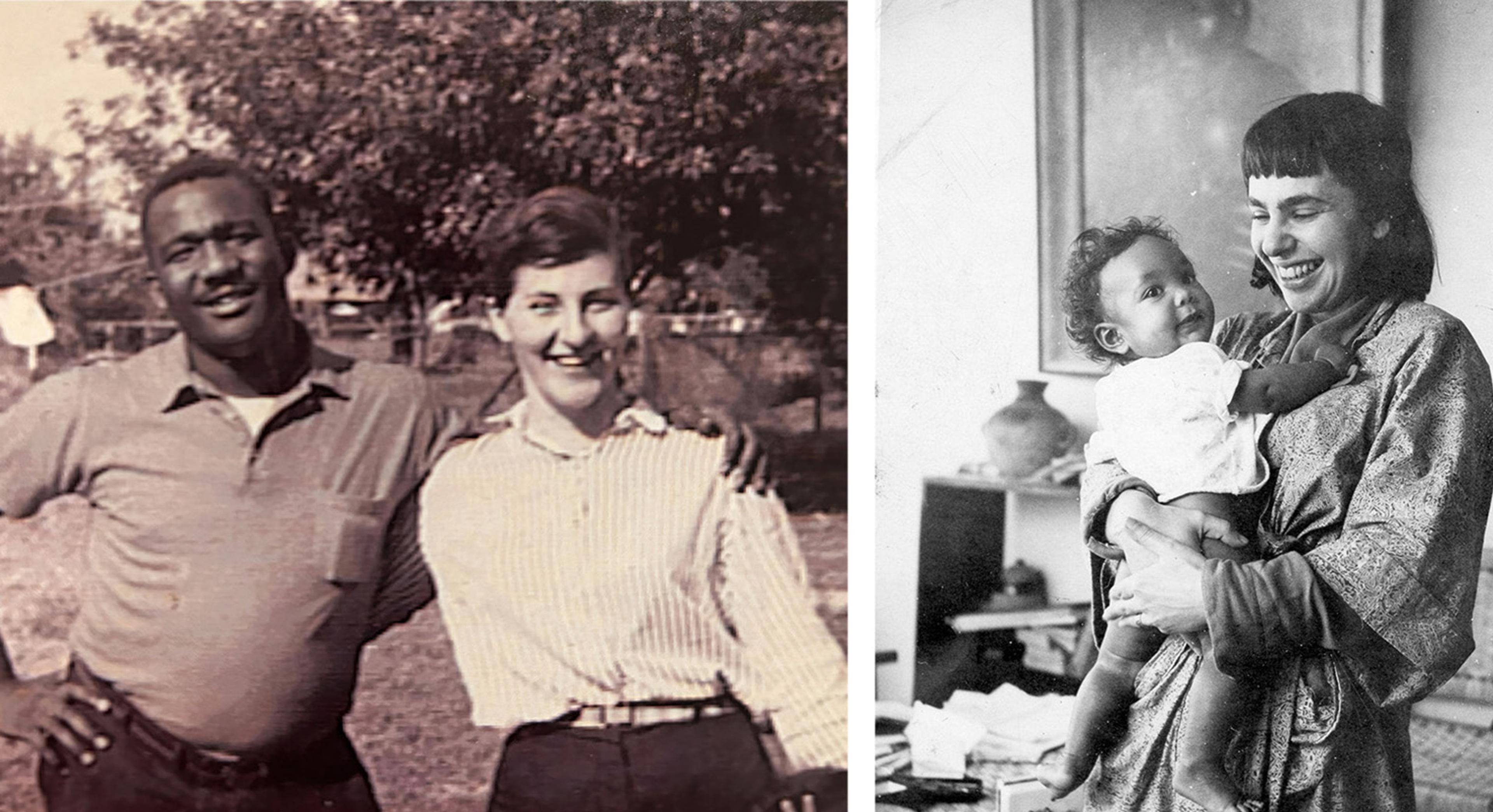

As an art historian, I would not normally write in the first person; I’ve always prided myself on my scholarly detachment and objectivity. However, because my family shares so much in common with that of the artist John Wilson (1922–2015), I feel compelled to deviate from the stock formula for this essay—coauthored with my sister, Leslie—on Wilson’s treatment of the subject of the Black family, especially mothers. Like Wilson and his wife, Julia, our parents married as an interracial couple during the first decade of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s.

