If a chess player today were lucky enough to set up a board with pieces from the Lewis hoard, he or she would easily recognize the cast of characters, which became standardized in the Middle Ages. From conversations with visitors to the exhibition, I have learned that some players get tripped up trying to identify the Rooks or trying to distinguish the Kings from the Queens. If asked to play according to medieval rules, however, almost all players today would undoubtedly misstep, as these rules have changed over time and have varied by region. Read on to learn more!

Pawns

The Pawns are the foot soldiers on the "front line" of the chessboard, assembled eight on each side in a horizontal row (or "rank"). Among the Lewis chess pieces, only the Pawns do not assume human form—arguably a sad reflection of the perceived lowly status of the foot soldier. Opposing Pawns from the Lewis hoard are subtly distinguished by shape and, in one case, by a delicately carved pattern that is similar to the belt buckle that was found with the treasure.

Pawns and Belt Buckle, ca. 1150–1200. Scandinavian, probably Norway, found on the Isle of Lewis, Outer Hebrides, Scotland, 1831. Walrus ivory. The British Museum, London (1831,1101.127, .145) © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

The considerable variety in the sizes of the Pawns suggests that the Lewis find may have included more than the four sets that are known to us.

Pawns today follow largely the same rules that they did in the Middle Ages: they advance by moving straight ahead, a single square at a time. In medieval Spain, France, and England, the Pawn could move forward by two squares on its first move, as it can today. A Pawn can only capture another piece diagonally by a single square. The first line of defense and crucial to any attack, the Pawn can also be promoted to a higher rank—and even transformed into an additional Queen—if it reaches the opposite side of the board.

Rooks (also called Castles or Warders)

Warders, ca. 1150–1200. Scandinavian, probably Norway, found on the Isle of Lewis, Outer Hebrides, Scotland, 1831. Walrus ivory. The British Museum, London (1831,1101.122, .124) © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

Each of the Lewis Warders, the equivalent of Rooks or Castles in modern chess, appears as a foot soldier, protected by helmet and shield and armed with a sword. Each has a distinctive shield; their helmets vary, too, one of them looking more like a bowler hat! In keeping with medieval Norse legend, one of the Warders represents a soldier known as a "berserker," a fighter so eager for battle that he contains himself only by biting the top of his shield.

In modern, as in medieval, chess, Rooks are placed at each corner of the King's row, and they can move either up or down or from side to side in straight lines by as many squares as desired. Today, the King and the Rook are also allowed to "castle," which protects the King from capture: in this special maneuver, the King moves laterally by two spaces and the Rook crosses around to the other side of the King to provide extra protection.

Knights

Knights, ca. 1150–1200. Scandinavian, probably Norway, found on the Isle of Lewis, Outer Hebrides, Scotland, 1831. Walrus ivory. The British Museum, London (1831,1101.102, .113) © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

From ancient times, chessboards have included warriors on horseback. Each Lewis Knight, astride his horse, is armed for battle with a spear, sword, protective helmet (with or without ear flaps), and shield (like the Rooks, each shield has individualized decoration). Their steeds are short and have markedly shaggy manes, similar to Icelandic ponies.

Medieval accounts frequently mention that Crusaders en route to the Holy Land entertained themselves by playing chess. It is perhaps not surprising, therefore, that the armor worn by Knights on the chessboard—and sometimes by their horses—is accurately portrayed. On an English chess piece of about 1350–60 in the Metropolitan's collection, knight and horse are protected by mail (the interlocking flexible web of metal chain), while on a later piece the knight's skirt and high shoulder defenses reflect armor of the early sixteenth century:

Chess Piece (Knight), ca. 1510–30. Western European, possibly German or English. Ivory. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Pfeiffer Fund, 1968 (68.95); Chess Piece (Knight), ca. 1510–30. Western European, possibly German or English. Ivory. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Pfeiffer Fund, 1968 (68.183)

One knight of the thirteenth century does battle against a dragon, mimicking the legendary heroism of Saint George; another rides with his falcon, ready for the hunt.

Chess Piece in the Form of Knight, ca. 1250. Probably made in London, England. Walrus ivory. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.231); Chess Piece in the Form of a Knight, ca. 1500. Netherlandish. Elephant ivory. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1984 (1984.214)

In medieval, as in modern, chess, the two Knights stand in the same row as the King, in the second square from the corner. The Knight makes L-shaped moves: he can advance or retreat by two squares and then by one square to either side; alternatively, he can move to either side by two squares ("in rank") and then forward or backward by one ("in file"). The Knight cannot land in a square whose color is the same as the one in which he begins.

