Introduction

540. Welcome (Mosaic with Preparations for a Feast)

Andrea Myers Achi, Mary and Michael Jaharis Associate Curator of Byzantine Art

ANDREA ACHI: Welcome to this fantastic, groundbreaking exhibition, Africa & Byzantium. My name is Andrea Myers Achi, and I am the Mary and Michael Jaharis associate curator ofByzantine art. The exhibition builds upon a long legacy of Byzantine exhibitions at The Met, and it connects North Africa and the Byzantine world between the fourth to the fifteenth century. You’re going to see works from Tunisia, Ethiopia, Egypt, Sudan, spanning from mosaics, textiles, manuscripts, jewelry, and small daily life objects, as well.

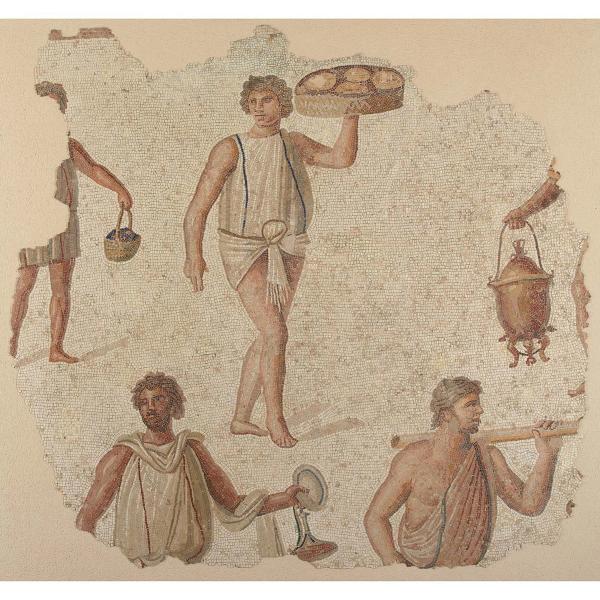

NARRATOR: During this period, North Africa included some of the wealthiest, most highly educated, and cosmopolitan provinces of the late Roman and Byzantine Empire. This intricate floor mosaic fragment from the late second century once belonged to the grand dining room or reception hall of a Tunisian villa, about as large as The Met's Great Hall.

Take a closer look at this busy scene.

ACHI: These men are preparing a feast for a festival. The first person you see is holding a breadbasket, you see four loaves of bread. And under him is a man who's holding a wine carafe,and then someone's holding something on his shoulders, meat or something very heavy. You also see other aspects of food and different containers.

You’re looking at men from all over North Africa and the Byzantine world. They look different because the skin is different, the hair texture is different. But it’s important to know that all of these people were Roman, and the Roman world was very diverse.

NARRATOR: Routes, over land and water, connected remote Egyptian oases to the Nile Valley and crisscrossed North Africa. They were linked by trade across the Mediterranean, sub-Saharan Africa, the Red Sea, India, and, more distantly, the Silk Roads. These routes dispersed people, materials, and ideas throughout the empire.

You’ll hear more about these rich interconnections from a variety of specialists, including members of the curatorial team, community advisors, and catalogue authors.

This audio guide is sponsored by Bloomberg Philanthropies and produced in collaboration with Acoustiguide.

In 330 C E, the Roman emperor Constantine moved the imperial capital from Rome to a city further east, Byzantion. The emperor’s “New Rome” (modern-day Istanbul) became popularly known as Constantinople. We use the term “Byzantium” to refer to the eastern Roman Empire, which ruled until the fifteenth century. Despite being a vast and historically significant empire that spanned parts of Africa, Europe, and Asia, Byzantium’s extensive connections to northern and eastern Africa are not well known. This exhibition explores Africa’s position within the Byzantine world’s artistic, cultural, economic, and sociopolitical life.

Africa & Byzantium traces three artistic arcs. From the fourth to the seventh century, early Byzantine visual and intellectual culture was shaped by wealthy patrons, artists, and religious leaders in northern Africa. As Islam became a dominant faith of the region in the mid-eighth century, distinctive Christian religious and artistic traditions nevertheless flourished in African kingdoms. After the Byzantine Empire fell in 1453, Ethiopian and Coptic artists in eastern Africa continued to find inspiration in Roman and Byzantine art through the twentieth century. The exhibition design follows these transformations by evoking and gradually abstracting Byzantine architecture in Africa. The vibrant and inspiring art displayed throughout, culminating with a group of contemporary works, brings alive themes of translation, circulation, and memory, raising critical questions about where and when Byzantium “ends.”