Left: Duane and Joan Farrington, about 1956. Courtesy of Lisa and Leslie Farrington. Right: Julia Wilson holding Becky at four and a half months, Mexico, 1953. Courtesy of the Wilson family

Like Julia, our Irish mother attended the City University of New York (Brooklyn and Queens Colleges, respectively). Both Wilson and our dad were first-generation Americans (our grandfather emigrated to the US from the West Indies, Wilson’s father from Guyana). And, like Wilson and his wife, when our family traveled to the American South, we did so in separate cars because interracial marriage was still illegal in thirty states until midcentury. Fourteen of those states repealed their antimiscegenation laws between 1948 and 1967, but another sixteen states held fast to their racist legislation until the laws were forcibly overturned by the Loving v. Virginia Supreme Court case in 1967.[1] On the one occasion when Leslie and I traveled south as toddlers, I traveled with my father because I had brown skin; because my sister had white skin, she traveled with my mother.

John Wilson (American, 1922–2015). Julie and Becky, 1956–78 Oil on canvas, 38¼ × 28¼ in. (97.2 × 71.8 cm) Collection of Julia Wilson

As was the case with the Black mothers who were our neighbors, our mom had to focus on protecting her children, especially her son—my younger brother—from being arrested, mauled, or murdered by gang violence or by members of the New York City Police Department. By the time our brother was a teenager, in New York City, Blacks made up 19 percent of the population, but accounted for 59 percent of fatal police victims.[2] Our mother actually drilled my brother on how to speak to the police in order to avoid being beaten, arrested, or shot: with excessive deference, dropping the name of his congressman. As they raised their Black children in the 1960s and ’70s, our parents, the Wilsons, and Black parents nationwide shared an intense fear and worry for their family’s safety. Not much has changed since.

