Pieter Coecke van Aelst (Netherlandish, 1502–1550). Design for a nautilus cup with Neptune riding a Hippocampus, ca. 1535–40. Pen and brush and two shades of brown ink, blue and red watercolor over black chalk; 11 5/8 x 8 1/4 in. (29.5 x 21 cm). Princes of Waldburg-Wolfegg, Wolfegg Castle

Stijn Alsteens, curator in the Department of Drawings and Prints and a co-curator of Grand Design: Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Renaissance Tapestry, selected the exhibition's array of drawings. I recently spoke with Stijn about Coecke's highly accomplished, technically complex, and rare drawings.

Sarah Mallory: As a curator of drawings, how do you approach the work of Pieter Coecke van Aelst?

Stijn Alsteens: I think it is fair to say that drawings stand at the core of Coecke's oeuvre. They comprise the only substantial group of autograph works left by him. There do not seem to be all that many paintings which he made himself, and of course he did not weave the tapestries, nor did he himself produce the prints, stained-glass windows, or other works for which he provided designs. So, it is the drawings that I think bring us closest to who Coecke was as an artist and which give us the clearest understanding of his stylistic development and mastery. My research in preparation for the exhibition allowed me to work not only on the sheets selected for the show, but also on a complete catalogue of Coecke's drawings, which I was fortunate to be able to publish in the scholarly journal Master Drawings.

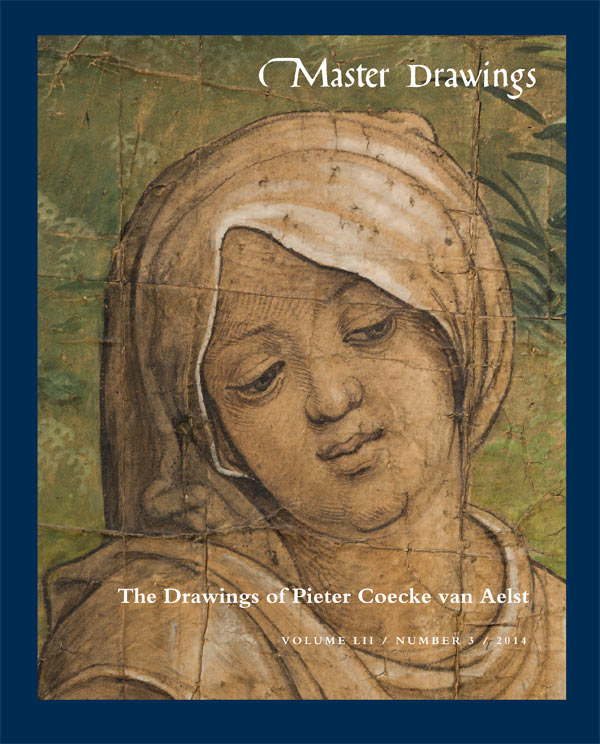

Cover of Master Drawings featuring a detail from The Martyrdom of Saint Paul cartoon for a tapestry in a set of the Story of Saint Paul. Pieter Coecke van Aelst and workshop, ca. 1535. Brush in brown ink with distemper, over black chalk; 11 ft. 2 5/8 in. x 12 ft. 7 1/8 in. (342 x 384 cm). Museum of the City of Brussels

Sarah Mallory: How many drawings comprise Coecke's oeuvre?

Stijn Alsteens: Though, as I said, Coecke's drawings are the only substantial body of autograph works left by him, they are still fairly rare. I accept about forty drawings as autograph, in addition to cartoons and cartoon fragments on which he must have worked with assistants, and some drawings that I believe are workshop copies after drawings by Coecke. That is still a very small oeuvre compared to the hundreds of drawings that often survive by contemporary Italian, especially Tuscan, artists, and by some German draftsmen like Albrecht Dürer. Obviously, the forty or so drawings I recognize as Coecke's must be a fraction of his actual output.

Sarah Mallory: Why do so few of Coecke's drawings survive?

