What do an unknown Renaissance beauty and Jean Harlow have in common? They are both part of a constellation of blonde women in The Met collection, images that belong to a long Western iconographic tradition associating blonde hair with femininity, purity, desire, and Whiteness. From fairytales to Hollywood, blondeness has been associated with beauty and light, an apparently timeless symbol of ideal femininity. Despite its mythic status, however, the history of blonde tells us much about history and society, revealing changing attitudes toward women, race, class, and national identities. This article examines blonde beauty shaped in earlier centuries and then considers a particular moment, after the end of World War II, when the prevailing image of Hollywood glamour was exported to Britain and given a distinctively British twist.

Blondeness is an effect of light rather than of color. It is a sign of radiance, brilliance, and glow, which draws on Christian iconography. In the thirteenth century, Saint Clare of Assisi relinquished the material world to establish a religious order based on a rule of strict poverty. She symbolized her commitment to this ideal by cutting her hair, an act made more radical by her representation within hagiographies as having long, thick, blonde tresses. Blondeness has been admired in Western myth, religion, and secular culture as a symbol of luminosity and distinction—of purity, as well as desirability.

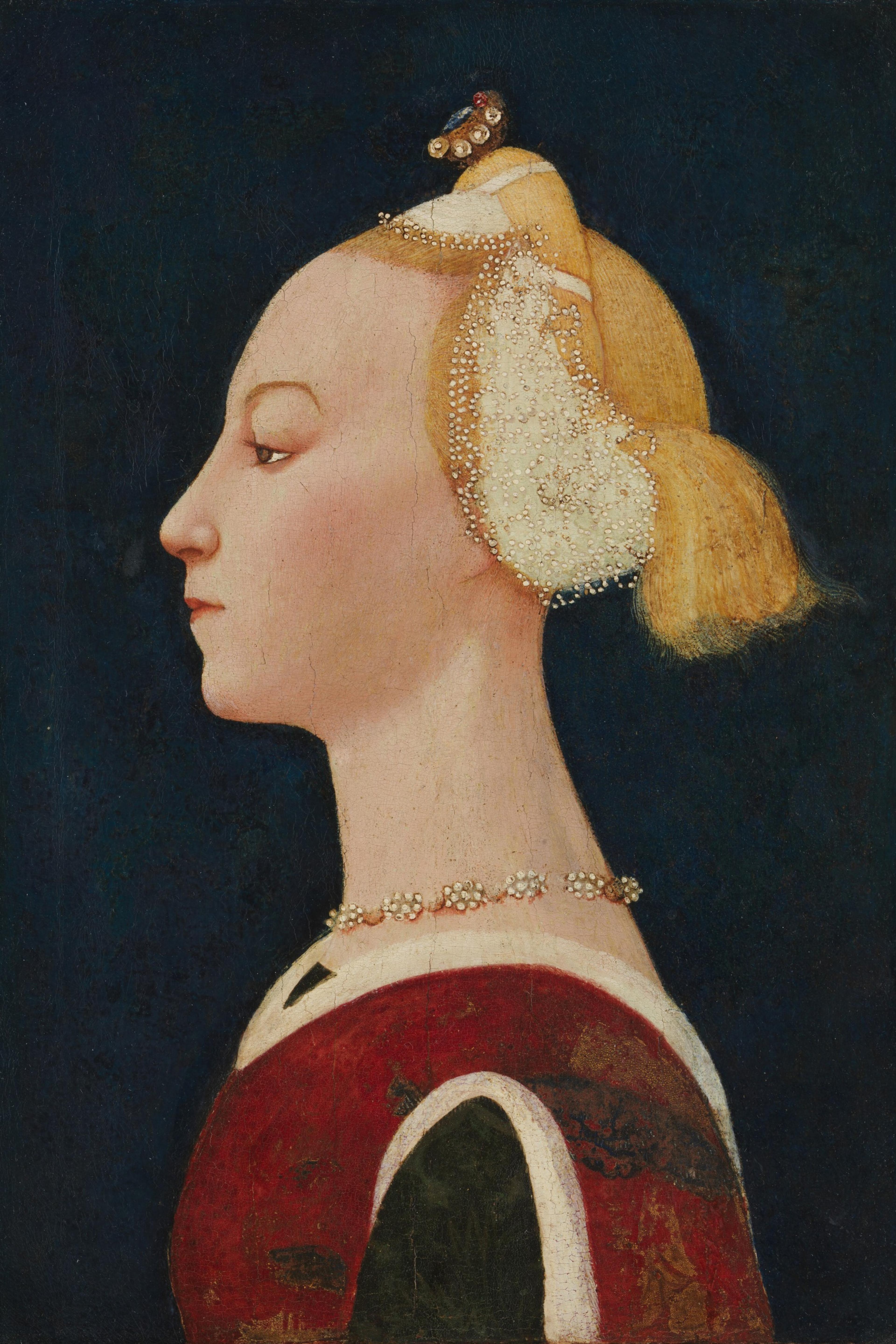

Master of the Castello Nativity (Italian, active ca. 1445–75). Portrait of a Woman, Probably 1450s. Tempera and gold on canvas, transferred from wood, 15 3/4 x 10 3/4 in. (40 x 27.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jules Bache Collection, 1949 (49.7.6)

For instance, a small profile portrait of a woman, attributed to the Master of the Castello Nativity and dated around the 1450s, is set against a dark background; the face and neck are sharply highlighted, almost glowing, but the blonde, golden hair is the most captivating feature with its elaborate styling. Tiny pearls accentuate the hairline and headdress, and the hair itself is wrapped and folded in a visual display of this anonymous woman’s status. Painted in tempera and gold, it is hard to pick out specific passages and highlights of gold, as this is a golden woman who radiates social significance through her hair.

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (French, 1755–1842). Peace Bringing Back Abundance, 1780. Oil on canvas, 41 × 52 in. (103 cm × 133 cm). Musée du Louvre, Département des Peintures, Paris, France