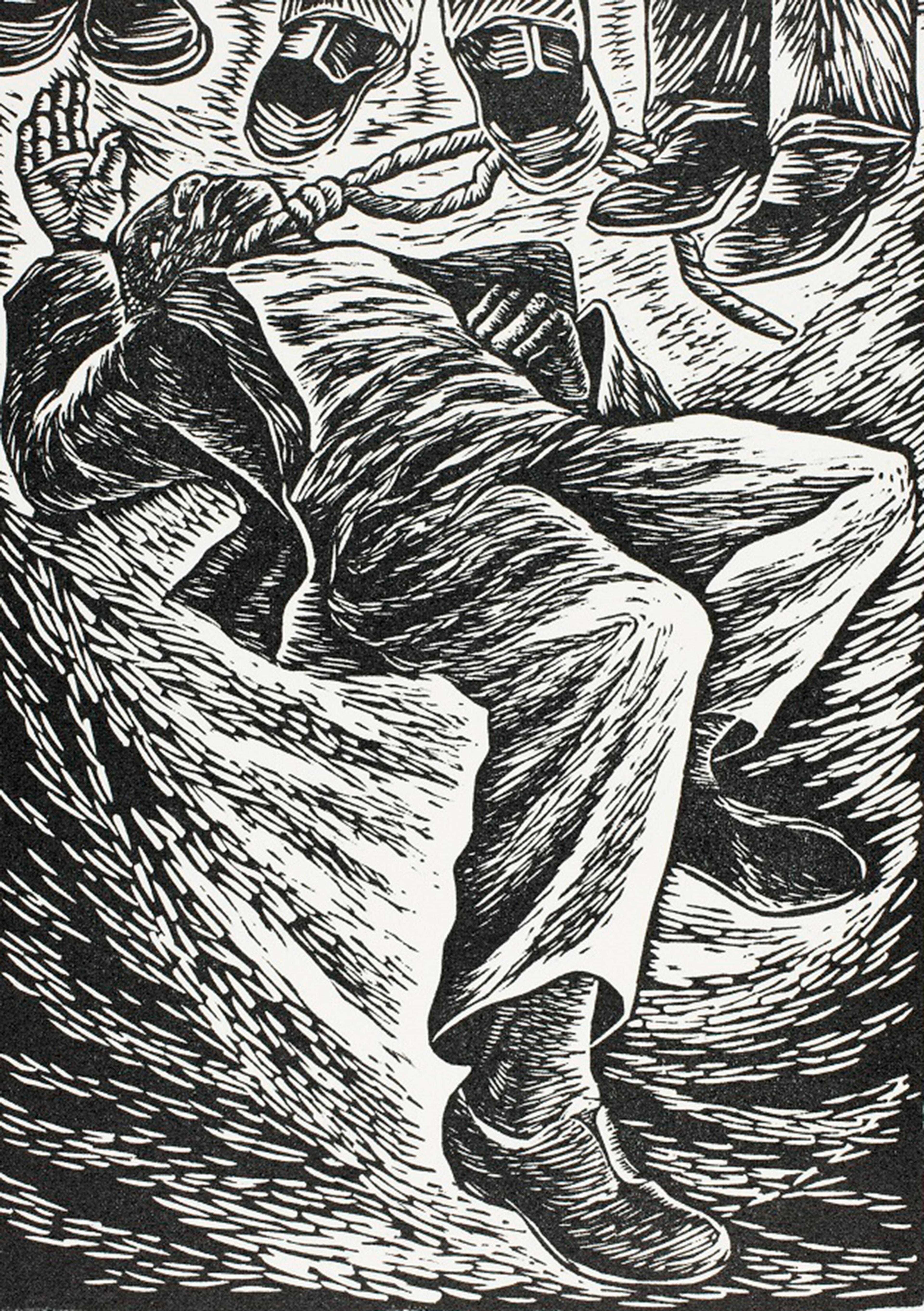

Elizabeth Catlett (American and Mexican, 1915–2012). And a Special Fear for My Loved Ones, 1947. From the series The Negro Woman (The Black Woman), 1946–47. Linocut, 15¼ × 11¼ in. (38.5 × 28.5 cm). Gift of Richard and JoAnn Edinburg Pinkowitz, 2024, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2024.69.93). © 2024 Mora-Catlett Family / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

And a Special Fear for My Loved Ones is the title for Elizabeth Catlett’s iconic print of a lynched Black man from her 1946–47 series The Negro Woman. The print is one of several works by Catlett that, like Wilson’s lost mural, The Incident (1952), addresses racism and its devastating effects on the Black family. Wilson knew Catlett and spent time working with her in the 1950s at the Taller de Gráfica Popular in Mexico, an artists’ commune that created graphics in support of labor unions and other leftist causes. Catlett is significant with respect to Wilson not only because she portrayed the effects of white violence on the Black family but because, like Wilson, she did so at midcentury, before racial violence became a ubiquitous theme in Black art.

Prior to the 1960s, few others chose this subject matter, with notable exceptions such as Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), who, in one panel of his 1941 Migration Series, depicts a race riot (though not in the context of its effect on the family), and Meta Fuller (1877–1968), whose sculpture In Memory of Mary Turner (1919) portrays a Georgia woman who, in 1918, was lynched while pregnant, set on fire, and repeatedly shot, and whose unborn child was cut from her belly and stomped to death.[3]