Stijn Alsteens: Netherlandish drawings from the first half of the sixteenth century in general do not survive in great numbers. It may have to do with the damage of time—fire, war, humidity—but it may also say something about the local appreciation for these artists and for their drawings. Probably in Italy, or for an artist like Dürer, there was a greater appreciation already at the time for drawings, which must have contributed to the preservation of more pieces over the course of the centuries.

Sarah Mallory: How and why did you select the drawings included in the Grand Design exhibition?

Stijn Alsteens: In selecting from Coecke's extant drawings, I wanted to give as complete an impression of his designs for tapestries, while also including some examples of designs for works in other media. The majority of Coecke's drawings are related to tapestries, and we were able to reunite all the drawings that survive for the Saint Paul series, as well as nearly all the autograph drawings related to other tapestry series by Coecke. Some of them have never before featured in exhibitions outside the institutions where they are kept, such as the Saint Paul Directing the Burning of the Heathen Books preparatory drawing for the tapestry in the Life of Saint Paul series, now in the collection of the Universiteitsbibliotheek in Ghent.

Pieter Coecke van Aelst (Netherlandish, 1502–1550). Saint Paul Directing the Burning of the Heathen Books preparatory drawing for the tapestry in a set of the Story of Saint Paul, ca. 1529–30 or 1535. Pen and brown ink, brush and brown ink, heightened with white gouache; 10 1/4 x 17 3/4 in. (25.9 x 45 cm). Universiteitsbibliotheek, Ghent (TEK 3504)

Sarah Mallory: Can you tell us a little bit about Coecke's approach to design, as exemplified by his drawings?

Stijn Alsteens: An important aspect of Coecke's art in general and of his drawings in particular is his awareness of what is happening in Italy and his ambition to emulate that. Already in the later 1520s, he manages to marry his Northern training with his excitement and appreciation for Italian art. Under Italian influence, his figures gain much greater monumentality, and movement and drama become much more important. His main model appears to have been Raphael and the artists from his circle. He must have known some of their compositions and works already, but around 1533, when Coecke made a trip to Constantinople, he appears to have also visited Mantua, where Giulio Romano, Raphael's star pupil, worked at the time.

After Raphael's death in 1520, Giulio had brought a lot of drawings by Raphael and his school with him to Mantua. There, Coecke must have been able to truly immerse himself in Italian art, and although other Netherlandish artists preceded him in going to Italy, I think Coecke is the one who for the first time fully internalized the lessons Northerners could draw from Italian art. For instance, his understanding of human anatomy is much greater than that of any of his Netherlandish predecessors. After his return from Constantinople and Italy, we see that Coecke's style has changed. Some of his later drawings, such as the Fall of the Giants drawing in the collection of the Rijksmuseum, could almost be mistaken as Italian in terms of composition and technique. Another aspect that really distinguishes Coecke from many other artists is the technical refinement and complexity of his drawings, which go far beyond what is necessary. I think he enjoyed making the drawings as attractive as he could. As someone with a special interest in drawings, I of course very much appreciate that effort.

Pieter Coecke van Aelst (Netherlandish, 1502–1550). Fall of the Giants drawing, ca. 1540–44. Pen and two different shades of brown and gray ink, brush and brown ink, and white gouache, over black chalk; 10 7/8 x 16 1/8 in. (27.5 x 40.9 cm). Rijksprentenkabinet, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (RP-T-1951-253)

Sarah Mallory: What do you mean by "technical refinement and complexity"?

Stijn Alsteens: Most of Coecke's contemporaries, such as the painter and tapestry designer Bernard van Orley, with whom Coecke must have worked in the 1520s, used a basic technique consisting of pen, with washes, colored or not, for modeling. Coecke also uses this simple technique in the early stages of developing a composition, but when he has to make a more detailed drawing, he uses a much wider variety of techniques: pen, but also point of brush, subtle washes, and bolder ones. He uses white gouache, but also the natural color of the paper as reserve, which contrasts with large toned areas. Once the composition is mostly complete, he sometimes goes over the drawing again with a fine pen and darker ink. A good example is Saint Paul Preaching to the Women of Philippi, the final design for a tapestry in the Life of Saint Paul series from the collection of the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung in Munich.

