The historical period explored in Byzantium and Islam was deeply transformative for Judaism. In this post, I'll give a brief summary of Judaism during this transitional time, focusing on some important trends showcased in the exhibition.

During the Byzantine period, Jewish life was centered in the holy land in a mostly rural society oriented around synagogues, which served as places of communal gathering, study, and prayer. The synagogue was considered the most sacred of places and was embellished with symbols linking it to the Jerusalem Temple, such as the menorahs that appear on the Ashkelon chancel screen fragment in the exhibition.

Front and back of a Fragment of a Synagogue Screen with Menorah, 6th–7th century. Made in Israel, found at Ashkelon. Marble. Deutsches Evangelisches Institut für Altertumswissenschaft des Heiligen Landes, Jerusalem (02-001)

Diaspora communities also flourished in places as distant as Rome, Sasanian Persia, and Tunisia, as seen in the Hammam Lif synagogue, which featured rich mosaic decorations in the style of the region alongside traditional symbols such as the menorah.

Mosaic of Menorah and Mosaic of Menorah with Lulav and Ethrog, 6th century. Made in Tunisia, excavated Hammam Lif Synagogue. Brooklyn Museum, New York, Museum Collection Fund (05.27 and 05.26)

Rabbis served as the intellectual and spiritual elite of the community in the holy land and in the diaspora, and the Jerusalem (ca. 4th–5th century) and Babylonian Talmuds (ca. 3rd–6th century), products of the rabbis of Eretz Israel and the Persian Empire, were both codified during this period. There was also a rich proliferation of homiletical (Midrashic) liturgical writings, such as the seventh-century poems of the great Rabbi Yannai.

Palimpsest of the Hebrew Liturgical Poet Yannai over Aquila's Greek Translation of 2 Kings 23:11–27, 5th–6th century; overtext: 9th–10th century. Made in Egypt or Palestine (?), from the Cairo Genizah Medium. Ink on parchment. Cambridge University Library, Taylor-Schechter Genizah Collection, Cambridge (T-S 20.50)

Jews in the holy land often did quite well economically, though they were constantly pressured by Christian authorities—sometimes violently—to convert. Persecutions under the Emperor Heraclius shifted the center of Jewish learning to the communities of the Persian diaspora. When the Muslim armies reached Palestine, some Jews heralded the conquerors as harbingers of the Messiah, and the early Islamic world was generally more stable for Jews, even though as non-Muslims they were placed in a socially inferior position.

During the Islamic period, diaspora communities continued to grow, and Baghdad and Cairo, where most of the Jewish manuscripts in this exhibition were produced, became very important centers of Jewish life. Trade was an important occupation for Jews in these urban centers. Arabic replaced Greek and Aramaic as the spoken language of these Jewish communities, but Hebrew was still used for prayers and for the study of ancient texts.

Bifolium from a Children's Alphabet Primer, 11th–12th century. Blue, red, and yellow ink on parchment. Cambridge University Library, Taylor-Schechter Genizah Collection, Cambridge (T-S K5.13).

Qaraites, a group that coalesced in the ninth century, became a very strong force in the Jewish community in Islamic lands during the ninth and tenth centuries, practicing literalistic interpretation of the scriptures and rejecting rabbinic law.

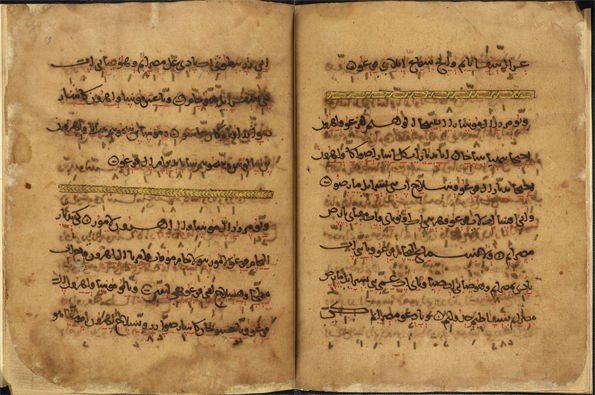

Qaraite Book of Exodus, 1005. Fols. 18v and 19r. Made in Egypt. Ink and pigments on paper; 21 folios. The British Library, London (Or.2540)

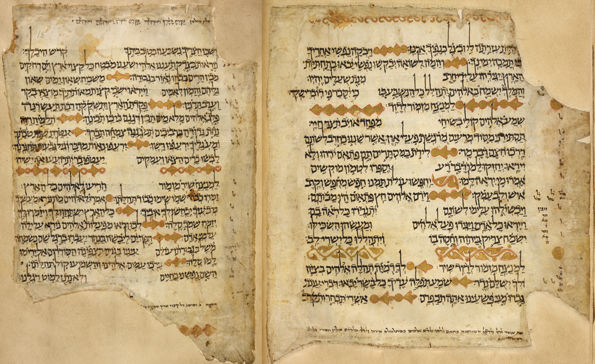

During this period, Jews adopted for the first time the codex form for the Bible. Biblical manuscripts were often written in elaborate calligraphy, with illuminations and textual critical notes, innovations that developed in conversation with Islamic ideas about the importance of the Qur'an text. Several Bibles illustrating this development are part of Byzantium and Islam, including the Gaster Bible, one of the earliest and most ornamented Jewish codices in existence.

First Gaster Bible, 9th–10th century. Made in Egypt or Palestine. Ink and pigments on parchment with gold leaf ornamentation; 40 folios. The British Library, London (Or.9879).

This transformative period witnessed the development of many of the features we consider central to Judaism today. As the world changed around them, Jewish communities adapted to new realities, in deep conversation with their ancient traditions.