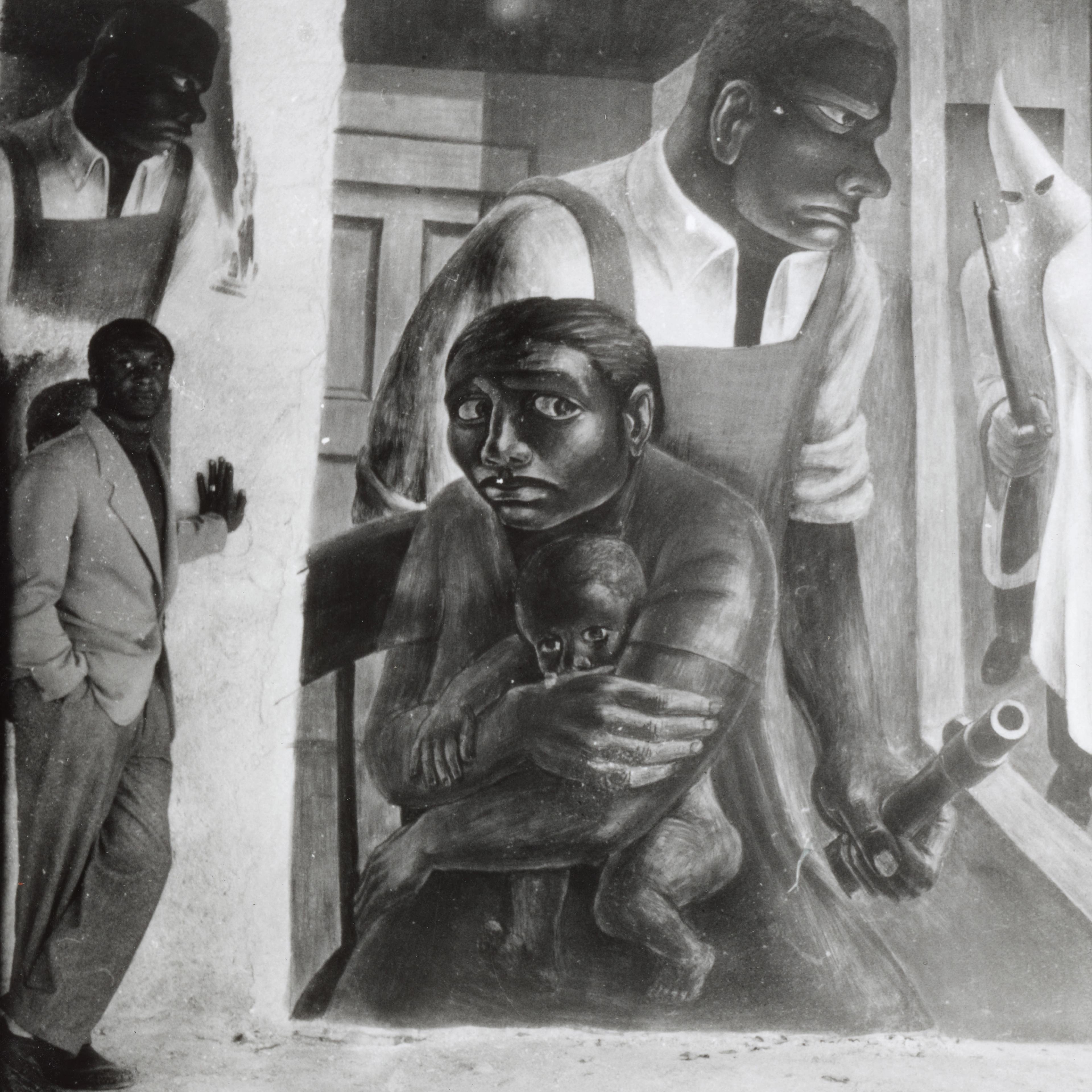

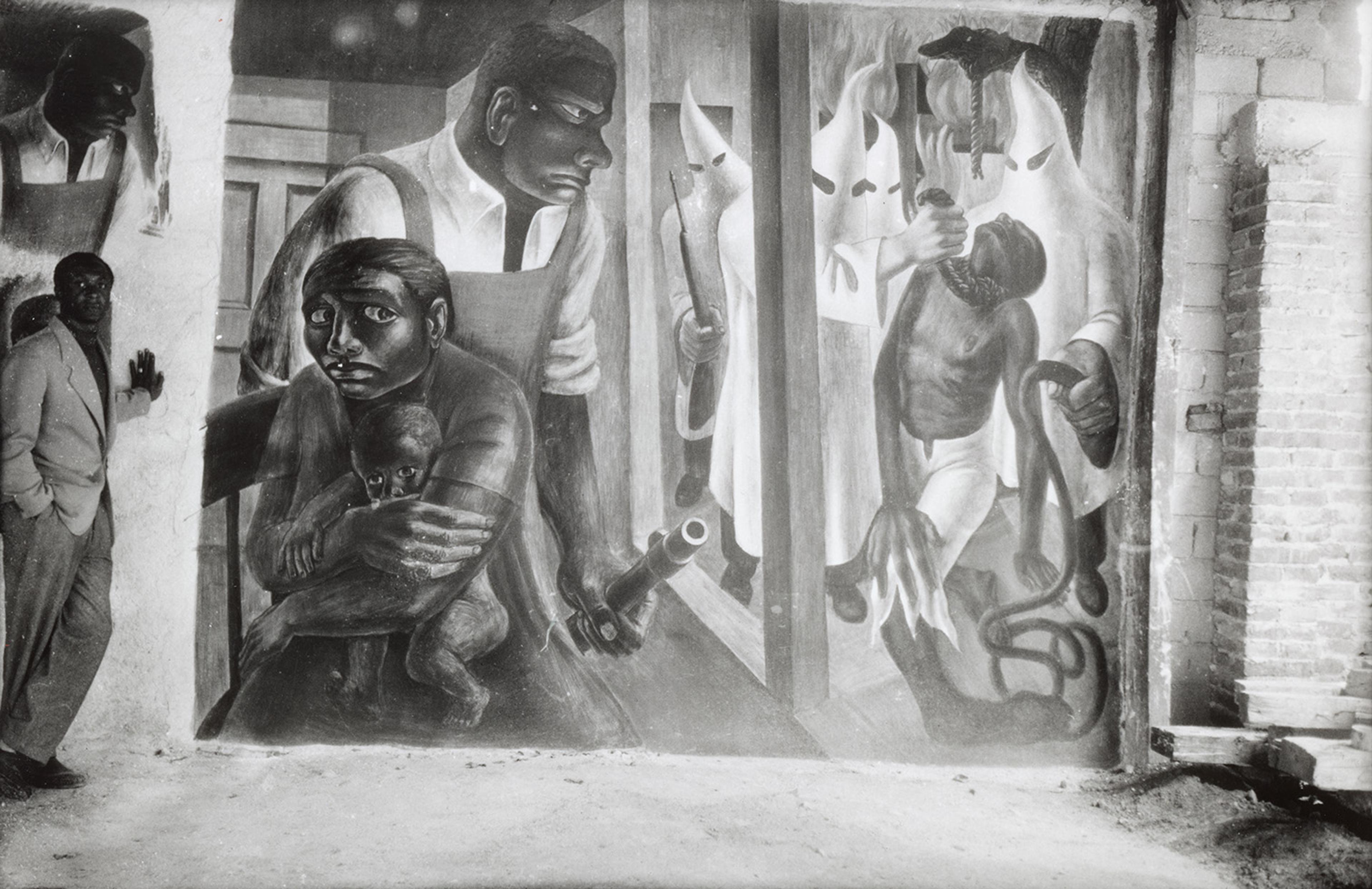

John Wilson’s The Incident in Mexico City, 1952

Wilson’s The Incident is more explicit than those of both Fuller and Catlett. Fuller’s sculpture, for instance, transforms a brutally violent incident into an elegant homage to sorrow and silence, far removed from the cold-blooded callousness of Turner’s murder; Catlett’s print shows only the fallen Black man and the shod feet of his attackers. By contrast, Wilson’s mural—preserved in various compositional studies for the piece—depicts the visceral image of a lynched man in a noose that has just been severed and is now gripped in the large white fist of a hooded Klansman, who holds his victim aloft, as if admiring his handiwork.

This aspect of the portrayal alone, however, does not set Wilson’s work apart from other artworks depicting lynch victims. Wilson chose to juxtapose this scene against that of a Black home, protected by its patriarch, who holds a rifle and glares menacingly through his window at the violence outside, as if daring the marauders to cross his threshold. He towers over his seated wife, who faces away from the window, clutching her newborn. The infant’s skin is incongruously pale against the dark skin of the parents—a choice that makes perfect sense if we consider that the artist anticipated being the father of biracial children.[4]

Left: Henry Ossawa Tanner (American, 1859–1937). The Banjo Lesson, 1893. Oil on canvas, 49 × 35½ in. ( 124.5 × 90.2 cm). Hampton University Museum, Hampton, VA, Gift of Robert C. Ogden. William H. Johnson (American, 1901–1970). The Home Front, about 1942. Oil on plywood, 39½ × 31⅜ in. (100.3 × 79.8 cm). Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, 1967.59.578. Image courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC / Art Resource, NY

