The Arts of the Ancient Americas

The works in these galleries represent more than six thousand years of visual imagination, cultural meaning, and history. Created in what is mainly Latin America and the Caribbean before 1600 CE, they were commissioned by powerful leaders—kings, queens, and other figures who used art as essential markers of identity, means of belonging, and conduits to the divine.

The names of the artists remain mostly unknown to us—signatures were rare in the Americas before European colonization in the sixteenth century—but their works speak to their achievements in a broad range of media. Many of these artists lived in what were some of the world’s largest cities at the time, under the sponsorship of formidable states and empires. Their creations served, and continue to serve, as bearers of sophisticated knowledge, from complex writing systems to pioneering metalworking technologies.

The ideas and narratives presented in these spaces draw from the transformative scholarship of multiple disciplines—including archaeology, art history, and the study of ancient inscriptions—and from historical and contemporary Indigenous traditions. Here, you will find gold ornaments that catch the sun’s power, stone trees supporting the sky, water materialized in greenstone, and ceramic objects designed for eternal life. These items reveal the connections between regions and the ways in which people and ideas moved and thrived throughout history.

Empires of the Ancient Americas

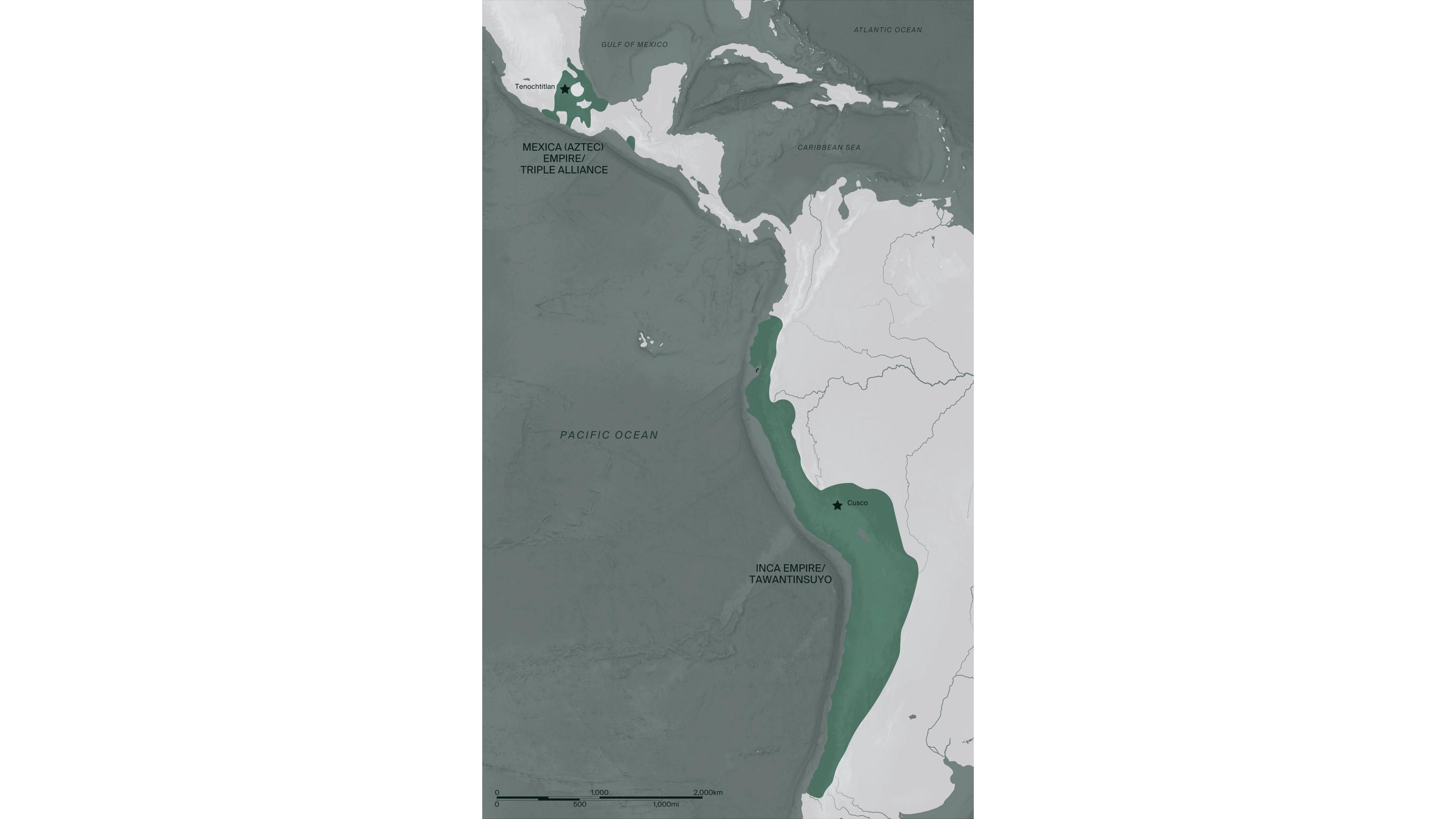

By the time Indigenous Americans encountered Europeans in the late fifteenth century, the two largest empires ever seen in the Americas were at their peak. In the Northern Hemisphere, the Triple Alliance—also known as the Mexica, or Aztec, Empire—dominated a wide swath of Mesoamerica from Tenochtitlan, their capital that now lies under modern-day Mexico City. In the Southern Hemisphere, the Inca controlled much of western South America from Cusco, high in the Andes. These vast empires incorporated independent states, kingdoms, and other communities of diverse origins into their rapidly expanding territories. The Mexica and the Inca, along with the hundreds of coexisting societies, built on the accomplishments of the many cultures that thrived in these regions over the previous fifteen thousand years.

The works of art in these galleries, produced in what is mainly Latin America and the Caribbean before 1600 CE, represent the imagination and achievement of artists in a broad array of media, from delicately carved jade ornaments to finely woven garments. European colonization, wars, and disease caused a demographic collapse in the Americas, but over the centuries Indigenous communities and their artists have proved resilient, at times resisting and at times adapting to shifting global currents.

The boundaries of the Mexica (Aztec) and Inca Empires in the late fifteenth century

Mesoamerica: A Mosaic of Traditions

The region we call Mesoamerica has no precise boundaries; its frontiers have been fluid throughout time. Extending over 350,000 square miles, it covers part of northern Mexico, all of central and southern Mexico, Belize, and Guatemala, and sections of Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. Although it is marked by geographical contrasts—from high-altitude plateaus to humid tropical lowlands, semiarid deserts to coastal floodplains—this diverse region was united through a set of specific cultural practices, including a sacred ballgame and a 260-day ritual calendar.

