Introduction

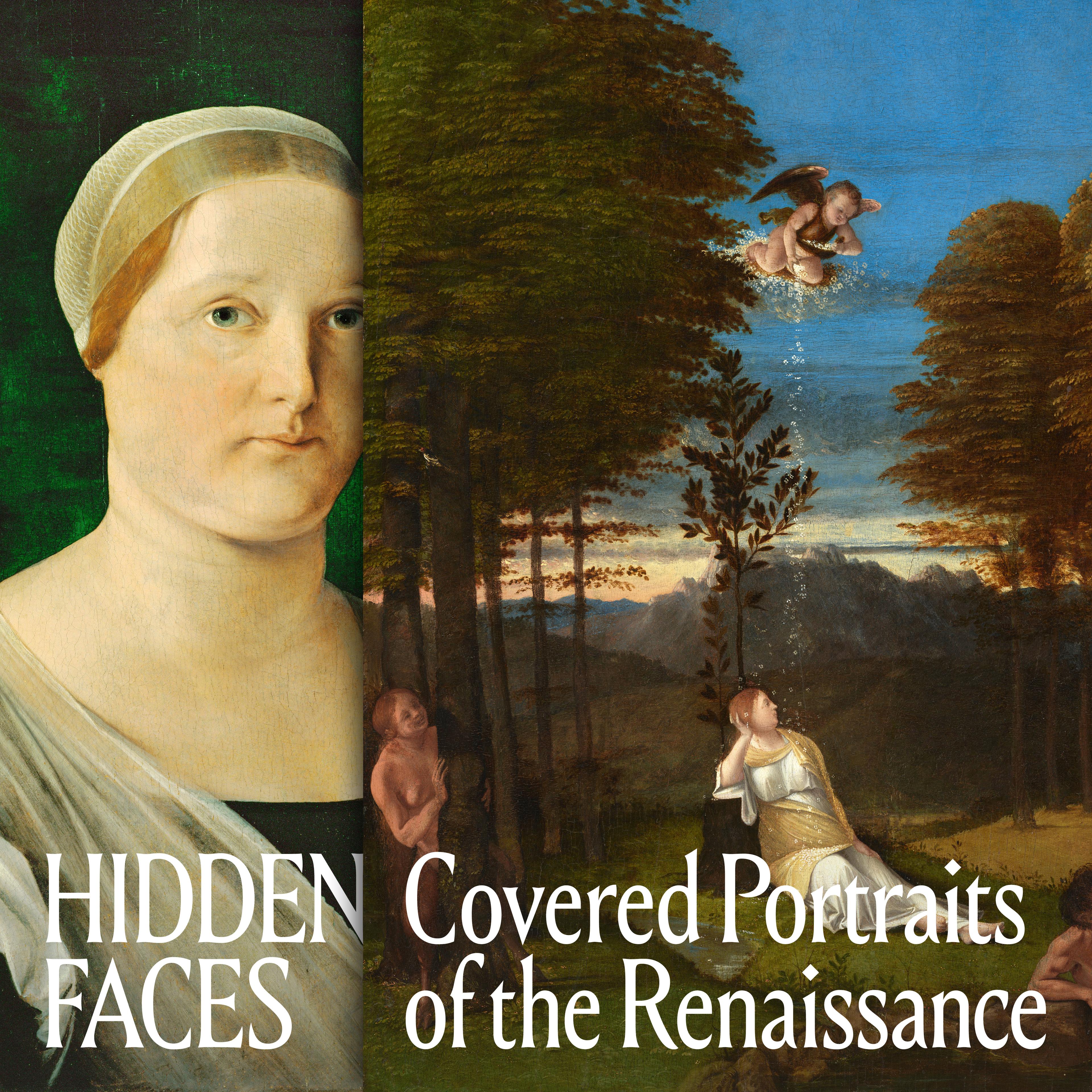

We typically think of painted portraits as two-dimensional works affixed to a wall, unchangeable and permanently visible. However, during the Renaissance, private portraits were often hidden beneath other paintings that served as witty prologues to—and protective covers for—the sitters’ images. These three-dimensional, portable objects included hinged diptychs, double-sided panels that pivoted on a hook and chain, paintings fitted with sliding covers, and boxes and lockets.

The covers and reverses of these ensembles were richly adorned with symbolic imagery and inscriptions that revealed the sitters’ character traits while physically concealing their likenesses below. The viewer was invited to judge the portrait by its cover, decode the enigmatic emblems, allegories, and mythologies, and unmask the persona beneath. Bound in form and meaning, the alternate sides of a portrait shed light on the sitter’s identity and the work’s function as a token of friendship, love, or political allegiance.

While Renaissance inventories attest to the prevalence of multisided portraits, the majority of such works have lost their original frames, covers, and reverse imagery, obscuring evidence of their former structures. Tracing the development of such portraits in Italy and northern Europe during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Hidden Faces acquaints us with the genre’s multifaceted, intimate, and interactive nature.