Wilson’s depiction of the Black family in The Incident bears comparison to that of other key African American artists who also rendered images of the subject prior to the 1960s. Among them are Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937), whose Banjo Lesson (1893) and The Thankful Poor (1894) exemplify quietude, spirituality, and familial intimacy; Palmer Hayden (1893–1973), whose Janitor Who Paints (about 1930), like Wilson’s The Incident, includes a Black mother and child but, unlike Wilson’s work, depicts a calm and comforting family environment devoid of concern for the outside world; William H. Johnson (1901–1970), whose Home Front (about 1942) personifies stoicism and dignity amid poverty, but which is equally self-contained; and Charles White (1918–1979), whose Ye Shall Inherit the Earth (1953) portrays a heroic father and child cocooned by a halo of light against a nebulous background.

Charles White (American, 1918–1979). There Were No Crops This Year, 1940. Graphite on paper, 28¾ × 19¼ in. (73 × 48.9 cm). Private collection © The Charles White Archives

The vast majority of such portrayals, particularly before the height of the Civil Rights Movement and subsequent Black Power Movement, eschew the conflation of family and fear of external violence—even though the latter has long been a reality of Black life. Charles White’s 1940 drawing There Were No Crops This Year offers an alternate view: the monumental couple’s distress over impending starvation suggests true despair for the future of their family while alluding to starvation, a type of passive violence that, in its potential to kill, would have been as effective as any lynch mob.