Over time, civilizations grew from small villages to states and empires—with all communities reliant on a fundamental triad of crops: maize, beans, and squash. Cities were laid out on a central axis and featured pyramidal platforms surmounted by temples. Some ceremonial complexes were further adorned with monumental stone carvings depicting leaders and deities. Rulers served as intermediaries between humans and gods, and offerings (including sacrifice) were necessary to ensure divine favor. Mesoamerican artists availed themselves of precious materials obtained from distant lands, such as greenstone, feathers, gold, shells, and obsidian, transforming them into works of profound cultural significance.

The Ancestral Americas: Deep Time, Diversity, and Endurance

The first settlers arriving in the Americas from Asia embarked on a journey of discovery, unaware of the vast territory that lay before them. Over the next thousands of years, their descendants explored nearly every inch of the hemisphere, giving names to the beings and places they encountered. Animals, plants, mountains, rivers, and forests inspired their cosmology and art; natural materials were transformed into objects of astounding creativity, beauty, and complexity.

The works in this section are testaments to some of the early achievements of these ancient artists: stones carved into refined shapes by North American hunters, delicate animal bones sculpted by fishing communities along the Bering Sea, and clay transformed into durable ceramic female figurines by South American farmers. Over millennia, distinctive Indigenous artistic traditions emerged, flourished, and evolved through the time of the European invasion in the late fifteenth century CE. The impact of colonization and the Americas’ newly global context can be discerned through objects such as the ceramic basin and the stone relief, on view nearby. Despite European domination, Indigenous agency and resilience are evident in the visual arts.

The Maya in the Classic Period (250–900 CE)

Never unified, the Maya region was made up of many competing city-states, sometimes allied, sometimes at war. They occupied a large territory encompassing southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, and western Honduras and shared a common culture organized around the activities of the royal courts—sumptuous centers of artistic production and devotional practices. Maya scribes developed a complex writing system that was both phonetic and pictographic, and used it to record historical and mythical events in books, on buildings, and on portable arts such as vessels and ornaments.

The Maya revered a multitude of gods and goddesses who ruled over aspects of the world. Their dominions ranged from the cycles of day and night to ownership of the earth’s resources, including rain and agricultural bounty. Maya rulers presented themselves as godlike, and they often assumed the aspect of deities in ritual performances. These kings—and sometimes queens—were commemorated in stelae, upright stone monuments sculpted in deep relief that emphasized the sacred nature of kingship in text and image.