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Africa in Late Antiquity

541. Curtain Fragment with Riders

Andrea Myers Achi, Mary and Michael Jaharis Associate Curator of Byzantine Art

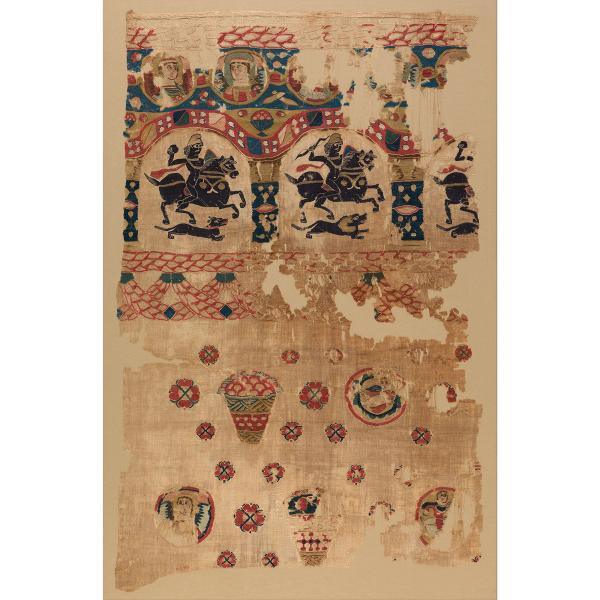

NARRATOR: This approximately fifteen-hundred-year-old cloth owes its preservation to Egypt’s extremely dry climate. Andrea Myers Achi, Mary and Michael Jaharis associate curator of Byzantine art at The Met.

ANDREA ACHI: At the very top are roundels with angels with plump faces, and then beneath that scene you have these riders. They might be military people or people on a hunt, holding rocks and arrows. They appear to be quickly going across the scene, and they have the hunting dogs beneath them. And then at the very bottom you see baskets of fruits, but then also more angels looking in lots of different directions, and then at the bottom right is another rider, and he has this pink and beige cloth rendering.

NARRATOR: Egypt contained many cultures and ethnicities. People came to Egyptian cities from across the Mediterranean, down the Nile from Nubia and beyond, and across the Red Sea from East Africa and India.

ACHI: What’s really interesting to me about this textile is you have people with pink cheeks and beige cloth, but then you also have these black riders. Within scholarship there was this idea that the riders didn’t represent people, and the only people that we see are the beige angels and the rider below. But one thing to consider is the possibility that we're looking at different types of people that were part of communities.

NARRATOR: This textile has lived three lives. First, a skilled fifth-century artisan wove it as a curtain, likely as a commission, to hang in an elite household. Imagine how the weaver’s fingers would have worked the tiny threads of linen and wool on the loom, or how the riders would have danced in the breeze in a doorway. Next, someone wrapped it around a body, beginning its second life as a burial shroud. Finally, The Met received it as a donation from a collector in 1890.

Playlist

“Who now knows,” Saint Augustine of Hippo asked his congregation in Carthage (near modern-day Tunis), “which peoples in the Roman Empire were what, since all have become Romans and all are named Romans?” The year was 416 CE, and Augustine’s question emphasized both the political unity and cultural diversity of the Roman Empire. During the late antique period (around 284 to 641), every major city in the Mediterranean basin, particularly northern African ones, was diverse and multicultural.

For almost 700 years, some of the Roman and Byzantine empires’ wealthiest, most important provinces were in Egypt and northern Africa (now Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco). The region was one of the largest producers of olives and grains, staples in the Mediterranean diet. It was home to dynamic centers of learning and literature, and significant Christian communities developed along the southern Mediterranean basin and down the Nile valley. Kingdoms in Nubia (Sudan) and Aksum (Ethiopia, Eritrea, and parts of Yemen) were also closely connected to Rome and Byzantium, as seen in their art, religion, and culture.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

“Bright as the Sun” Africa after Byzantium

546. Vita Icon of Saint George with Scenes of his Passion and Miracles

Helen Evans, Curator Emerita, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

NARRATOR: This monumental icon is housed in Saint Catherine's Monastery on the Sinai Peninsula, between the Mediterranean and Red Seas. At a location of great significance to people around the world, Saint George, the soldier saint martyred in Syria in the early fourth century, stands with his spear and shield at center. Twenty narrative scenes surround him, including the famous story—at lower left—of him slaying a dragon on a white horse.

Helen Evans is former Mary and Michael Jaharis curator for Byzantine art at The Met, and catalogue contributor and consulting curator for the exhibition.

HELEN EVANS: The holy figure surrounded by scenes from their life, we call them vita icons, life icons, and the suggestion is that you and I would be going to the monastery, and we would be looking at a spot dedicated to Saint George. You would then be told by one of the monks who Saint George was, and he would be able to show you each picture of the miracles that Saint George did, of the various ways that he was tortured.

In the thirteenth century when this was painted the monastery pulled thousands of people, hundreds of people would be visiting at any time. And they would be coming from all over the Christian known world.

NARRATOR: Pilgrims traveled for weeks or months from as far as France and Ethiopia to see Sinai, a place of deep Christian significance. It’s where the prophet Moses spoke to God in the burning bush and received the tablets of the law on the mountaintop. The monks of Saint Catherine’s were accustomed to receiving these pilgrims, regardless of their ethnic or linguistic background.

EVANS: So you get the life of Saint George spoken to you by the monk who can speak Ethiopian or the one who can speak Latin. Today if you go to the monastery, there are different monks who take different pilgrims around according to which languages the monks can speak.