Isolating, for a moment, the mother and child from Wilson’s larger composition, it becomes evident that his treatment of this pair sets him further apart from his cohorts. The mother in The Incident looks askew, her large black eyes focused both over her shoulder and straight ahead, suggesting more than one enemy. Her left eye swivels in the direction of the window where the lynching has occurred. With her right eye, she stares out at the viewer, engaging the audience directly. Her foci invite the audience to feel what she feels—fear and foreboding—even as it silently implicates all those who are aware of white-on-Black violence but do nothing about it.

Wilson’s mother does not hold her infant gently in her arms, but rather in a vise-like grip designed to prevent the infant from being torn from her arms. This gesture alludes to the myriad moments throughout the life of the child when it might be taken from her—a potentiality foreshadowed by the adult male lynch victim outside of the window. Furthermore, the way the mother holds her child—pressing it into her abdomen—can be interpreted as a Freudian desire to return it to the safety of the womb—the only place where she believes he is truly protected from harm. Even the womb is not necessarily a haven for Black children, as made evident by the brutal murder of Mary Turner and her unborn infant.[5]

Meta Fuller (American, 1877–1968). Sorrow, about 1934 Plaster bookend, painted gold, 15 × 5¼ × 4¼ in. (38.1 × 13.3 × 11.4 cm). Private Collection, Maryland Image courtesy Danforth Art Museum at Framingham State University, Gift of the Meta V. W. Fuller Trust

Again, Wilson’s representation deviates from those of any number of African American artists of the early to mid-twentieth century who turned their attention to the theme of Black motherhood, or the Black Madonna. In addition to Catlett’s many works in the genre, other examples are May Howard Jackson’s (1877–1931) sculpture Mulatto Mother and Child (before 1931) and Meta Fuller’s Sorrow (1934). Jackson swathes her newborn in the long voluminous tresses and folded arms of its mother, invoking a womb space as Wilson does in The Incident. Fuller’s Sorrow likewise alludes to a uterine enclosure for the child; the seated mother is doubled over her toddler in an effusive kiss and embrace.

What these two examples and the plethora of others—including the Gothic and Renaissance precedents upon which so much of the genre is based—do not articulate is the trepidation and sense of impending doom that we see in Wilson’s mother. Historically, Madonna and Child images tend toward the beatific, the mother’s serene beauty and love for her child the central foci. Even pietà images, which depict the Madonna mourning the death of her son, preclude any expression of fear or foreboding, as the alluded-to martyrdom has already taken place. By comparison, the sober presence of mind of Wilson’s mother, her accusatory gaze implicating the audience, is nothing short of remarkable. With this persona, Wilson reifies the very real epidemic of “obstetric violence” that plagues women of color in alarming numbers, victimizing them and their children even before birth.

— Lisa Farrington

White Supremacy, Obstetric Harm, and the Mother-Infant Dyad

Motherhood is celebrated, cherished, and enjoyed in peaceful times and safe environments. To bear children, nurture, and love them is a gift, a joyful birthright, that comes with being a woman—for many women. Wilson’s The Incident illuminates how, for Black women, childbearing is complicated by racial oppression, terror, and the devaluing of Black lives by the dominant white supremacist culture.

John Wilson (American, 1922–2015). Study for The Incident, 1952. Opaque and transparent watercolor, ink, and graphite on paper, 17 × 21 ¼ in. (43.2 × 54 cm). Yale University Art Gallery, Janet and Simeon Braguin Fund, 2000.81.1

In Wilson’s scene from inside the home of a Black family witnessing a lynching, we see fear in the mother’s eyes and tension in her hunched shoulders as she clutches her baby tightly with larger-than-life forearms and hands. The vulnerability of mother and child is emphasized by their small scale in comparison to the father, who stands behind them with a defensive weapon.

Farrington children, from left to right: Leslie, Duane, and Lisa, about 1960

As a Black mother and medical doctor, I have a visceral reaction to this scene because it stirs up a deep sensitivity—developed in childhood—to racial injustice, which here is perpetrated both on the victim of the lynching and on the family terrorized by it. As a Black obstetrician, I grieve the physical and psychological harm of the toxic stress of racism on the mother-infant dyad Wilson portrays—an ongoing harm made manifest in the maternal health crisis of the present-day United States.[6]

Lynchings of various forms are still happening through racial profiling, police killings of unarmed people, wrongful convictions, white vigilante violence, 911 calls for “living while Black,” and “obstetric violence” experienced by Black mothers seeking maternity care.[7] Toxic stress also results from forms of exploitation consistent with modern-day slavery. Essential workers were forced to clock in during a pandemic, incarcerated persons perform unpaid labor in prison, and those living in under-resourced redlined neighborhoods with polluted air and water often require two to three jobs to remain housed. Research shows that racial bias poisons all aspects of life: hiring, real estate, banking, education, medical care, social services, and more.[8] Social injustice, especially racism and sexism, fuels the maternal health crisis in the United States.