Bishops

Bishop, ca. 1150–1200. Scandinavian, probably Norway, found on the Isle of Lewis, Outer Hebrides, Scotland, 1831. Walrus ivory. The British Museum, London (1831,1101.93) © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

Each Bishop from the Lewis hoard wears a mitre on his head and carries a crozier—the long-handled crook used to herd wayward sheep—symbolizing his role as spiritual shepherd of his people. One raises his hand in blessing. Each face of their respective thrones bears a unique pattern, all of which vary slightly from those on the thrones of the Lewis Kings and Queens.

Before the twelfth century, there were no Bishops on chessboards. Instead, there were Elephants, which earned a place in Indian and Persian chess because of their use in war.

Chess piece, bishop, 7th–8th century. Western Islamic Lands. Ivory. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1964(64.262.1)

In medieval Europe, the exotic elephant played no such role. A Bishop might seem equally foreign to the field of battle, but these medieval churchmen served as advisers to rulers and sometimes even raised their own armies. In Trondheim, Norway, where the Lewis chess pieces were likely carved, an archbishopric was established in 1161. Two years later, Archbishop Eysteinn Erlendsson crowned King Magnus V in the cathedral at Trondheim. By their partnership, both church and crown were strengthened against neighboring German rulers.

The carving of a Bishop in the Metropolitan's collection seems to emphasize his spiritual, not political, role. Small figures at either side probably represent men who served in his immediate entourage. The Reader holds his book. As a member of a minor order, he has been "tonsured" by the Bishop—his hair shaved in a circle at the crown of his head. The man holding a staff and cradling his ear may be the Precentor, who was in charge of the choir.

Chess Piece in the Form of a Bishop with Two Attendants, 1150–1200. Made in England. Walrus ivory. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.229)

The Bishops flank the King and Queen on the board. In modern chess, the Bishop can move diagonally forward or backward by as many squares as he wants, as long as the path before him is clear. From the twelfth to the late fifteenth century, his capabilities were different: the Bishop could leap over any occupied adjacent diagonal square.

Queens

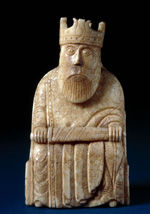

Queen, ca. 1150–1200. Scandinavian, probably Norway, found on the Isle of Lewis, Outer Hebrides, Scotland, 1831. Walrus ivory. The British Museum, London (1831,1101.84) © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

Before the late eleventh century, there were no Queens on chessboards. They gradually replaced the Viziers—close male advisers to the King—that came out of the chess tradition of Islamic Spain. In modern chess, the Queen is the most powerful piece. She can move by as many open squares as she likes, forward and backward, to either side and diagonally. She can capture any piece that stands in her way.

The only medieval chess piece in the form of a Queen in the United States belongs to the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (see image). Initially in medieval chess, the Queen could only move to an adjacent diagonal square. If the Queen were killed, a Pawn could be promoted to her place. However, the thirteenth-century assizes, or rules, of most regions allowed the Queen, on her first move, to leap straight or diagonally to a third square, even if another piece stood in the way.

The Lewis Queens sit on elaborately carved thrones, and their tresses are completely covered by crowns and veils. Each Queen presses her right hand to her face, seemingly anxious. One grasps a horn, the meaning of which is lost to us today. On the field of battle, a horn could signal a call to war or a cry for help; at table, horns were filled with drink. There is yet a third possibility, for a Viking woman's grave discovered on the Isle of Lewis contained a horn full of coins (see image). Could the Lewis Queen, standing by the King, hold a purse that bears the wealth of the kingdom?

Kings

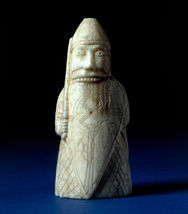

King, ca. 1150–1200. Scandinavian, probably Norway, found on the Isle of Lewis, Outer Hebrides, Scotland, 1831. Walrus ivory. The British Museum, London (1831,1101.78) © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

From the very beginnings of the game, the King has always been the most important piece on the chessboard; they are consequently the largest pieces in a given set. Each of the Lewis Kings holds his sword across his knees and has long hair that falls below his shoulders. One is clearly distinguished from the other by his beard. Their majestic thrones are carved on each face with a distinctive, intricate pattern.

In modern chess, the King may move in any direction but only by one square at a time (except in the special "castle" maneuver with the Rook, discussed above). He may not make a move that puts himself "in check"—that is, at risk of capture. (He also cannot pass through check, in the case of the castle move.) In medieval Europe, the rules for Kings varied over time and according to where the game was played. For example, in thirteenth-century "Lombard chess," the King could leap by up to four squares on his opening move, as long as it did not put him in check.

Recommended further reading: H. J. R. Murray, A History of Chess. Oxford: 1913