Teotihuacan: The Place Where Time Began

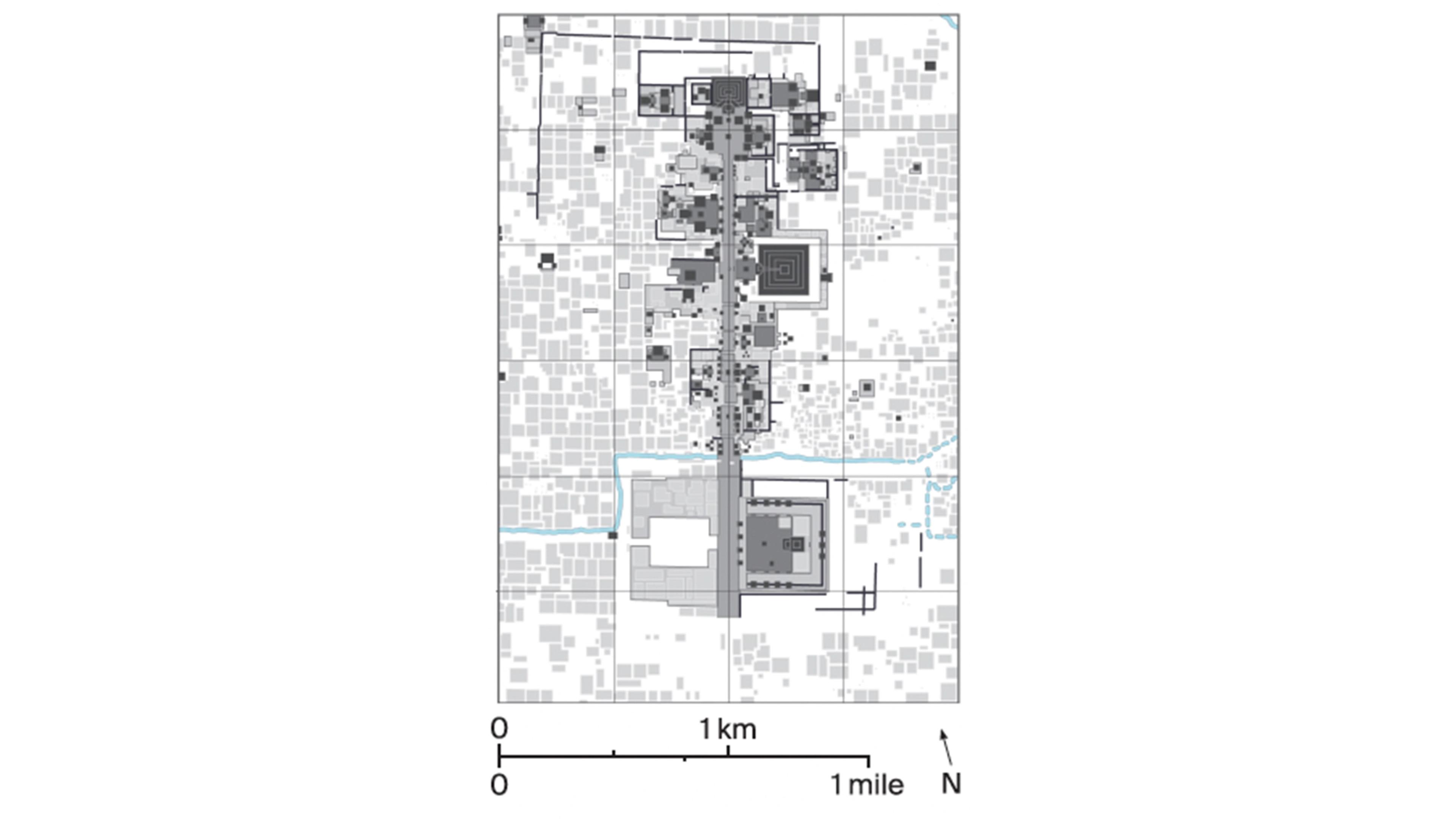

At its height, Teotihuacan (1–650 CE) was one of the world’s largest cities, with a population of up to two hundred thousand. Located on the Mexican Plateau, the urban center was anchored by its civic and ceremonial core. The 1.5-mile-long Avenue of the Dead—oriented north toward the Pyramid of the Moon and the sacred mountain of Cerro Gordo beyond—intersects with an east-west axis based on the solar calendar, creating a grid determined by sacred geography and ritual timekeeping.

The city was artistically vibrant and culturally diverse. The entire population lived in walled residential compounds decorated with colorful murals, while in dedicated workshops artisans created objects in clay, greenstone, and other precious materials. Migrants from across Mesoamerica established barrios, or districts, where craft traditions from their homelands persisted for centuries. The city’s political ties, military strength, and trade routes reached far beyond the Teotihuacan Valley, connecting it to other parts of Mesoamerica.

Looking north along the Avenue of the Dead, toward the Pyramid of the Moon. Cerro Gordo is in the distance. Photograph by Saburo Sugiyama

Teotihuacan’s Enduring Legacy

Teotihuacan’s impact on Mesoamerican culture continued long after the city’s demise in the seventh century ce. For the Mexica who arrived in the region centuries later, Teotihuacan was where the gods set the sun, and time itself, in motion. Much like researchers today, the Mexica strove to understand the urban center’s past and its significance to their own society. To them, the unknown people who built the ancient structures and monuments were godlike and their landmarks sacred, imbued with divine powers. The Mexica extracted treasures from the ruined city and brought them back to their capital. Through this practice, they could claim Teotihuacan’s power for their own.

