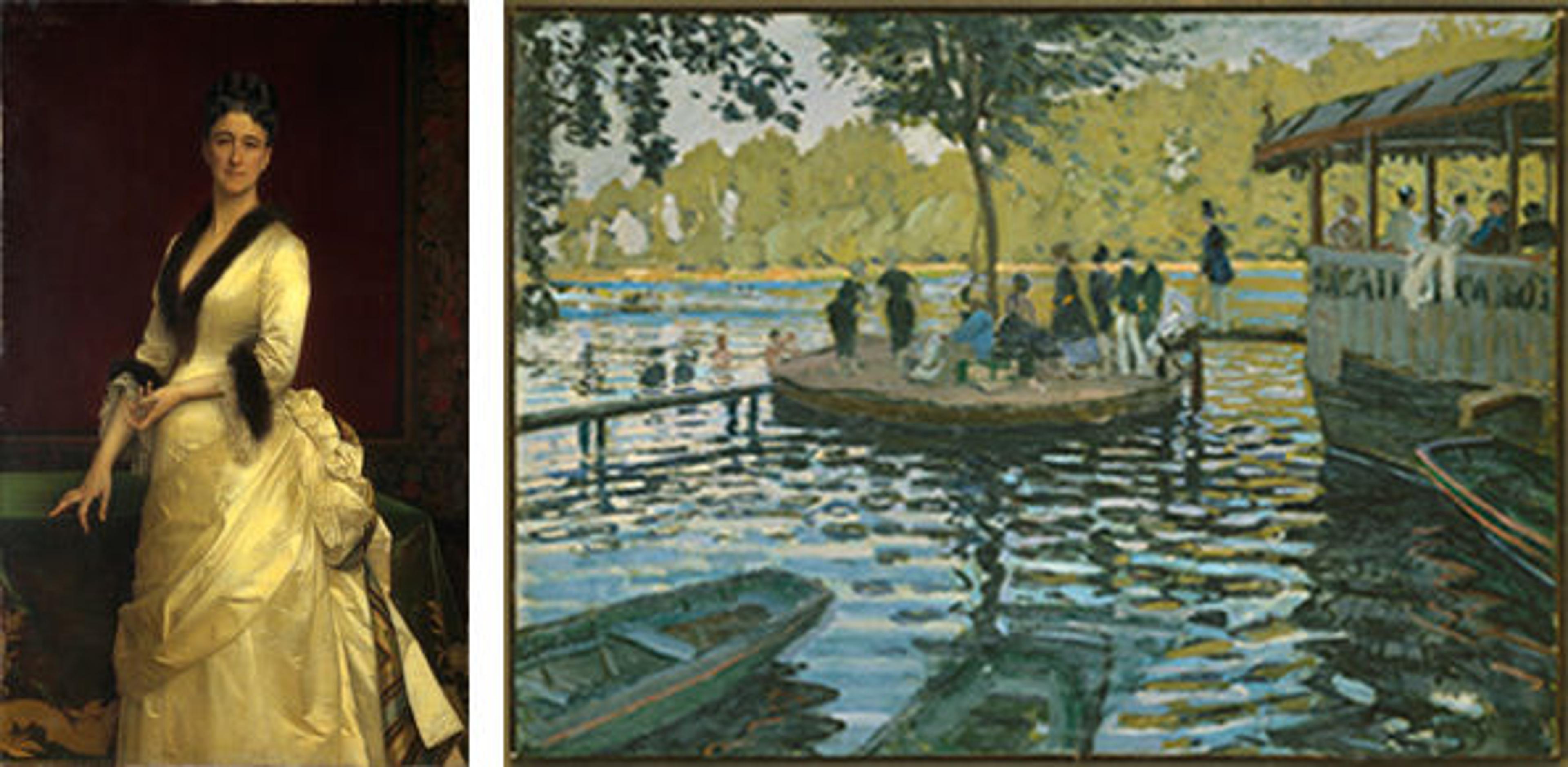

Left: Alexandre Cabanel (French, 1823–1889). Catharine Lorillard Wolfe (1828–1887), 1876. Oil on canvas; 67 1/2 x 42 3/4 in. (171.5 x 108.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Bequest of Catharine Lorillard Wolfe, 1887 (87.15.82). Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926). La Grenouillère, 1869. Oil on canvas; 29 3/8 x 39 1/4 in. (74.6 x 99.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929 (29.100.112)

«Okay, now don't get me wrong. While I'm sort of presenting the following ideas as fact, I don't claim to know much about painting or anything about Impressionism, but I am completely fascinated with the movement—actually head over heels infatuated. I want more than anything to understand how it works, so please forgive the following inelegant suppositions as the workings of a mind tussling with understanding.»

Impressionism is built upon evocation—bare and blisteringly simple—and yet it presents us with a complete sensory experience. Impressionist artists gently coax us into seeing a fully constructed world using only the faintest suggestions of light and color. An artist's ability to evoke reality like that means that he or she is intimately familiar with the world and knows it well enough to break it down into what makes it itself.

Well-executed evocation raises the issue of taste, or rather, judgment. Recently, on a tour through the galleries for nineteenth-century European paintings, the Teen Advisory Group encountered two distinct types of painting: the academic and the Impressionist. I sort of separate these two styles into the ideas of "skill" (academic) and "judgment" (Impressionism). Now I'm not knocking skill—it's fantastically impressive to look at something so realistically wrought, and I can't even imagine the amount of time and discipline it must have required to even learn to paint like that—but skill, in my opinion, is not particularly compelling. Because everything is there, everything is present on the canvas, the artist has to understand light, motion, and color but not judge. And that is where the real artistry lies: in what should go, what should stay, what makes the subject tick, and what can be removed while still leaving a whole.

Related Link

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: "Impressionism: Art and Modernity"