Like Saint Anselm's, which I discussed in an earlier post, Saint Bartholomew's Church in New York City (often known as "St. Bart's") offers an example of early twentieth-century appreciation of the Byzantine aesthetic. In 1918 the St. Bart's congregation moved from its building at Madison Avenue and 44th Street to a grand structure in the Romanesque style on Park Avenue between 50th and 51st Streets. In 1930, Hildreth Meière (American, 1892–1961) designed a series of mosaics for the narthex and the apse.

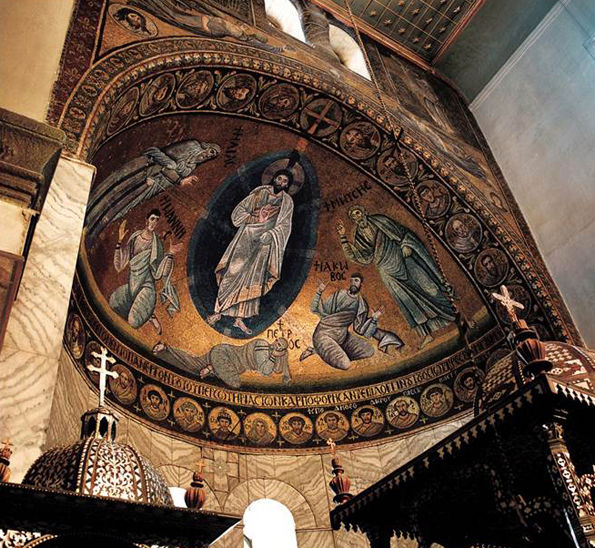

For the apse, Meière chose to depict the scene of the Transfiguration, described in the synoptic gospels as the episode in which Christ, accompanied by the apostles Peter, James, and John, goes to the top of a mountain. There, the apostles witness Christ's transfiguration (or "metamorphosis," in Greek), as well as the appearance of Elijah and Moses, the two Old Testament prophets. Meière's selection of this scene for the apse was a clear reference to the sixth-century mosaic in Saint Catherine's Monastery at Sinai. (Read the related post about the conservation of the Saint Catherine Transfiguration mosaic.)

Transfiguration, Saint Bartholomew's Church, New York.

Transfiguration, Monastery at Saint Catherine's, Sinai, Egypt

In both monuments, Christ stands against a golden background surrounded by a mandorla, or almond-shaped ring of bright colors and rays of light. The vivid rays illustrate the emphasis in the synoptic gospels on the brightness and whiteness of Christ. As the Gospel of Mark says in 9:2–4 (English Standard Version):

And after six days Jesus took with him Peter and James and John, and led them up a high mountain by themselves. And he was transfigured before them, and his clothes became radiant, intensely white, as no one on earth could bleach them.

The Sinai mosaic shows the apostles literally knocked over by the light emanating from Christ. They tumble dramatically and shield their eyes from the wondrous sight. The St. Bart's mosaic shows a different reaction; though no less aware of the central scene, the apostles remain standing. Saint Peter, the apostle standing alone on the left side of the composition, actually resembles Saint Apollinaris as he appears in the mosaic at Sant'Apollinare in Classe, in Ravenna.

Transfiguration, Sant'Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna, Italy. Image: © Wikimedia Commons user Berthold Werner

Like the mosaic in Saint Catherine's, the Sant'Apollinare Transfiguration scene also dates to the time of Justinian (sixth century). In this version, Peter, James, and John are represented as lambs flanking the large gemmed cross. The St. Bart's mosaic echoes the Ravenna scene in its use of trees and verdant landscape. (Coincidentally, or not, Meière used a firm called Ravenna Mosaic Company to produce the glass cubes and to execute her designs.)

The mosaics in the narthex at St. Bart's are similarly spectacular. Each dome represents a different aspect of the Creation story.

Mosaics, Saint Bartholomew's Church, New York

Hildreth Meière's extraordinary work appears in buildings—both secular and religious—throughout New York City. A wonderful recent exhibition at the Museum of Biblical Art told the story of the artist through sketches for many of her most famous commissions, including St. Bart's. It also included her designs for portable works of art, such as altarpieces that could be used by soldiers of many faiths who were sent abroad during World War II.

I'm not sure why the early twentieth-century Episcopalian congregation of St. Bart's chose the Transfiguration scene for their apsidal mosaic. Nor do I know how Merière was inspired by Byzantine and Early Christian mosaics when her only recorded travels abroad appear to have been to Florence. These questions aside, Merière's work, and the monument of St. Bart's, testify to the power of the Byzantine style, the production of mosaics, and the stories borrowed from medieval art.