The center of Teotihuacan, ca. 600 ce. Map by Hillary Olcott after Millon, Drewitt, and Cowgill, 1973

Traditions of the Gulf Coast

Mexico’s Gulf Coast, extending from the slopes of the Tuxtla Mountains in Veracruz to western Tabasco, was a natural corridor for commerce, exchange, and migration. This region became the cultural seedbed that fostered a variety of artistic styles in the Classic and early Postclassic periods (ca. 300–1300 CE). Inheritors of the Olmec tradition and neighbors of the Maya, Gulf Coast artists created works that ranged in scale from the miniature to the monumental.

Along the coast, Huastec carvers worked locally sourced shells to create delicate ornaments that were exported across Mesoamerica. In south-central Veracruz, sculptors excelled in ceramics, forming handheld figurines alongside life-size images of gods and humans. Notably, Gulf Coast artists invented a distinctive type of stone carving closely associated with the ballgame—one of the defining features of Mesoamerican culture.

Living with the Ancestors in West Mexico

Stretching across eight modern Mexican states, West Mexico is known for the lively and distinctive sculptural traditions of the Late Preclassic and Early Classic periods (300 BCE–600 CE). The vast region was home to numerous populations that spoke a variety of languages and maintained different cultural practices and political systems.

Despite this diversity, communities in West Mexico shared similar beliefs about the relationships between the living and their ancestors. A distinctive burial tradition, for example, centered on the construction of elaborate tombs only accessible via long vertical shafts and filled with offerings, including finely made ceramic figures. Some of these works reveal a close observation of the natural world; others emphasize social relations, such as the bonds between family members. These tombs reinforced connections to an ancestral past, bolstering the status of descendants. West Mexican ritual structures also stand apart from others in Mesoamerica; they were often conical in form or arranged in a circular pattern rather than a rectilinear one.

Nevertheless, archaeological evidence demonstrates that West Mexico was closely tied to cultural centers outside the region, such as the great central Mexican city of Teotihuacan. Recent research has underscored the importance of West Mexico in a long-distance trade network with Central and South America, a link that proved crucial for the introduction of metalworking technology into Mesoamerica after 600 CE.

Imperial Mesoamerica

In the centuries before the Spanish invasion of Mexico in 1519 CE, Mesoamerica was dominated by a powerful expansionist state known as the Mexica, or Aztec, Empire. The polity grew stronger through its union of three Nahuatl-speaking city-states in the Central Highlands: Tenochtitlan (the Mexica capital), Texcoco, and Tlacopan. This partnership became known as the Triple Alliance.

The Triple Alliance would go on to forge a loosely organized, but highly successful, empire that extended from what is now Michoacán in western Mexico to as far south as present-day Guatemala, albeit in a somewhat patchwork pattern. Often described as a hegemonic or indirect empire, the Triple Alliance left conquered polities largely unchanged as long as a periodic tribute or tax was paid.

Raw and manufactured goods such as tropical bird feathers, semiprecious stones, gold ornaments, and finely woven cotton garments—along with creative inspiration and expertise—flowed into the capital, prompting a florescence in the visual arts. Mexica artists also drew from the past, emulating earlier styles and producing some of the most spectacular monumental stone carvings known since Olmec times, two thousand years earlier.

Aztlán: Birthplace of the Mexica

The Mexica were the last Nahuatl-speaking group to arrive in the already heavily populated Valley of Mexico around 1325 CE. The Mexica previously called themselves Aztecs after their mythical place of origin: Aztlán (literally, “place of the herons”), an island in a lake. During the migration, their patron god instructed the Mexica to rename themselves. With little land left unoccupied, the Mexica founded their capital, Tenochtitlan, on another lake island. Two centuries later, the once-small settlement had developed into a well-designed urban center with causeways, aqueducts, canals, plazas, markets, and residences for its nearly two hundred thousand inhabitants. Neighborhoods were neatly organized along a grid, the blocks divided by streets and canals.

Reconstruction of Tenochtitlan and its neighboring cities. Image by Tom Filsinger

