William S. Hart as Two Gun Bill, from The Gunfighter, 1916. Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

In a 1967 interview, director Anthony Mann described the Western as "legend—and legend makes the very best cinema…It releases you from inhibitions, rules…you can ride the plains; you can capture the windswept skies; you can release your audiences and take them out to places which they never would have dreamt of." This sense of freedom and adventure, often combined with a deep appreciation for the natural landscape, characterizes many great American Westerns, from the early silent era "oaters" of D.W. Griffith to the psychologically complex portrayals of the Westerner by American icons such as John Wayne and Clint Eastwood. At the same time, many Westerns combine the magic of myth with the pretense of having captured the gritty authenticity of historical reality.

I recently spoke with film scholar Kevin Stoehr, who co-authored Ride, Boldly Ride (2012), the first comprehensive survey of the American Western, a cinematic genre as old as filmmaking itself. "The Western began with the birth of cinema in the 1890s," Kevin explained. "Thomas Edison, using early cinema technology, filmed reenactments from Buffalo Bill's Wild West show, including Annie Oakley enacting a sharp-shooting demonstration, a cowboy riding a bucking bronco, and a Native American buffalo dance. These short films should be considered as the earliest precursors of the American Western movie." The first two films are on view in the Met's installation of The American West in Bronze, 1850–1925 (and all three films can be viewed on the National Film Preservation Foundation's website).

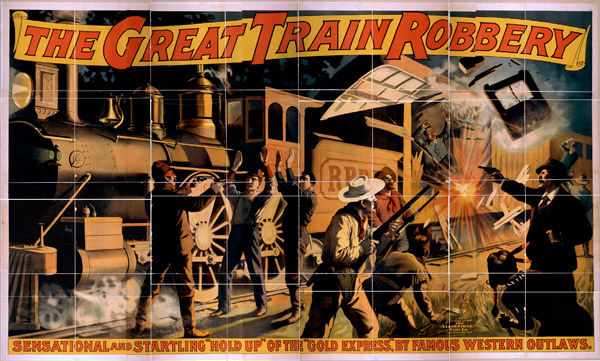

The Strobridge Lithographing Company. Movie poster for The Great Train Robbery, ca. 1903. Color lithograph; 9 ft. 2 5/8 in. x 15 ft. 6 1/4 in. (281 x 473 cm). Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Within a decade of Edison's early documentaries, Edwin S. Porter directed the first feature Western, The Great Train Robbery (1903). Eleven minutes in length, this film tells the story of a violent robbery aboard a moving train. "This is one of the first Westerns to tell a unified story with a dramatic climax and to incorporate special effects in the service of visual spectacle," Kevin said. Intercutting studio shots with matte shots of the passing landscape, Porter created the illusion of a moving train. The film ends with an iconic shot of a gunman firing his pistol directly at the audience, and the color-tinted gun smoke added to the film's popular appeal.

While many early Westerns, including The Great Train Robbery, were shot in New York and New Jersey, by 1910 filmmakers were traveling out west to take advantage of warmer climes. D.W. Griffith was one of the first directors to film in Southern California, where he shot his Western melodrama Was He a Coward? (1911). Incorporating elements of romance and comedy, the film chronicles the challenges of an Easterner turned ranch hand. This "tenderfoot" (played by Wilfred Lucas) moves out west to recover from a nervous breakdown and falls in love with a rancher's daughter (played by Blanche Sweet). "The comedy comes from the difficulties this Easterner faces as he adjusts to the rough reality of frontier life," Kevin explained. "This is an archetypal Western comedy and it features a character that was later popularized by actors such as Douglas Fairbanks and Bob Hope."

The Great Train Robbery and Was He a Coward? will be shown in an afternoon of silent film classics hosted by Kevin Stoehr at the Met on Saturday, February 1, from 2:00 to 4:00 p.m. Kevin will also screen excerpts from Hell's Hinges (1916) starring actor William S. Hart as cowboy hero Blaze Tracy. Blaze begins the film as a morally ambiguous character, but he is transformed into a virtuous hero after falling in love with a preacher's daughter, Faith (played by Clara Williams). In the following clip, Blaze exacts revenge upon a saloon of outlaws responsible for corrupting the preacher and burning down the town's church.

William S. Hart in Hell's Hinges (1916). Preserved by The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Kevin describes Hart as "a stoic, quiet, laconic Western star. In many respects, he is the precursor to Western performers such as Henry Fonda, Randolph Scott, and Clint Eastwood." The iconic pose adopted by Hart in this clip and in the above film still from The Gunfighter (1916) earned him the nickname "Two Gun Bill." Sculptor Charles Cristadoro immortalized the actor in this pose in his 1917 bronze sculpture Two Gun Bill (William S. Hart), currently on display in The American West in Bronze, 1850–1925.

Charles Cristadoro (American, 1881–1967). Two Gun Bill (William S. Hart), 1917 (cast 1925 or after). Bronze; 37 7/8 x 12 x 19 in. (96.2 x 30.5 x 48.3 cm). Autry National Center of the American West, Los Angeles (88.379.1)

Other American sculptors who depicted Western film stars included Charles M. Russell and Sally James Farnham, who both created bronze statuettes of actor Will Rogers. Many American directors also looked to painted and sculpted visualizations of the West as sources of inspiration for their films. John Ford, for example, often tried to imitate cinematically the colorful landscape paintings of Frederic Remington, Charles M. Russell, and Charles Schreyvogel.

Kevin will discuss the relationship between Western art and film in his lecture "The Artistry and Evolution of the Hollywood Western Movie" at the Met on Sunday, February 2, as part of the Museum's Sunday at the Met lecture series. He will be joined by The American West in Bronze, 1850–1925 co-curator Thayer Tolles, who will introduce the program, as well as Peter Hassrick, director emeritus and senior scholar at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, who will give a lecture entitled "An Evolving Icon: The Cowboy in Bronze." The program will conclude with a demonstration by the Federation of Black Cowboys.

Both the film program and the Sunday at the Met lectures are free with Museum admission. For readers interested in learning more about Westerns, I asked Kevin to recommend one film for required viewing: "I would have to go with John Ford's The Searchers (1956). It has one of the greatest performances in a Western: John Wayne as the racist avenger Ethan Edwards. Set in Monument Valley, it is a film of great artistry and the color photography is spectacular. If you see it on the big screen, you feel as if you are out in the Old West."