Introduction

Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840) portrayed nature as a site of emotional and spiritual discovery. Marshaling the expressive power of light, color, atmosphere, and perspective, he created pictures that articulate a profound connection between the landscape and the inner self, or soul. Friedrich’s imagery encapsulates the ideals of Romanticism, an intellectual revolution that championed new understandings of individuality and feeling. His works mark the rise of an intimate response to the natural world that endures today.

Friedrich’s art is grounded in the geography of present-day Germany, which was then a shifting constellation of aristocratic territories rather than a single nation. For four decades, the artist undertook sketching expeditions along the Baltic coast, where he was born, and in the countryside and mountains surrounding Dresden, the city where he made his career. Back in his studio, Friedrich freely reimagined this terrain in compositions that explore the multifaceted meanings of the land during a period of cultural transformation. His works present nature not only as a source of beauty and consolation, but also as a reflection of the aspirations, sorrows, memories, and beliefs that define our personal and collective humanity.

Forging His Path

Friedrich launched his career at the age of twenty-four, in 1798, following several years of training, first in his hometown of Greifswald and then across the Baltic Sea in Denmark. Returning to the German lands and settling in Dresden, the young artist found himself in a vibrant cultural center with spectacular collections and a cohort of dedicated landscape practitioners. Friedrich’s arrival coincided with the circulation of early Romantic ideas about art, nature, and the self.

During his initial years in Dresden, Friedrich searched widely for his creative path. Working as a draftsman and printmaker—he would not make his public debut as an oil painter until 1808—he took on a range of subjects and experimented with different styles and techniques. These works, rooted in his practice of drawing outside and his exposure to Romantic thought, reveal Friedrich’s evolving visualization of the natural world as a site of personal reflection and intense feeling.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Breakthrough

Friedrich made his name as an artist between 1803 and 1808 with ambitious ink-wash drawings, which he submitted to public exhibitions in Dresden and Weimar. These works elicited substantial critical attention for their technical virtuosity and their alignment with the Romantic taste for mood and mystery. Friedrich thus established himself as a major talent in the region’s art scene.

Many of Friedrich’s drawings from this period take their inspiration from the island of Rügen, in the Baltic Sea. In 1801–2, the artist spent significant time on Rügen, recording its distinctive terrain in numerous sketches. These formed the basis for the large, finished drawings he exhibited in the following years. In Friedrich’s hands, the island’s spare, rocky coastline and seemingly endless views of shimmering water and open sky became vehicles for the evocation of solitude, melancholy, and longing.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Nature and Faith

Between 1803 and 1815, the Napoleonic Wars raged across Europe, leaving the German lands battered but their citizens defiantly patriotic. In these years, Friedrich gravitated to emblems of suffering and consolation: Christian crosses, crucifixes, and long-abandoned Catholic monasteries, common to German terrain. He invigorated his subjects with dramatic manipulations of perspective and atmosphere that emphasize the wonder and yearning of a personal journey of belief.

Friedrich’s imagery reflects both his Protestant Lutheran upbringing and the broader Romantic search for spirituality in nature, which was led by radical thinkers such as the philosophers Schelling and Hegel. Is nature “the book of God,” to be experienced and interpreted alongside biblical texts as a source of revelation? Or does divinity reside in the harmonious totality of nature? Friedrich’s portrayal of the landscape as a site of sacred encounter made his art a flash point in culture-wide clashes over religious doctrine and new notions of spiritual life. Decried by some critics as sacrilegious, his works ultimately found receptive patrons and inspired other artists.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Alone Together

Although solitude is an important theme in Friedrich’s art, his creative practice unfolded amid a community of friends and family. The Dresden Academy of Art, where he became a member and later a professor, attracted like-minded peers and pupils with whom he explored the landscape and exchanged ideas and methods. He was especially close to Johan Christian Dahl, a Norwegian-born painter who settled in Dresden. On the home front, Friedrich welcomed his wife, Caroline, and their three children into his studio and involved them closely in his work. The companionship that shaped Friedrich’s art is highlighted in his portrayals of people gazing at nature together.