Ancient Ecuador

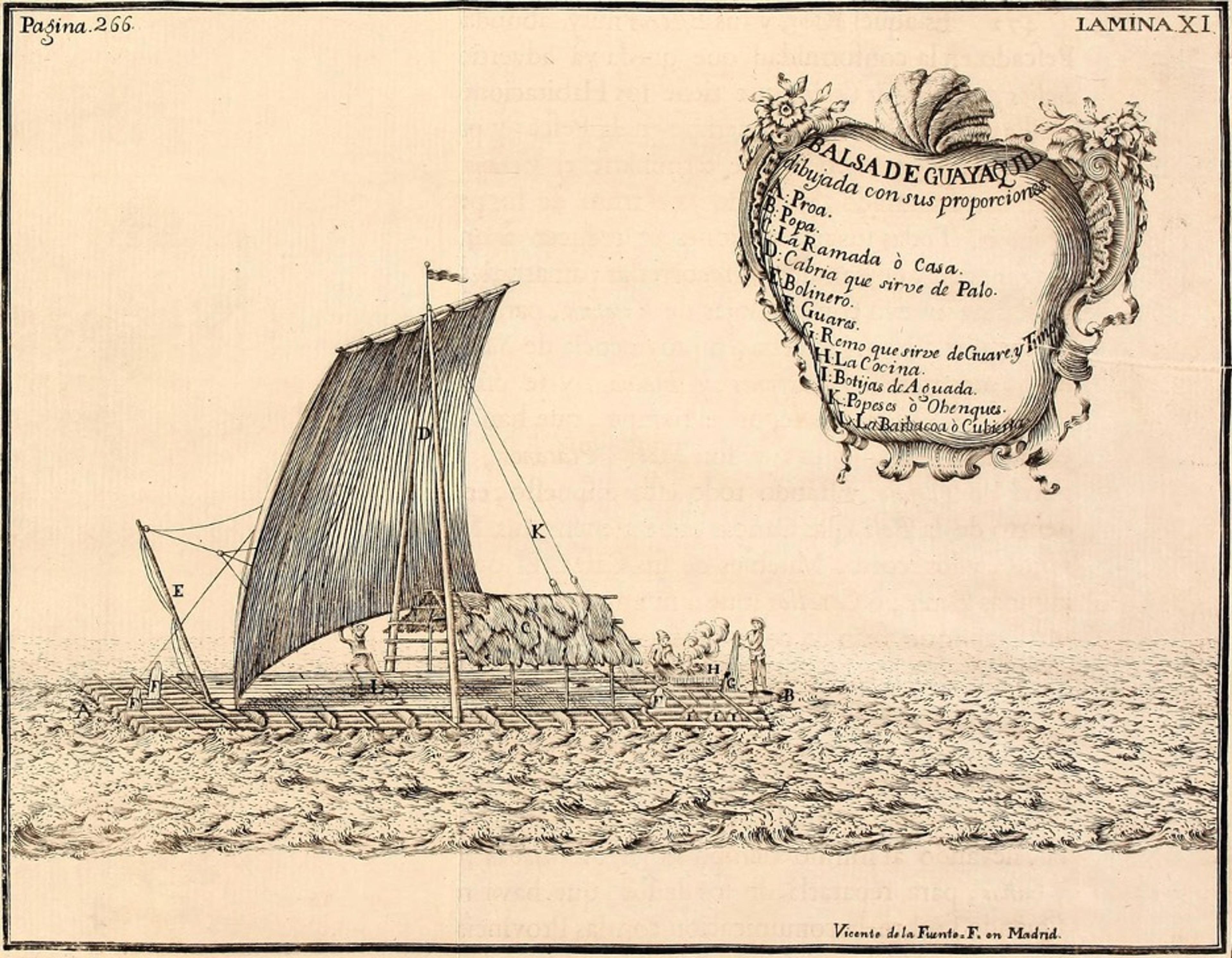

In the sixteenth century, a Spanish ship exploring the northern reaches of the Inca Empire encountered a raft loaded with trade goods—part of an extensive commercial network that spanned from West Mexico to the South Coast of Peru. With its semiarid south, wet north, and populations of prized Spondylus and Strombus mollusks in the Pacific, biodiverse coastal Ecuador connected with other resource-rich areas via land routes into the highlands and the Amazon Rainforest. As these shells were among the most important ritual substances in the Andes, they, together with metal objects, were an important source of coastal communities’ wealth and prestige.

Large settlements in ancient Ecuador were dominated by earthen mounds known as tolas. Structures, perhaps elite residences or temples, were built on top, with tombs set below. The tolas’ elevated placement protected these buildings from floods, but it also separated community leaders from others, visually reinforcing a social hierarchy. Artists often represented these dignitaries, complete with spectacular ornaments that highlighted their religious authority, in different media.

An Indigenous trading vessel. Illustration from Relación histórica del viaje a la América Meridional by Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa, 1748. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library

Ornament in the Northern Andes

The production of finely made gold works and spectacular stone funerary monuments—such as those in the Colombian Andes—marked the emergence of powerful authorities during the first millennium CE. In the sixteenth century, the Spanish called these Northern Andean leaders “caciques,” a term from the Caribbean, now used widely by Indigenous groups, despite the existence of local titles, such as the Tairona term mohanes. Gold ornaments distinguished the leaders’ bodies from others and connected them with a broader elite tradition shared by communities as far as Central America.

Over time, distinctive regional styles developed, with local goldsmiths creating imaginative forms that often defy straightforward interpretation. While most ornaments made from this rare material display evidence that they were worn in life, some were likely made expressly for burials in tombs. After 1000 CE gold was no longer exclusively associated with caciques and was used for additional purposes, including crafting votive objects that were deposited as offerings in caves, lakes, and other revered locations.

