One of the core themes of the exhibition Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition and its catalogue is the close relationship between commercial activity and cultural exchange.1 The movement of goods and people along trade networks often superseded political impasses between dynasties and empires.

Trade Goods

A dizzying array of goods circulated in the Byzantine and early Islamic Middle East. Best known are prestige objects such as silks, spices, incense, valuable raw materials, and the like, which were closely regulated because of their inherently high material value.2 The widespread taste for luxury silk, for instance, attests to trade networks linking consumers with goods made in faraway production centers. This appears to be the case of the so-called Marwan silk, which may have been made in Central Asia, before being embroidered in the caliphal tiraz factory in the province of Ifriqiyya in North Africa.3

Three Fragments of a Tiraz Inscribed with the Name of the Caliph Marwan, 8th century. Made in Eastern Mediterranean or Central Asia. Weft-faced compound twill weave (samit) in polychrome silk; inscription embroidered in yellow silk in Ifriqiya (modern Tunisia). Victoria and Albert Museum, London (1314-1888, 1385-1888) Victoria and Albert Museum, London, given by the Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester (T.13-1960)

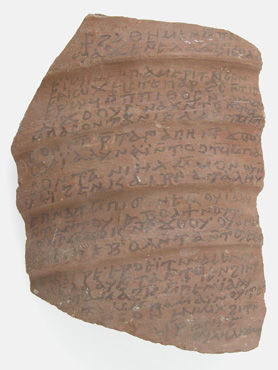

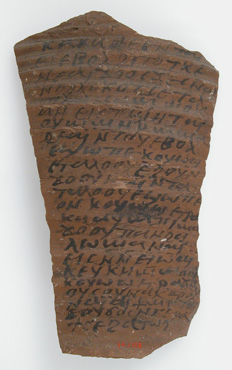

But it is also important to emphasize the quotidian trade goods that circulated on a local level. The production of simple linen textiles, for example, is referenced in ostraka (pottery sherds) from late antique Egypt. Ostraka also frequently mention prices for agricultural products, which is unsurprising in that these formed the foundation of the Byzantine and early Islamic economy.4

Ostraka, 580–640. Coptic. Made in Byzantine Egypt. Pottery fragment with ink inscription. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1914 (14.1.157, 14.1.158)

Tools of the Trade

Beyond the goods themselves, we have a good deal of evidence speaking to the practical mechanisms of commerce in the Byzantine and early Islamic periods. Most valuable are coins, which allow scholars to map out changing patterns in the circulation of money. Numismatists, for instance, study the purity of metal content in coins to understand changes in the overall economy.5 Financial crises can be partially discerned in debased coinage, while differing numbers of coins in hoards can speak to governmental oversight in recalling older issues. Surviving weights give a sense of the tools of commerce used in standardizing measurements, which is especially interesting in that regions often followed different measuring systems.6 Some examples from the early Islamic period even mention the names of local finance officials.

Left: Stamp, vessel, 751–758. Egypt. Glass; Right: Stamp, vessel, 743–749. Egypt. Glass. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1908 (08.256.3, 08.256.7)

Global Routes and Local Markets

Lastly, we might consider the spaces where trade occurred, both along routes and in cities.7 Trade networks in the Byzantine and early Islamic periods can be documented both through archaeological finds and textual sources. The Red Sea, for instance, has emerged as an important corridor for long-distance trade between the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean. Study of these trade routes offers fascinating insight onto the cultural exchanges made possible by the movement of people and goods. The multicultural setting of Mecca at the time of the Prophet is a clear example of the interactions at the intersection of trade networks, pilgrimage routes, and migrations of local tribes.

Similarly important are the urban settings of trade in the form of local markets. In some instances, the early Islamic period witnessed the construction of new marketplaces, as in Baysan (Beth Shean, Scythopolis) in the early Umayyad period.8 In other cities, the transition was more organic. For instance, in Tadmur (Palmyra) in present-day Syria, the stately columns of the city's classical decumanus (main east-west thoroughfare) filled up with ramshackle stalls.9 Whereas "suqs" were once viewed as symptomatic of the decline of the pristine ancient city, they are now understood more positively to reflect the vibrancy of commerce during the transitional period.

[1] See Helen C. Evans, "Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition (7th–9th century)" introduction chapter to Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 4–11, and Thelma K. Thomas, ""Ornaments of Excellence' from 'The Miserable Gains of Commerce': Luxury Art and Byzantine Culture," in Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 124–133.

[2] Thelma K. Thomas, ""Ornaments of Excellence' from 'The Miserable Gains of Commerce': Luxury Art and Byzantine Culture," in Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 124–133.

[3] See catalogue entry 173, "Fragments of the So-Called Marwan Tiraz," in Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 238–241.

[4] Jairus Banaji, Agrarian Change in Late Antiquity: Gold, Labour, and Aristocratic Dominance. (Oxford University Press, USA, 2007).

[5] Stefan Heidemann, "Numismatics," in The Formation of the Islamic World: Sixth to Eleventh Centuries, ed. Chase F. Robinson, vol. 1, The New Cambridge History of Islam (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 648–663.

[6] See Stefan Heidemann, "Weights and Measures from Byzantium and Islam," in Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 144–145.

[7] A good source for these discussions is Marlia Mundell Mango, ed., Byzantine Trade: 4th–12th Centuries (Ashgate, 2009).

[8] Helen C. Evans, "Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition (7th–9th century)" introduction chapter to Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 4–11.

[9] al-As’ad, Khaled and Franciszer M. Stepniowski, "The Umayyad Suq in Palmyra," in Damaszener Mitteilungen, (vol. 4, 1989), 205–223