So, it’s important to see it as the famous American phrase; it’s a melting pot.

Playlist

After decades of devastating wars in the seventh century, the Byzantine Empire no longer controlled the southern Mediterranean. Still, Christian communities in northern and eastern Africa remained interconnected, both with Byzantium and across the African continent. By the fifteenth century, Christianity in Africa remained strong. As a witness to this strength, the medieval Ethiopian emperor and author Zärʾa Yaʿǝqob (1399–1468) exclaimed that the faith of his people was “bright as the sun.”

Copts, Nubians, and Ethiopians traveled throughout the Byzantine world. They were guests at the imperial court in Constantinople and spent time in important monastic and pilgrimage centers, such as the Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine at Sinai. The Coptic Church, which had separated from the Byzantine church hierarchy in the fifth century, remained a unifying force across Africa until the early twentieth century. High-ranking members of Egyptian monastic communities were often elected patriarchs of Alexandria, a position that also oversaw Nubian and Ethiopian churches. Echoes of Byzantium remained in the icons, manuscripts, and wall paintings created in northern Africa. The art of northern African Christians retains distinctive characteristics that are still important to the cultural identities of these communities today.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Legacies & Reflections

549. Two Healing Scrolls

Eyob Derillo, independent scholar

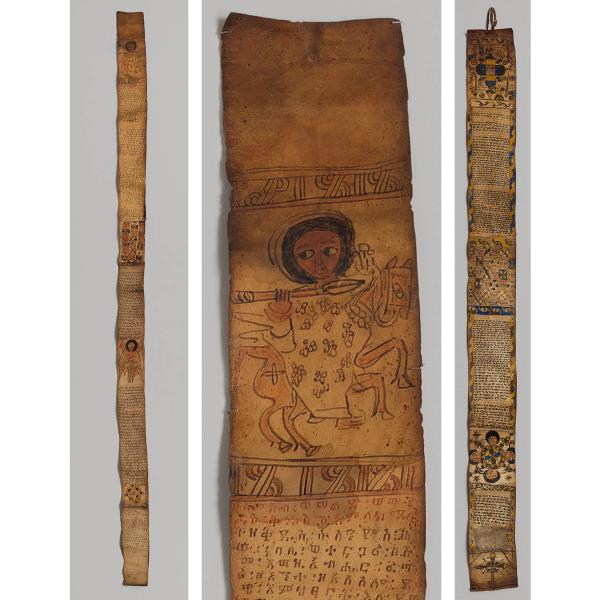

NARRATOR: Ethiopian healing scrolls are traditionally kept rolled up in a case, preserving the potency of their magic and mystery. Unrolled here, they tell a story: of individuals and their deepest needs, of practitioners who call upon spiritual help, of a universal human desire to be protected.

Eyob Derillo, a PhD student in the University of London's School of Oriental and African Studies and catalogue contributor for this exhibition, looks at the very long, narrow scroll with the image of a saint on horseback at the top.

EYOB DERILLO: It’s a prayer for protecting a suckling infant. And it contains the legend of Susenyos. This was a saint who destroyed a demon who was killing children, so judging from the text, this is written for a woman, who was a mother. In a country where there is high rate of infant mortality, obviously you turn to something like this, even nowadays.

NARRATOR: You can see Saint Susenyos on horseback at the top of the scroll. His presence enhances the scroll’s protective power for the person who paid a 'dabtara' to make it.

DERILLO: The word dabtara is somebody who’s highly learned. They’re scribes, they’re highly educated, they practice mathematics, divination, history, law. They are sometimes described as non-ordained priests or clergymen.

NARRATOR: The second scroll here, with its beautiful blue, yellow, and orange ink, contains an incantation for healing epileptic fits. An ailment like this might be treated with traditional medicines and herbs as well as the healing scroll.

DERILLO: There is a universal language, and that’s magic. Wherever you go, from Native Americans to modern new age religion. And the common theme is that amulets exist, elements to protect human beings exist. We use the word incantation, healing scrolls, magic scrolls. But at the end of the day, this item is a physical amulet, a protective element.

Playlist

Byzantium’s legacy in Africa continued after the last emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, died in 1453. Byzantine-style works dating from the sixteenth century to today can help us understand such issues as identity, belonging, and memory among African Christian communities. These sacred objects also illustrate how the convention of dividing artistic developments into distinct “periods” may make less sense than looking at the long-term interactions between the arts of Africa and Byzantium. For example, Ethiopian artists from the early modern period to today continue to translate and adapt new motifs and styles from Byzantine art.

This gallery displays paintings from the small church of Abba Ǝnṭonyos, dedicated to the Egyptian saint Anthony. The church is located in the vicinity of Gondar, the capital city of Ethiopia from the 1630s until the start of the reign of King Tewodros II in 1855. Oral histories of Gondar attribute the construction of Abba Ǝnṭonyos to the patronage of Emperor Yoḥannəs I (John, reigned 1667–82). The wall paintings, manuscripts, and panel paintings in this gallery blend motifs unique to Ethiopian art with themes from Byzantine and medieval Christian art.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.