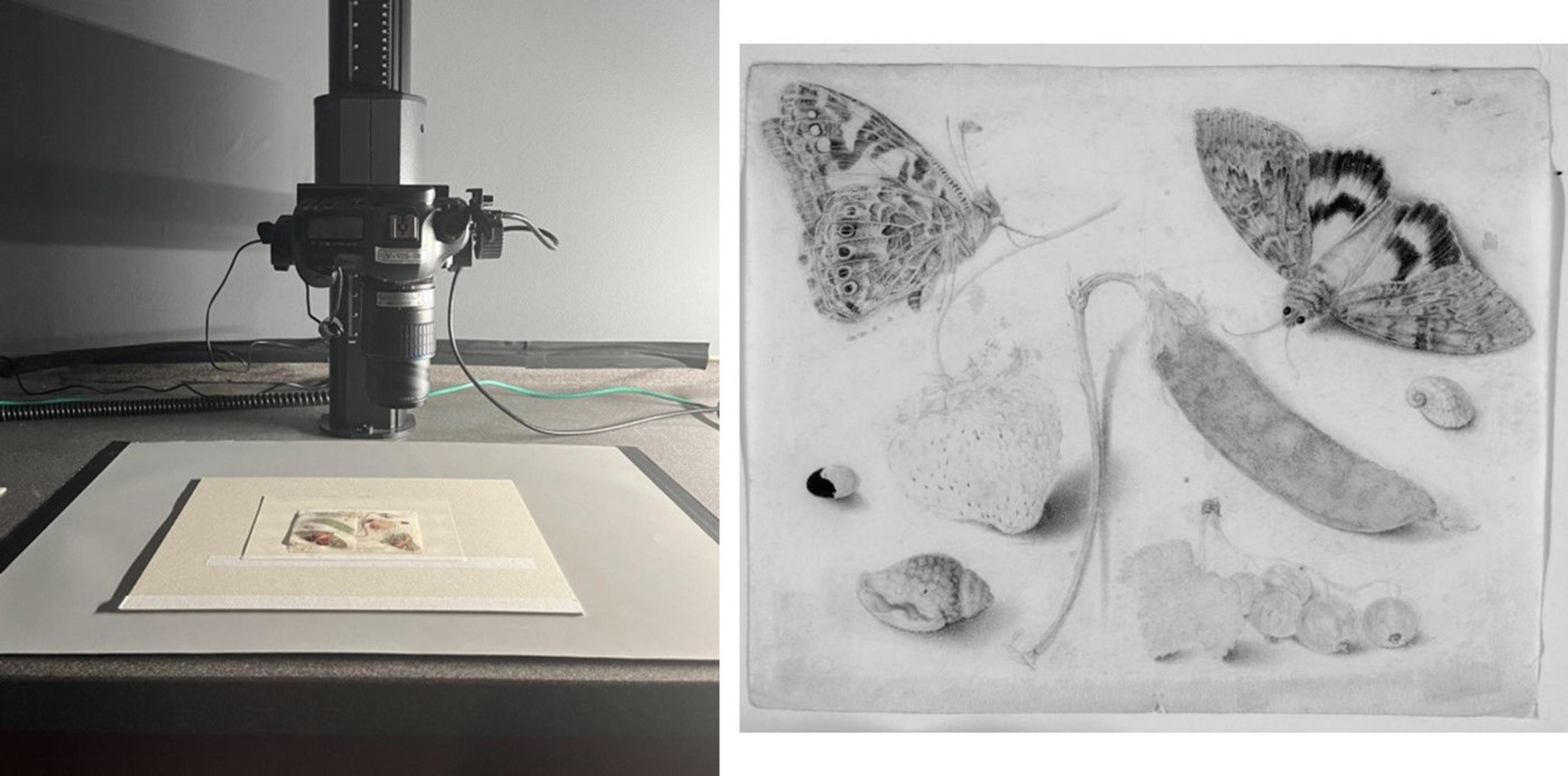

Drawing of fruits insects and shells by Georg Flegel, being photographed on the multispectral imaging station (left) and a resulting infrared image, used to assess underdrawings, and propose pigment identifications (right)

Working between what I observed under the microscope and the multispectral images, I came to an initial assessment of how these drawings are constructed. I am now taking my objects to the Department of Scientific Research to take advantage of instruments for non-invasive materials analysis. This stage of my research is ongoing, and I anticipate it will allow me to identify more specifically some of the materials I have encountered in my investigations in the Paper Conservation Department. As much as I have learned about the objects that I have been researching, I have also valued the opportunity to think about the overlaps between scientific inquiry and image making through the methods of paper conservation and to train my eyes to understand new kinds of images. Interpreting what I see through the eyepiece of a microscope or in a photo illuminated by ultraviolet or infrared light, making the visual connection between an anonymous drawing and works from a similar artist or time; all of these require different ways of looking that are practiced in the different spaces of the museum to which I have access through this unique fellowship opportunity.