Blonde femininity continued to appear in Western visual art. In Elizabeth Vigée Lebrun’s allegorical painting Peace Bringing Back Abundance (1780), which she submitted as her reception work to the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in 1783, Peace is represented as a clothed female figure with dark hair escorting Abundance, who is depicted as partially nude with extravagant blonde hair. Everything about this latter figure conveys a sense of plenty: the cornucopia of fruits, flowers, and cereals at her waist and woven into her hair; the fleshy, white skin and rosy cheeks; the exposed breast; and, above all, by the golden locks that cannot be contained by the elaborate plaited style, escaping in tendrils around her neck and over her left shoulder. Abundance must be blonde to set off the sobriety and dignity of Peace and to personify its fulsomeness and material bounty.

Although different formulas were used to lighten hair from the classical period onward, blonde glamour came into its own in the early twentieth century with the introduction of cheaper, modern chemical hair dyes. The range of blonde shades was expanded to include platinum blonde, achieved with bleach and hydrogen peroxide, which strips the hair to create a white-blonde appearance that Hollywood filmmakers quickly adopted in the 1920s and '30s. New film and lighting technologies captured the lightest of blonde hues and the bombshells who sported them, with all their complex associations of racial purity, mystique, and sexuality.

Left: George Hurrell (American, 1904–1992). Jean Harlow, 1932. Gelatin silver print, 12 15/16 x 9 15/16 in. (32.9 x 25.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987 (1987.1100.430). Right: Edward J. Steichen (American (born Luxembourg), 1879–1973). Mae West, 1920s–30s. Gelatin silver print, 9 9/16 x 7 9/16 in. (24.3 x 19.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Edward Steichen by direction of Joanna T. Steichen and the International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House, 1983 (1983.1158.12)

There are many examples of blonde film stars from this period in The Met's Department of Photographs. A 1932 portrait of Jean Harlow by George Hurrell shows the iconic actress with her signature white curls framing her face, eyes gazing up at the viewer, a half-smile curling the corners of her mouth. It is provocative, but with a faux naivety that defines the American twentieth-century pin-up. Far more knowing are the look and pose in Edward J. Steichen’s portrait of Mae West, in which she is shown adorned with glittering jewelery and framed by an extravagant black lace ruff. What sets West apart from other Hollywood blondes is her parodic performance style; she embodies camp humor and resists objectification through her assertive presence.

