Game box with chariot hunt, ca. 1250–1100 B.C. Enkomi, Cyprus. The Trustees of the British Museum

Board games were popular entertainments in the ancient Near East. So what games did the Assyrians and the Phoenicians like to play? Part of the answer is in the very first room of the exhibition Assyria to Iberia at the Dawn of the Classical Age, on an ivory box from Enkomi. This unique object has a grid with twenty playing squares incised on its upper surface. Although no accessories were found with this box, we can deduce from other archaeological assemblages and pictorial representations what kind of pieces and dice were required.

Double-sided game box with playing pieces and a pair of knucklebones. Thebes, Egypt. ca. 1635–1458 B.C. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1916 (16.10.475a). This work is on permanent display in Gallery 114.

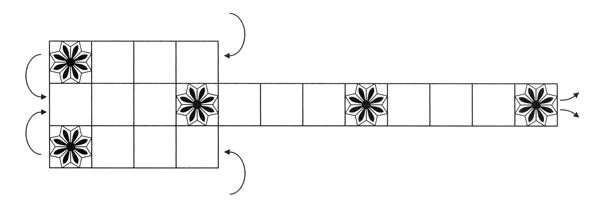

It is generally assumed that the two players started on each of the opposite sides of the board, as shown in the drawing below. They then moved their pieces down the central aisle toward the final field and off the board to win the game. Every fourth square is marked with a rosette or other symbol or inscription. These special squares seem to have functioned as lucky fields, be it that a piece was safe from being captured or that the player was given another throw. We know from liver-shaped game boards that divination was sometimes even performed on such surfaces. The use of dice—instruments of chance—placed the final outcome in the hands of Fate or Divine Will.

The game of twenty squares in the second and first millennia B.C. and the route of play. After I. Finkel, "On the Rules for the Royal Game of Ur," Ancient Board Games in Perspective, British Museum Press, 2007 (fig. 3.5)

Additional videos about rules and game play for twenty squares are available on the website of the Harvard Semitic Museum: http://semiticmuseum.fas.harvard.edu/games

The game box from Enkomi represents the westernmost example of the game of twenty squares. This game, distributed from Iran to the Levant, was certainly one of the most popular board games in the ancient Near East from the mid-third to the mid-first millennium B.C. It is also known as the Royal Game of Ur, since the famous Sumerian boards from Ur in southern Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) were early versions of this game.

Royal Game of Ur with gaming pieces and tetrahedrons, ca. 2600 B.C. The Trustees of the British Museum. This example was among the highlights of the exhibition Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus, organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2003.

Board games are found in many forms—from graffiti scratched on bricks to elaborately designed boxes—showing that they were popular with players of all social classes. Prestigious game boxes were among the luxury goods that circulated between the palatial societies of the Eastern Mediterranean. Most of the archaeological evidence of gaming material comes from funerary contexts, as grave offerings are often better preserved than other objects. Many games have vanished because their boards were made from perishable material, such as textile, leather, and wood, or simply drawn on the ground.

In Egypt and the Levant, grids for the game of twenty squares were combined with those for the famous Egyptian game of senet, meaning "passing," and strongly connected with the journey to the afterlife. The idea of having two games on the opposite sides of reversible boxes, with a drawer to keep the playing pieces and dice, is certainly one of the most brilliant in the history of board game design. It has been suggested that the box from Enkomi had a senet track on its underside, which had disintegrated by the time the box was excavated.

Ivory or bone games were still being produced in the early first millennium B.C. in the Levant. In fact, a complete playing surface with the special squares signaled by rosettes, like the Enkomi track, was recently discovered at Gezer in Israel.

Ivory game board, 10th–9th century B.C. Tel Gezer. Excavations co-directed by Steven Ortiz of the Tandy Institute for Archaeology and Samuel Wolff of the Israel Antiquities Authority. Photograph by Annie Wegman

No doubt, some of the ivory plaques discovered at Nimrud may have once adorned game boards. Thanks to stone examples, we know that board games such as the game of twenty squares and the game of fifty-eight holes were part of the entertainment at the Assyrian court. Moreover, rough tracks scratched on the base of stone sculptures revealed that the game of twenty squares was played by some guards on duty in Sargon's palace at Khorsabad, about 705 B.C.

