Although the Sasanian (Sasanid) empire was centered in Mesopotamia, it played a major role in religious, political, and visual culture in the Byzantine and early Islamic eastern Mediterranean. The dynasty's founding can be traced to Ardashir I (r. 224–241), who established his authority following the defeat of the Parthians. The empire's early years were marked by the emergence of key institutions and cultural developments that would shape Sasanian culture for several centuries. These include complex court ceremonies; diplomatic relationships with Rome and, later, Constantinople; state-sponsored practice of Zoroastrianism; luxury production of silks and silver plate; and the fostering of important Jewish and Christian scholarly centers in Mesopotamia.1 The monumental achievement of the Babylonian Talmud, for instance, was a product of the intellectual flourishing of Sasanian lands in late antiquity.

Sasanians and Byzantines

The Sasanian empire expanded its geographic scope dramatically under Shapur I (r. 241–72), when its lands stretched into Central Asia and stopped just short of the Mediterranean in current-day Syria. This began a centuries-long cycle of expansion and retraction, which placed the Sasanians in direct conflict with Rome, and later, Byzantinum.2 Much of the eastern Mediterranean became a buffer zone between empires, which presented opportunities for rich cultural exchanges in between devastating military battles. Trade and the movement of people resulted in a distinctive frontier culture in towns like Palmyra, Dura Europas, and Resafa that mixed Mediterranean-Roman and Hellenistic-Parthian elements. Dress preferences reflect these contacts. Sculptures from Palmyra, for instance, depict some men wearing pants associated with eastern dress styles, while others don the togas of Roman elites.3

Above, from top: Fragments of a Wall Hanging with Figures in Persian Dress, late 6th–early 7th century. Made in Eastern Mediterranean. Benaki Museum, Athens; Gravestone with Funerary Banquet, ca. 2nd–3rd century A.D. Syria, probably from Palmyra. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, 1902 (02.29.1)

The discovery of Sasanian-style clothing and silk fragments in Egyptian cemeteries further attests to the spreading popularity of these modes of dress throughout the eastern Mediterranean in late antiquity.4

Persian-Style Riding Coat, 443–637. Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin—Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst, Berlin (9695)

On the imperial level, exchanges occurred in Byzantine elites' consumption of Sasanian prestige goods and adoption of ornamental motifs. The courts both mirrored and repelled each other, in an endless game of one-upmanship mediated through diplomatic convoys and reciprocal gifts. The church of Hagios Polyeuktos in Constantinople, built in the sixth century at the height of Byzantine-Sasanian conflict, epitomizes most clearly this dual attitude of appropriation and competition between the powers. It employs distinctly Sasanian motifs in a church commissioned by Anicia Juliana, a powerful member of the Byzantine court and opponent to the emperor Justinian.5 The presence of the ornamental patterns suggests that these motifs were not associated exclusively with a hostile foreign enemy, but carried positive connotations of luxury suitable to sacred space.6

Pillars from the Church of Saint Polyeuktos, Constantinople, now in the Piazzetta di San Marco, Venice. Photograph by spoliast via Flickr

The Tumultuous Seventh Century

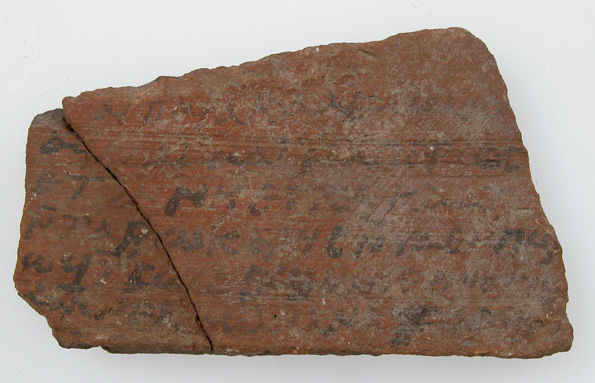

By the seventh century the Sasanians' relationship with Byzantium had turned increasingly antagonistic. The rivalry between the Emperor Heraclius (r. 610–641) and the Sasanian Shah Khusrau II (r. 590–628) was legendary (see Annie's post on Heraclius). Wars between the empires during the early part of the century resulted in the Sasanians gaining control of much of the eastern Mediterranean. An ostraka (pottery sherd) on view in the exhibition details the impact of these invasions on grain supply in Egypt, shedding light on the changes to everyday life that were wrought by the military campaigns.

