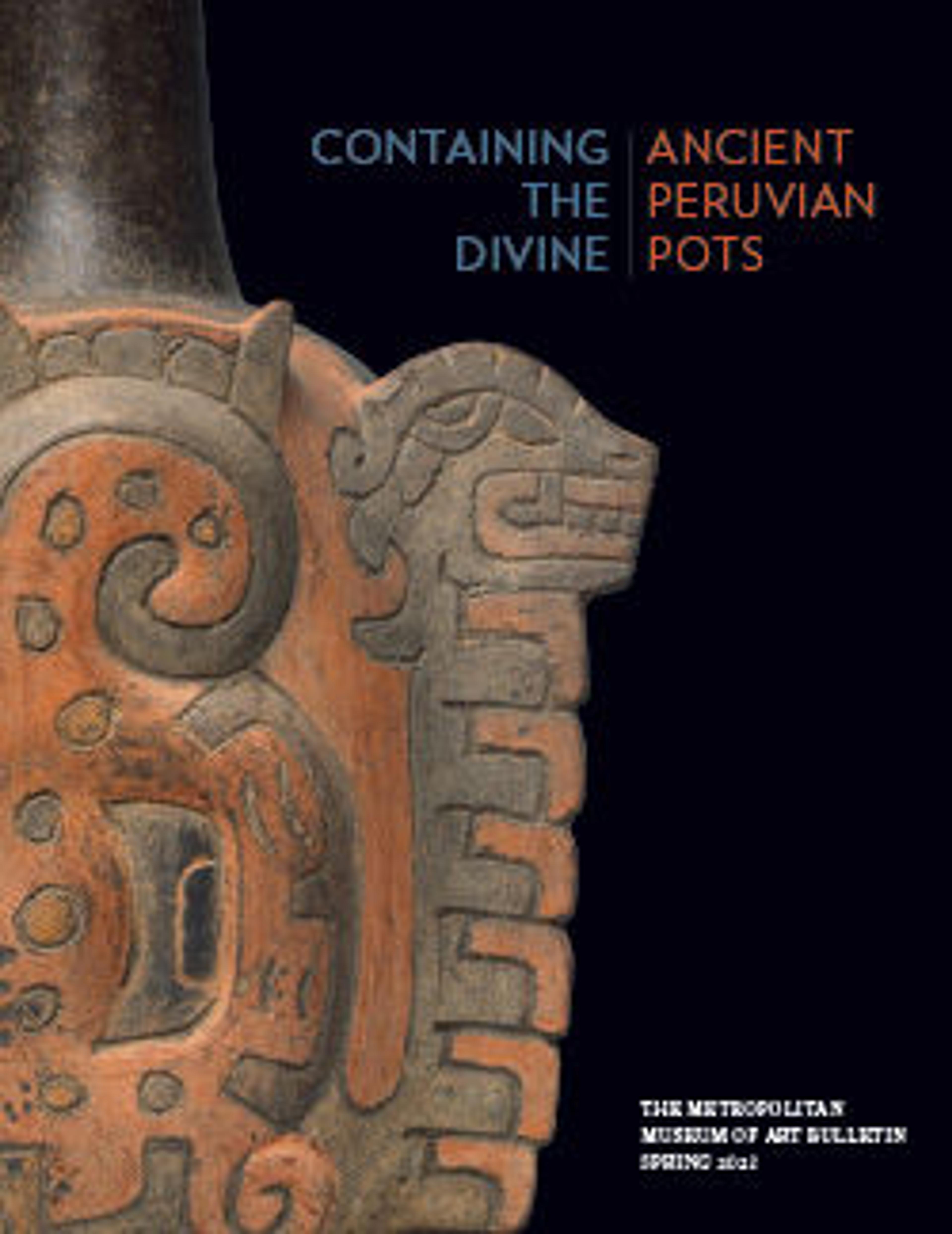

Stirrup-spout bottle

Cupisnique artists preferred a muted palette, usually the color of the fired clay itself, but they created visual interest by contrasting smooth and textured surfaces. On this stirrup-spout bottle, the unornamented sections were created by carefully smoothing the clay when leather-hard, and then burnishing it with a polishing stone (for an example of a polishing stone, see MMA accession number 1994.35.769). The textured areas were produced by adding appliqués and impressing a comb-like tool into the clay. The combination of smooth and textured areas is a visual and tactile reminder of the interior and exterior surfaces of Spondylus shells, a bivalve considered to be among the most precious ritual materials in the ancient Andes (see MMA 2003.169).

