One of the most interesting things about working on an exhibition is getting to meet all the different people involved on the project. Each member of the team performs a crucial role in preparing for an exhibition. I recently interviewed Kathrin Colburn, a textile conservator here, to find out about her work.

Annie Labatt: Can you tell me what you do here at the Museum?

Kathrin Colburn: I'm a textile conservator, responsible for the Museum's textiles that belong to the Department of Medieval Art and the Cloisters. The collection includes archaeological textiles, ecclesiastical garments, embroideries, and tapestries. My work involves making technical examinations, documenting conditions, performing conservation treatment, installing textiles for exhibitions, and, after an exhibition, preparing textiles for storage. I share my expertise by working with colleagues in the field from different institutions, as well as in conference presentations and professional publications.

Annie Labatt: How did you get interested in textile conservation?

Kathrin Colburn: My interest was sparked by an internship in the Textile Department of the Museum of Applied Arts in Hamburg, Germany, my hometown. During the internship I was involved in a conservation treatment of a European medieval tapestry fragment, and I was captivated by the transformation the fragment underwent during conservation.

Annie Labatt: What was the most challenging or exciting part of working on Byzantium and Islam?

Kathrin Colburn: The last two weeks before the exhibition opened were the most challenging. I spent my time primarily in the galleries, unpacking and checking the condition of the textiles and overseeing their installation. Many of the textiles on display are loans, so they were accompanied to the Met by representatives from their respective institutions; it was inspiring to work with these colleagues. I also enjoyed observing the installation of other objects, from delicate gold jewelry to large-scale mosaics. It was a major undertaking to install an exhibition of such magnitude, and the coordination of different departments was crucial for its success.

Annie Labatt: Did working with these objects or materials change the way you thought of the time period or cultures represented?

Kathrin Colburn: Once I started examining the Museum's textiles that were to be included in the exhibition, I realized how sophisticated they were in terms of materials and techniques. Examining the garments was especially fascinating, with various technical details to be discovered. A row of stitches, for example, could function not only as embellishment, but also as reinforcement in an area that would easily wear down. Even the fragments include technical details that helped me narrow down their original placement in a garment. There are always some unusual pieces—while I could analyze how they were made, I was not always able to tell what they were intended for. There is so much more left to be studied from this time period, which makes working on these textiles so inspiring.

Annie Labatt: Do you have a favorite piece?

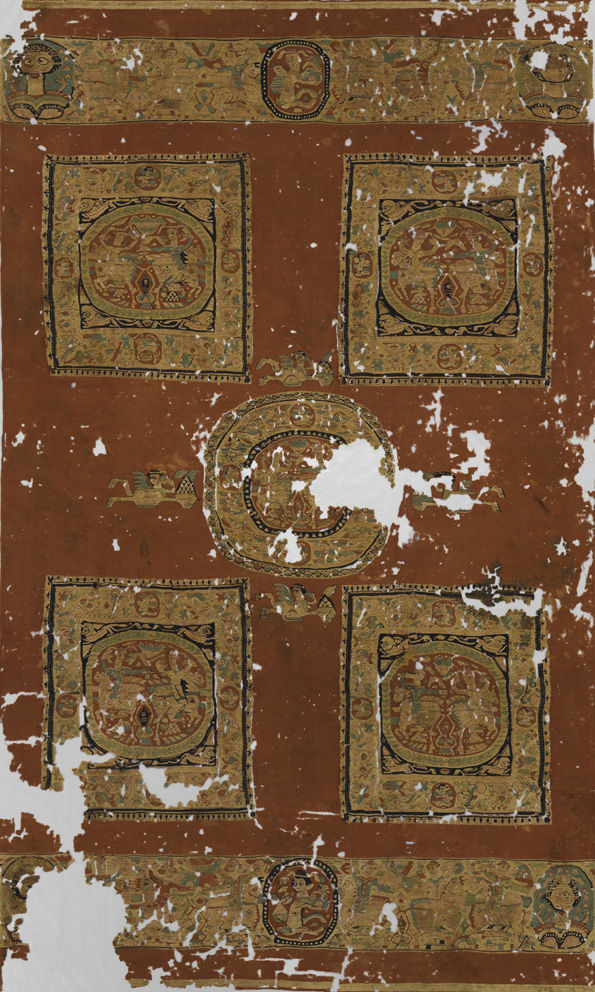

Hanging, 8th century. Egypt. Wool. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Edward S. Harkness, 1929 (29.9.3)

Kathrin Colburn: My favorite piece is a hanging in the first gallery. During research on the exhibition we "rediscovered" it in our storerooms. It has been in the collection since 1929, but there is no record of when it was displayed last. We are delighted to highlight it in this exhibition. I nicknamed it "The Cross-Eyed Lady." Each corner depicts a whimsical portrait of a lady. The background of the hanging is a vivid red with images of abundance woven in shades of blue, green, red, and brown. It was used in a domestic setting as a hanging. Most of the textiles in the exhibition are fragments, while this hanging has survived in its entirety. The conservation treatment on this textile was challenging due to its size and fragility.

Annie Labatt: If you could travel to any of the sites referenced in the show where would that be?

View looking into the south lobe of the sanctuary, ca. 6th–7th century. Red Monastery Church, near Sohag, Egypt. Photograph: Arnaldo Vescovo / © American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE)

Kathrin Colburn: I have been to Egypt once and enjoyed it immensely. Next time I have an opportunity to travel to Egypt, I would like to visit the sanctuary of the Red Monastery Church near Sohag. A film shown in the exhibition highlights its Late Antique wall paintings.

Annie Labatt: If you could have a conversation with any of the historical figures mentioned in the exhibition, who would it be?

Roundel with a Byzantine Emperor, Probably Heraclius, 8th century. Made in Egypt, possibly Panopolis (Akhmim). Tapestry weave in red, pale brown, and blue wools and undyed linen on plain-weave ground of undyed linen. Victoria and Albert Museum, London (T.794-1919)

Kathrin Colburn: I would like to have met the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius. This great statesman and military leader was an imposing figure in the history of Byzantium and his legacy has been depicted in many different art forms throughout history. I am especially intrigued by the gold coins in the exhibition with his simple but striking embossed portrait.