As I discussed in last week's post, the first step in the creation of these ivory sculptures was for the artist to establish the conceptual placement of each chess piece within the tusk, allowing for each distinct section of ivory to be cut out. The bottom sides of several chessmen retain the parallel marks of successive saw cuts often interspersed with the less regular cuts of chisels and files used to flatten and refine the base. The underside of the Knight from the Metropolitan, for example, shows the gently arching cut of the saw on the bottom right, chisel marks across the top center, and numerous, parallel cuts that resulted from filing.

Left: Lewis Chessmen, ca. 1150–1200. Scandinavian, probably Norway, found on the Isle of Lewis, Outer Hebrides, Scotland, 1831. Walrus ivory. The British Museum, London (1831,1101.78) © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. Right: Underside of the base of the Chess Piece in the Form of Knight, ca. 1250. English. Walrus ivory. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.231). The base provides a good catalogue of tool marks, including the saw cut on the lower right, a series of chisel cuts across the top, and a variety of roughly parallel striations that appear to be cut by a file. Photograph by Pete Dandridge

Faced with the raw block of ivory, the sculptor would roughly square up the sides and mark out the figure, possibly with lead, but ultimately incising its schematic form across each face with a scribe or awl. One can easily imagine this process with the rather rigid geometric forms of the Lewis Chessmen, but laying out a more complex form like the Metropolitan's Knight would have required more attention.

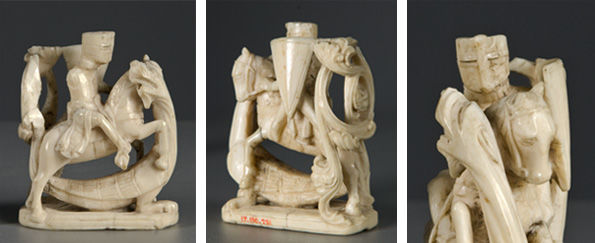

Left: Knight, ca. 1150–1200. Scandinavian, probably Norway, found on the Isle of Lewis, Outer Hebrides, Scotland, 1831. Walrus ivory. The British Museum, London (1831,1101.114) © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. Right: Chess Piece in the Form of Knight, ca. 1250. English. Walrus ivory. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.231)

A variety of tools—including saws, drills, knives, chisels, gouges, gravers, and scorpers—was then available to the artist for the cutting, carving, and finishing of the pieces. Evidence for the use of many of these tools remains visible on the pieces today, allowing us to theorize how each was made.

The most complex of the Lewis pieces are the Knights on horseback, for which large sections of ivory had to be removed in the areas between horse and rider. We can no longer discern the tool marks associated with this step—they were removed during subsequent reworking and finishing—but the most likely candidate is a saw. The utilization of a saw is evident on the Metropolitan's twelfth-century Bishop, where traces of multiple saw cuts are retained along the left side of the throne's base. To create the open space between the legs of the Bishop's throne allowing for the insertion of the saw blade, a single channel/opening would have first been cleared with a drill. Since the space between the figure's back and throne was not accessible to a saw, multiple cuts with an auger opened up the space. A bow drill much like the ones used by Eskimo carvers of the twentieth century probably powered the auger, providing a controlled means of removing large areas of material.

Left and center: Chess Piece in the Form of a Bishop with Two Attendants, 1150–1200. English. Walrus Ivory. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.229). The first image shows the proper right side, the second image shows the piece from above. Three cuts from a saw are visible at the bottom of the opening between the front and back legs of the Bishop's throne. A circular drill cut is apparent in the bottom right of the openwork interlace pattern delineating the throne's arm. A series of drilled holes are visible at the bottom of the excised section of ivory behind the Bishop's back. Under the microscope it is apparent that the holes were made with a spade-shaped auger bit that was common in the medieval period. Photographs by Pete Dandridge. Right: An Eskimo using a bow drill identical to those used in the medieval period to work a walrus tusk, with pressure and stability provided by a chin rest. Photograph courtesy the Alaska State Museum

A drill was also a ready means of integrating negative space into a sculpture. Most of the Lewis Chessmen are solid, but two of the Knights feature spaces between the horses' necks and reins, which were undoubtedly created using an auger.

Knight, ca. 1150–1200. Scandinavian, probably Norway, found on the Isle of Lewis, Outer Hebrides, Scotland, 1831. Walrus ivory. The British Museum, London (1831,1101.102) © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

A very different approach is evident in the carving of the Metropolitan's thirteenth-century Knight, with its dynamic use of negative space to create the openwork vine tendrils and the complex composition of the entwined horse, dragon, and knight. Although direct evidence of an auger is retained only in the opening up of the dragon's mouth, a drill would have been useful in initially clearing many of the open spaces.