Ostrakon with a Letter Referring to the Persian Occupation, 618–629. Coptic. Made in Byzantine Egypt. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1914 (14.1.189)

The loss of Jerusalem in 614—along with the city's holy relics, including pieces of the True Cross—dealt the Byzantines a particularly harsh blow. The following decades in the region saw a shift of power between the Byzantines and the retreating Sasanians, before the spread of Islam into Sasanian lands beginning in the 640s. The last Sasanian emperor, Yazdegerd III, died in 651.

Sasanian Legacy in Early Islam

The Sasanian empire had an enduring legacy in the Umayyad period.7 On the one hand, the continuation of certain artistic techniques, such as silk production, plate, and stucco, may be attributed to the caliphs's practical marshaling of Sasanian artists to the service of the new state. There is evidence that the region produced high-quality silks through the early Islamic period, as suggested by the attribution of the so-called Marwan Silk to centers in Central Asia.8

Three Fragments of a Tiraz Inscribed with the Name of the Caliph Marwan, 8th century. Made in Eastern Mediterranean or Central Asia. Weft-faced compound twill weave (samit) in polychrome silk; inscription embroidered in yellow silk in Ifriqiya (modern Tunisia). Victoria and Albert Museum, London (1314-1888, 1385-1888) Victoria and Albert Museum, London, given by the Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester (T.13-1960)

Another area where production seems to have continued was in silver plate, evident in the similarities between late Sasanian and early Islamic examples.

Left: Plate with a Hunting Scene from the Tale of Bahram Gur and Azadeh, ca. 5th century A.D. Sasanian. Iran. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1994 (1994.402); Right: Plate Depicting a Female Figure Riding a Fantastic Winged Beast, probably 8th century. Iran. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1963 (63.186)

Lastly, several Umayyad qusur or "desert palaces" are decorated with motifs like those found in the Sasanian royal residence in Ctesiphon.

Top row: Wall frieze with row of leaves, ca. 6th century A.D. Sasanian. Mesopotamia, Ctesiphon. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1932 (32.150.10); Bottom row, from left: Panel, ca. 6th century A.D. Sasanian. Mesopotamia, Ctesiphon. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1932 (32.150.5–.8); Block Carved with Acanthus and Palmette, ca. 720–724. Made in Jordan, Qasr al-Qastal. Department of Antiquities, Qasr al-Qastal Archaeological Site, Jordan

On a more symbolic level, however, the Umayyad dynasty drew from Sasanian motifs in the development of their own distinctive visual culture. The mosaics of the Dome of the Rock commissioned by Abd al-Malik in about 691/2 deploy winged vegetal motifs reminiscent of Sasanian imagery. The semi-nude female figures in the stuccos at Khirbat al-Mafjar call to mind a Sasanian silver vessel with dancing women, again suggesting continuities with the older visual culture.

Left: Statue of a Woman, from Khirbat al-Mafjar, Jordan, mid-8th century A.D. The Rockefeller Museum, Jerusalem (M. Hattstein and P. Delius, Islam: Art and Architecture, p. 83). Right: Ewer with dancing females within arcades, ca. 6th–7th century A.D. Iran, Sasanian. Silver, mercury gilding. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. C. Douglas Dillion Gift and Rogers Fund, 1967 (67.10a,b)

More concretely, the production of Sasanian-style dirhams well into the Islamic period—eventually with Arabic additions— demonstrates the Umayyads' efforts to express their legitimacy through the appropriation of older visual systems.

Obverse (left) and reverse (right) of a Dirham of Sasanian Type, 693/694. Made in Damascus. The American Numismatic Society, New York (1971.316.35)

[1] For a discussion of developments in the arts of the period see Prudence O. Harper, The Royal Hunter: Art of the Sasanian Empire (New York, 1978).

[2] See Alexander Nagel, "Sasanian Expansion to the Mediterranean," in Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 27.

[3] Bernard Goldman, "Graeco-Roman Dress in Syro-Mesopotamia," in Judith Lynn Sebesta and Larissa Bonfante, eds., The World of Roman Costume (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2001), 163–181.

[4] Cäcilia Fluck, "Dress Styles from Syria to Libya," in Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 160–161.

[5] Martin Harrison, A Temple for Byzantium: The Discovery and Excavation of Anicia Juliana's Palace-Church in Istanbul (Harvey Miller, 1989).

[6] As discussed in Matthew Canepa, "The Late Antique Kosmos of Power," in The Two Eyes of the Earth: Art and Ritual of Kingship between Rome and Sasanian Iran. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010, 188–223.

[7] A foundational text discussing these issues is Richard Ettinghausen, From Byzantium to Sasanian Iran and the Islamic World: Three Modes of Artistic Influence. Leiden: Brill, 1972.

[8] See catalogue entry 173, "Fragments of the So-Called Marwan Tiraz," in Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 238–241.