A tomb at the San Agustín archaeological site, Alto Magdalena, Colombia. Photograph by Juan Carlos Vargas Ruiz

The Land between the Seas

In antiquity, communities on the Isthmus of Panama, between present-day Colombia and Costa Rica, participated in a dynamic trade network that connected the Caribbean region with the Pacific Coast. These prosperous societies favored an aesthetic of brilliance and iridescence, manifesting in dazzling gold ornaments and highly polished stones.

The northern part of this region was where different value systems converged. The presence of gold reflects the movement of technology and ideas from South America, while the use of greenstone (particularly jade) indicates contact and exchange with Mesoamerican societies. Greenstone was favored in the region’s early history, but after 800 CE gold became the material of choice as it came to embody the authority and power of the region’s leaders.

The Guayabo archaeological site, occupied 900–1300 CE, Turrialba, Costa Rica. Photograph by Kim Richter

The Central Andes

The heartland of the Inca Empire was the Central Andes—today’s Peru, Bolivia, and northern Chile. This territory is defined by the Andes Mountains, which rise more than twenty thousand feet and separate the dry Pacific Coast from the Amazon Rainforest. Before the Inca Empire arose in the fifteenth century CE, hundreds of other societies flourished and faded over the course of millennia. These societies left no written record, but their remarkable achievements in the visual arts remain enduring testaments to their memory.

Our knowledge of these ancient cultures is illuminated through archaeological studies and historical accounts—produced after Europeans introduced writing in the sixteenth century—along with descendant communities’ oral histories and ongoing traditional practices. Often, the civilizations were given new names by scholars, their evolution tracked via changes evident in the most ubiquitous of ancient Andean art forms: the ceramic vessel.

Ancient Andean artists were pioneers in metallurgy, and finely made ornaments of precious metals highlighted the authority of those who wore them. These works conveyed notions of divine status and ultimately became part of an individual’s transformation into a communal ancestor. Vessels and ornaments were fundamental to political negotiation and for communion with a sacred landscape considered both powerful and animate.

A view of the Andes from the Callejón de Huaylas, Ancash region, Peru. Photograph by Hugo C. Ikehara-Tsukayama