The proper right side, proper left side, and a detail from the front of the Chess Piece in the Form of Knight (17.190.231). Photographs by Pete Dandridge

In addition to saws and drills, several types of edged tools were available to ivory carvers for the rough modeling of their forms. The breadth of the cutting edges varied, as did their profiles. Knives, chisels, and gouges were used to remove significant amounts of material from around complex forms and from within confined spaces. The concave facets on the pawn were carved initially with a gouge, while the head or neck of the horse on the Metropolitan's Knight required a broader range of tools.

Left: Pawn, ca. 1150–1200. Scandinavian, probably Norway, found on the Isle of Lewis, Outer Hebrides, Scotland, 1831. Walrus ivory. The British Museum, London (1831,1101.113) © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. Right: Detail of the proper left side of the horse's head from the Chess Piece in the Form of Knight (17.190.231). Photograph by Pete Dandridge

Often, the tooling of more intricate details is only apparent with microscopic examination. Under magnification, one can see that the dragon's wings on the Museum's Knight were made by drawing or pushing a sharp-edged tool along each side of the axis of the line. The cuts creating the V-shaped marks at the ends of the troughs were left by the leading edge of the tool. A miss cut can be seen in the second trough down from the top. The same tool was probably used as a scraper to round off the edges and to create the vertical divisions. The color variation between primary and secondary dentine—which I discussed in last week's post—is also evident at the top of the wing.

Detail of the proper right side of the Chess Piece in the Form of Knight (17.190.231). Photograph by Pete Dandridge

On an early sixteenth-century Knight in the Museum's collection, a flat-edged chisel was adapted to carve the ground beneath the horse. By pivoting the cutting edge of the tool on each corner sequentially, the artist walked the tool across the surface. Each step was accompanied by a gentle strike to cut away a shallow depression, articulating the zigzag pattern.

Chess Piece in the Form of a Knight, ca. 1500. Netherlandish. Elephant ivory. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1984 (1984.214). The photograph on the right shows a detail of the top of the base. Photographs by Pete Dandridge

Subtle elements of modeling and decorative detailing could also be added by gravers and scorpers, which have acute cutting angles that can be sharpened to a variety of shapes, including the more common V and U shapes. Certainly, the geometric pattern on the face of the pawn from the British Museum was cut in with a V-shaped graver, and gravers were used to indicate human hair and horses' manes, details of drapery, and shallow designs on shields and crowns.

Pawn and Rook, ca. 1150–1200. Scandinavian, probably Norway, found on the Isle of Lewis, Outer Hebrides, Scotland, 1831. Walrus ivory. The British Museum, London (1831,1101.127, .121) © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. The fine detail of the incised geometric pattern on the pawn and on the shield of the rook is characteristic of the V-shaped graver.

The complex pattern of the mail on the fourteenth-century Knight in the Metropolitan's collection appears to have been initiated by making a perpendicular and then oblique cut with a gouge for each quarter moon–shaped incision. Each edge of the horizontal channels between the rows of mail were incised with a knife, with the material in between then cut out with a flat-edged graver.

Chess Piece (Knight), ca. 1510–30. Western European, possibly German or English. Ivory. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Pfeiffer Fund, 1968 (68.95). The detail on the right shows the complex pattern of the mail. Photographs by Pete Dandridge

Any of the sharp-edged tools available to the artist could have been tilted and drawn across the surface at a less acute angle to smooth and refine a piece's shape. In fact, evidence of such a scraping action, which leaves a series of parallel ridges along the surface, is found on all of the chessmen. The visibility of the ridges depending on what further finishing or polishing occurred.

Theophilus, the twelfth-century Benedictine monk I mentioned last week, specifically discusses polishing ivory and bone ornaments worked on a lathe with equisetum arvense, or "shave grass"—which, with its high silica content, would have been an effective abrasive—and with wood ash, which would have imparted a higher polish. Subsequent handling, wear, and burial often alter pieces' surfaces, which can make it difficult to confirm the extent of their original finishing.

Detail of the dragon's head and horse's neck and chest from the Chess Piece in the Form of Knight (17.190.231) showing a wide range of surface finishes. Photograph by Pete Dandridge

In cataloguing the technical approaches used to create the chess pieces represented in the exhibition, my colleagues and I found evidence that there was little variation in the kinds of tools employed in the pieces' shaping and modeling. Certainly, as styles changed and the integration of negative space became more common, artists employed more refined saws and augers. Ultimately, however, it is not just technical capacity but also the integration of artistic conception with an intimate knowledge of material that allows for the creation of masterpieces such as the Lewis Chessmen.