The exhibition is made possible by the William Randolph Hearst Foundation, the Robert Lehman Foundation, and the Mellon Foundation.

Read, watch, or listen to stories about these works on The Met website.

#MetHiddenFaces

Covering Secular and Sacred Art

Multisided portraits of the Renaissance constitute a rich chapter in a long-standing tradition, stretching from antiquity to the modern age, of concealing works of art. In the sacred realm, such covers range widely in material and format, including shuttered altarpieces, reliquary caskets, and curtains affixed to picture frames or sewn into illuminated manuscripts as well as veils used during the Christian celebration of Lent. The shrouding of a holy object enhanced its sanctity, while its revelation was central to religious practice, activating the image and imparting divine knowledge to the beholder.

Portraits and other types of secular imagery, such as nudes, were often hidden by curtains, covers, and lids, thereby obscuring lovers’ identities and heightening privacy and anticipation. Beyond protection from light, dirt, and other forms of damage, concealment was integral to a portrait’s viewership and meaning, especially when its cover was adorned with coded imagery relating to the sitter.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Covered Portraits in Fifteenth-Century Northern Europe

During the early fifteenth century, bust-length portraits painted with extraordinary naturalism flourished in the Burgundian Netherlands. Similar to double-sided devotional paintings, many of these works by Jan van Eyck and his contemporaries were painted on their frames and reverses with imitation stone, such as marble or porphyry, to highlight the sitters’ status and the endurance of their likenesses for posterity. Later, under Rogier van der Weyden, portraits were also adorned on their reverses with heraldry and personal emblems celebrating the sitters’ identities and dynastic lineages. In the 1470s and 1480s, especially under Hans Memling, the reverses and covers of portraits became the supports for experimental secular imagery. Often alluding to life’s transience, the still lifes, botanical studies, vanitas scenes, and allegories in this gallery represent early examples of these genres, before they became the subjects of paintings in their own right.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Covered Portraits in Italy

Multisided portraits proliferated in Italy toward the end of the fifteenth century, their covers and reverses painted with the same highly inventive allegorical imagery as those produced in northern Europe. Just as stylistic and technical innovations in painting spread north and south of the Alps, so too did an expanding number of portrait structures and the symbolic language that accompanied them.

Beyond Florence, a particularly strong tradition of multisided portraits flourished in Venice under artists such as Jacometto Veneziano, Lorenzo Lotto, and Titian. Ranging from diminutive wood boxes to large-scale canvas covers (a medium employed exclusively around Venice), these ensembles pair the sitters’ physical likenesses with scenes and inscriptions alluding to classical antiquity; personal virtues such as chastity; and the celebration of intellectual, moral, and social standing.

The relationship between covers and the works they concealed was often intentionally enigmatic and intended to prompt discussion among viewers. Lotto, who produced covers for portraits and sacred works throughout his career, vividly expressed this in 1524, advising his patrons that “imagination is needed to bring [a cover’s meaning] to light.”

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Covered Portraits in Sixteenth-Century Northern Europe

The double-sided and covered portraits produced in northern Europe during the first half of the sixteenth century continued many of the traditions established in the preceding decades, with heraldry and allegory remaining the primary forms of the accompanying symbolic imagery.

In addition to the wealthy merchants and bankers in the German cities of Nuremberg, Augsburg, and Frankfurt, the electors of Saxony were significant patrons of multisided portraits that ranged in function from tokens of love to political propaganda.

This gallery presents a unique opportunity to view the reverses of portraits that are not typically exhibited in the round. The backs of the panels bear figurative and heraldic images that once played a significant role in the presentation of sitters but are now partially eclipsed by areas of damage, collection stickers, or cradles (wood slats added in the nineteenth century as structural supports). For these reasons, as well as the complexities of display, the double-sided nature of many portraits remains little known.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Portable Portraits

What I keep, framed in this small pyxis [round box], is the countenance of a golden-haired maiden. . . . I wrote a tearful elegy on her death, and now I treasure this proof of sweet and everlasting remembrance.

—Angelo Decembrio, On Literary Elegance, 1450s

As tokens of friendship, love, or political allegiance, small-scale portraits were frequently given as gifts on the occasion of a betrothal, marriage, or journey. Painted, illuminated, enameled, or carved in wood or wax, these diminutive portraits could be integrated into boxes, gilded lockets, false coins, and watches. Carried or worn on the body, such personal and intimate works were designed for portability and often had cases or bags.

Painted capsule portraits (round images encased in boxes) by German artists such as Lucas Cranach and Hans Holbein paralleled the development of miniature likenesses at the French and English courts beginning in the 1520s. The Protestant reformer Martin Luther capitalized on their transmissible format by commissioning numerous paired roundels of himself and his wife from Cranach. Fitted together in small wood boxes, these were distributed as propaganda upon the couple’s controversial marriage in 1525.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.