Charles M. Russell (American, 1864–1926). Indian Braves, 1899. Watercolor on paper, 20 7/8 x 29 3/8 in. (53 x 74.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Thorne E. Lloyd, 1970 (1970.286)

In the mid-nineteenth century, the American West was a popular subject for artists working in a variety of media, from painters and illustrators to photographers and printmakers. At that time, images of western buttes and bison, cowboys and American Indians were widely disseminated by the popular press, captivating national and international audiences. These works familiarized the public with the facts and fictions of the West, helping to lay the foundation for the flourishing of western-themed bronze sculpture at the turn of the twentieth century.

American Indians by American Artists: Works on Paper from the Collection is currently on view in Gallery 773 in the Museum's Henry R. Luce Center for the Study of American Art. Expanding upon one of the four main themes of The American West in Bronze, 1850–1925, the installation takes a closer look at representations of American Indians by American-born and foreign-born artists working in the United States between 1805 and 1928. It features twenty works on paper from the Museum's collections, including watercolors, graphite drawings, sketchbook pages, printed books, and ephemera (such as advertising posters and collectible cards sold in cigarette packs). I spoke recently with Jessica Murphy, research associate in The American Wing, who organized the installation. "We wanted to include a sampling of media," Jessica said. "While many of the works are unique renderings, often intended for private ownership, others were created as multiples for mass reproduction and middle-class consumption."

Organized chronologically, the installation traces how the theme of the American Indian recurrently captured the imagination of artists. "By the early twentieth century, artists' interest in the American Indian had not waned; if anything, it had increased with time," Jessica explained. "These artists were very much aware of their subjects' changing place in American life, as Euro-American settlers pushed westward and Indian nations were relocated onto government-established reservation lands." From the early watercolor portraits of Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin—a French artist working in the United States from 1803 to 1810—to the commercial posters of Lafayette Maynard Dixon—an American illustrator working for the San Francisco–based magazine Overland Monthly in the 1890s—the show reveals the lasting and widespread attraction to this readily identifiable American subject.

Featuring portraits, narrative scenes, and depictions of American Indians in the landscape, the installation highlights little-known works by familiar artists, including Thomas Cole and Emanuel Leutze (who are perhaps best known to visitors of The American Wing for their iconic paintings The Oxbow and Washington Crossing the Delaware, respectively). Also on display are watercolors and drawings by several of the sculptors included in The American West in Bronze, such as Henry Kirke Brown, John Quincy Adams Ward, and Charles M. Russell, whose Indian Braves (above) was recently restored.

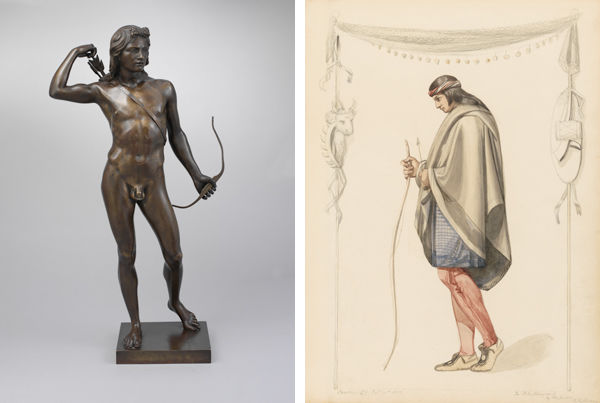

Left: Henry Kirke Brown (American, 1814–1886). Choosing of the Arrow, 1849. Bronze, 22 x 11 3/8 x 5 5/8 in. (55.9 x 28.9 x 14.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Mia R. Taradash and Dorothy Schwartz Gifts, and Morris K. Jesup and Rogers Funds, 2005 (2005.405a–d); Right: Henry Kirke Brown (American, 1814–1886). Indian Figure in Profile, 1851. Watercolor and graphite on thin off-white gilt-edged Bristol board, 14 1/8 x 10 7/16 in. (35.9 x 26.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Morris K. Jesup Fund, 1989 (1990.46.2)

When I visited American Indians by American Artists, I found it particularly rewarding to compare works from this show with the sculptural representations of American Indians I had seen in The American West in Bronze. I was particularly drawn to Henry Kirke Brown's Indian Figure in Profile, a watercolor and graphite drawing that dramatically contrasts with his bronze Choosing of the Arrow. Both works were inspired by Brown's 1848 trip to Mackinac Island in Lake Huron, Michigan, during which he sketched and painted members of the Chippewa and Ottawa tribes. In Choosing of the Arrow, Brown depicted an elegant, idealized male nude standing in contrapposto pose, a clear quotation of the classical sculptures he had studied while in Italy. In contrast, Indian Figure in Profile presents a fully clothed man, whose faithfully delineated garb and dignified demeanor reflect the artist's careful observation of his subject. As in the bronze, this figure is equipped with a bow and arrow, yet Brown also included details alluding to hunting and fishing, such as the shield, spear, rifle, and bison head that decorate the posts of the fishnet canopy draped overhead. Interestingly, both of these works contrast with Brown's written descriptions of American Indians he encountered during his trip, who he described in an 1848 letter to his wife as "degraded." The artist nevertheless maintained his "reverence [for] the independence and freedom of their minds," as he wrote in 1848, creating noble images of his subjects that combined imagination and observation.

The differences between Brown's two- and three-dimensional representations of American Indians may reflect the intended audience for each work. The American Art-Union commissioned and distributed twenty casts of Choosing of the Arrow, and for this audience Brown crafted a heroic vision of life in the West before Euro-American settlement. Indian Figure in Profile, however, was produced in 1851 for his friend and patron Henry Gurdon Marquand, with whom he had traveled to Mackinac Island in 1848. This watercolor was intended to commemorate their trip and closely resembles one of the firsthand sketches the artist executed from life while in Michigan.

Americans Indians by American Artists is on display through April 13, 2014. I encourage you to make your own comparisons and share your observations here, as these artworks speak to each other (and to us) in varying ways.