Henry Merwin Shrady (American, 1871–1922). Buffalo, 1899 (cast ca. 1901). Bronze, 14 x 13 1/2 x 10 in. (35.6 x 34.3 x 25.4 cm). Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas (1999.21)

Nearly every turn-of-the-twentieth-century sculptor of western themes, whether an animal specialist or not, at some point modeled the bison, the largest North American mammal. Whether poised or active, static or frenetic, the bison appears as the principle subject in six sculptures in The American West in Bronze, 1850–1925. Also consider elements that served as shorthand for the transformation of the Old West and attendant squandering of natural resources—bison skulls on bases (see below, right) and the outline of a bison skull in Charles M. Russell's signature on his paintings and sculptures—and this animal, familiarly known as a buffalo, has a commanding presence in the exhibition.

Charles M. Russell (American, 1864–1926). Left: Buffalo Hunt, 1905 (cast 1905). Bronze, 10 x 19 x 12 3/4 in. (25.4 x 48.3 x 32.4 cm). Right: An Enemy that Warns, 1921 (cast ca. 1922–28). Bronze, 5 1/8 x 8 x 6 in. (13 x 20.3 x 15.2 cm). Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas (1961.82 and 1961.89)

Throughout the 1900s, the Plains Indian buffalo hunt provided rich fodder for artists, first with such painters as George Catlin and Carl Wimar, and later notably with Charles M. Russell who produced more than fifty paintings and sculptures on this theme alluding to a purer, bygone West. In a future post, Shannon Vittoria will explore this subject, fascinating in its aesthetic and iconographic complexity, in a conversation with Brian W. Dippie, Professor Emeritus of History, University of Victoria, British Columbia, and a contributor to the publication accompanying The American West in Bronze, 1850–1925. This week we will focus on how the sculptors Edward Kemeys, Henry Merwin Shrady, and Alexander Phimister Proctor brought very different personal experiences to modeling three bison statuettes that are on view in the exhibition.

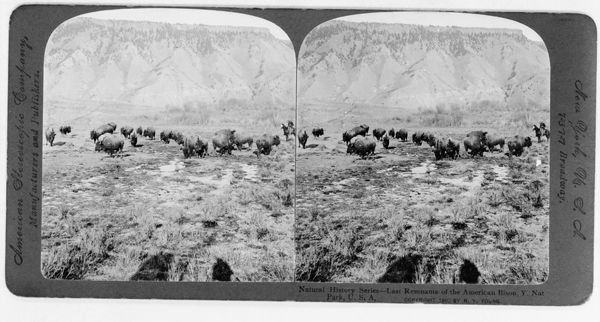

Last Remnants of the American Bison, Yellowstone National Park, U.S.A., ca. 1903. Photograph by American Stereoscopic Company. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

In the early nineteenth century, an estimated thirty million bison roamed the Great Plains, but by the mid-1880s, that number had been reduced to mere hundreds through both government-sanctioned hunting and environmental factors, an astonishing reduction of a species integral to American Indian lifeways—meat for food, bones for tools and weapons, hooves for glue, and hides for blankets, tipis, and clothing. Additionally, bison meat, tongues, and robes were traded with Euro-Americans in exchange for goods. During the 1870s and early 1880s, commercial hunters systematically slaughtered bison for hides, which were used to produce leather products. By the late 1880s, awareness of the species' near-extinction led to the opening salvos in the Conservation Movement. In 1894 the Yellowstone Game Protection Act to safeguard wildlife was enacted, the first law to protect bison. The Boone and Crockett Club, founded in 1887 by Theodore Roosevelt and George Bird Grinnell, promoted an ethic of purposeful hunting while advocating the protection of threatened species. Among the invitation-only band of sportsmen were artists Albert Bierstadt and Alexander Phimister Proctor; their fellow members proved to be effective and well-connected East Coast-based advocates who, among other efforts, brought about the establishment of the New York Zoological Society (the Bronx Zoo) in 1895. Later the American Bison Society, founded in 1905 by Roosevelt and William T. Hornaday through the auspices of the New York Zoological Society, was a leader in the species' regeneration. In 1907 it sent fifteen bison by train to the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Preserve in Oklahoma, the first in a series of successful repopulation efforts on western preserves.