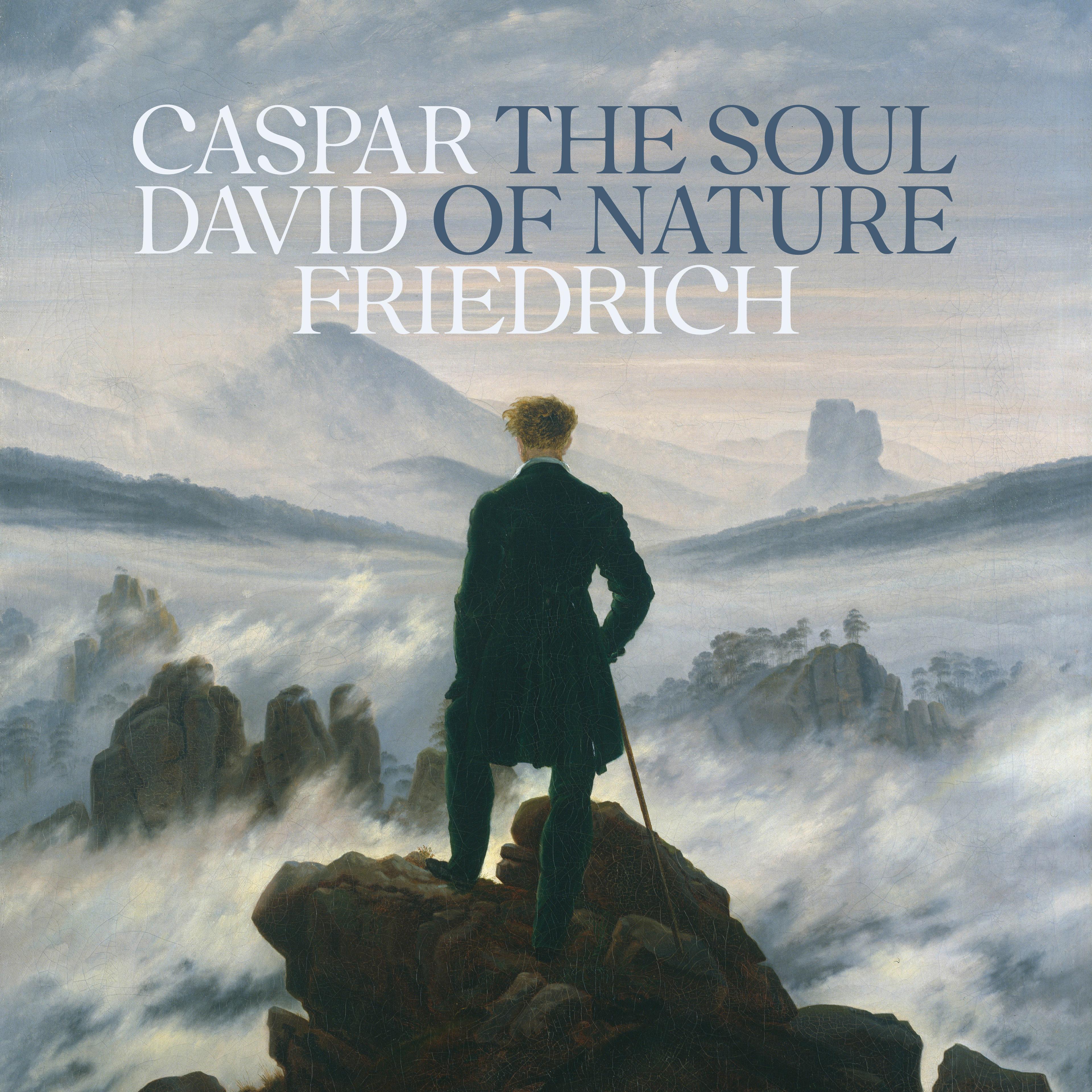

Friedrich’s figures, whether alone or in groups, are often pictured from behind. Artists traditionally employed this motif, called the Rückenfigur (literally, “back-figure”), to prompt viewers’ imaginative engagement with the landscape. Friedrich experimented with the pose and placement of the Rückenfigur, investing it with new import as an embodiment of human connection with the natural world.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Home and Away

In the late 1810s and the 1820s, the overt religious symbols that dominated Friedrich’s early work gave way to imagery imbued with broader spiritual associations. During this period, Friedrich painted numerous scenes inspired by the geography and daily life of places he knew well: the maritime commerce around his birthplace of Greifswald; the landmarks of nearby Neubrandenburg, where his extended family lived; and the skyline and fields of his adopted city of Dresden.