For much of my career as an obstetrician-gynecologist, my awareness of how racism negatively impacts health was minimal. Between my medical education in the 1980s at Howard University and my adopted home, the predominantly Black city of Washington, DC, I was enveloped in a cocoon of freedom from contemplating racism. Its impact on health was not a topic of study in medical education or training except for the concept that lack of insurance, poverty, and substance abuse were known to cause poor health outcomes. I knew that overt racism and discrimination affected the medical treatment of poor Black folks, but I thought that happened mainly in the South. After medical school, I returned home to New York with an idealistic vision of serving the community in which I grew up.

I did not realize then that the disparaging remarks about patients of color made by white medical professionals in New York City hospitals were indicative not only of thinly veiled prejudice, but also of unequal treatment. In my experience, doctors think they know best, and they think they do their best to care for people. If something goes wrong, they tend to find fault with their patients. If a patient “uses drugs,” doctors are quick to blame them for poor outcomes. If a patient cannot recite their medical history to their doctor’s satisfaction, they are a “poor historian”; if they miss appointments, they are noncompliant. Premature birth or stillbirth prompts a search for infection or illicit drug use—called “mother blame” by reproductive justice activist and scholar Monica McLemore.[9] Many physicians’ lack of cultural sensitivity and self-awareness of biases and stereotypes is often alarmingly apparent to those whom they pledge to do no harm.

The miseducation of doctors and nurses is rooted in white supremacist pseudoscience—developed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and used to justify slavery—which asserts that Black people are inferior, with deficient bodies, thicker skin, less sensitivity to pain, and prone to bad habits. These ideas persist in medical education even today and lead to substandard care, poor outcomes, and mistrust in the health-care system.[10] I became aware of medical racism thirty years after graduating from medical school, when public health data revealed serious deficiencies in the care provided by obstetricians to mothers in the United States, and efforts were begun to examine and correct the causes of rising maternal mortality and severe morbidity.

In 2014, at a meeting of the new Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health, I learned that maternal mortality in the United States had doubled since the 1990s and was three to six times worse than other well-resourced nations.[11] I also learned that ninety percent of babies born in the United States were delivered by obstetricians, while all other nations’ births were attended predominantly by midwives. The midwifery model involves support for the physiology of spontaneous birthing, with fewer interventions like cesarean sections (surgical births) and much lower costs of maternity care. In the early 1900s, doctors and hospitals in the US orchestrated a campaign against midwives, virtually eradicating the centuries-old tradition in the Black community.[12] American mothers are still paying for the medicalization of birth by the for-profit medical industry.

Most disturbing for me was the experts’ report that Black women were three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than non-Blacks. They were especially puzzled that Black mothers were more likely to die regardless of socioeconomic status, educational level, or comorbidities. I was so alarmed by these findings that I called my sister, Lisa. With certainty and without hesitation, she told me in two words the reason Black women were experiencing poor outcomes, no matter their health or wealth: “It’s racism!” The next day, I blurted out these two words to the experts, and they looked at me with blank stares—like I was speaking a strange language. Lisa’s decades of study of African American art history and culture and her lived experience of racism made the answer obvious to her, while it would take years for medical “experts” to see the truth. Even now, many physicians are still blaming mothers for poor birth outcomes.

Mirroring the fear of racialized violence that the mother in Wilson’s The Incident experiences, Black mothers are afraid and mistrustful of the medical system due to centuries of mistreatment.

As recently as September 2023, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention survey of Black mothers revealed that thirty percent experienced mistreatment in the form of verbal abuse, dismissal, neglect of their conditions, and coercion to undergo unwanted interventions—all of which are forms of obstetric violence and which increase the risk of complications, birth trauma, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Mirroring the fear of racialized violence that the mother in Wilson’s The Incident experiences, Black mothers are afraid and mistrustful of the medical system due to centuries of mistreatment, including the criminalization of pregnant and birthing individuals and their partners beginning during slavery and arguably worsening in recent years with the restriction of access to abortion-related services in mostly southern states with large Black populations.