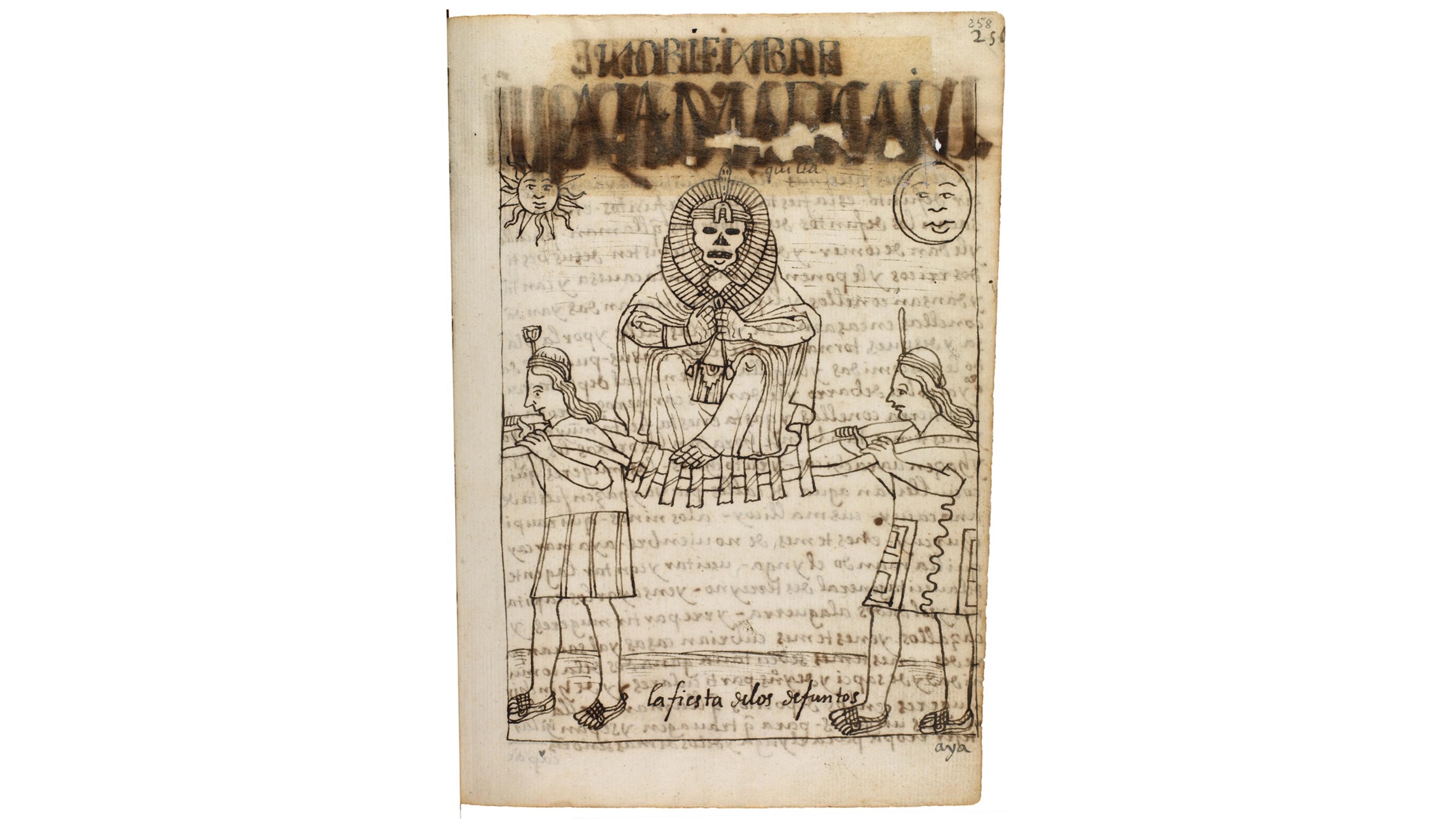

The Beautiful Grandparents

In the ancient Andes, prominent individuals were destined to become ancestors after death. Referred to as “beautiful grandparents” in Quechua societies, ancestors were active agents responsible for a community’s fertility and overall well-being. They were invoked in agricultural rites, marriage ceremonies, and events marking political succession. Death was not perceived as a conclusion; it was part of a continuous existence with both physical and spiritual connotations: a transition from a juicy, soft, and youthful state to one that was drier, harder, and enduring.

To create ancestor bundles, the deceased were shrouded in layers of finely woven garments and often adorned with masks and ornaments. These bundles were carefully maintained in shrines or deposited in subterranean or above-ground structures. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, bundles containing the remains of Inca rulers were brought out on special occasions, continuing a tradition of engagement between ancestors and their descendant communities that began thousands of years earlier.