By the Second World War, blonde femininity was the definitive look of contemporary female glamor, disseminated through film, magazines, and advertisements. Hair dyes were increasingly available and aggressive marketing campaigns targeted female consumers. One of the most successful campaigns of the period was created by an American copywriter Shirley Polykoff for the hair-coloring company Clairol. Originally a French dye process called Auréole (aura of light), it was brought to the United States in the 1950s where it was manufactured using French formulas and distributed as a new home hair-coloring product throughout America and Europe. Polykoff came up with the brilliant tagline “Does she…or doesn’t she?”—suggesting, with teasing innuendo, that the new blonde hair dye is so natural you cannot be certain whether a woman’s hair is dyed. Further Polykoff campaigns centered around the slogans “Is it true blondes have more fun?” and “If I’ve only one life, let me live it blonde.” Polykoff modernized the image and branding of dyed blonde, making it more respectable while retaining its sense of fun and desirability.

And so the stage was set for the appearance of the most iconic American blonde, Marilyn Monroe. Monroe perfectly embodied postwar American prosperity and global glamour, presenting a flawless feminine masquerade that draws on and exceeds the history of blondeness. Monroe’s biography and struggles with the Hollywood film industry are more familiar today than they were during her career. Monroe catapulted to stardom with Howard Hawks’s Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), adapted from Anita Loos’s 1925 novel of the same title. Monroe plays a showgirl whose goal in life is to have a rich husband who can satisfy her love of expensive clothes and jewelry. Dressed in a sleeveless, tight-fitting pink satin dress with shoulder-high matching gloves, she performs the quintessential “dumb blonde,” a stereotype that she would rebel against until her premature death in 1962.

Andy Warhol (American, 1928–1987). Untitled from Marilyn Monroe, 1967. Screenprint, 36 x 36 in. (91.5 x 91.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John B. Turner Fund, 1968 (68.627(3))

Andy Warhol famously drew on the image of Monroe from the year of her death in Untitled from Marilyn Monroe (1967). The print was made to promote a ten-print portfolio of Monroe, each an intense close-up of her face in different vivid Pop color palettes. The 1967 announcement print emphasizes the flawless, made-up face of Monroe—a signature look meticulously developed by her make-up artist Allan "Whitey" Snyder. Warhol’s print accentuates Monroe’s eyes, mouth, and hair, which are highlighted in bright yellow against a pink background and the turquoise blue of her face. Monroe is a blonde Pop princess, a commodity like a can of Campbell’s soup, that can be repeated and sold again and again.

Monroe’s rise to fame in the 1950s was closely reported across the pond in Britain, making blondeness a transatlantic story. In the postwar years, American glamour was exported to Britain as part of a larger flow of commodities that crossed the Atlantic while Britain slowly recovered from the war and sought to modernize. Glamour from the United States was a composite of images and goods, promoted through new modes of advertising to British audiences weary of austerity and shortages: it represented luxury and abundance, dazzling surfaces, visual spectacle, and sex.

Image of Diana Dors taken by Carl Sutton in 1954. Courtesy Getty Images

In the passage of blondeness eastward across the Atlantic, something important happened: blonde became British. Subjected to the fault lines of British class, race, and gender, Marilyn Monroe inspired the British actress and singer Diana Dors, a figure who played a defining role in the nation’s distinct, postwar British identity. At a moment when the prewar empire was on the verge of collapse, and the impact of migration from the colonies was at its most intense, blonde British femininity was a complex sign of the White nation and its halting, difficult steps toward reconstruction.

Left: Advertisement for “Golden’ Shadeine”, Photoplay (March 1952). Right: Advertisement for “Hiltone”, Photoplay (August 1953)

Postwar blonde is a question of identity politics, sold to women through the dream of a perfect lifestyle. Blonde hair, it was claimed, could not only transform appearances: it could also change lives. As well as selling the fantasy of a life lived blonde, advertising also played on women’s fears of not looking glamorous, or of dyed hair reverting to an indifferent, mousy shade. “Mirror, Mirror on the wall…make me fairest of them all,” advised one advert for Hiltone hair dye. Failure was a continual threat, and postwar advertising campaigns drew on the image of blonde perfection to keep women in a state of self-doubt and insecurity. Hiltone even secured the rights to use Monroe’s image from Gentlemen Prefer Blondes in their advertisements, further pushing the message that blondes were more confident, successful, and attractive to men.