The artist’s seascapes and cityscapes explore the dialogue between familiar, routine existence and distant, unknown realms. As viewers gaze across expanses of earth or water toward prospects on the horizon, they are invited to imagine a journey of self-discovery within nature. Friedrich’s vast skies are amplified by prismatic sunrises and sunsets, radiant moonlight, and spectacular cloud formations, all of which demonstrate his growing confidence with oil paint and his engagement with a vivid, naturalistic style then emerging in Dresden.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Nature's Cycles

Friedrich was repeatedly drawn to the representation of the seasons, which had long served as a metaphor for the cycle of human life. His interest surged in the 1820s, when he produced many treatments of the theme, with a particular focus on winter. These works capture that season’s subtle colors and atmospheric effects and evoke its mingled associations with death and rebirth. Friedrich’s portrayals coincided with a broader Romantic fascination with the emotional resonance of this time of year, encapsulated by Franz Schubert’s 1827 song cycle Winter’s Journey (Winterreise).

Friedrich also meditated on the intersection between nature’s cycles and the rhythms of human history. His images of centuries-old castles and ancient tombs, weathered and overgrown, both memorialize human endeavor and mourn its ephemerality. In the wake of the Napoleonic Wars and the liberation of the German lands, these vestiges of a distant past became emblems of modern political aspirations and disappointments. Following the yearslong conflict, which marked the landscape with yet more ruins, Friedrich and his liberal-leaning compatriots hoped for unity in the form of a German nation grounded in democratic ideals; that dream was crushed by aristocrats dedicated to the old order.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Mist and Mountains

The Romantic era ushered in a new appreciation for mountains as sites of beauty and grandeur. Friedrich experienced dramatic heights firsthand, as an avid hiker, and channeled his perceptions into pictures that responded to the appetite for the sights and sensations of high elevations. His works at midcareer bring a practiced eye to the depiction of rock, capturing its textures and structures from a variety of vantage points, as if documenting it at different stages of a climb. The solid mass of stone is often contrasted with passing clouds and mist, presenting a potent juxtaposition of permanence and transience in an era of new scientific insights into the immense age of the earth. It was precisely the forbidding might of the mountains that appealed to the Romantics; to them, lofty peaks offered an encounter with the sublime—a mixture of beauty, danger, awe, and exultation given iconic form in Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Clarity of Vision

In the late 1820s and early 1830s, public taste shifted away from Friedrich’s introspective, enigmatic landscapes in favor of a more direct manner of representation. Still, the artist remained true to his principles. Critical of the “overly grand execution” of some of his contemporaries, he sought ever greater distillation in his own work. Structuring his compositions around broad swaths of land, water, and sky—crisply rendered but reduced in detail—he imbued his late canvases with dazzling visual rhythms. The clarity of form accentuates Friedrich’s delicate color harmonies, which were informed in part by his watercolor practice.

At this stage of his career, Friedrich expressed his artistic philosophy in writing, explaining his approach to landscape:

"The artist’s task is not the faithful representation of air, water, rocks, and trees, but rather his soul, his sensations should be reflected in them. The task of a work of art is to recognize the spirit of nature and, with one’s whole heart and intention, to saturate oneself with it and absorb it and give it back again in the form of a picture."

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

The Great Beyond

In Friedrich’s final years, his reputation continued to wane and the effects of a stroke made it difficult for him to paint. Yet his creative drive remained undiminished, and he maintained a core of devoted patrons and colleagues in and beyond the German states. Returning to ink wash as his primary artistic vehicle, he dedicated himself to depictions of desolate graveyards, ancient tombs, and empty seashores, subjects that reflect a philosophical interest in death and whatever may lie beyond it. These works, among the last Friedrich made before he died, in 1840, are a poignant capstone to the body of landscapes he had produced over the previous four decades—a visionary evocation of humanity’s complex relationship with the living earth.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.