Hugo C. Ikehara-Tsukayama, Andrew W. Mellon Curatorial/Collection Specialist Fellow, Arts of the Ancient Americas, 2022

Further Reading

Burger, Richard L. Chavin and the Origins of Andean Civilization. London: Thames and Hudson, 1992, pp. 90-99.

Burtenshaw-Zumstein, Julia T. Cupisnique, Tembladera, Chongoyape, Chavín? A Typology of Ceramic Styles from Formative Period Northern Peru, 1800-200 BC. Unpublished PhD dissertation. Norwich: University of East Anglia, 2014.

Elera, Carlos. "El complejo cultural Cupisnique: Antecedentes y desarrollo de su Ideología religiosa." Senri Ethnological Studies, No. 37 (1993), pp. 229-57.

Artwork Details

- Title: Stirrup-spout bottle

- Artist: Cupisnique artist(s)

- Date: 800–500 BCE

- Geography: Peru, North Coast

- Culture: Cupisnique

- Medium: Ceramic

- Dimensions: H. 9 5/8 × W. 5 1/2 × D. 5 1/2 in. (24.4 × 14 × 14 cm)

- Classification: Ceramics-Containers

- Credit Line: The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1969

- Object Number: 1978.412.40

- Curatorial Department: The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Audio

1644. Botella de asa estribo, artista(s) cupisnique

Hugo Ikehara-Tsukayama

HUGO IKEHARA-TSUKAYAMA: En los Andes antiguos, la cerámica fue una clase de objeto que contenía mensajes e ideas. Contenedores cerámicos se convirtieron en soportes ideales para imágenes, mientras eran usados en rituales, o como objetos políticos que difundían ideas o mostraban autoridad y poder.

Mi nombre es Hugo Ikehara-Tsukayama, y soy investigador asociado senior para el arte de las antiguas Américas en el Metropolitan Museum of Art.

JOSÉ MARÍA YAZPIK (NARRADOR): Esta botella, elaborada hace unos 3000 años en la costa norte del Perú, tiene una característica asa en forma de estribo. La superficie de este recipiente muestra un contraste entre áreas pulidas y brillantes con aquellas con texturas rugosas parecidas al exterior espinoso de la concha de Spondylus, un molusco bivalvo marino.

HUGO IKEHARA-TSUKAYAMA: Las conchas de Spondylus fueron muy apreciadas por su vibrante color rojo y por ser vistas como una sustancia ritual ofrecida a los ancestros y otros seres divinizados.

En el siglo dieciséis, esta concha era considerada la comida predilecta de las deidades.

El Spondylus crece en las aguas cálidas de Ecuador hacia el norte. Por lo tanto, tener conchas de este molusco cuatrocientos o quinientos kilómetros al sur implica el movimiento de estos bienes entre diversas comunidades.

JOSÉ MARÍA YAZPIK: En los Andes, la gente traía grandes cantidades y variedades de vasijas a las celebraciones o festivales comunitarios, en ocasiones, con la participación de cientos de invitados.

HUGO IKEHARA-TSUKAYAMA: Quizás los organizadores de estas reuniones querían demostrar su habilidad como líderes… líderes que podían movilizar gente mediante sus redes sociales para conseguir diferentes clases de ollas, botellas, y cuencos de comunidades cercanas y lejanas.

Durante esta época debieron hacer esto cada vez que organizaban estas celebraciones.

JOSÉ MARÍA YAZPIK: Los arqueólogos han desenterrado conjuntos de cerámica destrozada, los restos de estas celebraciones. Al final de la reunión, los líderes destruían a manera de ceremonia las vasijas, como una muestra de su poder y autoridad, permitiendo y exigiendo nuevos ciclos de creación y ofrenda. La destrucción de estas obras de arte provocaba una demanda de nuevas vasijas y estimulaba una mayor invención e innovación artística.

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.