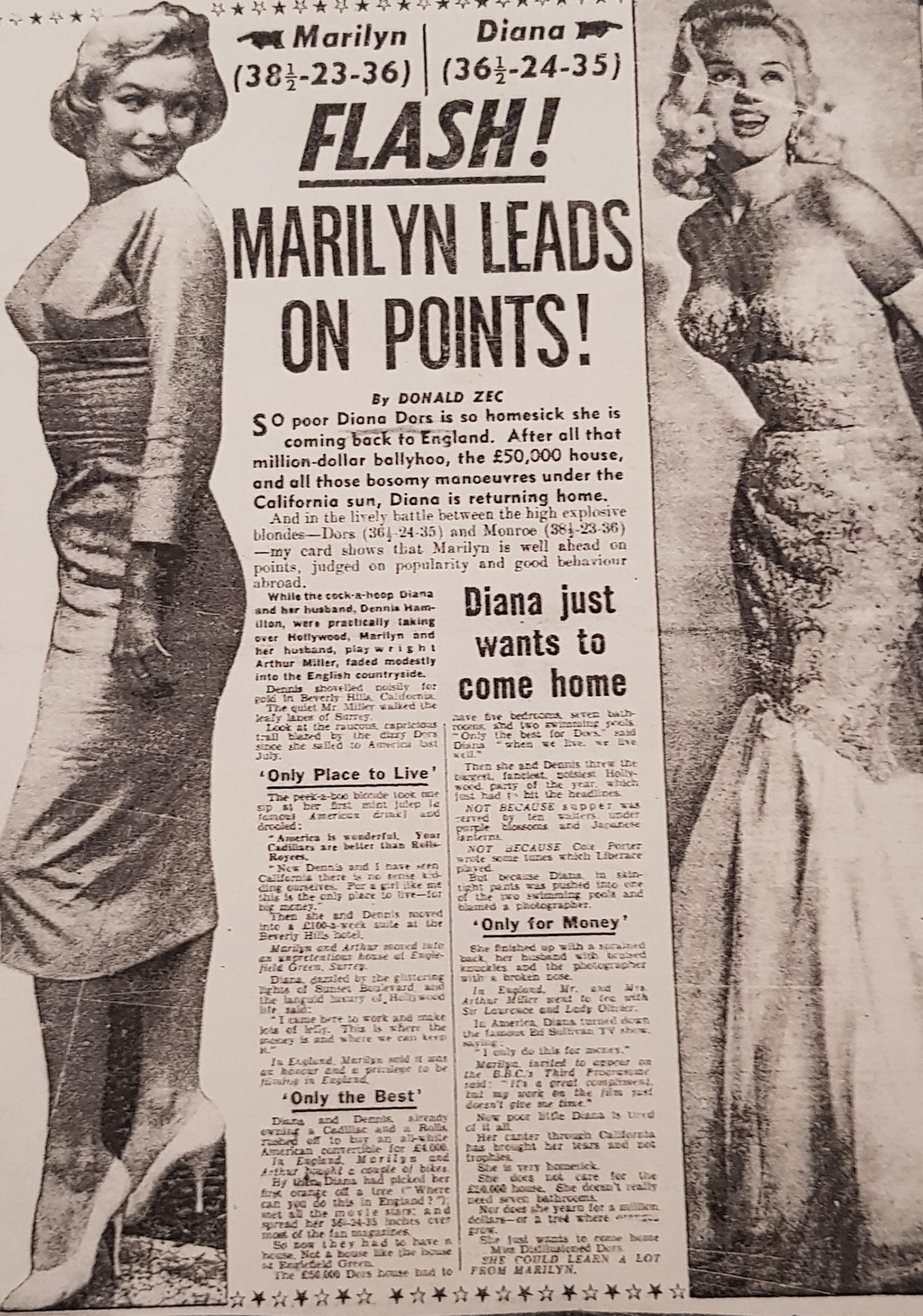

“Flash! Marilyn Leads on Points!,” Daily Mirror, September 29, 1956

Diana Dors developed and honed her blonde image over several years, modeled on the Monroe prototype but with a unique British sensibility. By 1956, Dors was ready to test her performance of brash affluence on American audiences. As one national newspaper put it, it was “The Battle of the Two Bombshell Blondes.” Breast, waist, and hip measurements were the ordnance between two glamour superpowers, and Dors had to prove that she was more than a poor copy, a vernacular version of a global prototype, that she could make the grade on the world stage.

