We asked Maryam Ekhtiar, our colleague in the Department of Islamic Art, to tell us about the history of chess in Iran, her native land.

Chess is undeniably the most popular board game ever invented, yet its origins are not entirely clear. It appears to have entered Iran through India. This development is documented in a Sasanian text in Middle Persian from the reign of Khusrau I (A.D. 531–579) that recounts the story of its introduction as a contest in refinement and intelligence between the Indians and the Persians. The text mentions that, to prove their prowess, the Indian ruler and his court devised a game (chess) and made a bet that the Iranians could not unravel its logic. The Iranian sage Wuzurgmihr (frequently transcribed as "Buzurjmihr") accepted the challenge and solved not only the mystery but sent back the game of backgammon in return, asking the Indians to do the same. As it turned out, the Indians were unsuccessful, and the Iranians declared themselves the winners. Although the historicity of this story has been questioned, it is the first Persian source to mention the game of chess. Chess and backgammon gradually evolved into princely pastimes and their rules were integrated into training manuals for the edification of princes.

The Persian word for chess, shatranj, was probably derived from the Sanskrit chaturanga, the name of a chesslike game that was played on an eight-by-eight board (modern chaturanga is played on a twelve-by-twelve board). The terminology of modern chess has Persian etymological roots: the Persian word rukh ("rook") means chariot; the term shah mat ("checkmate") means, literally, "the king is frozen"). The poet Firdausi, responsible for versifying the Persian epic poem, the Shahnama, discussed the game and its origins in the epic. He mentions that chess arrived from the land of Hind (India). Illustrated manuscripts of the Shahnama from the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries include paintings showing the envoy from Hind and the Persian counselor Buzurgmihr playing chess. It mentions that chess pieces were made of ivory and teakwood, both of which were easily obtained in India. Curiously, however, no early chess pieces have been unearthed in India.

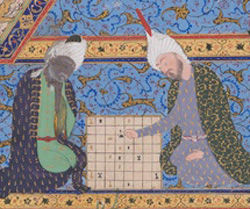

Above: Detail from "Buzurgmihr Masters the Game of Chess", Folio from a Shahnama (Book of Kings), ca. 1300–30. Abu'l Qasim Firdausi (935–1020). Iran or Iraq. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1934 (34.24.1)

Above, left: Detail from "Buzurjmihr Masters the Game of Chess", Folio from a Shahnama (Book of Kings), ca. 1330–40. Abu'l Qasim Firdausi (935–1020). Iran, probably Isfahan. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Monroe C. Gutman, 1974 (1974.290.39); Right: Detail from "Buzurjmihr Masters the Game of Chess", Folio from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp, ca. 1530–35. Abu'l Qasim Firdausi (935–1020). Painter (attributed to): 'Abd al-Vahhab. Iran, Tabriz. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Arthur A. Houghton Jr., 1970 (1970.301.71)

The earliest surviving chess pieces are figural and were excavated at the northeastern Iranian city of Afrasiyab (close to the present-day city of Samarqand) and surrounding areas. An ivory chess piece in the collection is similar in form to the rukhs of that group, representing a man riding a winged beast.

Chess piece, rook or container, 11th–12th century. Iran, possibly Saqqizabad. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Pfeiffer Fund, 1965 (65.53)

A number of the earliest and finest Persian examples were, in fact, excavated in Nishapur, a thriving trading city in Northeastern Iran along the Silk Road, in the 1930s and 40s by the Metropolitan Museum expedition. In 1940, the Museum acquired a number of stylized ivory, alabaster, and ceramic pieces excavated in Nishapur One of these ivories has been colored green (rather than the modern, conventional black) to distinguish it as an opposing piece. One in terracotta is glazed in pale blue.

Above, from left to right: Chess pieces (King, King, Rook, Bishop), 9th–12th century. Iran, Nishapur. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1940 (40.170.150; .151; .148, and .149)

Chess piece, pawn (two views), 9th–12th century. Iran, Nishapur. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1940 (40.170.423)

A highlight of the Metropolitan's collection is a nearly complete chess set (missing only one pawn) attributed to Nishapur and dated to the twelfth century.

Chess set, 12th century. Iran, Nishapur. Stonepaste; molded and glazed. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Pfeiffer Fund, 1971 (1971.193a–ff)

The highly abstracted pieces are made of turquoise and manganese-glazed stonepaste, the forms typical of Persian pieces: the Kings and slightly smaller Viziers (today's Queen) resemble miniature thrones (rather like "slipper chairs"); paired protrusions suggest the tusks of the Elephants (today's Bishop). The Knights are stylized horses. The Rook is a rectangular shape with a V-shaped wedge cut in the top. The Pawns are faceted, with small knobs on the top, similar to those on some of the Lewis Chessmen Pawns. The set documents the continued popularity of chess in Persia and the vibrancy of Nishapur's culture well after its heyday in the eighth, ninth, and tenth centuries, prior to its destruction by a series of deadly earthquakes in the thirteenth century. With haunting prescience of the fate that befell the city, Nishapur's famous philosopher and poet, Omar Khayyám, born in 1048, made chess a metaphor for the mischievous and ultimately deadly hand of Destiny:

'Tis all a Chequer-board of Nights and Days

Where Destiny with Men for Pieces plays:

Hither and thither moves, and mates and slays,

And one by one back in the closet lays.

Further Reading

Daryaee, Touraj. "On the Explanation of Chess and Backgammon" (Persian Text Series of Late Antiquity, 1), Afshar Publishing, 2011.

Wilkinson, Charles, K. "Chess and Chessmen," The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series, Vol. 1, No. 9 (May, 1943), pp. 271–79.

Mackenzie, Colin and Finkel, Irving, Asian Games: The Art of Contest, The Asia Society, 2004.