Edward Kemeys (American, 1843–1907). Two views of Buffalo and Wolves, 1876 (cast probably 1878 or 1879). Bronze, 20 x 30 3/8 x 19 1/2 in. (50.8 x 77 x 49.5 cm). Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C., Gift of J. Willis Johnson (1984.141.2)

In 1873 Edward Kemeys, this country's first specialist in animal sculpture, traveled from New York as far west as Colorado and Wyoming, living among American Indians and trappers, and participating in bison-hunting expeditions. Kemeys studied the animals—alive and dead—through up-close examination, dissection, and sketching. Buffalo and Wolves was likely inspired by first-hand observation of an inter-species conflict in which a weakened or aged bison has been circled by four predatory wolves. The fate of hunters and hunted is still unresolved, though the bison is clearly doomed and two of the wolves appear gravely wounded. As is typical of Kemeys's sculptures, the surface is modeled loosely and expressively, with emphasis on behavioral narrative over anatomical exactitude.

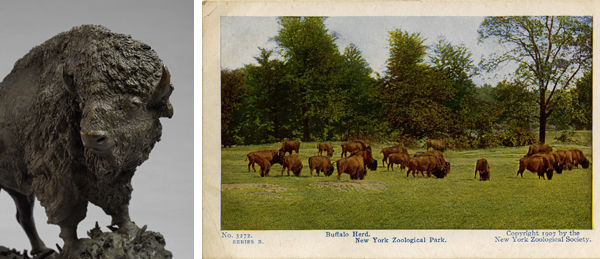

Left: Henry Merwin Shrady, detail of Buffalo. Right: New York Zoological Society, publisher, and American Colortype Co., printer. Buffalo Herd. New York Zoological Park, ca. 1907. Wildlife Conservation Society Archives, New York

Like Kemeys, Henry Merwin Shrady was essentially self-taught, but his knowledge of bison was based on trips to the Bronx Zoo rather than to the American West. It opened in 1899, with a herd of bison on view in a natural-habitat setting. Shrady, like other artists of his day, used the zoo as a reference tool of sorts (there was even an artists' studio in the Lion House) to complete on-the-spot sketches on their easels and modeling stands. With Buffalo, also known as Monarch of the Plains, Shrady expertly captures the animal's weighty bearing, its shedding coat a textural tour-de-force. He produced statuettes in two sizes, as well as enlarging a version to eight feet high in plaster to decorate the fairgrounds of the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, in 1901. Frederic Remington, a member of the American Bison Society, was so impressed by the quality and veracity of Shrady's Buffalo that he purchased a statuette for himself in 1908.

Alexander Phimister Proctor (American [born Canada], 1860–1950). Left: "For Q Street Bridge Washington D.C.," ca. 1911. Graphite on paper, 11 x 8 3/8 in. (27.9 x 21.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Gifford MacGregor Proctor, 1993 (1993.80). Right: Buffalo, 1912 (cast 1913 or after). Bronze, 13 1/2 x 19 x 9 3/4 in (34.3 x 48.3 x 24.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of George D. Pratt, 1935 (48.149.29).

Alexander Phimister Proctor was both a zoo animal observer and a western sportsman, an artist-naturalist whose sculptures were the result of broad experience. In 1911 he received a commission to produce four full-scale bronze bison for the Q (Dumbarton) Street Bridge in Washington, D.C. While traveling to western Canada in autumn 1911, Proctor visited Buffalo National Park near Wainwright, Alberta, a game preserve where he studied and sketched bison. Both the monumental bronzes and a sizable edition of statuettes truthfully record the wooly-maned bison in a stately pose. It remains to this day Proctor's most recognizable sculpture, no doubt due to the animal's lasting emblematic appeal.

Related Event

On Wednesday, March 19, at 6 p.m., Patrick Thomas, Vice President & General Curator, Wildlife Conservation Society, and Associate Director, Bronx Zoo, and I will co-present in the Met Salon Series program "The American Bison—Live and Sculpted." We will examine the impact and interconnectedness of artistic representations and conservation efforts involving this iconic animal.

This lecture is made possible by the Clara Lloyd-Smith Weber Fund.