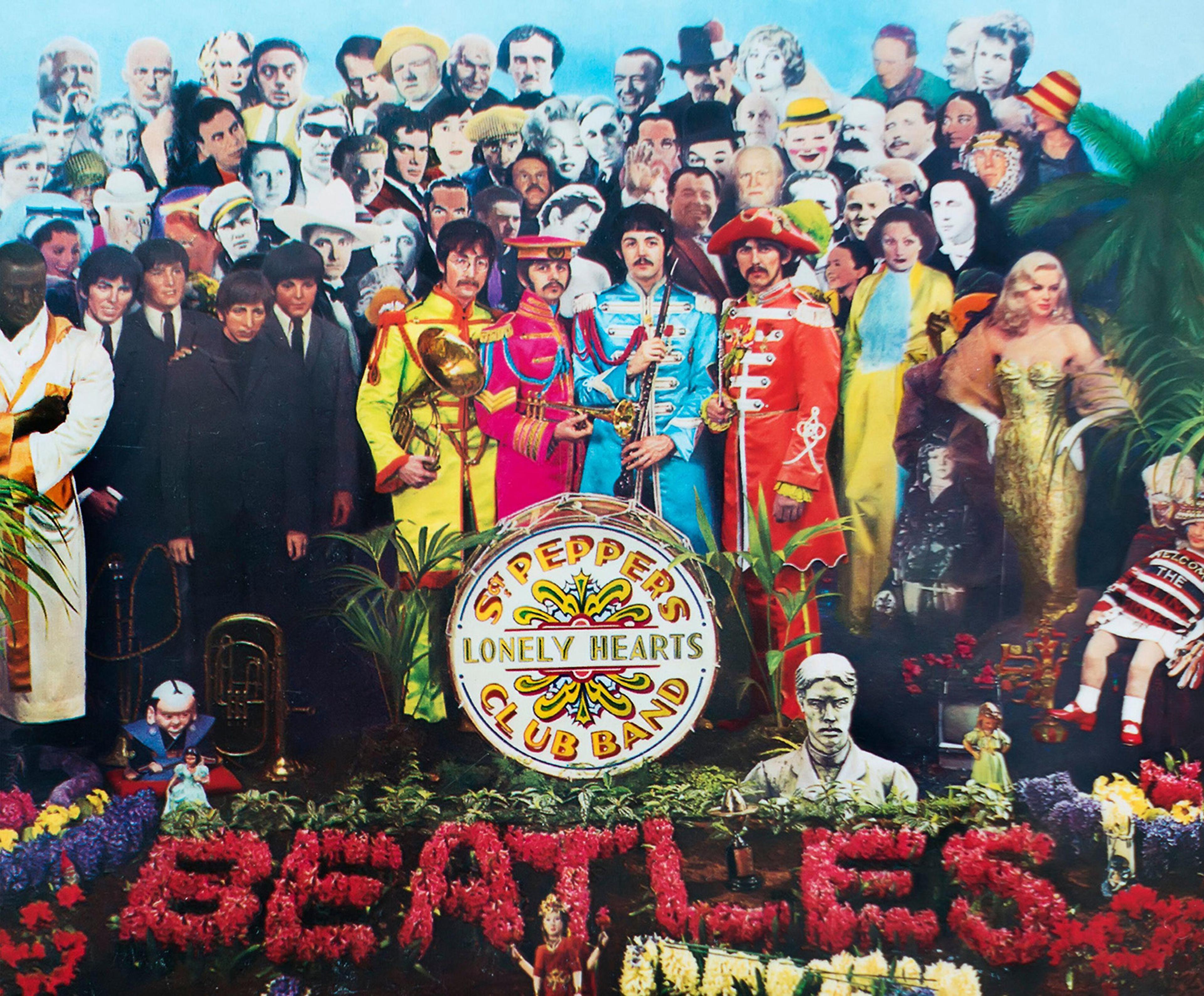

Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) by the Beatles. Courtesy Alamy Inc

Unfortunately, Dors’s time in Hollywood was not a success. A series of negative publicity stories culminated in a poolside fight at a party at her home, turning the American press and studios against her and ending her Hollywood dream. Dors and Monroe do turn up together in another context, however: the cover of the 1967 Beatles album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band by Peter Blake and Jann Haworth. The famous image shows a crowd of mythologized figures from religion, sports, literature, and popular culture. Their identities are provided in multiple sources, but another narrative is almost hidden among the crowd of figures. In the back row, the head of the wisecracking Hollywood blonde Mae West begins a diagonal line that continues to the center of the crowd with the face of Marilyn Monroe before proceeding on this axis to the full-length waxwork figure in the front row of Diana Dors. These three figures help tell the transatlantic story of blondeness as an export from the United States to its adaptation and reimagining in postwar Britain.