Silver and gold vessels and architectural elements count among the most dazzling artifacts produced in late antiquity. While Christian, Jewish, and Muslim texts consistently denounce the accumulation of precious metals as reflecting a repellent concern with the trappings of worldly wealth, these traditions also associate gold and silver with heavenly adornment. The Qur'an relates that the blessed in paradise will enjoy vessels in silver and gold, part of the overwhelming visual and sensual experience awaiting those who have left the earthly realm. Silver dishes that have survived from the early Islamic periods offer a glimpse of worldly taste for luxury plates, a tradition inherited from the Sasanian and Roman and Byzantine worlds.

Above, from left to right: Plate with David Anointed by Samuel and Plate with David Slaying a Lion, 629–630. Byzantine. Made in Constantinople. Silver. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.398, .394)

Ewer with dancing females within arcades, ca. 6th–7th century A.D. Iran, Sasanian. Silver, mercury gilding. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. C. Douglas Dillion Gift and Rogers Fund, 1967 (67.10a,b)

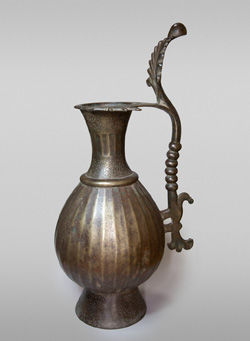

More practical were objects made in baser metals, particularly bronze. Examples survive in a number of forms, including buckets, incense burners, and bowls. Some objects include artists' names, as in a ewer signed by Ibn Yazid. Other examples feature inscriptions listing their owners. Most examples, however, lack such clues, and the variety of types and techniques suggests the existence of multiple production centers over many centuries.

Above, from left to right: Bucket with a Hunting Scene, 6th century. Eastern Mediterranean. Brass, hammered, lathe-turned, chased, and ring-punched. Handle cast separately and hammered into shape. Gift of Frank Steruberg (in 1993). Benaki Museum, Athens. Ewer, 9th century. Iraq or Iran. Bronze, cast. The David Collection, Copenhagen (17/2001)

Ewer, Signed by Ibn Yazid, 688/689 or 783/784 ot 882/883. Iraq. Copper alloy, cast. Georgian National Museum, Tbilisi (w\k I\5)

While the majority of metalwork dating to the early Islamic period has been acquired through the art market, notable examples with archaeological context shed light on function. Fragments of a brazier from al-Fudayn, a site that dates to the Umayyad period, feature figural representations of women, birds, and satyrs. Such a large piece of bronze metalwork undoubtedly served as a luxury object in a courtly setting. Similarly, an incense burner discovered in palatial structures at Umm al-Walid, Jordan, suggests the use of incense outside liturgical settings, perhaps in court ceremonies.

Above, from left to right: Brazier, 8th century (modern reproduction). Jordan. Copper alloy, cast and openwork; iron frame and rods. Jordan Archaeological Museum, Amman (J.15700–J.15707). Lid of an Incense Burner, 8th century. Jordan. Leaded bronze, cast, pierced, and engraved. Madaba Archaeological Museum, Jordan (667)