Maternal mortality and severe morbidity are expected to rise with the lack of appropriate care for miscarriages, nonviable pregnancies, and restricted access to abortion for those at risk of pregnancy complications. In addition, there is the threat of policing mothers who assert their right to bodily autonomy and make informed choices that go against medical advice. In some instances, medical professionals make allegations of child abuse and call Child Protective Services (CPS), disproportionately targeting Black families.[13] CPS has the power to take children from their mothers—a practice reminiscent of babies being sold away from mothers in slavery.

African American scholars, journalists, and artists have been exposing the causes of shortened life expectancy, excess maternal and infant mortality, and stress-related conditions since 1903, when W. E. B. Du Bois wrote The Souls of Black Folk. Later, in 1994, twelve Black feminists started the Reproductive Justice Movement, stating that all women have human rights to (1) have children, (2) not have children, and (3) to nurture their children in safe and healthy environments.[14] Reproductive Justice seeks to end racial oppression and assert the human right to joyful and safe childbearing. This has become my life’s work: educating Black mothers, their partners, and their supporters about their right to self-determination and autonomy and how they can assert those rights in medical and maternity settings.

Wilson poses with The Incident in Mexico City, 1952

John Wilson’s depiction of the terror experienced by an African American family epitomizes the stress of living while Black in America—always at risk of disrespect, injustice, and death at the hands of non-Black Americans who want to control their lives, their joy, and their excellence, so they can see themselves as more powerful, superior, and safe. My sister and I hope that white viewers of Wilson’s work and that of other African American artists might experience an awakening of their senses of empathy and of our shared humanity, and be motivated to end racism in America. Racism is their ailment to heal so that they might become whole members of the human family.

— Leslie Farrington

This essay is adapted from the catalogue Witnessing Humanity: The Art of John Wilson, which accompanies an exhibition on view through February 8, 2026.

Notes

[1] Loving v. Virginia, 388 US 1 (1967); Bárbara C. Cruz and Michael J. Berson, “The American Melting Pot? Miscegenation Laws in the United States,” OAH Magazine of History 15, no. 4 (2001): 80–84.

[2] John S. Goldkamp, “Minorities as Victims of Police Shootings: Interpretations of Racial Disproportionality and Police Use of Deadly Force,” in Readings on Police Use of Deadly Force, ed. James J. Fyfe (Police Foundation Office of Justice Programs, 1982), 128–51.

[3] Christopher Meyers, “Killing Them by the Wholesale: A Lynching Rampage in South Georgia,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 90, no. 2 (2006): 214–35; Julie Buckner Armstrong, Mary Turner and the Memory of Lynching (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011).

[4] Based upon the “one drop theory,” which arguably persists today, when it comes to African Americans, biracial equals Black.

[5] Timofei Gerber, “Eros and Thanatos: Freud’s Two Fundamental Drives,” Epoché, February 2019; Otto Rank, The Trauma of Birth [translator unknown] (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co., Ltd., 1929).

[6] Jamilla Taylor et al., “The Worsening U.S. Maternal Health Crisis in Three Graphs,” Healthcare Commentary, Century Foundation, March 2, 2022.

[7] Cara Terreri, “What Is Obstetric Violence and What If It Happens to You?” Lamaze International, July 20, 2018.

[8] National Public Radio (NPR), Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, “Discrimination in America: Final Summary,” January 2018; Delia O’Hara, “David Williams Studies Health Disparities in America,” American Psychological Association, 2018.

[9] Monica McLemore, “What Blame-the-Mother Stories Get Wrong About Birth Outcomes among Black Moms,” Center for Health Journalism, USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, March 4, 2018.

[10] Kelly M. Hoffman et al., “Racial Bias in Pain Assessment and Treatment Recommendations, and False Beliefs About Biological Differences between Blacks and Whites,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113, no. 16 (2016): 4296–301.

[11] Airis Y. Collier and Rose L. Molina, “Maternal Mortality in the United States: Updates on Trends, Causes, and Solutions,” Neoreviews 20, no. 10 (2019): e561–e574.

[12] Phyllis L. Brodsky, “Where Have All the Midwives Gone?” Journal of Perinatal Education 17, no. 4 (2008): 48–51.

[13] “The Family Regulation System: Why Those Committed to Racial Justice Must Interrogate It, Harvard Civil Rights–Civil Liberties Law Review, February 17, 2021.

[14] Loretta Ross, “Understanding Reproductive Justice: Transforming the Pro-Choice Movement,” Off Our Backs 36, no. 4 (2007): 14–19.