John Martin (British, 1789–1854). Belshazzar's Feast, 1826. Mezzotint with etching. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, the Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1949 (49.40.262)

Prior to the nineteenth-century excavations of the major sites of Mesopotamia—cities such as Nineveh, Nimrud, and Babylon—the Bible was the West's primary reference point for information concerning the region. The echoes of the biblical Babylon can still be heard today, especially through one particular pop-culture reference: the science-fiction trilogy The Matrix. The three films depict a future in which human beings live in a simulated reality resembling modern-day New York, unaware that they are enslaved by sentient machines. Several individuals "wake up" and begin mounting a resistance, eventually led by the foretold savior, Neo.

The films include many examples of biblical image and allegory, particularly related to Babylon. The character Morpheus captains a hovercraft called the Nebuchadnezzar. A king of the Neo-Babylonian period, Nebuchadnezzar II reigned from 605 to 562 B.C. and was an active military campaigner, responsible for the sack of Jerusalem in 597 B.C. and the mass deportation of much of its citizenry (an event described in the Bible as the Babylonian Captivity).

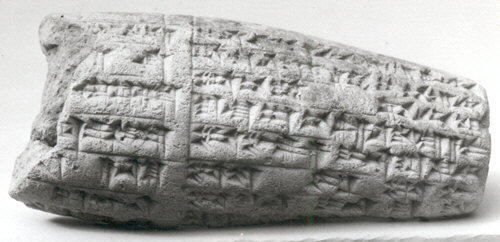

Cuneiform cylinder: inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II, ca. 604–562 B.C. Neo-Babylonian. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase 1886 (86.11.57)

Nebuchadnezzar is famous—or perhaps infamous—for how he is depicted in the Bible, particularly in the Book of Daniel, which describes events at the close of his reign. The references in the film are overt: just as Daniel interprets Nebuchadnezzar's dreams, the ship's captain is named Morpheus, after the Greek god of dreams. When the ship is destroyed in the second film, he quotes (or rather paraphrases) Daniel, saying: "I dreamed a dream . . . but now that dream is gone from me" (Daniel 2:3).

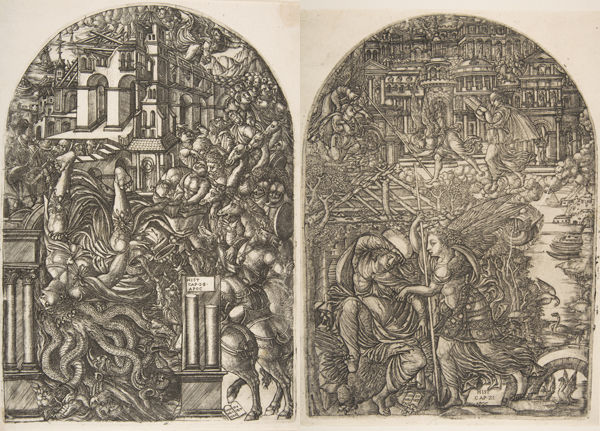

Subtler nods to the Bible appear elsewhere in the films, concealed within references to particular biblical verses. Agent Smith's license plate (seen in The Matrix: Reloaded) reads "IS 5416," referencing Isiah 54:16: "See, it is I who created the blacksmith who fans the coals into flame and forges a weapon fit for its work. And it is I who have created the destroyer to wreak havoc." A plaque aboard the Nebuchadnezzar reads "Mark III, No. 11," as a reference to Mark 3:11: "And whenever the unclean spirits saw him, they fell down before him and cried out, 'You are the son of God.'" Leaving aside the Neo-as-Messiah theme that permeates the entire trilogy, the idea of the fall, preservation, and final rise of humanity echoes throughout the films' use of the city of Zion as the last stronghold of human civilization. The image of Zion itself, in both the film and biblical sources, is tied strongly into the apocalyptic themes of the last book of the New Testament, the Book of Revelation, also known as the Apocalypse of John. This book has been a favored source for artists' woodcut illustrations, the most well known being by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), whose style was echoed by other artists, including Jean Duvet (ca. 1485–1561). Duvet illustrated two scenes from the Book of Revelation that highlight the importance of the idea of Zion, as well as the echoes of Babylon as a fallen city:

Jean Duvet (French, ca. 1485–after 1562). The Fall of Babylon (left) and The Angel Shows Saint John the New Jerusalem (right), from The Apocalypse. Engraving. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1925 (25.2.85 and 25.2.89)

In the first of these images, we see the destruction of Babylon, as in Revelations 18:2 "Fallen, fallen is Babylon the great! She has become a dwelling place of demons and a prison of every unclean spirit." Following this, we see the depiction of the new Jerusalem, in Revelations 21:2, "And I saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down out of Heaven from God, made ready as a bride adorned for her husband." Here, the new, heavenly Jerusalem is presaged by the appearance of a new Heaven and Earth—a renewed land after the destruction of the previous one. The Zion of The Matrix films, a subterranean city four kilometers beneath the Earth's surface, may seem a stark contrast to celestial glory, but the idea is similar: although the world in the Matrix has not renewed itself, the city of Zion stands as the new center for those who have not accepted the false world created by machines.

The Matrix is concerned with the power and integration of symbols and image, ideas that draw heavily from Simulacra and Simulation, a 1981 publication by French philosopher Jean Baudrillard. The book has a cameo role in the first film:

Clip from The Matrix (1999) showing a copy of Simulacra and Simulation, via YouTube.

Baudrillard articulated the relationship between an image and the reality it represented: "It is no longer a question of imitation, nor duplication, nor even parody. It is a question of substituting the signs of the real for the real" (Simulacra and Simulation, p. 2). In other words, the image of an object could be mistaken—or even preferred—over the object itself. The film directly addresses this through the character of Cipher, who chooses to leave the real world to once again experience the false pleasures of the Matrix, illusory as they are. The devastated wasteland of Zion exists as the place of civilization's survival and potential rebirth, while the false world of the Matrix resembles the height of decadence and power: a modern-day Babylon.

Anton Joseph von Prenner (Austrian, 1683–1761). The Tower of Babel. Etching. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Algernon S. Sullivan, 1919 (19.56.90)

The narrative of Babylon, as interpreted by the biblical sources, is one centered on its decadence and eventual, cataclysmic fall. Although we can contrast the biblical Babylon with its historical, Mesopotamian reality, the image of the fallen city remains—as illustrated by The Matrix—an enduring one.