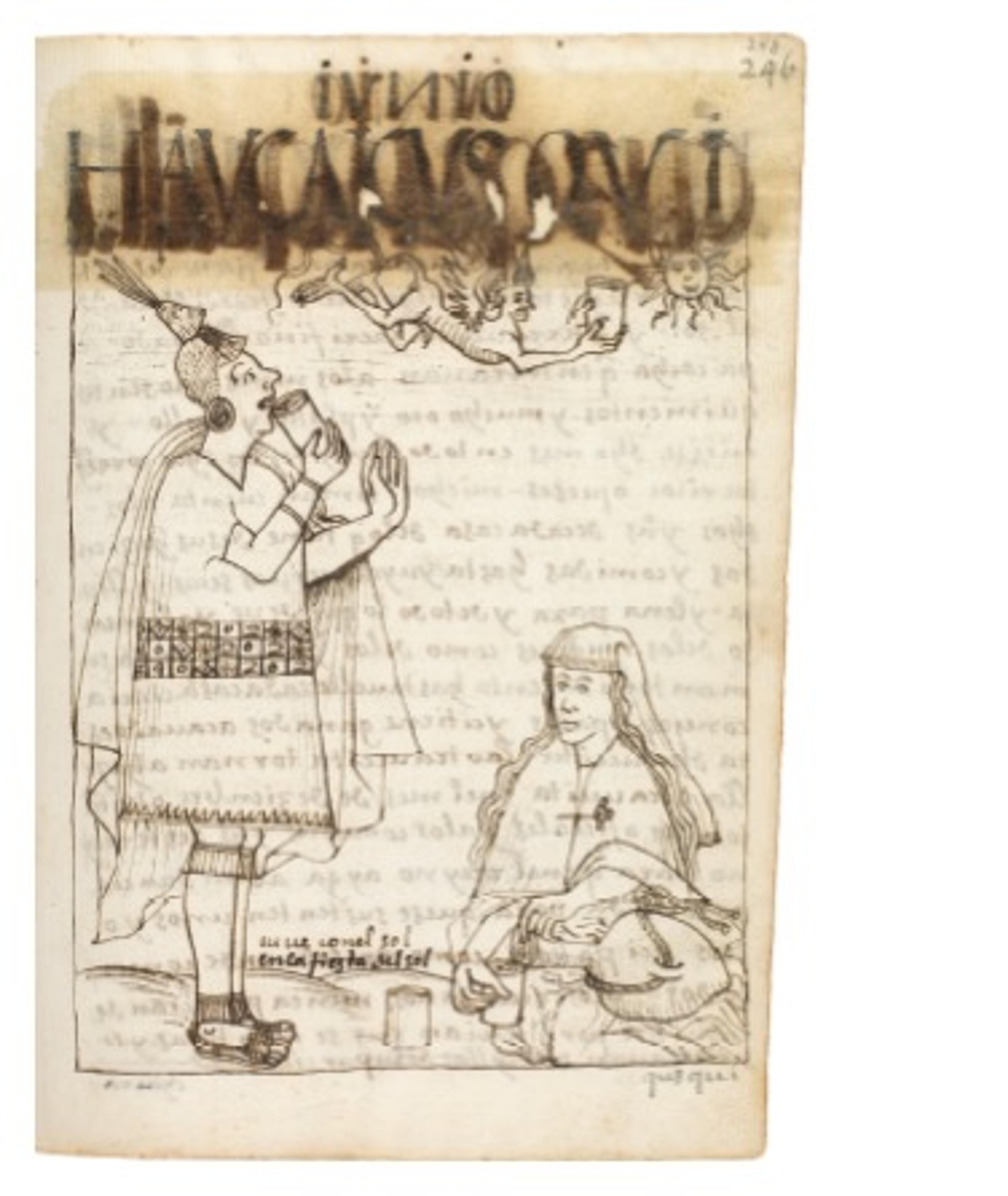

An ancestor bundle in a ceremony celebrating the dead. Illustration from El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno by Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, ca. 1615. Courtesy of Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Copenhagen

Precious Materials

In the ancient Americas, high-status objects were often made of rare materials. Gold and silver captured the imagination of the Spanish, but other natural goods—such as the bright red Spondylus shell—were seen as more valuable by Andean communities. Sometimes acquired from distant sources, precious materials were frequently challenging to work and required the specialized knowledge of skilled artisans. Possession of luxury goods underscored a patron’s control over both valuable resources and expert labor.

Extensive exchange networks for obtaining raw materials became a means by which ideas were shared across regions. Certain metalworking technologies, for example, were first developed in the Andes in South America and later expanded to Central America and Mexico. Across the ancient Americas, artists and their patrons transformed esteemed materials into extraordinary objects, infusing them with religious, social, and political significance. These works cast light on how individuals, collectively or independently, made certain aesthetic and material choices about how to express their deepest beliefs.

Desert Kingdoms

By the end of the first millennium CE, two powerful dynasties arose on Peru’s North Coast: the Lambayeque (also known as Sicán), centered near the modern city of Chiclayo, and the later Chimú, located farther to the south in the Moche Valley. Both built upon earlier Moche artistic traditions but expanded production to a nearly industrial level. The lords of these Northern Dynasties were the patrons of vast workshops for finely crafted ornaments and ceremonial vessels.

The Lambayeque region was conquered by the Chimú around 1375 CE. At its greatest extent, the Chimú Empire dominated some eight hundred miles of the desert coast, from the modern border with Ecuador to just north of Lima. Chan Chan, the Chimú capital and one of the largest cities in the ancient Americas, was organized around ten monumental mud-brick compounds thought to be the palaces of the Chimú kings. Most likely built sequentially by succeeding rulers, the compounds combined administrative, ceremonial, and domestic functions. They ultimately became the funerary monuments of the kings, their descendants, and their retainers. Chan Chan flourished for some five hundred years before it fell to the invading Inca army around 1475 CE.

An aerial view of Chan Chan, Peru, 1931. The large enclosures were the palaces of the Chimú kings. Photograph by Robert Shippee and George R. Johnson, courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History

The Inca and the Art of Empire

As with many imperial powers, the Inca built on earlier aesthetic traditions and technologies. Eschewing the complex iconographies of earlier periods, Inca artists developed a bold new imperial style based on geometric abstraction, evident in works produced in state-sponsored workshops. This unifying style and standardization reflected the extreme control the Inca state exerted over its populace as it rapidly expanded, eventually encompassing most of western South America.

Drinking and serving vessels were a primary focus of aesthetic attention, as feasts were part of an imperial strategy to strengthen social cohesion across the far-flung empire. Containers were also central to rites that celebrated reciprocal obligations between communities and the powerful, animate landscape. Inca emperors offered libations to divinities of the earth and sky, underscoring the rulers’ role as intermediaries ensuring fertility and abundance. Small figurines in the shape of animals and humans—some originally dressed in finely woven textiles—were also created as offerings to be placed on mountain peaks, in lakes, and in other sacred locations in a vital Andean environment.

Inca nobles toast with the sun. Illustration from El primer nueva crónica y buen gobierno by Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, ca. 1615. Courtesy of Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Copenhagen

Weaving Meaning in the Ancient Andes

The Andes Mountains divide the narrow strip of desert along the Pacific Coast from the Amazon Rainforest to the east, with fertile valleys and high-altitude plateaus in between. Their extremely dry conditions resulted in the extraordinary preservation of organic material, including the fabrics and featherwork on view here.

Weaving is one of the oldest and most highly esteemed art forms from the ancient Andes, developing thousands of years before the rise of the Inca Empire (1470–1532 CE). The region also boasts one of the most diverse approaches to textile construction known globally. Drawing on a wide repertoire of geometric and figurative designs, local weavers developed strikingly bold compositions for textiles intended, among other things, for use as everyday objects, royal gifts, and sacred offerings.

Most ancient Andean textiles that have survived are garments or other elements of attire. These are works that were once worn on the body and animated through movement. Large hangings intended to adorn important buildings have also been recovered. These finely crafted fiber works offered unparalleled platforms for ancient Andean communities to express their identities, values, and beliefs.