Beautifully carved with a chariot hunt and animal scenes, the side panels of the Enkomi box illustrate a long tradition of decorated board games. Combat scenes and animals in confrontation are often depicted on gaming boxes as a metaphor for the contest between the players.

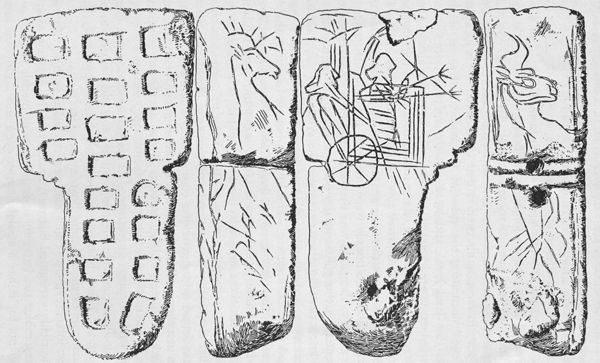

Chariot scene on the reverse of a game of twenty squares. Tell Halaf, Syria, early first millenium B.C. After D. van Buren, "A Gaming-board from Tall Halaf," Iraq 1, 1937 (fig. 1). This stone game board, was recently identified during the restoration project of the Tell Halaf Museum collection.

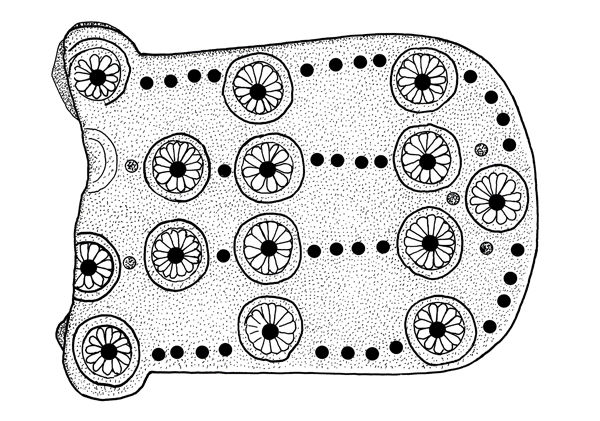

The rosette, a benevolent motif, is omnipresent in the ancient Near East, as is demonstrated in Assyria to Iberia at the Dawn of the Classical Age. It is the traditional emblem of Inanna/Ishtar, the most important female deity in ancient Mesopotamia, and occasionally replaced the star as her symbol in her astral aspect of the planet Venus (the morning and evening star). As goddess of war, Inanna/Ishtar was well suited to oversee the metaphoric battle of a game, so it makes sense that the rosette was an essential symbol on game boards as early as the third millennium B.C. In addition to being placed in special squares to indicate certain privileges, the rosettes are also featured on the outside of the playing surface, on the side of the board, or on its reverse.

Detail of the decorated side of a game of twenty squares, Balawat (Iraq). 9th–8th century B.C. Musée du Louvre. Photograph by Sarah Graff

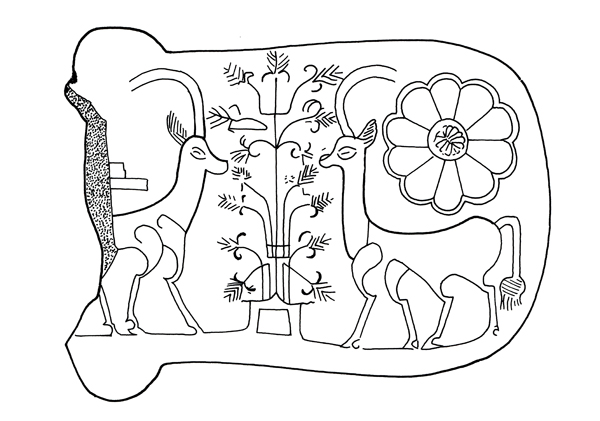

Drawing of a game of 58 holes and its reverse. Said to be from Luristan, early 1st millenium B.C. Musée du Louvre. Drawing by Caroline Florimont