Pieter Coecke van Aelst (Netherlandish, 1502–1550). Saint Paul Preaching to the Women of Philippi petit patron for the tapestry in a set of the Story of Saint Paul, ca. 1529–30. Pen and brown ink, brush and brown ink, heightened with white; 10 x 19 in. (25.3 x 48.4 cm). Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich (1927:79 z)

Sarah Mallory: What is the relationship between Coecke's drawings and his tapestry cartoons? His drawings and his tapestries?

Stijn Alsteens: For the Saint Paul series, we really are fortunate to have drawings from the very different stages of the tapestry design process. In the exhibition we have relatively small, sketchy drawings that represent the early stages of the development of the composition, then the petits patrons, which are the finished designs for a tapestry, and then fragments from the full-scale cartoons, which can be compared directly to the tapestries. What we were all struck by while working on the exhibition was how closely Coecke appears to have remained involved in the production of the cartoons. To us, the quality of Coecke's tapestry cartoons, which carefully prepare the effects found in the tapestries, indicate he was very much aware of the possibilities of the woven medium and wanted to be in control of the final result as much as possible.

Sarah Mallory: What is your favorite work by Coecke in the exhibition?

Stijn Alsteens: When you have lived with a great artist's work for some time, that's a difficult question. Of the drawings, I think the high point of Coecke as a draftsman lies somewhere in the mid-1530s, and I find the Louvre's Joshua Praying before the Ark after the Defeat at Ai, a preparatory drawing for a tapestry in the Story of Joshua series, particularly beautiful. The tapestries are of course splendid, but among the finished works, I also greatly admire the woodcut frieze of the Customs and Fashions of the Turks because of the intricacy of the compositions, and the rich detail and sympathy with which its subject is represented. To me, it is one of the masterpieces of sixteenth-century Netherlandish art.

Pieter Coecke van Aelst (Netherlandish, 1502–1550). Joshua Praying before the Ark after the Defeat at Ai preparatory drawing for the tapestry in a set of the Story of Joshua, ca. 1535–37. Pen and brown ink, brush and gray ink, over black chalk, on light brown-gray paper, squared for transfer in black chalk (laid down); 10 5/8 × 15 3/8 in. (27 x 39.1 cm). Musée du Louvre, Paris (19204)

Sarah Mallory: Did you have any new insights about Coecke as a result of the research you did for this exhibition?

Stijn Alsteens: In the past, Coecke's work as a painter and draftsman had been described in a very inclusive way. Maryan Ainsworth, our curator of Netherlandish paintings, and I felt many works previously associated with Coecke had to be rejected, and by pruning, I think we arrived at a more precise definition of his style and development as an artist. Fortunately, we were also able to add a few important works, such as the design for a nautilus cup in the German princely collection at Wolfegg Castle, where it was previously attributed to an artist from the circle of Hans Holbein the Younger.

For me in particular, studying the drawings made it possible to come closer to an artist who seems to have seen himself in the first place as a designer, who determined in considerable detail the appearance of the final work of without always creating it with his own hands. One of the great joys of working in an institution like the Metropolitan is to be able to work closely with experts in other media and develop an exhibition and catalogue like we did for Coecke. If this had been just a show of tapestries or paintings or drawings, it would have been much less interesting, and, frankly, a show that would hardly have been worth doing. Only by bringing everything together were we able to do justice to Coecke's genius, and to share the incredible diversity and great beauty of his work with the public.

View from Grand Design's second gallery of the petit patron and tapestry cartoon fragment for the Conversion of Saul tapestry in a set of the Story of Saint Paul. Designed by Pieter Coecke van Aelst, ca. 1529–30. Probably woven under the direction of Frans van den Bossche, Brussels, before 1563. Wool, silk, and silver- and silver-gilt-metal-wrapped threads. Tapestry on loan from the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich (T 3844.1)